the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

From river mouth to reef: benthic foraminifera assemblages reveal ecological dynamics in a mixed carbonate–siliciclastic Brazilian continental shelf

André R. Rodrigues

Fabiana K. de Almeida

Valéria S. Quaresma

Renata M. de Mello

Caroline F. Grilo

Kerly A. Jardim

Priscilla P. Romualdo

Alex C. Bastos

The recent benthic foraminiferal assemblages have been considered to be a very useful tool as analogues for understanding environmental changes in the past oceans. In order to identify distribution patterns, the benthic foraminiferal assemblages (total fauna, >63 µm), along with sedimentological data, have been investigated on the continental shelf of the Espírito Santo Basin (ESB, between 18°20′ and 21°20′ S). The ESB is distinguished from the other Brazilian basins due its geomorphologically diverse continental shelf and slope; this is apart from it being economically important for oil exploration. Seafloor samples (0–2 cm) from 18 to 150 m were distributed in seven transects arranged perpendicularly to the coast. The density, taxonomic diversity, and assemblage of the total biota composition have changed significantly along the Espírito Santo continental shelf (ESCS). This study identified five main benthic foraminiferal assemblages along the ESCS, each associated with distinct sedimentary and environmental characteristics. The cluster analysis reveals five groups which were named after the abbreviation of the main species or genera. Group M–C is characterized by the marked presence of Miliamina subrotunda and Cibicides spp., as well as by high values of diversity and richness, indicating a stable environment. Group H–Q is dominated by Hanzawaia boueana and Quinqueloculina spp. in areas with terrigenous sediments and biogenic carbonate deposits. Group G–T is associated with high organic matter content and a marked presence of Globocassidulina rossensis and Trifarina angulosa. Group Q–B is linked to high-energy environments with bioclastic sediments and is dominated by Quinqueloculina cuvieriana and Bigenerina textularioidea. Group A–P is found on the Abrolhos Shelf, characterized by high abundances of porcelaneous symbiotic foraminifera, such as Articulina sulcata and Peneroplis planatus, in carbonate sediments. The distribution of these assemblages is primarily controlled by sediment composition, grain size, organic matter flux, and hydrodynamic conditions. Sediments rich in carbonate seem to favor symbiotic-bearing foraminifera species adapted to oligotrophic environments, while regions with higher organic matter content support opportunistic and infaunal species. The results highlight the interplay between sedimentary and oceanographic processes and ecological factors in structuring benthic foraminiferal assemblages along the ESCS.

- Article

(7834 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(493 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Several studies have explored the relationship between foraminiferal distributions and environmental drivers such as riverine chemical and sediment inputs and distinct oceanographic forcings (tides, waves, and currents) (e.g., Debenay et al., 2001; Majewski et al., 2023; Fouet et al., 2024; Jorissen et al., 2022; Castelo et al., 2022). The abundance and diversity of benthic foraminiferal communities are closely tied to sediment grain size, organic matter input, and oxygen concentration in the marine sediments, reflecting seafloor hydrodynamics (Murray, 2006; Jorissen et al., 2007; Hyams-Kaphzan et al., 2008). These factors influence species composition, vertical distribution in sediments, and overall community structure, making benthic foraminifera valuable proxies for both past (Murray, 2006; Díaz et al., 2014; Mello et al., 2017; Rodrigues et al., 2018) and current environmental changes, including anthropogenic impacts (Culver and Buzas, 1995; Cearreta et al., 2002; Geslin et al., 2002; McGann et al., 2025). Furthermore, modern foraminiferal distributions play a fundamental role in determining assemblage composition and inferring paleoecological, paleobathymetric, and paleoceanographic conditions using modern analogs (Gooday, 1993; Sen Gupta, 1999; Hayward et al., 2004; Ruschi et al., 2024).

The distribution patterns of benthic foraminifera along the Brazilian continental shelf have been thoroughly documented in several key regions, notably in proximity to major coastal economic centers, including the margins of major metropolitan areas such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (Eichler et al., 2003; Donnici et al., 2012; Díaz et al., 2014; Eichler et al., 2014), on the Amazon shelf (Vilela, 2003) and in northeastern Brazil on the carbonate shelf (Araújo and Machado, 2008; Eichler et al., 2024; Barbosa et al., 2025). However, certain areas remain unknown, requiring further investigation to identify recent assemblages and to refine our understanding of these organisms along the western South Atlantic continental shelf.

The Espírito Santo Continental Shelf (ESCS) exhibits a complex sedimentary and morphological characteristic due to its mixed sediment composition, width variability, and riverine sediment input. The shelf is characterized by areas with siliciclastic sedimentation and areas dominated by carbonate sedimentation, with rhodolith beds throughout the entire outer shelf (Bastos et al., 2015; D'Agostini et al., 2019; Bourguignon et al., 2018; Vieira et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2020). The Doce River delta plays a significant environmental role in the sedimentary and ecological dynamics of the Espírito Santo shelf (Quaresma et al., 2015; Leite et al., 2016; Aguiar et al., 2023). In light of this complexity, the distribution of benthic foraminifera may be indicative of a gradient between environments characterized by distinct sedimentary regimes. This observation emphasizes the necessity for detailed mapping to support climate and oceanographic studies related to continental margin changes and potential anthropogenic impacts.

The present study aims to investigate the distribution of recent benthic foraminifera assemblages along the ESCS and to infer the predominant environmental factors that control their microfauna distribution. This study area covers a region later impacted by the 2015 Fundão Dam collapse (the world's largest mining disaster), which released over 60×106 m3 of iron-rich tailings into the Doce River basin, affecting over 600 km of terrestrial, freshwater, and estuarine ecosystems (Queiroz et al., 2022). Furthermore, this study endeavors to verify if the benthic foraminifera assemblages are in some way related to the three distinct morphologic compartments previously established in the ESCS (Bastos et al., 2015; Vieira et al., 2019) and if they are thereby related to different sedimentary regimes and their potential use to monitor human activity in the coastal environment.

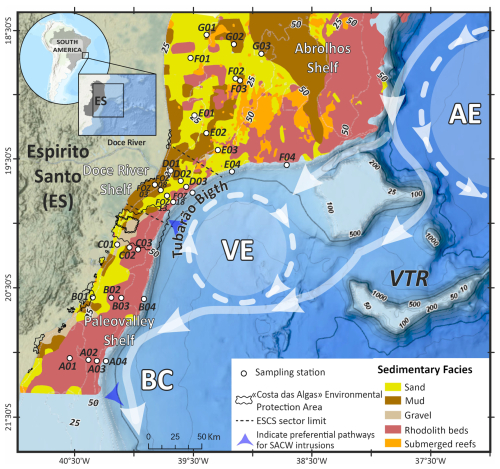

The ESCS, located along the eastern Brazilian margin between the latitudes of 18°20′ and 21°18′ S, is characterized by three sedimentary facies: terrigenous, mixed, and carbonate (Costa Júnior et al., 2022). The ESCS can be divided into three sectors based on sedimentary and morphological characteristics (Fig. 1): the Paleovalley, the Doce River, and the Abrolhos Continental Shelf (Bastos et al., 2015). Each sector exhibits distinct sedimentary regimes, morphology, oceanographic influences, and ecological dynamics, which are crucial for understanding the distribution of benthic foraminifera.

Figure 1Sedimentary facies distribution along the ESCS obtained from Bastos et al. (2015) and Vieira et al. (2019). Schematic surface circulation of the Brazil Current (BC), the Abrolhos Eddy (AE), and the Vitíoria Eddy (VE) is based on de Almeida et al. (2022) and samples distributed over the ESCS (transects A to G). The areas of SACW intrusion into the ESCS were based on Palóczy et al. (2016).

2.1 Paleovalley Continental Shelf

The Paleovalley Continental Shelf (south of the study area) is characterized by an accommodation regime, presenting an irregular morphology marked by paleovalleys and hard grounds and the presence of estuaries (Bastos et al., 2015; Vieira et al., 2019). This region is predominantly composed of carbonate sediments and topographic formations shaped during periods of seafloor exposure (Ximenes Neto et al., 2024). The presence of rhodolith beds and bioconstructions along paleochannel margins further highlights the unique sedimentary and ecological features of this sector (Oliveira et al., 2020).

2.1.1 Environmental protection area

The multiple-use “Costa das Algas” Environmental Protection Area (EPA) and the no-take Santa Cruz Wildlife Refuge (WR) are adjacent and form part of UNESCO's Mata Atlântica Biosphere Reserve. Established in 2010 by Brazil's Federal Government, these marine protected areas aim to protect marine biodiversity and local culture. They marked important milestones in safeguarding rhodolith beds from large-scale exploitation for fertilizer production by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA, 2006). Both areas hold great ecological and socioeconomic significance and safeguard vital habitats that protect the coastal zone from erosion and support the sustainability of artisanal fisheries, which is a key economic activity in the region (ICMBio, 2023).

2.2 Doce River Continental Shelf

The Doce River Continental Shelf, located in the central-northern ESCS, is driven by a high input of terrigenous sediments from the Doce River, with an estimated discharge of approximately 148 t km−2 yr−1 (Souza and Knoppers, 2003). This sector exhibits a smooth seafloor, corresponding to the delta front and prodelta of the Doce River delta (Bastos et al., 2015; Quaresma et al., 2015). The dominance of terrigenous sediments in this region reflects the direct influence of the Doce River as the primary source of sedimentary material. The deltaic environment is marked by modern sediments, with deposition extending to depths of approximately 30 m (Quaresma et al., 2015).

2.3 Abrolhos Continental Shelf

At the northernmost extent of the ESCS, the southern Abrolhos Continental Shelf represents a broadening of the eastern Brazilian Continental Shelf. This sector is characterized by a mixed siliciclastic–carbonate depositional system, with terrigenous sediments dominating the inner continental shelf and carbonate sedimentation prevailing offshore (Bastos et al., 2015; Vieira et al., 2019). The presence of isolated biogenic reefs, extensive rhodolith beds, and a broader continental shelf distinguishes this region from the other sectors. The transition from terrigenous to carbonate sediments is gradual, reflecting the interplay between terrigenous input and marine processes.

2.4 Oceanographic influences

The present-day ESCS is influenced by intricate interactions between large-scale circulation, mesoscale eddies, and local wind forcing. The Brazil Current (BC), formed by the bifurcation of the South Equatorial Current (SEC) near 18.6° S, exerts a strong influence on shelf dynamics, particularly to the south of the Vitória–Trindade Ridge (VTR). Mesoscale features, such as the Vitória Eddy and semi-permanent anticyclones, are frequently observed in this area (Soutelino et al., 2011; Arruda et al., 2013; Palóczy et al., 2016; Silveira et al., 2020).

Although the warm and saline Tropical Water (TW) is the dominant water mass along the shelf throughout the year, the South Atlantic Central Water (SACW), which is colder and fresher, sporadically intrudes near the bottom, especially during summer when a strong thermocline develops (Castro and Miranda, 1998). These episodic intrusions of nutrient-rich SACW have been identified as one of the triggers responsible for surface water nutrient enrichment, thereby influencing benthic assemblages (Bernardino et al., 2016; de Almeida et al., 2022, 2023).

Wind forcing drives southwestward currents along the shelf, with coastal upwelling being intensified by internal tides near the southern Abrolhos Bank (AB) (Pereira et al., 2005). Numerical studies suggest that, in the Tubarão Bight (TB), wind-driven Ekman transport dominates over topographic effects, accounting for over 75 % of vertical transport (Rodrigues and Lorenzzetti, 2001; Mazzini and Barth, 2013).

3.1 Sample collection

Surface sediment samples were collected during the development of the Espirito Santo Basin Assessment Project (AMBES, CENPES/PETROBRAS), which systematically sampled the Espirito Santo Basin (ESB) and the northern Campos Basin (NCB) between 2008 and 2014. We analyzed 30 sediment samples (0–2 cm), collected with a Van-Veen (stations shallower than 100 m) and box corer (stations deeper than 100 m) during an oceanographic cruise in 2013. Samples were stored in a plastic container (∼20 cm3). As the samples were not stained with Bengal Rose after the collection, the dataset counts are based on total fauna, giving a larger-scale time picture, avoiding seasonal variations in the foraminifera population. It is also known that the utilization of total fauna may be indicative of a mixture of autochthonous and allochthonous foraminifera (Hayward et al., 2004). Therefore, our data represent the overall faunal composition and distribution at ESCS. The samples were evenly distributed across seven transects on the shelf at water depths of 25, 40, 50, and 150 m and one transect at water depths from 18 to 50 m on the Doce River mouth (Fig. 1). The position of the stations can be accessed in the Supplement (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17313920).

3.2 Sedimentological data

The sedimentological dataset used in this study is a compilation of data analyzed and published by Maia et al. (2015) in the AMBES project report. The data encompass grain size, calcium carbonate (% CaCO3), and organic matter (% OM) content. As those authors' analyses were carried out in replicates, we opted to use the median values for each parameter. The gravel and sand fractions were analyzed via standard wet-sieving methods, while mud fractions were assessed through pipetting (Suguio, 1973; Dias, 2004). The % CaCO3 was determined by measuring the calcium carbonate loss through dissolution in 10 % HCl using a modified Bernard Calcimeter (Soares, 2017). The % OM was determined post-combustion at 450 °C by measuring the difference between dry weight and ash-free dry weight.

3.3 Total foraminiferal analysis

Sediment samples for foraminiferal analysis were processed at CENPES/PETROBRAS laboratory (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). After drying the samples at 60 °C, an aliquot of dry sediment for each sample (∼20 g) was gently washed with tap water through a 63 µm sieve to remove the mud fraction. The coarse fraction retained on the sieve was dried, weighed, and dry-sieved using 500, 125, and 63 µm to facilitate the species classification in the distinct grain sizes.

All benthic foraminifera specimens were picked from the 500 µm fraction. The fractions of 63–125 and 125–500 µm were divided using a microsplitter to ensure the presence of at least 300 specimens of benthic specimens for both fractions together. All picked specimens were placed on plummer slides for taxonomic identification. The total absolute number of foraminifera for each sample was standardized to 20 g.

The tubular agglutinated forms, including genera such as Rhabdammina, Rhizammina, and Saccorhiza, were quantified based on the presence of standardized fragments. Every set of five fragments (approximately 0.3 cm in length) was counted as one single individual, following de Almeida et al. (2022, 2023). Juvenile forms were identified when the specimens had a large proloculum and a whole small test (125–63 µm fraction) without enough features to be identified to the species level. Due to their large number of species and ecological similarity, members of the genera Fissurina, Lagena, Oolina, and Parafissurina (Nodosariata) were grouped and nominated to be “unilocular”, according to Patterson and Richardson (1987).

Taxonomic classification and identification were conducted following Boltovskoy et al. (1980), Loeblich and Tappan (1988, 1994), Boersma (1984), van Morkhoven et al. (1986), Bolli et al. (1994), Jones (1994), Kaminski and Gradstein (2005), and Holbourn et al. (2013). The species names were updated according to the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS Editorial Board, 2022). The main species (up to 140) were compared with the holotypes and syntypes of the Cushman Foraminifera and other collections held at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Smithsonian Institute (USA). All figured specimens are reposited in the Laboratory of Marine Geosciences (LaboGeo) collection at the Department of Oceanography and Ecology at the Universidade Federal do Espirito Santo (Brazil).

In addition to benthic taxa, planktic foraminiferal tests were also recorded during the picking process using the >125 µm size fraction. This fraction was selected based on its ability to capture the majority of adult planktic species (Peeters et al., 1999; Tapia et al., 2022).

3.4 Statistical analysis

The benthic foraminifera density (density = number of tests dry sediment gram) was calculated for each sample, as well as the percentage of agglutinated tests (% AGGLU) representing the subclass Textulariana (class Globothalamea) and the class Monothalamea, porcelaneous forams (% PORC) that represent the class Tubothalamea, and calcareous hyaline forams (% HYAL) that represents the subclass Rotaliana (class Globothalamea) and the class Nodosariata (Pawlowski et al., 2013).

The microhabitat preference (epifaunal vs. infaunal) was differentiated based on the morphotypes of the tests as proposed by Corliss (1985), Corliss and Chen (1988), Kaminski et al. (1995), and Murray (2006). Species diversity is expressed in terms of species richness (S), equitability (J), and Shannon–Wiener (H) and Fisher's α indexes (Magurran, 2004). The calculations of these indexes were performed using PAST 4.10 software (Hammer et al., 2001).

The relative abundance of all taxa identified was analyzed through Q-mode cluster analysis in order to help define foraminiferal assemblages. The Bray–Curtis distance was used to measure the proximity between samples, and Ward's method was used to arrange samples into a hierarchical dendrogram.

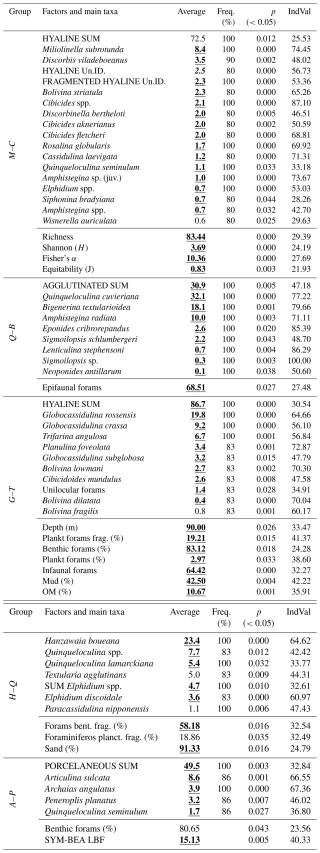

The Indicator Species Analysis (IndVal) (Dufrene and Legendre, 1997) was used to determine exactly which parameters (species and environmental factors) were unique to each group, with important differences in community assemblage. The IndVal was determined by first calculating the relative abundance and relative frequency of each foraminifera species within each group formed through the Q-mode cluster. Those scores were then multiplied to yield the final indicator value. The statistical significances (p values) of the indicator values are estimated by means of 9999 random reassignments (permutations) of sites across groups. The resulting p value represents the probability that the calculated indicator value for any species or factor was bigger than that found by chance (Table 1).

Table 1Example of how the IndVal data are expressed.

1 Factors and main taxa: the species or taxa, ecological indices, or environmental variables (e.g., sediment type, organic matter content) being evaluated for specific groups. 2 Average: the mean relative abundance of the species (or the value of another parameter) within a given group. 3 Freq. (%): the frequency of occurrence (%) of the factor across sites within the group. A frequency of > 80 % is often used as a threshold to identify reliable indicators. 4 p (<0.05): the p value obtained from permutation tests. Values below 0.05 indicate that the factor is significantly associated with the group. 5 IndVal: the Indicator Value, ranging from 0 to 100. It reaches its maximum (100 %) when the factor occurs at all sites of only one group. Some factors (e.g., foraminiferal density, sand, or mud content) may be evenly distributed across sites, but differences in mean values can still result in significant indicator values.

The analyses were performed using software packages PAST 4.10c (Hammer et al., 2001), PRIMER v.5 (Clarke and Warwick, 1994), and STATISTICA v.7 (Statsoft, 2001).

4.1 Sediment properties: grain size, calcium carbonate, and total organic matter content

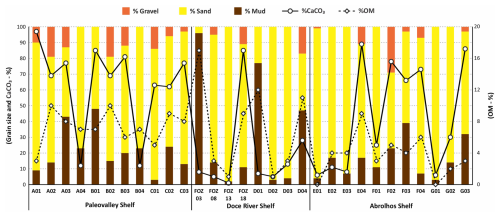

The sedimentological results are presented in the Supplement (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17313920) and Fig. 2. In general, sediments from the ESCS are predominantly composed of carbonate sand and mud. According to Larsonneur's (1977) classification, sediments from the ESCS include terrigenous (<30 % CaCO3), mixed (30 %–75 % CaCO3), and carbonate (>75 % CaCO3) facies. Terrigenous sediments were mainly observed in FOZ03, FOZ13, and D02 (16 to 41 m water depth). In these samples, the CaCO3 content reflected a larger siliciclastic influence near to the Doce River mouth. Mixed sediments dominated across the continental shelf, while carbonate sediments were identified in A01, B01, and FOZ18, indicating carbonate-rich environments.

Figure 2Sedimentological data (gravel, sand, mud, calcium carbonate, and total organic matter content) on the ESCS. Values expressed in percentages.

The highest mud content was observed at the Doce River mouth region (FOZ03 and D01), where terrigenous mud dominates, as well as in B01 and D04. In contrast, sandy sediments with minimal mud fractions (<5 %) were recorded in C01, FOZ13, and G01. Furthermore, high gravel content (>10 %) was predominantly present in FOZ18, F02, and E04.

The organic OM content exhibited a range from 1 % to 17 %, with elevated values typically correlating with fine-grained sediments. The highest OM content was recorded in FOZ03, D01, and D04, consistently with the predominance of muddy deposits, while the lowest values (<2 %) were found in FOZ13 and D02.

4.2 Benthic foraminiferal composition: density, diversity, and relative abundance

A total of 274 benthic foraminiferal taxa were identified, comprising 237 species and 154 genera in the analyzed samples (see the Supplement – https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17313920).

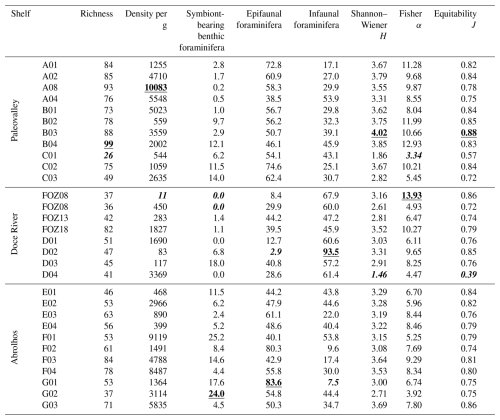

The total benthic density ranges from 11 to 10 083 tests per gram, with high values on transects A and B on the Paleovalley Shelf and on transects F and G on the Abrolhos Shelf. The species richness ranged from 26 to 99 species per sample, with the highest values being observed at transects A and B on the Paleovalley Shelf and at transect F on the Abrolhos Shelf. The Shannon–Wiener index (H) varied between 1.46 and 4.02, with elevated values at transects A, B, and G (B03: 4.02, G03: 3.69), indicating high species diversity in these areas. The Fisher α index, which reflects species richness relative to sample size, ranged from 3.34 to 13.93, with the highest values at transects B and FOZ. Equitability (J) values ranged from 0.39 to 0.88, demonstrating a generally well-distributed species community, particularly at transects B and G.

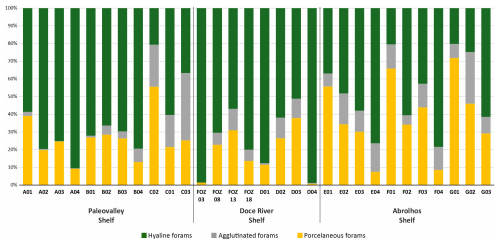

The distribution of hyaline, porcelaneous, and agglutinated foraminifera across the study area revealed distinct patterns (Fig. 3). The calcareous hyaline taxa dominated most of the transects (ranging from 20.2 % to 98.6 %), and were particularly dominant in the FOZ03 (98.6 %) and D01 (98.9 %). In contrast, porcelaneous taxa exhibited low abundances values (ranging from 0.8 % to 71.8 %), with the highest values being observed at G01 (71.8 %) and F01 (65.9 %). Agglutinated taxa were generally less abundant (ranging from 0 % to 38.1 %), with the highest values being recorded at C03 (38.1 %) and E01 (17.5 %).

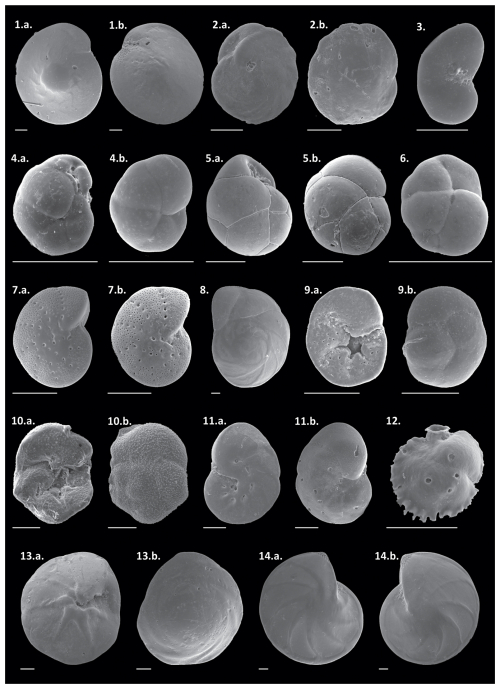

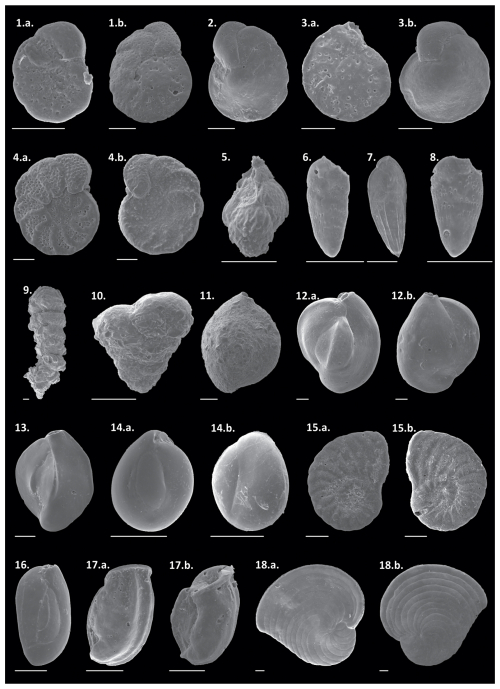

The relative abundances of all species can be observed in the Supplement (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17313920), and those of the main species in Plates 1 and 2. The dominant taxa include the hyaline species Globocassidulina rossensis, with an average abundance of 8.4 %, and Hanzawaia boueana, with an average abundance of 7.8 %. Hyaline juvenile foraminifera were frequently abundant (average of 4.4 %). Additionally, the porcelaneous species Quinqueloculina cuvieriana and Quinqueloculina lamarckiana were also abundant (>3 %) and frequently observed. Among the agglutinated species, Bigenerina textularioidea is the most abundant and frequent, with an average abundance of 3.36 %.

Plate 11. a.–b. Amphistegina radiata, 2. a.–b. Cassidulina laevigata, 3. Paracassidulina nipponensis, 4. a.–b. Globocassidulina crassa, 5. a.–b. Globocassidulina subglobosa, 6. Globocassidulina rossensis, 7. a.–b. Elphidium discoidale, 8. Eponides cribrorepanus, 9. a.–b. Discorbis viladeboeanus, 10. a.–b. Rosalina globularis, 11. a.–b. Hanzawaia boueana, 12. Siphonina bradyiana, 13. a.–b. Neoponides antillarum, and 14. a.–b. Lenticulina stephensoni. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Plate 21. a.–b. Cibicides aknerianus, 2. Cibicidoides mundulus, 3. a.–b Cibicides fletcheri, 4. a.–b. Planulina foveolata, 5. Trifarina angulosa, 6. Bolivina dilatata, 7. Bolivina fragilis, 8. Bolivina lowmani, 9. Bigenerina textularioidea, 10. Textularia agglutinans, 11. Sigmoilopsis schlumbergeri, 12. a.–b. Quinqueloculina cuvieriana, 13. Quinqueloculina lamarckiana, 14. a.–b. Miliolinella subrotunda, 15. a.–b. Peneroplis planatus, 16. Quinqueloculina seminulum, 17. a.–b. Articulina sulcata, and 18. a.–b. Archaias angulatus. Scale bar: 100 µm.

The presence of symbiont-bearing benthic foraminifera exhibited significant variability across the study area, as indicated by the occurrence of the genera Amphistegina, Peneroplis, and Archaias. The total relative abundance of these genera ranged from 0 % to 25 %, with the highest values observed along transect F on the Abrolhos Shelf. High relative abundances of these species were also recorded along transects B and C on the Paleovalley Shelf (C03: 14.0 %, B04: 12.1 %) and on the transect E on at the Doce River Shelf (E01: 11.5 %). The symbiont-bearing species were absent or had low abundance along the transects D and FOZ, except for D03 (18.0 %).

The distribution of epifaunal and infaunal foraminifera species across the study area varied, indicating that epifaunal taxa were more abundant on the Abrolhos Shelf and in some areas of the Paleovalley Shelf, while infaunal taxa were prevalent in the Doce River Shelf. Epifaunal taxa (ranging from 2.9 % to 83.6 %) reached their the highest abundances in samples G01 (83.6 %), F01 (80.3 %), and A01 (72.8 %). Infaunal taxa (ranging from 7.5 % to 93.5 %) achieved the highest values in samples D01 (93.5 %) and FOZ03 (67.9 %).

For a comprehensive summary of the ecological and taxonomic data, see Table 2 and the Supplement (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17313920).

4.3 Benthic foraminiferal assemblages

The dendrogram obtained from Q-mode cluster analysis identified five major groups (M–C, Q–B, H–Q, G–T, and A–P). The groups were analyzed further to determine their characteristics using IndVal analyses, and each group was named based on the abbreviation of its dominant taxa, representing five distinct benthic foraminiferal assemblages distributed along the ESCS (Fig. 4).

Figure 4Distribution map of the five groups in the ESCS (a) based on the groups identified in the dendrogram classification (Q-mode) (b).

The predominant species and main factors in each group, which were used to name the groups, were determined based on the distribution of the main species across the study area and within the groups (Table 3).

Table 3The Indicator Species Analyses (IndVal) based on the dendrogram classification. The indicator factor for each group has a p value of < 0.05. The highest values are highlighted in bold and underlined, and the lowest are in bold and italics.

Group M–C (Miliolinella–Cibicides) includes samples from the southern ESCS and the northern Campos Shelf (Paleovalley Shelf): A01, A02, A03, A04, B01, B02, B03, B04 and C02. The IndVal analysis indicated that Miliolinella subrotunda (8.4 %), Discorbis viladeboeanus (3.5 %), Bolivina striatula (2.3 %), Cibicides spp. (2.1 %), Discorbinella bertheloti (2.0 %), and Cibicides aknerianus (2.0 %) were characteristic taxa of this group. The analysis also showed that the highest averages of the richness (84 taxa per sample), Shannon–Wiener (3.7) and Fisher α (10.4) indexes, and equitability (0.8) were found to have a relevant role in distinguishing this group.

Other aspects that seem to be characteristic of the M–C group were the high density of benthic foraminifera (3755 tests per gram), the high abundance of Cibicides species (9.0 %), and the low abundance of agglutinated taxa (4.3 %). Sediment samples from this group exhibit the highest average content of gravel (8.8 %) and a high content of CaCO3 (62.7 %).

Group Q–B (Quinqueloculina–Bigerina) includes samples C03 and C01, also located on the Paleovalley Shelf. The IndVal analysis indicated that Quinqueloculina cuvieriana (32.1 %), Bigenerina textularioidea (18.1 %), Amphistegina radiata (10.0 %), Eponides cribrorepandus (2.6 %), and Sigmoilopsis schlumbergeri (2.2 %) were the most characteristic taxa of this group. The analysis also showed that the highest average of epifaunal foraminifera (68.5 %) and the highest abundance of agglutinated foraminifera (31 %) were relevant in distinguishing this group.

Other aspects that seem to be characteristic of this group were the lowest average values in terms of the richness (38 taxa per sample), Shannon–Wiener (2.3) and Fisher's α indexes (4.4), and equitability (0.6). Sediment samples from this group exhibit a high average content of gravel (8.5 %) and the highest content of CaCO3 (70.0 %), as well as the lowest content of mud (8.0 %).

Group G–T (Globocassidulina–Trifarina) includes samples FOZ03, FOZ18, D01, D04, F04, and E04, which encompass the Doce River Shelf and the southern portion of the Abrolhos Shelf. The IndVal analysis indicated that Globocassidulina rossensis (19.8 %), Globocassidulina crassa (9.2 %), Trifarina angulosa (6.7 %), Planulina foveolata (3.4 %), Globocassidulina subglobosa (3.2 %), Bolivina lowmani (2.7 %), and Cibicidoides mundulus (2.6 %) were distinguishing taxa of this group. The highest averages of hyaline foraminifera (87 %), benthic foraminifera (83.1 %), infaunal (64 %), planktonic foraminifera (3.0 %), and fragmented planktonic foraminifera (19.2 %) were found to be relevant in distinguishing this group, as was the highest content of mud (42.5 %) and OM (10.7 %).

Another aspect that seems to be characteristic of this group was the lowest abundance of porcelaneous taxa (7.2 %).

Group H–Q (Hanzawaia–Quinqueloculina) includes samples E03, D03, FOZ13, FOZ08, E02, and D02, which also encompass the Doce River Shelf and the southern portion of the Abrolhos Shelf. The IndVal analysis indicated that Hanzawaia boueana (23.4 %), Quinqueloculina spp. (7.7 %), Quinqueloculina lamarckiana (5.4 %), and Elphidium discoidale (3.6 %) were characteristic taxa of this group. The analysis also showed that the highest average of fragmented benthic foraminifera (58.2 %) was relevant in distinguishing this group, along with the highest sand content (91.3 %).

Other aspects that seem to be characteristic of this group were the lowest values in terms of density (798 tests per gram). Sediment samples from this group exhibit the lowest averages of gravel (0.8 %), OM (2.7 %), and CaCO3 (7.2 %).

Group A–P (Articulina–Peneroplis) includes samples G03, G02, F03, F02, G01, F01, and E01, which collectively represent the majority of the Abrolhos Shelf. The IndVal analysis indicated that Articulina sulcata (8.6 %) and Archaias angulatus (3.9 %) were characteristic taxa of this group. The analysis also showed that the highest average in terms of the abundance of porcelaneous (49.5 %) and symbiont-bearing species (15.1 %).

Other aspects that seem to be characteristic of this group were the highest abundance of Peneroplis species (17.8 %), the lowest abundance of infaunal taxa (24 %), and the high abundance of juvenile foraminifera. Sediment samples from this group exhibit a low content of OM (2.4 %).

The ESCS compartments are distinguished by their distinct sediment composition, varied seafloor morphology, sedimentary regimes, and oceanographic characteristics. This section will provide a detailed discussion of the distribution of the defined benthic foraminiferal assemblages within each ESCS compartment previously defined by Bastos et al. (2015) and Vieira et al. (2019).

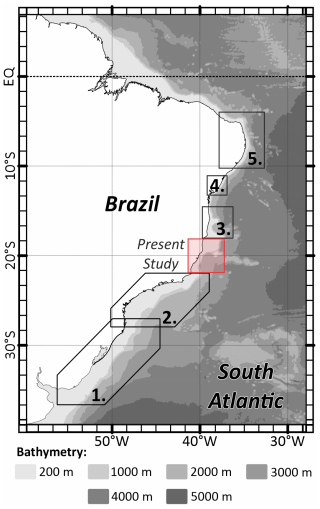

The ESCS's benthic foraminifera fauna include taxa commonly found in the Campos Basin continental shelf right in the south of our present study, as evidenced by the abundance of hyaline genera such as Globocassidulina (Vieira et al., 2015). There are several surveys that relate the benthic foraminiferal assemblages to the continental shelf in the Brazilian margin, but in Fig. 5, we selected some broad latitudinal-study examples in the south of our database, where the sedimentation pattern is much more siliciclastic than carbonate and where there is a constant presence of the hyaline genus of Globocassidulina species, Uvigerina, Bulimina, and Bolivina (and some Brizalina) (Eichler et al., 2012; Burone et al., 2011). There are also some examples in the north of our study area, until the equatorial margin, where the carbonate sedimentation pattern is more frequently marked by the abundance of miliolids and robust and symbiont-bearing foraminifera common to higher-energy and marine-driven environments, such as the genera Quinqueloculina, Amphistegina, and Archaias (Araújo and Machado, 2008; Araújo and Araújo, 2010; Bérgamo et al., 2024).

Figure 5Map showing the distribution of some broad latitudinal studies along the Brazilian Margin. (1) Eichler et al. (2012), (2) Burone et al. (2011), (3) Araújo and Machado (2008), (4) Araújo and Araújo (2010), and (5) Bérgamo et al. (2024).

The following section will discuss the ESCS foraminiferal assemblages with regard to other studies along the Brazilian Margin and all over the world.

5.1 Paleovalley Continental Shelf assemblages: groups M–C and Q–B

The sedimentation regime at the Paleovalley Continental Shelf differs from that of adjacent areas. In this sediment-starved shelf (low terrigenous input), the carbonate sedimentation predominates in the middle and outer shelves. Species from group M–C (Fig. 4, Table 3) inhabit this shelf compartment, dominated by M. subrotunda, Cibicides sp., Bolivina paula, and Discorbis vilardeboanus. This group also presented elevated values of species diversity, indicating a well-established community (Frontalini and Coccioni, 2008). High diversity values are typically indicative of a balanced community of species, greater resilience to natural disturbances, and stable environmental conditions that support a diverse and functionally efficient benthic community (Hill, 1973; Buzas and Hayek, 1998). A sufficient supply of organic matter favors benthic foraminiferal species establishment and diversity (Jorissen et al., 2007; de Almeida et al., 2023).

In the ESCS, the BC incursion on the continental shelf has the potential to promote episodic intrusion of SACW along the Paleovalley Continental Shelf (Palóczy et al., 2016). This intrusion results in the upwellings of this cold and nutrient-rich water mass from the upper slope to the surface waters (Silveira et al., 2020). The nutrient enrichment on the surface waters induces an increase in local primary productivity and, consequently, an increase in the organic matter influx to the seafloor. As a result of this mechanism, the diversity and density of benthic foraminiferal populations might rise in environments characterized by elevated levels of oxygen (Cearreta, 1988; Debenay et al., 2001; Eichler et al., 2012). Eichler et al. (2012), in the south of the Brazil continental margin, related the presence of the SACW to Uvigerina peregrina, a species that was not particularly abundant in the ESCS but is an infauna species like B. paula. In addition, this condition seems to favor M. subrotunda and D. abundances in the ESCS. A similar assemblage was reported by Buosi et al. (2012) in the Mediterranean Sea. These authors found Rosalina vilardeboanus (= Discorbis vilardeboanus) and M. subrotunda in regions with increased organic input. Altenbach et al. (1993) describes how shallow infaunal M. subrotunda exhibits a unique adaptation by constructing dentritic tubes that lift its test several millimeters above the sediment surface, facilitating a temporary epibenthic lifestyle to feed. The high abundance of M. subrotunda in group M–C may highlight its potential role as an indicator of carbonate-rich sediments.

The infaunal species of the genus Bolivina were also found in high abundance on the lower slope of the Espírito Santo Basin (2500–3000 m) by de Almeida et al. (2022). Bolivina species have been demonstrated to serve as indicators of an increase in the availability of more refractory organic matter (Abu-Zied et al., 2008), eventually metabolized by anaerobic bacteria within the sediment (Jorissen and Wittling, 1999).

Species from group Q–B (Fig. 5, Table 3) are distributed near the “Costa das Algas” Environmental Protection Area (CA-EPA) (ICMBio, 2020). The CA-EPA is characterized by a diverse seafloor, featuring a wide variety of marine calcareous and non-calcareous macroalgae, such as rhodoliths (IBAMA, 2006; Holz et al., 2020). This region is characterized by the presence of biolithoclastic and lithoclastic sediments, which collectively create a mosaic of seafloor environments (Gastão et al., 2020; Longo and Amado Filho, 2014).

Group Q–B exhibited the lowest benthic foraminiferal density and diversity indexes and is dominated by Q. cuvieriana and B. textularioidea. The genus Quinqueloculina is widely distributed in marine sediments; however, it is notably more abundant in nearshore and reef or lagoonal environments characterized by phytal substrates. Similar patterns have been reported in reef and lagoonal habitats in Papua New Guinea (Langer and Lipps, 2003) and Bazaruto, East Africa (Langer et al., 2013). On Brazilian continental shelves, the frequency and high abundance of Quinqueloculina species are associated with coastal, high-energy, and warm-water carbonate environments (Araújo and Machado, 2008; Oliveira-Silva et al., 2005; Bérgamo et al., 2024; Eichler et al., 2024).

Disaró (2013) found B. textularioidea associated with sandy sediments, mainly composed of carbonate bioclasts on the outer continental shelf of the Campos Basin. Others studies found B. textularioidea in shallower sediments on the Abrolhos Shelf (Sanches et al., 1995; Araújo and Machado, 2008; Ruschi et al., 2024) and on the upper slope (150 m water depth) of the Potiguar Basin (Santa-Rosa et al., 2021). In this same basin, Disaró et al. (2022) reported B. textularioidea associated with sediments composed of 2 %–11 % of total organic matter (TOC) and >70 % CaCO3. In the ESCS, this species exhibited its highest abundance in bioclastic and coarser sediments, suggesting that B. textularioidea is well-adapted to carbonate environments with moderate to high energy, as reflected in its association with coarse-grained, poorly sorted sediments.

5.2 Doce River and southern Abrolhos Continental Shelf assemblages: groups G–T and H–Q

Groups G–T and H–Q (Fig. 4, Table 3) cover an extensive area of the ESCS, which contains terrigenous deposits in the vicinity of the Doce River mouth (Bastos et al., 2015; Quaresma et al., 2015) and a rhodolith bed on the outer shelf. The species belonging to group G–T inhabit this shelf compartment, distinguished by the high relative abundance of Globocassidulina rossensis.

The dominance of Globocassidulina (e.g., G. rossensis and G. crassa) in group G–T is consistent with its dominance on the upper slope of the Espírito Santo Basin (de Almeida et al., 2022). These authors found a distinct foraminiferal assemblage at 400 m water depth, containing a high abundance of G. rossensis and Trifarina spp. Both species are associated with a substantial flux of metabolizable organic matter, which is in agreement with the observed increased number of infaunal species. These aforementioned findings are in alignment with the results reported by Sousa et al. (2017) from the upper slope of Campos Basin. In the northern Campos Basin, Globocassidulina is associated with outer continental shelf environments, characterized by lower temperatures and high silt content (Vieira et al., 2015). Burone et al. (2011) investigated the southeastern Brazilian margin (from 23 to 28° S), highlighting the occurrence of G. subglobosa in regions influenced by upwelling phenomena, where mesotrophic conditions prevail, which, in group G–T, might be related to an SACW intrusion in the Tubarão Bight region (Palóczy et al., 2016). Such environments generally support a diverse benthic community, which is in contrast to those that are dominated by opportunistic assemblages. In a study of the Pleistocene–Holocene core from the Pelotas Basin, Rodrigues et al. (2018) found a positive correlation between the relative abundance of T. angulosa and TOC content. In the ESCS, T. angulosa is associated with mud sediments containing high OM content.

Group H–Q (Fig. 4, Table 3) is characterized by the high abundance of H. boueana and a notable presence of the porcelaneous foraminifera Quinqueloculina spp. and Peneroplis planatus. This assemblage comprises samples distributed from the Doce River Shelf to the southern portion of the Abrolhos Shelf. This region primarily consists of terrigenous sediments with localized occurrences of biogenic carbonate deposits (Vieira et al., 2019). The occurrence of the symbiont-bearing P. planatus is associated with warm-carbonate waters, such as biofacies reported by Ruschi et al. (2024) at the Abrolhos Depression on the southern Abrolhos Shelf.

Group H–Q appears to represent a transitional assemblage between group G–T, dominated by infaunal species in terrigenous muddy sediments with high OM, and group A–P (Fig. 4a), dominated by epifaunal species in warm-carbonate sandy sediments with low OM. Additionally, the frequency and abundance of Quinqueloculina spp. in group H–Q, along with samples characterized by low mud and OM content, align with one biofacies found by Ruschi et al. (2024), which is dominated by epifaunal species adapted to carbonate-rich and low-OM environments. Group H–Q contains a mixture of infaunal and epifaunal species, similarly to biofacies EH from Ruschi et al. (2024), where Elphidium spp. and H. boueana predominate. The relative abundance of Elphidium and Criboelphidium spp. is higher in group H–Q than in the other groups. This condition might reflect a transitional adaptation. The data presented in our study indicate that group H–Q constitutes a transitional foraminiferal assemblage, representing a transition zone between infaunal-dominated, terrigenous-rich environments (group G–T) and epifaunal-dominated, carbonate-rich environments (group A–P). These findings are indicative that benthic foraminiferal assemblages undergo changes in their composition under different latitudinal environments across the ESCS.

5.3 Abrolhos Continental Shelf assemblage: group A–P

Group A–P is defined by a high abundance and diversity of porcelaneous foraminifera, including symbiont-bearing species (Hallock et al., 2003), such as Peneroplis spp. and Archaias spp. These species are commonly found in warm and carbonate-rich waters. These genera are frequently documented in reef environments of the Brazilian continental shelves (e.g., Sanches et al., 1995; Santa-Rosa et al., 2021; Bérgamo et al., 2024) and worldwide (e.g., Langer and Lipps, 2003; Fajemila et al., 2015; A'ziz et al., 2021).

The carbonate sediments of the Abrolhos Continental Shelf include mud, bioclastic sand, rhodolith beds, and submerged reefs (Bastos et al., 2015; Vieira et al., 2019). The genus Articulina, which was also found in high abundance in group A–P, was identified in the Barrier Reef Tract and Lagoon in British Honduras (Cebulski, 1969). Additionally, agglutinated species such as Textularia agglutinans and Sahulia barkeri have been reported in significant numbers in Safaga Bay, a warm-water carbonate environment in the Red Sea along the Egyptian coast (Haunold, 1999).

The foraminiferal biota identified in this group appears to be largely influenced by two inversely related parameters on the seafloor: sediment grain size and organic matter input. The samples are predominantly sandy and exhibit a lower average content of OM, which may be associated with the presence of mesotrophic to oligotrophic and symbiont-bearing species.

The samples from this group vary from 25 and 50 m and showed a marked abundance of the cosmopolitan species Ammonia spp. (A. parkinsoniana, A. tepida, and juvenile forms), typical of inner and coastal marine environments. Ammonia tepida, a commonly reported species in Brazilian coastal environments (e.g., Debenay et al., 2001; Burone et al., 2007; Teodoro et al., 2009; Díaz et al., 2014), was observed in only three samples: G01, F01 (group A–P), and FOZ03 (group G–T). The FOZ03 sample, the shallowest in the dataset (13 m depth), is located near the Doce River mouth and showed the highest abundance of this species.

-

The benthic foraminiferal assemblages found in this study are closely related to the distinct geomorphology compartments and sedimentary regimes of the ESCS. Each continental shelf compartment (Paleovalley, Abrolhos, and Doce River) supports distinct foraminiferal groups that reflect local sedimentary, geomorphological, and oceanographic conditions.

-

The distribution of benthic foraminiferal assemblages along the ESCS reflects the current environmental mosaic and provides a framework for interpreting past environmental changes.

-

Each assemblage identified in this study (M–C, Q–B, H–Q, G–T, and A–P) can serve as a valuable proxy for reconstructing paleoenvironmental conditions, such as sediment supply, organic matter flux, and oceanographic dynamics.

-

The dominance of carbonate-associated species in the Paleovalley and Abrolhos shelves can be used to identify periods of carbonate sedimentation and reef development in the geological record.

-

The presence of infaunal-dominated assemblages in the Doce River Shelf can indicate periods of increased terrigenous input and organic matter deposition.

-

The transitional nature of group H–Q can help identify shifts between siliciclastic and carbonate-dominated environments, providing insights into past changes in sediment sources and oceanographic conditions.

The data discussed in this paper are available in the Supplement (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17313920, Rodrigues, 2025).

All of the figured specimens have been placed in plummer slides, reposited in the Laboratory of Marine Geosciences (LaboGeo) collection at the Department of Oceanography and Ecology at the Universidade Federal do Espirito Santo (Brazil).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-44-633-2025-supplement.

ARR, FKA, and RMM conceived the study. ARR, FKA, and PPR performed the morphological identifications and the statistical analyses. PPR made the SEM images. CFG, VSQ, and KAJ organized the abiotic parameters. ARR, FKA, VSQ, PPR, CFG, RRM, KAJ, and ACB wrote the paper. ARR, FKA, VSQ, and KAJ created the figures.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Advances and challenges in modern and benthic foraminifera research: a special issue dedicated to Professor John Murray”. It is not associated with a conference.

This study was funded by PETROBRAS. We acknowledge the Espírito Santo Basin Assessment Project (AMBES, CENPES/PETROBRAS S.A.) for collecting the sediment samples. The BPA/CENPES/PETROBRAS laboratory is acknowledged for the help with the sample preparation. We thank Luis P. Maia (UFC) and Fabian Sá (UFES) for providing the sedimentological data. The LUCCAR/UFES (MCT/FINEP/CT-INFRA-PROINFRA 01/2006) laboratory is acknowledged for providing the SEM images. We also thank Mariana Coelho Rodrigues for helping in the foraminiferal analysis. We thank the LaboGeo members for sharing their knowledge about the study area, and we are especially grateful to Fernanda V. Vieira for her help in drafting the study area map. We are grateful to the editor, Andrew Gooday, and to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism and valuable comments, which lead to substantial improvement of the paper, and to Francesca Sangiorgi for her help in improving the final version. This article is a contribution to a Journal of Micropalaeontology special issue dedicated to John W. Murray, whose books, articles, and presence have influenced and supported researchers worldwide throughout his productive lifetime and will continue to do so for many future generations. Thanks are given for the TMS funding dedicated to this special issue.

This research has been supported by the Petrobras (grant no. PETROBRAS S.A.).

This paper was edited by Francesca Sangiorgi and Andy Gooday and reviewed by Luisa Bergamin and two anonymous referees.

Abu-Zied, R. H., Rohling, E. J., Jorissen, C. F., Casford, J. S. L., and Cooke, S.: Benthic foraminiferal response to changes in bottom-water oxygenation and organic carbon flux in the eastern Mediterranean during LGM to Recent times, Mar. Micropaleontol., 67, 46–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2007.08.006, 2008.

Aguiar, V. M. C., Bastos, A. C., Quaresma, V. S., D'Azeredo Orlando, M. T., Vedoato, F., Cavichini, A. S., and Baptista Neto, J. A.: Trace metals distribution along sediment profiles from the Doce River Continental Shelf (DRCS) 3 years after the biggest environmental disaster in Brazil, the collapse of the Fundão Dam, Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci., 63, 103001, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2023.103001, 2023.

Altenbach, A. V., Heeger, T., Linke, P., Spindler, M., and Thies, A.: Miliolinella subrotunda (Montagu), a miliolid foraminifer building large detritic tubes for a temporary epibenthic lifestyle, Mar. Micropaleontol., 20, 293–301, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(93)90038-Y, 1993.

Araújo, T. M. F. and Araújo, H. A. B.: Assembleias de foraminíferos dos sedimentos superficiais da plataforma continental e talude superior do norte da Bahia, Rev. Geol., 23, 115–134, 2010.

Araújo, T. M. F. and Machado, A. J.: Análise sedimentar e micropaleontológica (foraminíferos) de seções quaternárias do talude continental superior do norte da Bahia, Brasil, Pesqui. Geociênc., 35, 97–113, https://doi.org/10.22456/1807-9806.17941, 2008.

Arruda, W. Z., Campos, E. J. D., Zharkov, V., Soutelino, R. G., and Silveira, I. C. A.: Events of equatorward translation of the Vitoria eddy, Cont. Shelf Res., 70, 61–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2013.05.004, 2013.

A'ziz, A. N. A., Minhat, F. I., Pan, H.-J., Shaari, H., Saelan, W. N. W., Azmi, N., Manaf, O. A. R. A., and Ismail, M. N.: Reef foraminifera as bioindicators of coral reef health in southern South China Sea, Sci. Rep., 11, 8890, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88404-3, 2021.

Barbosa, C. F., Silva, D. F. N., Bellot, A. C. F., Hallock, P., Araujo, S. L., Arantes, R. C. M., and Seoane, J. C. S.: An integrated approach to environmental health assessment of a coral reef ecosystem based upon foraminifera, J. Foraminifer. Res., 55, 60–77, https://doi.org/10.61551/gsjfr.55.1.60, 2025.

Bastos, A. C., Quaresma, V. S., Marangoni, M. B., D'Agostini, D. P., Bourguignon, S. N., Cetto, P. H., Silva, A. E., Amado Filho, G. A., Moura, R. L., and Collins, M.: Shelf morphology as an indicator of sedimentary regimes: a synthesis from a mixed siliciclastic-carbonate shelf on the eastern Brazilian margin, J. S. Am. Earth Sci., 63, 125–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2015.07.003, 2015.

Bérgamo, D. B., Lacerda, J. N. L., Araripe, R. V. C., Ferreira Júnior, A. V., and Oliveira, D. H.: Benthic foraminifera as depth estimators in the tropical carbonate shelf of northeastern Brazil, Cont. Shelf Res., 276, 105246, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2024.105246, 2024.

Bernardino, A. F., Berenguer, V., and Ribeiro-Ferreira, V. P.: Bathymetric and regional changes in benthic macrofaunal assemblages on the deep Eastern Brazilian margin, SW Atlantic, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 111, 110–120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2016.02.016, 2016.

Boersma, A.: Handbook of common Tertiary Uvigerina, Microclimates Press, Stony Point, New York, 207 pp., 1984.

Bolli, H. M., Beckman, J. P., and Saunders, J. B.: Benthic foraminiferal biostratigraphy of the South Caribbean Region, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511564406, 1994.

Boltovskoy, E., Giussani, G., Watanabe, S., and Wright, R.: Atlas of Benthic Shelf Foraminifera of the Southwest Atlantic, Dr. W. Junk B. V. Publishers, Oxford, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-9188-0, 1980.

Bourguignon, S. N., Bastos, A. C., Quaresma, V. S., Vieira, F. V., Pinheiro, H., Amado-Filho, G. M., de Moura, R. L., and Teixeira, J. B.: Seabed morphology and sedimentary regimes defining fishing grounds along the eastern Brazilian shelf, Geosciences, 8, 91, https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8030091, 2018.

Buosi, C., Armynot du Châtelet, E., and Cherchi, A.: Benthic foraminiferal assemblages in the current-dominated strait of Bonifacio (Mediterranean Sea), J. Foraminifer. Res., 42, 39–55, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.42.1.39, 2012.

Burone, L., Valente, P., Pires-Vanin, A. M. S., de Mello e Sousa, S. H., Mahiques, M. M., and Braga, E.: Benthic foraminiferal variability on a monthly scale in a subtropical bay moderately affected by urban sewage, Sci. Mar., 71, 775–792, https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.2007.71n4775, 2007.

Burone, L. B., Sousa, S. H. M., Mahiques, M. M., Valente, P., Ciotti, A., and Yamashita, C.: Benthic foraminiferal distribution on the southeastern Brazilian shelf and upper slope, Mar. Biol., 158, 159–179, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-010-1549-7, 2011.

Buzas, M. A. and Hayek, L.-A. C.: SHE analysis for biofacies identification, J. Foraminifer. Res., 28, 233–239, 1998.

Castelo, W. F. L., Martins, M. V. A., Martínez-Colón, M., da Silva, L. C., Menezes, C., Oliveira, T., Sousa, S. H. M., Aguilera, O., Laut, L., Laut, V., Duleba, W., Frontalini, F., Bouchet, V. M. P., Armynot du Châtelet, E., Francescangeli, F., Geraldes, M. C., Reis, A. T., and Bergamashi, S.: Bioaccumulation of potentially toxic elements in Ammonia tepida (foraminifera) from a polluted coastal area, J. S. Am. Earth Sci., 115, 103741, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103741, 2022.

Castro, B. and Miranda, L. B.: Physical oceanography of the western Atlantic continental shelf between 4° N and 34° S, in: The Sea – The Global Coastal Ocean, Vol. 10, edited by: Brink, K. and Robinson, A., Wiley, New York, 209–251, 1998.

Cearreta, A.: Distribution and ecology of benthic foraminifera in the Santoña estuary, Spain, Rev. Esp. Paleontol., 3, 23–38, https://doi.org/10.7203/sjp.25140, 1988.

Cearreta, A., Irabien, M. J., Leorri, E., Yusta, I., Quintanilla, A., and Zabaleta, A.: Environmental transformation of the Bilbao estuary, N. Spain: microfaunal and geochemical proxies in the recent sedimentary record, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 44, 487–503, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00261-2, 2002.

Cebulski, D. E.: Foraminiferal population and faunas in barrier-reef tract and lagoon, British Honduras, Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Mem., 11, 311–328, 1969.

Clarke, K. R. and Warwick, R. M.: Similarity-based testing for community pattern: the 2-way layout with no replication, Mar. Biol., 118, 167–176, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00699231, 1994.

Corliss, B. H.: Microhabitats of benthic foraminifera within deep-sea sediments, Nature, 314, 435–438, https://doi.org/10.1038/314435a0, 1985.

Corliss, B. H. and Chen, C.: Morphotype patterns of Norwegian deep-sea benthic foraminifera and ecological implications, Geology, 16, 716–719, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1988)016<0716:MPONSD>2.3.CO;2, 1988.

Costa Júnior, A. A., Quaresma, V. S., Turbay, C. V. G., Oliveira, N., Leite, M. D. A., Vieira, F. V., and Bastos, A. C.: Sedimentary patterns and spatial distributions of heavy minerals along the continental shelf in the Espírito Santo State, Brazil, Rev. Bras. Geociênc., 45, 431–436, https://doi.org/10.11137/1982-3908_2022_45_43136, 2022.

Culver, S. J. and Buzas, M. A.: The effects of anthropogenic habitat disturbance, habitat destruction, and global warming on shallow marine benthic foraminifera, J. Foraminifer. Res., 25, 204–211, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.25.3.204, 1995.

D'Agostini, D. P., Bastos, A. C., Amado-Filho, G. M., Vilela, C. G., Thaís, C. S., Oliveira, T. C. S., Webster, J. M., and Moura, R. L.: Morphology and sedimentology of the shelf-upper slope transition in the Abrolhos continental shelf (East Brazilian Margin), Geo-Mar. Lett., 39, 117–134, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00367-019-00562-6, 2019.

de Almeida, F. K., de Mello, R. M., Rodrigues, A. R., and Bastos, A. C.: Bathymetric and regional benthic foraminiferal distribution on the Espírito Santo Basin slope, Brazil (SW Atlantic), Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 181, 103688, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2022.103688, 2022.

de Almeida, F. K., Mello, R. M., and Bastos, A. C.: The influence of submarine canyons-related processes on recent benthic foraminiferal distribution, Espírito Santo Basin, Southeastern Brazil, Mar. Micropaleontol., 179, 102212, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2023.102212, 2023.

Debenay, J.-P., Tsakiridis, E., Soulard, R., and Grossel, H.: Factors determining the distribution of foraminiferal assemblages in Port Joinville Harbor (Ile d'Yeu, France): the influence of pollution, Mar. Micropaleontol., 43, 75–118, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-8398(01)00023-8, 2001.

Dias, J. A.: A análise sedimentar e o conhecimento dos sistemas marinhos: Uma Introdução à Oceanografia Geológica II – Análise Textural, Universidade do Algarve, 91 pp., 2004.

Díaz, T. L., Rodrigues, A. R., and Eichler, B. B.: Distribution of foraminifera in a subtropical Brazilian estuarine system, J. Foraminifer. Res., 44, 90–108, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.44.2.90, 2014.

Disaró, S. T.: Caracterização da plataforma continental da Bacia de Campos (Brasil, SE) fundamentada em foraminíferos bentônicos recentes, PhD thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 163 pp., https://lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/172465 (last access: 20 April 2025), 2013.

Disaró, S. T., Totah, V. I., Watanabe, S., Ribas, E. R., and Pupo, D. V.: Biodiversidade Marinha da Bacia Potiguar – Foraminifera, in: 1st Edn., Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, ISBN 978-65-5729-015-6, 2022.

Donnici, S., Serandrei-Barbero, R., Bonardi, M., and Sperle, M.: Benthic foraminifera as proxies of pollution: The case of Guanabara Bay (Brazil), Mar. Pollut. Bull., 64, 2015–2028, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.06.024, 2012.

Dufrene, M. and Legendre, P.: Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach, Ecol. Monogr., 67, 345–366, https://doi.org/10.2307/2963459, 1997.

Eichler, P. P. B., Eichler, B. B., Miranda, L. B., Pereira, E. R. M., Kfouri, P. B. P., Pimenta, F. M., Bérgamo, A. L., and Vilela, C. G.: Benthic foraminiferal response to variations in temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen and organic carbon, in the Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Anu. Inst. Geociênc., 26, 36–51, https://doi.org/10.11137/2003_0_36-51, 2003.

Eichler, P. P. B., Rodrigues, A. R., Eichler, B. B., Braga, E. S., and Campos, E. J. D.: Tracing latitudinal gradient, river discharge and water masses along the subtropical South American coast using benthic Foraminifera assemblages, Braz. J. Biol., 72, 95–102, https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842012000400010, 2012.

Eichler, P. P. B., Eichler, B. B., Pimenta, F. M., Pereira, E. R. M., and Vital, H.: Evaluation of environmental and ecological effects due to the accident in an oil pipe from Petrobras in Guanabara Bay, RJ, Brazil, Open J. Mar. Sci., 4, 298–315, https://doi.org/10.4236/ojms.2014.44027, 2014.

Eichler, P. P. B., Vital, H., and Gomes, M. P.: Marine sediments from mesophotic reefs as indicators of offshore vortex in the Açu reef (Northeast, Brazil), J. Aquac. Mar. Biol., 13, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.15406/jamb.2024.13.00389, 2024.

Fajemila, O. T., Langer, M. R., and Lipps, J. H.: Spatial patterns in the distribution, diversity and abundance of benthic foraminifera around Moorea (Society Archipelago, French Polynesia), PLoS ONE, 10, e0145752, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145752, 2015.

Fouet, M. P. A., Schweizer, M., Singer, D., Richirt, J., Quinchard, S., and Jorissen, F. J.: Unravelling the distribution of three Ammonia species (Foraminifera, Rhizaria) in French Atlantic Coast estuaries using morphological and metabarcoding approaches, Mar. Micropaleontol., 188, 102353, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2024.102353, 2024.

Frontalini, F. and Coccioni, R.: Benthic foraminifera for heavy metal pollution monitoring: a case study from the central Adriatic Sea coast of Italy, Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 76, 404–417, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2007.07.024, 2008.

Gastão, F. G. C., Silva, L. T., Lima Junior, S. B., Fernandes, L. F. L., Leal, C. A., Gobira, A. B., and Maia, L. P.: Marine habitats in conservation units on the southeast coast of Brazil, Braz. J. Dev., 6, 22145–22180, https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv6n4-399, 2020.

Geslin, E., Debenay, J.-P., Duleba, W., and Bonetti, C.: Morphological abnormalities of foraminiferal tests in Brazilian environments: comparison between polluted and non-polluted areas, Mar. Micropaleontol., 45, 151–168, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-8398(01)00042-1, 2002.

Gooday, A. J.: Deep-sea benthic foraminiferal species which exploit phytodetritus: characteristic features and controls on distribution, Mar. Micropaleontol., 22, 197–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(93)90043-W, 1993.

Hallock, P., Lidz, B. H., Cockey-Burkhard, E. M., and Donnelly, K. B.: Foraminifera as Bioindicators in Coral Reef Assessment and Monitoring: The FORAM Index, Environ. Monit. Assess., 81, 221–238, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021337310386, 2003.

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T., and Ryan, P. D.: PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis, Palaeontol. Electron., 9 pp., http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm (last access: 2 August 2025), 2001.

Haunold, T. G.: Ecologically controlled distribution of recent Textulariid foraminifera in subtropical, carbonate-rich Safaga Bay (Red Sea, Egypt), Beitr. Paläontol., 24, 69–85, 1999.

Hayward, B. W., Sabaa, A., and Grenfell, H. R.: Benthic foraminifera and the late Quaternary (last 150 ka) paleoceanographic and sedimentary history of the Bounty Trough, east of New Zealand, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol., 211, 59–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.04.007, 2004.

Hill, M. O.: Diversity and evenness: A unifying notation and its consequences, Ecology, 54, 427–432, https://doi.org/10.2307/1934352, 1973.

Holbourn, A., Henderson, A. S., and MacLeod, N.: Atlas of benthic foraminifera, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118452493, 2013.

Holz, V. L., Bahia, R. G., Karez, C. S., Vieira, F. V., Moraes, F. C., Vale, N. F., Sudatti, D. B., Salgado, L. T., Moura, R. L., Amado-Filho, G. M., and Bastos, A. C.: Structure of Rhodolith Beds and Surrounding Habitats at the Doce River Shelf (Brazil), Diversity, 12, 75, https://doi.org/10.3390/d12020075, 2020.

Hyams-Kaphzan, O., Almogi-Labin, A., Sivan, D., and Benjamini, C.: Benthic foraminifera assemblage change along the southeastern Mediterranean inner shelf due to fall-off of Nile-derived siliciclastics, Neues Jahrb. Geol. Paläontol. Abh., 248, 315–344, https://doi.org/10.1127/0077-7749/2008/0248-0315, 2008.

IBAMA – Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis: Relatório final da proposta de criação das unidades de conservação “Área de Proteção Ambiental Costa das Algas” e “Refúgio de Vida Silvestre de Santa Cruz” na faixa costeira dos municípios da Serra, Fundão e Aracruz e região marinha confrontante, Estado do Espírito Santo, MMA/Gerência Executiva do IBAMA no Estado do Espírito Santo, Vitória-ES, https://www.gov.br/icmbio/pt-br/assuntos/biodiversidade/unidade-de-conservacao/unidades-de-biomas/marinho/lista-de-ucs/revis-de-santa-cruz/arquivos/plano_de_manejo___versao___livro_digital_compactado.pdf (last access: 2 August 2025), 2006.

ICMBio – Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade: Marine Environmental Protection Area Costa das Algas (MPA-CA), https://www.icmbio.gov.br/apacostadasalgas/ (last access: 6 June 2025), 2020.

ICMBio – Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade: Área de Proteção Ambiental Costa das Algas e Refúgio de Vida Silvestre de Santa Cruz, https://www.icmbio.gov.br/apacostadasalgas (last access: 6 June 2025), 2023.

Jones, R. W.: The Challenger foraminifera, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 160 pp., ISBN 978-0198540960, 1994.

Jorissen, F. J. and Wittling, I.: Ecological evidence from live-dead comparisons of benthic foraminiferal faunas off Cape Blanc (Northwest Africa), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol., 149, 151–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00198-9, 1999.

Jorissen, F. J., Fontanier, C., and Thomas, E.: Paleoceanographical proxies based on deep-sea benthic foraminiferal assemblage characteristics, in: Developments in Marine Geology, Vol. 1, edited by: Hillaire-Marcel, C. and De Vernal, A., Elsevier, 263–325, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-5480(07)01012-3, 2007.

Jorissen, F. J., Fouet, M. P. A., Singer, D., and Howa, H.: The Marine Influence Index (MII): A tool to assess estuarine intertidal mudflat environments for the purpose of foraminiferal biomonitoring, Water, 14, 676, https://doi.org/10.3390/w14040676, 2022.

Kaminski, M. A. and Gradstein, F. M.: Atlas of Paleogene cosmopolitan deep-water agglutinated foraminifera, Grzybowski Found. Spec. Publ. 10, Grzybowski Foundation, 547 pp., ISBN 9788391238585, 2005.

Kaminski, M. A., Boersma, A., Tyszka, J., and Holbourn, A. E. L.: Response of deep-water agglutinated foraminifera to dysoxic conditions in the California Borderland basins, in: Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Agglutinated Foraminifera, Grzybowski Foundation Special Publication 3, Grzybowski Foundation, 131–140, ISBN-13 978-8-390-11642-6, 1995.

Langer, M. R. and Lipps, J. H.: Foraminiferal distribution and diversity, Madang Reef and Lagoon, Papua New Guinea, Coral Reefs, 22, 143–154, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-003-0298-1, 2003.

Langer, M. R., Thissen, J. M., Makled, W. A., and Weinmann, A. E.: The foraminifera from the Bazaruto Archipelago (Mozambique), N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh., 267, 155–170, https://doi.org/10.1127/0077-7749/2013/0302, 2013.

Larsonneur, C.: La cartographie des depots meubles sur le plateau continental français: méthode mise au point et utilisée en manche, J. Rech. Océanogr., 2, 33–39, 1977.

Leite, Y. L. R., Costa, L. P., Loss, A. C., Rocha, R. G., Batalha-Filho, H., Bastos, A. C., Quaresma, V. S., Fagundes, V., Paresque, R., Passamani, M., and Pardini, R.: Neotropical forest expansion during the last glacial period challenges refuge hypothesis, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 1008–1013, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1513062113, 2016.

Loeblich, A. J. R. and Tappan, H.: Foraminiferal genera and their classification, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-5760-3, 1988.

Loeblich, A. R. and Tappan, H.: Foraminifera of the Sahul Shelf and Timor Sea, Cushman Found. Foraminifer. Res. Spec. Publ. 31, Cushman Found., 1–661, ISBN 9781970168204, 1994.

Longo, L. L. and Amado Filho, G. M.: O conhecimento da fauna marinha bentônica brasileira através dos tempos, Hist. Ciênc. Saúde-Manguinhos, 21, 995–1010, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702014000300011, 2014.

Magurran, A. E.: Measuring Biological Diversity, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 256 pp., ISBN-13 978-0-632-05633-0, 2004.

Maia, L. P., Castelo-Branco, M. P. N., Soares, R. S., Catunda B. N., Bastos, A. C., Leal, C. A., and Marcon, E. H.: Sedimentologia da Margem Continental da Bacia do Espírito Santo e Norte da Bacia de Campos, in: Relatório Final do Projeto de Caracterização Ambiental Regional da Bacia do Espírito Santo e parte norte da Bacia de Campos (PCR-ES), Anexo II, Petrobras, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015.

Majewski, W., Szczuciński, W., and Gooday, A. J.: Unique benthic foraminiferal communities (stained) in diverse environments of sub-Antarctic fjords, South Georgia, Biogeosciences, 20, 523–544, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-523-2023, 2023.

Mazzini, P. L. F. and Barth, J. A.: A comparison of mechanisms generating vertical transport in the Brazilian coastal upwelling regions, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 118, 5977–5993, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JC008924, 2013.

McGann, M., Holzmann, M., Bouchet, V. M. P., Disaró, S. T., Eichler, P. P. B., Haig, D. W., Himson, S. J., Kitazato, H., Pavard, J.-C., Asteman, I. P., Rodrigues, A. R., Tremblin, C. M., Tsuchiya, M., Williams, M., O'Brien, P., Asplund, J., Axelsson, M., and Lorenson, T. D.: Analysis of a human-mediated microbioinvasion: the global spread of the benthic foraminifer Trochammina hadai Uchio, 1962, J. Micropalaeontol., 44, 275–317, https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-44-275-2025, 2025.

Mello, R., Leckie, R. M., Fraass, A. J., and Thomas, E.: Upper Maastrichtian-Eocene benthic foraminiferal biofacies of the Brazilian margin, western South Atlantic, in: Proceedings of the Ninth International Workshop on Agglutinated Foraminifera, Grzybowski Foundation Special Publication 22, Grzybowski Foundation, 119–161, ISBN 978-83-941956-1-8, 2017.

Murray, J. W.: Ecology and applications of benthic foraminifera, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 0 521 82839 2, 2006.

Oliveira, N., Bastos, A. C., Quaresma, V. S., and Vieira, F. V.: The use of Benthic Terrain Modeler (BTM) in the characterization of continental shelf habitats, Geo-Mar. Lett., 40, 1087–1097, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00367-020-00642-y, 2020.

Oliveira-Silva, P., Barbosa, C. F., and Soares-Gomes, A.: Distribution of macrobenthic foraminifera on the Brazilian continental margin between 18° S–23° S, Braz. J. Geol., 35, 209–216, https://doi.org/10.25249/0375-7536.2005352209216, 2005.

Palóczy, A., Brink, K. H., Silveira, I. C. A., Arruda, W. Z., and Martins, R. P.: Pathways and mechanisms of offshore water intrusions on the Espírito Santo Basin shelf (18° S–22° S, Brazil), J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 121, 5134–5163, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JC011468, 2016.

Patterson, R. T. and Richardson, R. H.: A taxonomic revision of the Unilocular foraminifera, J. Foraminifer. Res., 17, 212–226, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.17.3.212, 1987.

Pawlowski, J., Holzmann, M., and Tyszka, J.: New supraordinal classification of Foraminifera: Molecules meet morphology, Mar. Micropaleontol., 100, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2013.04.002, 2013.

Peeters, F., Ivanova, E., Conan, S., Brummer, G.-J., Ganssen, G., Troelstra, S., and van Hinte, J.: A size analysis of planktic foraminifera from the Arabian Sea, Mar. Micropaleontol., 36, 31–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-8398(98)00026-7, 1999.

Pereira, A. F., Belem, A. L., Castro, B. M., and Geremias, R.: Tide-topography interaction along the Eastern Brazilian Shelf, Cont. Shelf Res., 25, 1521–1539, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2005.04.008, 2005.

Quaresma, V. S., Catabriga, G., Bourguignon, S. N., and Godinho, E., Bastos, A. C.: Modern sedimentary processes along the Doce river adjacent continental shelf, Braz. J. Geol., 45, 635–644, https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-488920150030274, 2015.

Queiroz, H. M., Ferreira, A. D., Ruiz, F., Bovi, R. C., Deng, Y., de Souza Júnior, V. S., Otero, X. L., Bernardino, A. F., Cooper, M., and Ferreira, T. O.: Early pedogenesis of anthropogenic soils produced by the world's largest mining disaster, the “Fundão” dam collapse, in southeast Brazil, Catena, 219, 106625, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106625, 2022.

Rodrigues, A.: Supplementary material (JM-2025-19) – From a river mouth to reef: Benthic foraminifera assemblages reveal ecological dynamics in a mixed carbonate–siliciclastic Brazilian continental shelf, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17313920, 2025.

Rodrigues, A. R., Pível, M. A. G., Schmitt, P., de Almeida, F. K., and Bonetti, C.: Infaunal and epifaunal benthic foraminifera species as proxies of organic matter paleofluxes in the Pelotas Basin, south-western Atlantic Ocean, Mar. Micropaleontol., 144, 38–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2018.05.007, 2018.

Rodrigues, R. R. and Lorenzzetti, J. A.: A numerical study of the effects of bottom topography and coastline geometry on the South-East Brazilian coastal upwelling, Cont. Shelf Res., 21, 371–394, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4343(00)00094-7, 2001.

Ruschi, A. G., Rodrigues, A. R., Cetto, P. H., and Bastos, A. B.: Pleistocene to early Holocene paleoenvironmental evolution of the Abrolhos depression (Brazil) based on benthic foraminifera, Sci. Rep., 14, 24443, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75223-5, 2024.

Sanches, T. M., Kikuchi, R. K. P., and Eichler, B. B.: Ocorrência de foraminíferos recentes em Abrolhos, Bahia, Spec. Publ. Inst. Oceanogr. São Paulo, 11, 37–47, 1995.

Santa-Rosa, L. C. C., Disaró, S. T., Totah, V., Watanabe, S., and Guimarães, A. T. B.: Living Benthic Foraminifera from the Surface and Subsurface Sediment Layers Applied to the Environmental Characterization of the Brazilian Continental Slope (SW Atlantic), Water, 13, 1863, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13131863, 2021.

Sen Gupta, B. K.: Modern Foraminifera, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 371 pp., ISBN 1-4020-0598-9, 1999.

Silveira, I. C. A., Napolitano, D. C., and Farias, I. U.: Water Masses and Oceanic Circulation of the Brazilian Continental Margin and Adjacent Abyssal Plain, in: Brazilian Deep-Sea Biodiversity, edited by: Sumida, P. Y. G., Bernardino, A. F., and De Léo, F. C., Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 7–36, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53222-2_2, 2020.

Soares, R. S.: Novas Proposições Metodológicas Para o Calcímetro de Bernard e Caracterização dos Sedimentos Marinhos do Espírito Santo, MS thesis, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil, 90 pp., http://repositorio.ufc.br/handle/riufc/25568 (last access: 2 August 2025), 2017.

Sousa, S. H. M., Yamashita, C., Nagai, R. H., Martins, M. V. A., Ito, C., Vicente, T., Taniguchi, N., Burone, L., Fukumoto, M., Aluizio, R., and Koutsoukos, E. A. M.: Foraminíferos bentônicos no talude continental, platô de São Paulo e cânions da Bacia de Campos, in: Ambiente Bentônico: caracterização ambiental regional da Bacia de Campos, Atlântico Sudoeste, V. 3, edited by: Falcão, A. P. C. and Lavrado, H. P., Elsevier, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 111–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-85-352-7263-5.50005-9, 2017.

Soutelino, R. G., Silveira, I. C. A., Gangopadhyay, A., and Miranda, J. A.: Is the Brazil Current eddy-dominated to the north of 20° S?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L03607, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL046276, 2011.

Souza, W. L. and Knoppers, B. A.: Fluxos de água e sedimentos a costa leste do Brasil: relações entre a tipologia e as pressões antrópicas, Geochim. Bras., 17, 57–74, 2003.

StatSoft: STATISTICA data analysis software system, StatSoft Inc., http://www.statsoft.com (last access: 2 August 2025), 2001.

Suguio, K.: Introdução à Sedimentologia, Edgard Blücher Ltda, São Paulo, Brazil, 317 pp., 1973.

Tapia, R., Le, S. L. H., Bassetti, M.-A., Lin, I.-T., Lin, H.-L., Chang, Y.-P., Jiann, K.-T., Wang, P.-L., Lin, J.-K., Babonneau, N., Ratzov, G., Hsu, S.-K., and Su, C.-C.: Planktic-benthic foraminifera ratio (%P) as a tool for the reconstruction of paleobathymetry and geohazard: A case study from Taiwan, Mar. Geol., 453, 106922, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2022.106922, 2022.

Teodoro, A. C., Duleba, W., and Lamparelli, C.: Associações de foraminíferos e composição textural da região próxima ao emissário submarino de esgotos domésticos de Cigarras, Canal de São Sebastião, SP, Brasil, Pesqui. Geociênc., 36, 79–94, https://doi.org/10.22456/1807-9806.17876, 2009.

van Morkhoven, F. P. C. M., Berggren, W. A., and Edwards, A. S.: Cenozoic cosmopolitan deep-water benthic foraminifera, Bull. Cent. Rech. Explor.-Prod. Elf-Aquitaine Mém. 11, Bull. Cent. Rech. Explor.-Prod. Elf-Aquitaine, 421 pp., ISBN 2901026206, 1986.

Vieira, F. S., Koutsoukos, E. A. M., Machado, A. J., and Dantas, M. A. T.: Biofaciological zonation of benthic foraminifera of the continental shelf of Campos Basin, SE Brazil, Quatern. Int., 377, 18–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2014.12.020, 2015.

Vieira, F. V., Bastos, A. C., Quaresma, V. S., Leite, M. L., Costa Jr., A., Oliveira, K. S. S., Dalvi, C. F., Bahia, R. G., Holz, V. L., Moura, R. L., and Amado-Filho, G. M.: Along-shelf changes in mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sedimentation patterns, Cont. Shelf Res., 187, 103964, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2019.103964, 2019.

Vilela, C. G.: Taphonomy of benthic foraminiferal tests of the Amazon shelf, J. Foraminifer. Res., 33, 132–143, https://doi.org/10.2113/0330132, 2003.

WoRMS Editorial Board: Foraminifera, World Register of Marine Species, https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1410 (last access: 10 August 2025), 2022.

Ximenes Neto, A. R., Quaresma, V. S., Menandro, P. S., Cetto, P. H., and Bastos, A. C.: Drowned barriers and valleys: A morphological archive of base level changes in the western South Atlantic, Mar. Geol., 477, 107404, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2024.107404, 2024.