the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Lower Jurassic calcareous nannofossil taxonomy revisited according to the Neuquén Basin (Argentina) record

Micaela Chaumeil Rodríguez

Emanuela Mattioli

Juan Pablo Pérez Panera

Standard Early Jurassic biostratigraphic studies were performed in the boreal and Tethys realms (western Europe and northern Africa), and biozonations from these areas are the most accurate of the world. Comparatively, investigations in the Pacific realm are scarce, and, in Argentina, they are limited to contributions based on oil-industry subsurface and outcrop reports for the Los Molles Formation. A focused systematic analysis was not previously addressed in the area. The Neuquén Basin in west–central Argentina offers a unique opportunity to study the Early Jurassic calcareous nannofossil history in the south-eastern Pacific Ocean. Calcareous nannofossil assemblages from El Matuasto I section (Los Molles Formation) represent one of the earliest records for the Early Jurassic in the Neuquén Basin and one of the few for the eastern Pacific realm. A detailed systematic analysis allowed the recognition of major bioevents and a comparison with worldwide associations and biostratigraphic schemes. A thorough taxonomic discussion of the Early Jurassic nannofossil species of the Neuquén Basin is presented for the first time. Herein, the taxonomic features of coccoliths recorded in the Neuquén Basin are settled. The age of the calcareous nannofossil assemblages recorded in El Matuasto I is early–late Pliensbachian, covering the NJT4a to NJT4c subzones. Similarities between the Neuquén Basin and localities from the proto-Atlantic region suggest an effective connection between the Pacific and Tethyan basins during the Pliensbachian.

- Article

(6703 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Calcareous nannofossils are remarkable components of Mesozoic marine successions, although their documented distribution may show geographical and temporal biases depending on the discontinuities of the sedimentary record. Classic Lower Jurassic biostratigraphic studies have been primarily built upon locations in the boreal and Tethys realms, namely western Europe and North Africa (e.g. Stradner, 1963; Prins, 1969; Barnard and Hay, 1974; Perch-Nielsen, 1985a; Bown, 1987b; Bown et al., 1988; de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993; de Kaenel et al., 1996; Bown and Cooper, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999; Fraguas et al., 2007, 2015, 2018; Mattioli et al., 2013; Peti et al., 2017; Ferreira et al., 2019). Biozonations from these areas are the most accurate and complete compared to any other part of the world. Several works have been undertaken in Tethyan localities like northern and central Italy (Cobianchi, 1990, 1992; Reale et al., 1992; Baldanza and Mattioli, 1992; Lozar, 1995; Nini et al., 1995; Stoico and Baldanza, 1995; Mattioli, 1996; Picotti and Cobianchi, 1996; Bucefalo Palliani and Mattioli, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999; Cobianchi and Picotti, 2001; Mattioli and Pittet, 2004; Chiari et al., 2007; Bottini et al., 2016), Spain (Perilli, 2000; Tremolada et al., 2005; Fraguas et al., 2007, 2015, 2018; Fraguas and Erba, 2010; Perilli et al., 2010; Sandoval et al., 2012; Menini et al., 2019), Germany (Prins, 1969; Grün et al., 1974; Crux, 1984; Bown, 1987a; Dockerill, 1987; Prins and Driel, 1987; Fraguas et al., 2013), Portugal (Hamilton, 1977, 1979; Baldanza and Mattioli, 1992; de Kaenel and Bergen, 1996; de Kaenel et al., 1996; Veiga de Oliveira et al., 2007a, b; Suchéras-Marx et al., 2010; Reggiani et al., 2010; López-Otálvaro et al., 2012; Mattioli et al., 2013; Plancq et al., 2016; Ferreira et al., 2019), northern France (Peti et al., 2017), North Africa (de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993; Bodin et al., 2010, 2016; Mercuzot et al., 2019; Baghli et al., 2022), and the United Kingdom (Prins, 1969; Noël, 1972; Rood and Barnard, 1972; Rood et al., 1973; Barnard and Hay, 1974; Moshkovitz, 1979; Hamilton, 1982; Bown, 1987a; Crux, 1987b; Dockerill, 1987; Prins and Driel, 1987; Menini et al., 2021). Taxonomic revisions were also performed, but since Bown (1987b) none of them have dealt with muroliths except Fraguas and Erba (2010).

Comparatively, investigations in the Pacific realm are scarce (Bown, 1987b; Fantasia et al., 2018) and in Argentina are restricted to Los Molles Formation, represented by few general studies (Bown, 1987b, 1992; Ballent et al., 2000, 2011; Angelozzi et al., 2010; Al-Suwaidi et al., 2010, 2016) or contributions based on oil-industry subsurface and outcrop reports (Angelozzi, 1988; Bown and Ellison, 1995; Angelozzi and Ronchi, 2002; Vergani et al., 2003; Angelozzi and Pérez Panera, 2013, 2016; Pérez Panera and Angelozzi, 2015; Gutiérrez Pleimling et al., 2021). However, a focused systematic analysis was not previously addressed in the area.

In this context, the Neuquén Basin, located in west–central Argentina, offers a unique opportunity to study the Early Jurassic calcareous nannofossil history in the south-eastern Pacific Ocean. The basin yields a Lower Jurassic marine transgression from the palaeo-Pacific and records an extensive sedimentary succession (Arregui et al., 2011).

Calcareous nannofossil assemblages from Los Molles Formation represent the earliest record for the Early Jurassic in the Neuquén Basin and one of the few for the eastern Pacific realm (Bown, 1992; Fantasia et al., 2018). This contribution aims at characterizing the Pliensbachian calcareous nannofossil assemblages of the south-eastern Palaeo-Pacific region through a detailed study of El Matuasto I section (Neuquén Basin, Argentina). A detailed systematic analysis allowed recognition of major events and a comparison with worldwide associations and biostratigraphic schemes.

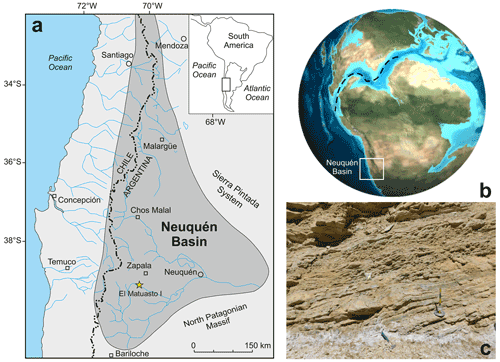

The Neuquén Basin is located in west–central Argentina, constituting a series of marine and continental sub-basins that have developed behind the Pacific margin of the South American Plate (Fig. 1a) (Legarreta and Uliana, 1999). Since the beginning of the sedimentary filling in the Late Triassic–Early Jurassic, it has accumulated more than 7000 m of Mesozoic deposits (Arregui et al., 2011). During the Pliensbachian–Aalenian interval and in the Tithonian, marine sedimentation was widespread in the Neuquén Basin, while it was restricted to a few areas in other time intervals. Until the Early Cretaceous, this basin was part of the south-eastern Pacific Ocean and had a unique record of marine micro- and macrofossils in the world. The detailed stratigraphic characterizations made on well-exposed outcrops resulted in a thorough understanding of the basin evolution (Groeber, 1918; Weaver, 1931; Stipanicic, 1969; Riccardi, 1983; Gulisano et al., 1984; Legarreta and Gulisano, 1989; Riccardi and Gulisano, 1990; Legarreta and Uliana, 1996, 1999; Lanés, 2005; Leanza, 2009; Arregui et al., 2011; Legarreta and Villar, 2012).

Figure 1(a) Geographical setting of the Neuquén Basin and the El Matuasto I section (Argentina) (adapted after Howell et al., 2005). (b) Palaeogeographic reconstruction for the Early Jurassic showing the possible connection between the Pacific and Tethys oceans during the Pliensbachian (adapted after Global Paleogeography, http://plate-tectonic.narod.ru/globalpaleogeophotoalbum.html, last access: 12 March 2022). (c) View of the El Matuasto I section, Los Molles Formation.

The Los Molles Formation (Weaver, 1931) is mainly composed of grey and dark grey mudstones, with fine to medium sandstones interbedded and variable organic content. Sedimentation corresponds to a marine environment with restricted conditions (Arregui et al., 2011) and represents the earliest Pacific marine transgression in the basin (Legarreta and Uliana, 1996; Legarreta and Villar, 2012). The age of the formation covers the Hettangian to Callovian, considering its total extension in the different areas of the basin (Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleimling, 1995; Vergani et al., 1995; Legarreta and Uliana, 1996; Cruz et al., 1999; Veiga et al., 2009; Riccardi, 2008a; Arregui et al., 2011; Legarreta and Villar, 2012; Spalletti et al., 2012; Sales et al., 2014; Casadío and Montagna, 2015).

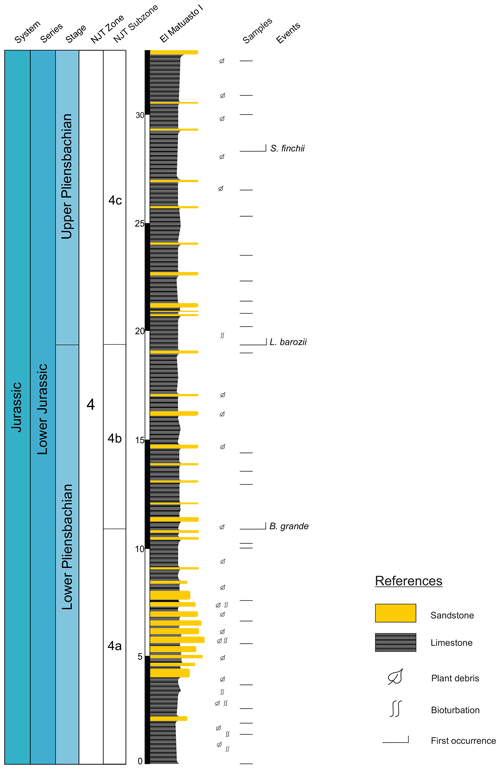

The El Matuasto I section is located approximately 45 km south of the city of Zapala (Neuquén Province) and 1 km from the Picún Leufú River bridge along the Ruta Nacional 40 (Fig. 1b–c). It is represented by a 33 m thick succession of mudstones with thin fine–medium sandstone intercalations. Sand beds are interpreted as turbidites, where the basin experienced episodes of continental sediment input. Bioturbation and plant debris are common throughout the sequence.

A set of 26 samples from the El Matuasto I section (Los Molles Formation) was analysed for calcareous nannofossils. The preparation method consists of a slight modification of the technique described by Beaufort et al. (2014). A small amount of powdered rock was diluted with 30 mL of water. The suspension was poured on a coverslip in a Petri dish. The cover slide was weighed before applying the suspension with the study material. Once the sediment was settled (after 4 h), the water was carefully removed to avoid turbulence. The coverslip was then dried to remove the remaining water, weighed again, and then mounted on a microscope slide using Norland 61 optical glue. This method enables us to calculate the absolute abundance (nannofossil per gram of sediment) using the formula described by Menini et al. (2019).

Identification and counting of calcareous nannofossils were performed using a Leica DMP 750 petrographic microscope at 1000× magnification under crossed polars. Photographs were taken with a Leica MC 170 HD camera. For each sample 300 specimens were counted, thus ensuring that the probability of not recovering a rare species is below 5 % (Fatela and Taborda, 2002). In the slides for which a low nannofossil abundance made it difficult to count 300 specimens, the counting stopped at 450 fields of view (FOV; the area of one FOV is 0.0069 mm2).

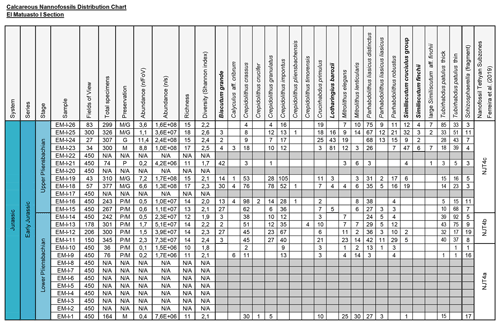

All nannofossil data were integrated in a distribution chart (Fig. 2). The absolute abundance (as nannofossils per gram of sediment) and preservation index are also indicated. Preservation is a discrete scale based on the general aspect of the specimens (Roth, 1984). G: good – most specimens exhibit little or no secondary alterations and delicate structures such as spines are preserved in most cases. M: moderate – specimens exhibit some degree of overgrowth and/or dissolution (identification of species not compromised). P: poor – the effects of overgrowth and/or dissolution are very intense (identification of species is impaired but possible in some cases).

Figure 2Distribution chart of calcareous nannofossils from El Matuasto I, Los Molles Formation. Preservation index: P (poor), M (moderate), G (good), N/A (not applicable); grey cell (barren). Abundance (n/FoV): nannofossils per field of view. Abundance (n/s): nannofossils per gram of sediment. Biozones consigned after Ferreira et al. (2019). Marker species in bold.

The systematic palaeontology follows the criteria by de Vargas et al. (2007) for subclass level and up and Young and Bown (1997) and Bown and Young (1997) for levels below subclass.

For biostratigraphic analysis, the following nannofossil events are used after Gradstein et al. (2012): FO (first occurrence), LO (last occurrence), LCO (last common occurrence). They are correlated with the biozones of Bown et al. (1988), Bown and Cooper (1998), de Kaenel and Bergen (1993), Mattioli and Erba (1999), and Ferreira et al. (2019); they appear in the text as NJ (Nannofossil Jurassic) and NJT (Nannofossil Jurassic Tethyan) zones. Standard and Neuquén Basin Ammonite Zonations (SAZ and NAZ, respectively) (Riccardi, 2008b) are correlated with these nannofossil biozones.

A total of 16 samples of the El Matuasto I section yielded calcareous nannofossils, while 10 were barren. The general preservation of the assemblage is moderate to good, with overall better preservation towards the upper part of the section. Sample richness varies between a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 18 species per sample. Stratigraphic distribution of nannofossils and other features are given in Fig. 2.

For all the recovered species, the entire synonymies provided in the literature, the original papers describing the holotype, and the available literature illustrating a given species were carefully checked. The systematic palaeontology below is thus based upon a careful revisitation of previous literature and presents a synonymy list as complete as possible. For each species, remarks are provided with respect to the original diagnosis, which also make reference to descriptions provided in the literature.

As far as the coccolith morphology is concerned, we refer to Young (1992) for the murolith and placolith description and to Bown (1987b) for the protolith and loxolith structure. The protolith rim structure of muroliths comprises a dominant distal shield and a proximal shield, both showing a vertical (distal) extension (see Bown, 1987b, text-fig. 6B). The distal shield is composed of elements joined along sutures which are perpendicular to the coccolith base without imbrication. The protolith rim structure is possessed by the genera Crucirhabdus, Mitrolithus, and Parhabdolithus. The loxolith rim structure of muroliths comprises a dominant distal shield and a proximal shield with a vertical (distal) extension (see Bown, 1987b, text-fig. 6A). The distal shield is composed of tall, narrow, steeply inclined and imbricating laths. The loxolith rim is possessed by the genera Crepidolithus and Tubirhabdus. The placolith rim structure possesses elements forming a slightly concave–convex shield developing in the horizontal plane parallel to the cell surface as opposed to the murolith tall upright rims, which were vertically orientated. The radiating placolith rim structure comprises a proximal and distal shield, both unicyclic (Bown, 1987b, text-fig. 7A). The distal shield is composed of blade-like laths lying side by side, with the suture lines between each element orientated radially to the central area of the coccolith. The genera which display this structure include Biscutum, Similiscutum, and Calyculus. The imbricating placolith rim structure consists of a bicyclic distal shield, a unicyclic proximal shield, and a connecting inner wall (Bown, 1987b, text-fig. 7B). The distal shield outer cycle is composed of blade-like laths which are imbricating and joined along sutures with anti-clockwise inclination. The only genus considered here which displays this structure is Lotharingius.

4.1 Systematic palaeontology

-

Division HAPTOPHYTA Hibberd ex Edvardsen and Eikrem in Edvardsen et al., 2000

-

Class PRYMNESIOPHYCEAE Hibberd, 1976; emend. Cavalier-Smith in Cavalier-Smith et al., 1996

-

Subclass CALCIHAPTOPHYCIDAE de Vargas et al., 2007

-

Grade “HETEROCOCCOLITHS” Braarud et al., 1955a, b

-

Order EIFFELLITHALES Rood et al., 1971

-

Family CHIASTOZYGACEAE Rood et al., 1973 emend. Varol and Girgis, 1994

-

Genus Crepidolithus Noël, 1965b

-

Type species. Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b

-

Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b

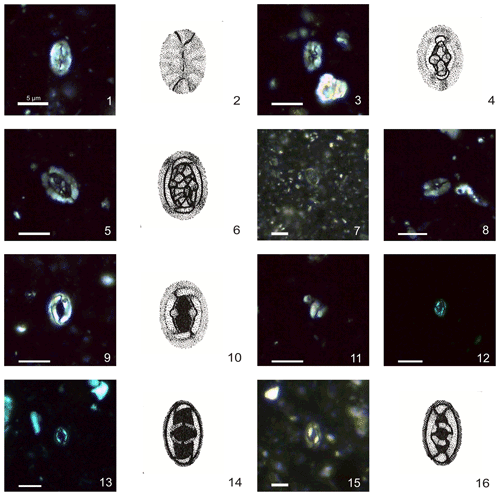

(Plate 1, figs. 1–2)

-

1954 Discolithus crassus Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, p. 144, pl. 15, figs. 12–13, text-fig. 49.

-

1965a Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954); Noël, p. 5, text-figs. 17–21.

-

1965b Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954); Noël, pl. 2, figs. 3–7; pl. 3, fig. 1–5; text-figs. 17–21.

-

non 1969 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Prins, pl. 1, fig. 5C.

-

1973 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins, 1969; Rood et al., pl. 2, fig. 4.

-

1979 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Goy in Goy et al., 1979, pl. 2, fig. 1.

-

non 1979 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Medd, p. 54, pl. 1, figs. 7–8.

-

1981 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Goy, pl. 5, figs. 8, 10–11 (non fig. 9); pl. 6, fig. 1.

-

1982 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Hamilton in Lord, pl. 3.1, fig. 4 (non fig. 3).

-

non 1986 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Young et al., pl., fig. M.

-

1987a Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Bown, pl. 1, figs. 1–2.

-

1987b Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Bown, pp. 16–17, pl. 1, figs. 6–11; pl. 12, figs. 5–6.

-

1988 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Angelozzi, p. 142, pl. 2, figs. 4–5.

-

1992 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1985) Bown, 1987b. Cobianchi, fig. 22i–l.

-

1994 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Goy et al., pl. 7, figs. 3–4.

-

1998 Crepidolithus timorensis (Kristan-Tollmann, 1988a) Bown in Bown and Cooper, pl. 4.9, figs. 13–14 (= small C. crassus).

-

1998 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.1, fig. 1; pl. 4.9, figs. 1–2.

-

1998 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Parisi et al., pl. 4, fig. 2.

-

1999 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Mattioli and Erba, p. 364–365, pl. 1, fig. 8, tex–fig. 8.

-

2000 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Walsworth-Bell, p. 51, fig. 4.7; p. 90, fig. 6.3.

-

2007 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Fraguas et al., p. 232–233, pl. 1, fig. 1.

-

2008 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Aguado et al., fig. 5.11–12.

-

2008 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Fraguas et al., pl. 1, fig. 1.

-

2010 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Reggiani et al., pp. 2–3, pl. 1, figs. 3–6.

-

2010 “small crassus” Suchéras-Marx et al., fig. 7.

-

2013 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Mattioli et al., pl. 1, fig. 14.

-

2014 Crepidolithus cantabriensis. Fraguas, fig. 3f (non figs. 3a–e).

-

2015 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Casellato and Erba, pl. 1.18–19, and “small” C. crassus pl. 1.20.

-

2017 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Peti et al., fig. 5I; figs. S.2 34–35 (appendix F).

-

2019 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Menini et al., p. 16, pl. 1., figs. 4–5.

-

2019 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Ferreira et al., p. 8, pl. 1, fig. 21.

-

2021 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Fraguas et al., fig. 9, CM.249.

Plate 1Calcareous nannofossils from El Matuasto I, Los Molles Formation, Neuquén Basin. All pictures from LM under crossed nicols and distal view unless specified. Scale bar: 5 µm. All illustrations adapted after Prins (1969). (1, 2) Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b, EM-I-18 (YT.RMP_N.000012.10). (3, 4) Crepidolithus crucifer Prins ex Rood et al., 1973 emend. Fraguas and Erba, 2010, EM-I-16 (YT.RMP_N.000012.9). (5, 6) Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b, thick morphotype, EM-I-12 (YT.RMP_N.000012.5). (7) Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b, thin morphotype, EM-I-11 (YT.RMP_N.000012.4). (8) Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1985) emend. Bown, 1987b, EM-I-16 (YT.RMP_N.000012.9). (9) Crepidolithus impontus Grün, Prins and Zweili, 1974, EM-I-10 (YT.RMP_N.000012.3). (10) Crepidolithus impontus Grün, Prins and Zweili, 1974, slightly tilted, EM-I-19 (YT.RMP_N.000012.11). (11) Crepidolithus timorensis (Kristan-Tollmann, 1988a) Bown in Bown and Cooper, 1998, EM-I-13 (YT.RMP_N.000012.6). (12) Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973, tiny morphotype, EM-I-1 (YT.RMP_N.000012.1). (13, 14) Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973, thin morphotype, EM-I-11 (YT.RMP_N.000012.4). (15, 16) Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973, thick morphotype, EM-I-10 (YT.RMP_N.000012.3).

Range. Sinemurian–Tithonian (Bown and Cooper, 1998).

Occurrence. Given the wide range of C. crassus, this species has been recorded in the entire studied interval. The FO of this species is used by some authors to mark the NJ2–NJ3 zone boundary (Barnard and Hay, 1974; Bown and Cooper, 1998; Fraguas et al., 2015).

Remarks. The original diagnosis of Discolithus crassus describes an “elliptical slightly elongated, thick coccolith without an elevated rim, exhibiting an undulated longitudinal median line, interrupted in its centre by divergent lateral lines and few punctuations (? perforations)” (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954, pp. 115–176). Noël (1965b, p. 88) emended this diagnosis, stating that it is “a typical Crepidolithus”. The punctuation reported by Deflandre and Fert (1954) might be the result of poor preservation of the specimen that they illustrate under light microscope (LM). The later description by Bown (1987b; p. 16) reports a “broad, high, elliptical rim with a vacant central area often reduced to a lenticular slit… The broader the wall the narrower the central area”. Actually, scanning electron microscope (SEM) pictures (Bown, 1987b, pl. 1, figs. 6–9, p. 15) show a variable-sized, vacant central area. In fact, Noël (1965b) and Bown (1987b) observed a certain variability in the central area of C. crassus, which can be slightly open. Suchéras-Marx et al. (2010) reported two different-sized coccolith morphotypes, named “small crassus” with a mean size of 6.5 µm and “large crassus” with a mean size of 8.5 µm. Fraguas and Erba (2010) performed biometric analysis on C. crassus and C. crucifer, and they differentiated the two species on the basis of biometry, concluding that C. crassus has a smaller size (mean size 6.91 µm) than C. crucifer (mean size 8.96 µm) (see Fig. 3). Despite the small average size of C. crassus reported by Fraguas and Erba (2010), the measured specimens virtually integrate both the small crassus and large crassus of Suchéras-Marx et al. (2010). In fact, the differences between C. crassus and C. crucifer also concern the central-area structures.

-

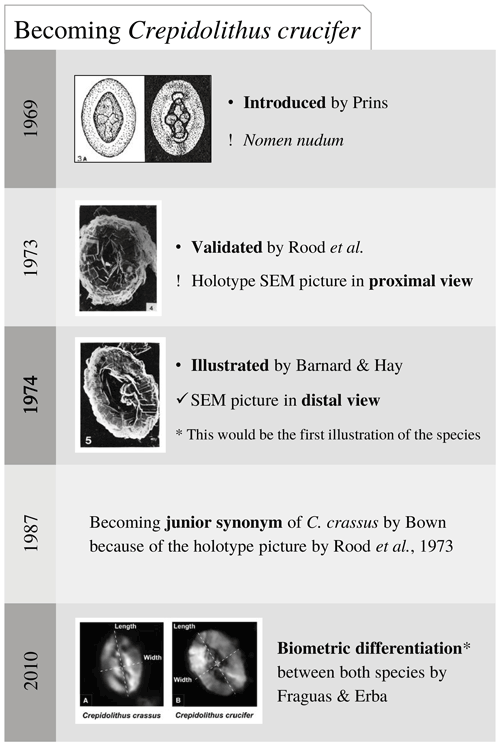

Crepidolithus crucifer Prins ex Rood et al., 1973 emend. Fraguas and Erba, 2010

(Plate 1, figs. 3–4)

-

1969 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins, p. 551, pl. 1, fig. 3a (non fig. b) (nomen nudum).

-

non 1973 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins, 1969. Rood et al., p. 374, pl. 2, fig. 4.

-

1974 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Barnard and Hay, pl. 1, fig. 5; pl. 4, fig. 5.

-

1977 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Hamilton, pp. 586, pl. 3, fig. 10.

-

1978 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Hamilton, pp. 183–184, pl. 7, fig. 2.

-

1979 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Medd, p. 54, pl. 1, fig. 8 (non fig. 7).

-

1981 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b; Goy, pl. 5, fig. 9 (non figs. 8, 10–11).

-

1982 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Hamilton in Lord, pl. 3.1, fig. 1.

-

?1986 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Young et al., pl., fig. M.

-

1992 Crepidolithus cavus Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Cobianchi, fig. 22h.

-

1994 Crepidolithus sp. Noël, 1973. Gardin and Manivit, p. 230–231, pl. 1, figs. 13–14.

-

2003 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Asgar-Deen et al., pp. 58–59, fig. 11, text-fig. 11.

-

2010 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins ex Rood et al., 1973 emend. Fraguas and Erba, p. 134, fig. 3b.

-

2015 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Casellato and Erba, pl. 1.22.

-

2019 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins, 1969. Menini et al., p. 16, pl. 1, fig. 12.

-

2019 Crepidolithus crucifer Prins, 1969. Ferreira et al., p. 8, pl. 1, fig. 22.

Range. Pliensbachian (Fraguas and Erba, 2010).

Occurrence. This species has been recorded in the entire studied interval.

Remarks. This species was introduced by Prins (1969) as nomen nudum. Prins (1969) showed a drawing in which a thick cross spanned a narrow central area, and the cross is composed of granular calcite crystals. Rood et al. (1973) provided a SEM picture showing a Crepidolithus in proximal view with a very reduced central area without visible structure, as well as a description stating, “a species of Crepidolithus with a cruciform structure in the central area” (p. 374). According to the latter, Bown (1987b) put C. crucifer in synonymy with C. crassus. However, C. crassus possesses a vacant central area. Thus, the presence of a cruciform structure in the central area of C. crucifer represents a valuable morphological difference between the two species. Moreover, Fraguas and Erba (2010) nicely illustrated by means of SEM and biometry that C. crassus and C. crucifer can be clearly differentiated. They provided an emended diagnosis: “A robust, thick and elliptical species of Crepidolithus with a relatively narrow and large central area filled by a structure consisting of a cross aligned along the major and minor axes of the ellipse that sometimes appears weakly developed” (p. 134). Although they include the presence of a cross aligned to the major and minor axes of the ellipse, in their picture (fig. 3b) the cross is not visible but a coarse granulation. In their description they stated that the central-area structure often appears as irregular grains. This peculiar morphology is also visible in the SEM picture of C. crucifer showed by Barnard and Hay (1974) (although broken) and in the Medd (1979) C. crassus (see Fig. 3). Other characteristics allowing a differentiation of C. crucifer from C. crassus are a bigger size for C. crucifer (Fraguas and Erba, 2010) and the fact that the elements of the distal shield appear quite large, providing an irregular outline under LM.

-

Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b

Range. Pliensbachian–Toarcian, Early Jurassic (Bown and Cooper, 1998).

Occurrence. Both morphotypes of this species have been recorded in the entire studied interval.

Remarks. This elliptical coccolith has a low distal rim and a large, wide central area filled with small, granular calcite crystals. Bown (1987b) explains that this species shows variable thickness of the distal shield, and, as a consequence, the central-area opening can be more or less developed. This difference is figured in many previous publications (Mattioli et al., 2013; Peti et al., 2017). Crepidolithus granulatus is herein presented as two morphotypes described separately below. The rim thickness variation reflects likely a palaeoenvironmental or palaeogeographical control, but further biometric study is necessary to better constrain the differences between the two morphotypes.

-

Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b (thick morphotype)

(Plate 1, figs. 5–6)

-

1977 Ethmorhabdus aff. E. gallicus Noël, 1965b. Hamilton, pl. 1, fig. 6.

-

1981 Crepidolithus impontus Goy, pl. 6, figs. 7–8.

-

1984 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Crux, fig. 11.1.

-

1987b Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, p. 17, pl. 1, figs. 14–15; pl. 12, figs. 1, 5.

-

1998 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.1, figs. 2–3; pl. 4.9, fig. 3.

-

2007a Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 5.P.

-

2007b Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 1.

-

2013 large Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Mattioli et al., pl. 1.15.

-

non 2013 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Rai and Jain, pl. 2, figs. 2a–c; pl. 3, figs. 3a–c.

-

2014 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Reolid et al., fig. 6 (thick).

-

non 2015. Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Casellato and Erba, pl. 1.22.

-

non 2016. Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Rai et al., fig. 2.19a–b.

-

2019 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Menini et al., pl. 1.

-

2019 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Ferreira et al., pl. 1 (Peniche74).

Remarks. Coccoliths displaying a thick distal shield and a wide central area filled with slightly disorganized bulky calcite crystals. Usually, the central boss is not recognizable.

-

Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b (thin morphotype)

(Plate 1, fig. 7)

-

1969 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Prins, pl. 1, fig. 5C.

-

1977 Ethmorhabdus aff. E. gallicus Noël, 1965b. Hamilton, pl. 1, figs. 4–5.

-

1984 Crepidolithus crassus (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954) Noël, 1965b. Crux, fig. 11.2.

-

1987b Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, p. 17, pl. 1, figs. 12–13.

-

1998 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.9, figs. 4–5.

-

2006 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 1, fig. 15.

-

2010 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Reggiani et al., pl. 1, figs. 7–8.

-

2014 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Reolid et al., fig. 6 (thin).

-

2015 Crepidolithus cavus Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Casellato and Erba, pl. 1.21.

-

2017 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Peti et al., fig. 5K; fig. S.2 22 (appendix F).

-

2019 Crepidolithus granulatus Bown, 1987b. Ferreira et al., pl. 1 (Peniche97).

Remarks. Specimens with a thin distal rim and a wide central area filled with small calcite crystals where a small boss is distinguishable.

-

Crepidolithus impontus Grün, Prins and Zweili, 1974

(Plate 1, figs. 9–10)

-

non 1969 Crepidolithus cavus Prins, pl. 1, fig. 4C (nomen nudum).

-

1974 Crepidolithus cavus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Barnard and Hay, pl. 1, fig. 2.

-

1974 Crepidolithus impontus Grün, Prins and Zweili, pp. 310–311, pl. 2, figs. 1–3.

-

1978 Crepidolithus cavus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Hamilton, pl. 7, fig. 3.

-

1979 Crepidolithus impontus Grün, Prins and Zweili, 1974 emend. Goy in Goy et al., p. 39, pl. 2, fig. 2.

-

1981 Crepidolithus impontus Grün, Prins and Zweili, 1974; Goy, pp. 28–29, pl. 6, figs. 2–6 (non figs. 7–8); pl. 7, fig. 1. text-fig. 5.

-

1982 Crepidolithus cavus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Hamilton in Lord, pl. 3.1, fig. 2.

-

1987b Crepidolithus cavus Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Bown, pp. 13–16, pl. 1, figs. 4–5; pl. 12, figs. 3–4.

-

1998 Crepidolithus impontus (Grün et al., 1974) Goy, 1979. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.1, figs. 4–5; pl. 4.9, figs. 6–7.

-

2006 Crepidolithus cavus Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 2, fig. 16.

-

2007 Crepidolithus cavus Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Fraguas et al., pp. 233–236, pl. 1, fig. 2.

-

2014 Crepidolithus cantabriensis Fraguas, pp. 33–36, figs. 3a–e (non fig. f).

-

2019 Crepidolithus cavus/impontus Prins ex Rood et al., 1973. Menini et al., p. 16, pl. 1, fig. 11.

Range. Pliensbachian–Bajocian (Bown and Cooper, 1998).

Occurrence. This species has been recorded in the entire studied interval.

Remarks. Crepidolithus impontus was first introduced by Grün et al. (1974, p. 310), who describe “a large coccolith whose central area is spanned in the proximal side by a bridge made up of two rows of elements parallel to the short axis of the ellipse. A central process is absent”. Goy (in Goy et al., 1979, p. 39) emended this diagnosis and proposed “A species of the genus Crepidolithus with a wall composed of calcite laths very inclined and overlapping. The central area is spanned by a bridge parallel to minor axis of the ellipse having in its centre a very small spine”. Grün et al. (1974) stated in their remarks that C. impontus resembles to C. cavus sensu Prins, 1969 (nomen nudum). The diagnosis by Goy (in Goy et al., 1979) closely resembles that of C. cavus, which is a species of Crepidolithus with a bridge along the minor axis of the elliptical central area (Rood et al., 1973, p. 375). Accordingly, Bown (1987b) considers C. impontus to be a junior synonym of C. cavus. Eventually, Bown and Cooper (1998) use C. cavus for early Pliensbachian forms with a prominent spine (which according to the description might rather be considered P. liasicus) without figuring it and C. impontus to refer to late Pliensbachian specimens with a wide central area spanned by a delicate bridge and no spine. The specimen of C. cavus drawn by Prins (1969, nomen nudum) figures a murolith with a relatively reduced central area and two prominent insertions of a central structure. The overall features of this specimen may look like a Parhabdolithus liasicus. Thus, C. cavus informally introduced by Prins (1969) was validated by Rood et al. (1973), who show for the holotype an SEM image having a relatively narrow central area and a prominent spine. Also, because the SEM image is very poor, sutural lines of the distal shield are not visible and this specimen resembles a Parhabdolithus. Grün et al. (1974) came to a similar conclusion, stating that the specimen figured by Rood et al. (1973) looks like a distal view of Parhabdolithus marthae. Accordingly, de Kaenel et al. (1996) proposed the new combination Parhabdolithus cavus (Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973). Thereby, C. cavus in Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al. (1973) should be considered either P. cavus or a junior synonym of P. liasicus Deflandre, 1952.

The confusion between C. cavus (or P. liasicus) and C. impontus is partly due to the loss of the bridge of C. impontus that can be broken in poorly preserved material, making the central area empty; however, the insertions of the bridge are still visible in the wide central area. Also, a certain variability can be observed in the wideness of the central area. Crepidolithus cantabriensis introduced by Fraguas (2014) is pro parte considered to be a C. impontus here. In the LM images shown by Fraguas (2014, figs. 3a–e) it is difficult to see the insertions of the bridge because the pictures were not taken at 45∘. In her original diagnosis, Fraguas describes C. cantabriensis as “A medium-sized, normal to narrowly elliptical species of Crepidolithus with an open central area. Its thick proximal shield extends distally to form a collar which appears to be a distal inner cycle. Its bicyclic rim extinction pattern results in a sigmoidal interference figure” (p. 35). However, this diagnosis is invalid because the sigmoidal extinction pattern is the result of the optical discontinuity existing between the proximal and distal shield at 45∘, which is also a typical feature of C. impontus.

-

Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1985) emend. Bown, 1987b

(Plate 1, fig. 8)

-

1984 Crepidolithus ocellatus Crux, p. 168, figs. 11.3, 5–6, 14.6–7.

-

1985 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis Crux, p. 31 (nomen nudum).

-

1987b Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1985) emend. Bown, pp. 17–18, pl. 1, figs. 16–18; pl. 2, figs. 1–3; pp. 74–75, pl. 12, figs. 9–10.

-

1992 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1985) Bown, 1987b. Baldanza and Mattioli, pl. 1, fig. 3.

-

non 1992. Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1985) Bown, 1987b. Cobianchi, p. 104, figs. 22i–l.

-

1994 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987b. Goy et al., pl. 7, figs. 1–2.

-

1998 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis Crux, 1985. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.1, figs. 9–10; pl. 4.9, figs. 11–12.

-

1999 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987b. Mattioli and Erba, pp. 364–365, pl. 1, fig. 7.

-

2000 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987b. Walsworth-Bell, p. 51, fig. 4.7; p. 90, fig. 6.3.

-

2008 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis (Crux, 1985) Bown, 1987b. Fraguas et al., pl. 1, fig. 2.

-

2017 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis Crux, 1985. Peti et al., p. 11, fig. 5J.

-

2019 Crepidolithus pliensbachensis Crux, 1985. Ferreira et al., p. 8, pl. 1, fig. 26.

Range. Hettangian–Pliensbachian (Bown and Cooper, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999).

Occurrence. The presence of this species in the El Matuasto I is very rare and only recorded within the NJT4c subzone (spanning Davoei and the very base of the Margaritatus SAZ in Ferreira et al., 2019), where its LO happens. The LO reported by Bown and Cooper (1998) and Mattioli and Erba (1999) within the ibex zone probably corresponds to the LCO registered by Ferreira et al. (2019) in the same ammonite zone of Portugal. Crepidolithus pliensbachensis is considered a good marker species in the boreal and Tethys realms for the Early Jurassic (Bown et al., 1988; Bown and Cooper, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999). According to Angelozzi and Pérez Panera (2016), the LO of this species is a useful event in the Neuquén Basin, and it occurs within the Fanninoceras fannini NAZ, which is considered the time equivalent of the upper part of the Davoei and Margaritatus SAZs (Riccardi, 2008b). In this study, its presence is scarce but continuous, and hence we consider C. pliensbachensis to be an important element to make correlations with other regions.

Remarks. A typical Crepidolithus with a thick distal rim-wall and a reduced, lenticular central area spanned by a small spine, typically bow-tie-shaped, which is very diagnostic in LM.

-

Crepidolithus timorensis (Kristan-Tollmann, 1988a) Bown in Bown and Cooper, 1998

(Plate 1, fig. 11)

-

1988a Timorhabdus timorensis Kristan–Tollmann, pp. 74–75, pl. 1, fig. 6.; pl. 2, figs. 1–6.

-

1995 “small” Crepidolithus. Lozar, p. 110, pl. 1, fig. 3–4.

-

1998 Crepidolithus timorensis (Kristan-Tollmann, 1988a) Bown in Bown and Cooper, pl. 4.1, figs. 11–12; non pl. 4.9, figs. 13–15.

Range. Sinemurian–Pliensbachian (Bown and Cooper, 1998; this study).

Occurrence. Crepidolithus timorensis is assigned to the Sinemurian of Timor (Bown, 1992; Bown and Cooper, 1998). Here we found it in the early Pliensbachian within the NJT4b subzone, probably corresponding to the LO of this species, as previously reported by Lozar (1995, northern Italy and southern France), Mattioli et al. (2013, Portugal), Peti et al. (2017, northern France), and Ferreira et al. (2019, Portugal). This represents the first record of the species in the Neuquén Basin. Reworking is not considered due to the absence of older marine sediments in the area, even though they are present in the north of the basin (Riccardi et al., 1988, 1991; Legarreta and Uliana, 1996; Riccardi, 2008a; Arregui et al., 2011; Legarreta and Villar, 2012).

Remarks. Kristan-Tollmann (1988a, p. XVIV/86) provided the diagnosis of this species: “…broadly elliptical coccolith with high and blocky distal shield. The elements forming the distal shield are elongated and enlarged at their extremity. The central-area size is therefore reduced. The spine is short, ending at or just above the rim. The proximal shield is flat and composed of small elements. In the centre is a weakly developed rhombic structure, made evident by few loose elements (see holotype figs. 3, 5, pl. 2). The elements of the proximal shield are arranged to form two perpendicular furrows, aligned with the major and minor axes of the ellipse. In the case of poorly preserved coccoliths or etched specimens, only the central hole and the cross–shaped furrow can be seen proximally (see plate 2, fig. 1,2,6)”. Crepidolithus timorensis is observed in this study as a small coccolith (less than 4.5 µm) with an irregular outline due to the large size of the elements forming the distal shield. The small spine often appears as a small cluster of irregular calcite crystals. Lozar (1995; p. 110) identified a “small” Crepidolithus described as an “elliptical coccolith very similar to C. crassus with a comparable blocky structure, but smaller in size; the elongated central area is closed by a wavy suture”. Despite the fact that this description does not match the original diagnosis of Crepidolithus timorensis, the pictures provided correspond to the species because the irregular spine can be seen in one of them. The “small” Crepidolithus mentioned in Cobianchi (1992, p. 104) or C. timorensis pictured by Bown and Cooper (1998) in pl. 4.1, figs. 11–12 should not be confused with the C. crassus “small morphotype” introduced by Suchéras-Marx et al. (2010). Conversely, the pictures shown by Bown and Cooper (1998) pl. 4.9, figs. 13–14 as C. timorensis are C. crassus small morphotypes. In fact, C. timorensis differs from the C. crassus small morphotype due to its smaller size (4.5 µm vs. 6.5 µm on average), but also because of its irregular outline, which is due to the presence of blocky elements composing the distal shield. Conversely, the outline of small crassus is very smooth.

-

Genus Tubirhabdus Prins ex Rood et al., 1973

-

Type species. Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973

-

Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973

Range. Sinemurian–Tithonian (Bown and Cooper, 1998).

Occurrence. Tubirhabdus patulus is reported to be a an extremely long-ranging species, and it is observed throughout the studied interval.

Remarks. This is a narrowly elliptical coccolith with a central-area structure that supports a broad, hollow spine. Although the holotype dimensions state a coccolith smaller than 4 µm (Rood et al., 1973), the size range of our studied material goes from 2.75 to 7 µm. Three discrete morphotypes of this species were identified in the studied material based upon size and thickness of the rim. Herein, the “thin” and “thick” morphotypes are partly equivalent to the T. patulus “small” (pl. 4.9, figs. 16–17, p. 71) and “large” (pl. 4.9, figs. 18–19, p. 71) illustrated by Bown and Cooper (1998). A third morphotype is represented by tiny coccoliths clearly displaying a tube-like spine in the reduced central area. Kristan-Tollmann (1988b) introduced two subspecies mainly based on the spine shape and dimensions, namely T. patulus patulus (pl. 3, figs. 2–6; pl. 5, fig. 8) and T. patulus tubaformis (pl. 3, figs. 2–4, 7–8). However, the differences in the spine morphology are difficult to observe with LM.

This species is very abundant in the studied section, constituting 22 % of the total coccolith abundance. Moreover, a shift in the proportions occurs from the base to the top of El Matuasto I between thick and thin T. patulus. Further analysis is necessary to elucidate if these morphotypes respond to preservation or ecological factors.

-

Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973 (tiny morphotype)

(Plate 1, fig. 12)

-

1973 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., pp. 373–374, pl. 2, fig. 3.

-

1979 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Medd, p. 45, pl. 9, fig. 9.

-

1982 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Hamilton in Lord, pl. 3.1, fig. 20.

-

1987a Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Bown, pl. 1, figs. 3–4.

-

1987b Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Bown, pp. 18–20, pl. 2, figs. 4–6; pl. 12, figs. 11–12.

-

1988a Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Kristan–Tollmann, pp. 72–73, pl. 1, fig. 1, 5 (top right).

-

1988b Tubirhabdus patulus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973 n. ssp. Kristan–Tollmann, pp. 116–117, pl. 3, figs. 2–6; pl. 5, fig. 8.

-

1992 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Cobianchi, p. 104, fig. 22n.

-

1998 Tubirhabdus patulus Rood et al., 1973. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.1, fig. 13.

-

2013 small Tubirhabdus patulus Rood et al., 1973. Mattioli et al., pl. 1, figs. 1.

Remarks. This morphotype is represented by small coccoliths with a proportionally bigger spine compared to its overall size. It better applies to the holotype diagnosis by Rood et al. (1973, p. 373): “A small species of Tubirhabdus with a very broadly open oval to circular central spine”. The holotype dimensions state a coccolith smaller than 4 µm; accordingly, in this contribution the pictures provided for the synonymy list comprise specimens between 2.75 and 4.6 µm.

-

Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973 (thin morphotype)

(Plate 1, figs. 13–14)

-

1969 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, pl. 1, fig. 10B–C (non fig. 10A) (nomen nudum).

-

1974 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Barnard and Hay, pl. 1, fig. 4.

-

1982 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Hamilton in Lord, pl. 3.1, fig. 16.

-

1995 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Lozar, p. 110, pl. 1, fig. 10.

-

1998 Tubirhabdus patulus Rood et al., 1973. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.1, fig. 14; pl. 4.9, figs. 16–17.

-

2000 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Walsworth-Bell, p. 51, fig. 4.7; p. 90, fig. 6.3.

-

2008 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Aguado et al., fig. 5.35–36.

-

2017 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Peti et al., p. 11, fig. 5Y.

-

2019 Tubirhabdus patulus Rood et al., 1973. Menini et al., pl. 1 (thin).

-

2021 Tubirhabdus patulus Rood et al., 1973. Fraguas et al., fig. 9, CM.255.

Remarks. This morphotype comprises specimens with two central-area dimensions: coccoliths with a broadly open, rectangular central area (Prins, 1969, pl. 1 fig. 10C; Bown, 1987b, pl. 12, figs. 11–12) and specimens with a narrowly elliptical, elongated central area (lozenge-like) (Prins, 1969, pl. 1., fig. 10A). Both are spanned by a median structure that supports a thin, sometimes oval spine, like in the drawing of Prins (1969, pl. 1, fig. 10B).

The coccolith dimensions are usually bigger (5–7 µm) than the holotype description, and the specimens in synonymy are comprised between 4.7 and 6.2 µm.

-

Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973 (thick morphotype)

(Plate 1, figs. 15–16)

-

1969 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, pl. 1, fig. 10A–B (non fig. 10C) (nomen nudum).

-

1982 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Hamilton in Lord, pl. 3.4, fig. 10.

-

?1988 Parhabdolithus leiassicus Deflandre, 1954. Angelozzi, p. 142, pl. 2, fig. 9.

-

1998 Tubirhabdus patulus Rood et al1973. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.9, figs. 18–19.

-

1995 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Lozar, p. 110, pl. 1, figs. 11–12.

-

2006 Tubirhabdus patulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 2, fig. 5.

-

2010 Tubirhabdus patulus Rood et al., 1973. Reggiani et al., pl. 1.16.

-

2019 Tubirhabdus patulus Rood et al., 1973. Menini et al., pl. 1 (thick).

Remarks. Slightly elliptical coccoliths showing a very reduced oval central area infilled by a thick spine. Medd (1979) already stated that the T. patulus proximal view may be confused under the LM with Mitrolithus elegans because in both species the base of a hollow spine is visible. However, the proximal shield architecture is different in the two species. The Tubirhabdus patulus proximal shield is composed of small elements surrounding a broadly open central area, and the foci of the asymmetrical extinction cross are very far away along the major axis of the ellipsis, while the M. elegans proximal shield elements are blocky, making the central opening very reduced, and the foci of the extinction cross are in contact with the base of the hollow spine. Prins (1969) nicely illustrated such features (pl. 1, figs. 10A–11A).

-

Order STEPHANOLITHIALES Bown and Young, 1997

-

Family PARHABDOLITHACEAE Bown, 1987b

-

Genus Crucirhabdus Prins ex Rood et al., 1973

-

Type species. Crucirhabdus primulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973, emend. Bown, 1987b

-

Crucirhabdus primulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973, emend. Bown, 1987b

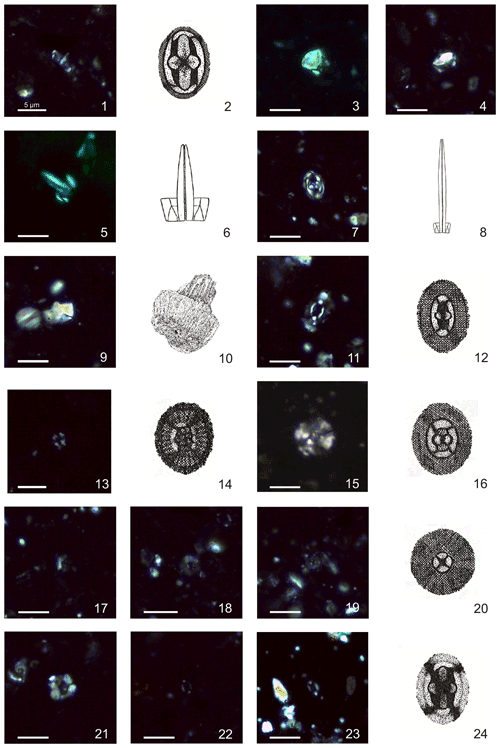

(Plate 2, figs. 1–2)

-

1969 Crucirhabdus primulus var. nanus Prins, p. 551, pl. 1, fig. 1A–B; pl. 2, fig. 1A–B; pl. 3, fig. 1A–B (nomen nudum).

-

1969 Crucirhabdus primulus var. primulus Prins, p. 552, pl. 2, fig. 2A (non fig. 2B); pl. 3, fig. 2A (non fig. 2B) (nomen nudum).

-

1969 Crucirhabdus primulus var. striatulus Prins, p. 554, pl. 3, fig. 3A–B (nomen nudum).

-

1973 Crucirhabdus primulus Prins ex Rood et al., pp. 367–368, pl. 1, figs. 1–2.

-

1979 Apertius dorei Goy in Goy et al., p. 40, pl. 2, fig. 6.

-

1981 Apertius dorei Goy, 1979; Goy, pl. 9, figs. 9–10; pl. 10, figs. 1–3; text-fig. 8.

-

1987b Crucirhabdus primulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973 emend. Bown, pp. 23–24, pl. 2, figs. 15–18; pl. 3, figs. 1–3; pl. 12, figs. 17–20; text-fig. 10.

-

1998 Crucirhabdus primulus Rood et al., 1973. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.2, figs. 9–11; pl. 4.10, figs. 14–15.

-

2000 Crucirhabdus primulus Rood et al., 1973. Walsworth-Bell, p. 51, fig. 4.7; p. 90, fig. 6.3.

-

2010 Crucirhabdus primulus Rood et al., 1973. Reggiani et al., pl. 1., fig. 2.

-

2013 Crucirhabdus primulus Rood et al., 1973. Mattioli et al., pl. 1, fig. 16.

-

2019 Crucirhabdus primulus Rood et al., 1973. Menini et al., pl. 1.

-

2019 Crucirhabdus primulus Rood et al., 1973. Ferreira et al., pl. 1.

Plate 2Calcareous nannofossils from El Matuasto I, Los Molles Formation, Neuquén Basin. All pictures from LM under crossed nicols and distal view unless specified. Scale bar: 5 µm. Illustrations adapted after Prins (1969) except fig. 10 after Noël (1965b). (1, 2) Crucirhabdus primulus Prins, 1969 ex Rood et al., 1973 emend. Bown, 1987b, side and distal view, EM-I-19 (YT.RMP_N.000012.11). (3) Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954, side view, EM-I-1 (YT.RMP_N.000012.1). (4) Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b, side view, EM-I-13 (YT.RMP_N.000012.6). (5, 6) Parhabdolithus liasicus spp. distinctus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b, side view, EM-I-15 (YT.RMP_N.000012.8). (7, 8) Parhabdolithus liasicus spp. liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b, distal and side view, EM-I-12 (YT.RMP_N.000012.5). (9, 10) Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, 1965b, side view, EM-I-18 (YT.RMP_N.000012.10). (11, 12) Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b, EM-I-16 (YT.RMP_N.000012.9). (13, 14) Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993, EM-I-23 (YT.RMP_N.000012.13). (15, 16) large Similiscutum aff. finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993, EM-I-26 (YT.RMP_N.000012.16). (17, 20) Similiscutum cruciulus group, EM-I-18 (YT.RMP_N.000012.10). (21) Calyculus sp. Noël, 1972, EM-I-16 (YT.RMP_N.000012.9). (22) Lotharingius barozii Noël, 1972, early morphotype, EM-I-19 (YT.RMP_N.000012.11). (23, 24) Lotharingius barozii Noël, 1972, typical morphotype, EM-I-23 (YT.RMP_N.000012.13).

Range. Norian–Toarcian (Bown and Cooper, 1998).

Occurrence. This species is a characteristic north-western Europe component (boreal realm; Bown, 1987b) and tends to be scarce in Tethyan localities during the Early Jurassic (Bown, 1987b; Fraguas et al., 2018). In El Matuasto I, this species was recorded consistently from the base to the top of the section (NJT4a–c zones).

Remarks. In the present study C. primulus is widely recognized in side view under the LM and differs from Parhabdolithus liasicus by having a low rim that gives it a “flat” appearance. The proximal shield appears as two tooth-like elements which are very far away each other because of the presence of a widely open central area. The presence or absence of the spine depends on the preservation quality. Small specimens resembling the variety C. primulus nanus described in Prins (1969) were sporadically observed. The recognition of C. primulus in distal view could be difficult because the delicate cross-structure may be easily broken.

-

Genus Mitrolithus Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954 emend. Bown and Young in Young et al., 1986

-

Type species. Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954

-

Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954

(Plate 2, fig. 3)

-

1954 Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, p. 148, pl. 15, figs. 9–11; text-figs. 66–67.

-

1965 Alvearium dorsetense Black, pp. 133, 136, fig. 5.

-

1986 Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Young et al., pl., figs. I, L.

-

1987b Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Bown, pp. 26–27, pl. 3, figs. 6–15; pl. 12, figs. 23–28.

-

1988b Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Kristan–Tollmann, p. 114, pl. 1, figs. 6–7.

-

1998 Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.2, figs. 13–14; pl. 4.10, figs. 18–20.

-

2000 Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Walsworth-Bell, p. 51, fig. 4.7; p. 90, fig. 6.3.

-

2008 Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Fraguas et al., pl. 1, fig. 4.

-

2010 Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Reggiani et al., pp. 2–3, pl. 1., fig. 13.

-

2013 Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Mattioli et al., pl. 1, fig. 13.

-

2017 Mitrolithus elegans Deflandre, 1954. Peti et al., p. 11, fig. 5F.

Range. Hettangian–Pliensbachian (Bown and Cooper, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999).

Occurrence. This species is a typical component of Tethys and north-eastern Pacific assemblages (Bown, 1987b, 1992; Bown and Lord, 1990; Ferreira et al., 2019) and is rarely observed in north-western European associations during the lower Sinemurian to the lower Toarcian (Bown 1987b, 1992; Mattioli and Erba, 1999). In the El Matuasto I section, we found the first record of common and consistent occurrence of M. elegans in the south-eastern Pacific area in the early Pliensbachian.

Remarks. Mitrolithus species, and especially M. elegans, can be observed in both plan view (proximal or distal) and side view, which is more diagnostic. In this study, Mitrolithus elegans was usually observed in side view, having a prominent spine protruding from the distal shield of the coccolith. Specimens observed in proximal view were also common. Isolated spines (corresponding to the A. dorsetensis of Black, 1969) were rarely observed. The holotype dimensions are 5.8 µm length and 6 µm height (Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, 1954). Differences between M. elegans and T. patulus have been discussed above.

-

Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b

(Plate 2, fig. 4)

-

1987b Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, pp. 28–30, pl. 4, figs. 4–7; pl. 12, figs. 29–30.

-

1988b Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b. Kristan–Tollmann, p. 115, pl. 1, figs. 3–5.

-

non 1992 Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b. Cobianchi, fig. 20n.

-

1998 Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.2, figs. 17–18; pl. 4.10, figs. 24–25.

-

2010 Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b. Reggiani et al., pp. 2–3, pl. 1, figs. 14–15.

-

2013 Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b. Mattioli et al., pl. 1, fig. 9–10.

-

? 2015 Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b. Casellato and Erba, pl. 1.25.

-

2019 Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b. Menini et al., pl. 1.

Range. Sinemurian–Pliensbachian (Mattioli and Erba, 1999).

Occurrence. M. lenticularis occurs consistently and abundantly in El Matuasto I from the base of the section, dated as early Pliensbachian (NJT4 biozone). Angelozzi and Pérez Panera (2016) noticed that this species is characteristic of the Pliensbachian–Toarcian boundary assemblages in the Neuquén Basin. Bown (1987b, 1992) and Bown and Cooper (1998) considered M. lenticularis a typical Tethyan species. Its presence in the Neuquén Basin is crucial to establish palaeobiogeographic relationships between the south-eastern Pacific and the Tethys realms.

Remarks. Mitrolithus lenticularis, which is usually recognized in side view, differs from M. elegans because of its slightly smaller size (Holotype dimensions are 4.5 µm length, 3.7 µm height; Bown, 1987b) and because it has a lenticular spine that does not protrude from the rim.

-

Genus Parhabdolithus Deflandre in Grassé, 1952 emend. Bown, 1987b

-

Type species. Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre in Grassé, 1952

-

Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre in Grassé, 1952

Range. Hettangian–Toarcian (Bown and Cooper, 1998).

Remarks. This taxon has a high rim and a transverse bar supporting a spine in the central area. Owing to spine dimorphism, an informal separation within the species was recognized by Prins (1969). Bown (1987b) proposed two subspecies based on previous descriptions and illustrations by Deflandre (1952; in Deflandre and Fert, 1954). Parhabdolithus liasicus distinctus has a larger rim and a relatively thick spine compared to P. liasicus liasicus, which is a tiny coccolith with an extremely long and thin spine. Both subspecies are consistently present throughout the El Matuasto I section, even though P. liasicus distinctus abundance is much higher (88 %) than P. liasicus liasicus (12 %).

-

Parhabdolithus liasicus distinctus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b

(Plate 4, figs. 5–6)

-

1952 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre in Grassé, p. 466, text-fig. 362 (J, L, M, non K).

-

1954 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre; Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, p. 162, text-figs. 105–108 (non 104).

-

1965b Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1954. Noël, pl. 3, fig. 7; pl. 4, fig. 7; text-fig. 22a–b, e.

-

1969 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1954. Prins pl. 2, figs. 4A–B.

-

1969 Crucirhabdus primulus var. primulus Prins, p. 552, pl. 2, fig. 2B (non fig. 2A); pl. 3, fig. 2B (non fig. 2A) (nomen nudum).

-

1973 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1952. Rood et al., pp. 372–373, pl. 2, fig. 1.

-

1973 Crepidolithus cavus Prins ex Rood et al., p. 375, pl. 2, fig. 5.

-

1977 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1952. Hamilton, pl. 4, fig. 7.

-

1979 Parhabdolithus marthae Deflandre, 1954. Medd, pl. 1, fig. 10.

-

1982 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1952. Hamilton in Lord, pl. 3.1, fig. 5; pl. 3.4, figs. 3–4.

-

1987b Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1952. Crux, pl. 1, figs. 14–16; pl. 1, fig. 10.

-

1987b Parhabdolithus liasicus distinctus Deflandre, 1952. Bown, pp. 30–31, pl. 4, figs. 10–15; pl. 13, figs. 5–8.

-

1992 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1954. Baldanza and Mattioli, pl. 1, fig. 9.

-

1992 Parhabdolithus liasicus distinctus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Cobianchi, p. 98, fig. 21a–b.

-

1998 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre in Grasse, 1952 ssp. distinctus Bown, 1987b. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.2, figs. 19–20; pl. 4.10, figs. 26–29.

-

2000 Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Walsworth-Bell, p. 51, fig. 4.7; p. 90, fig. 6.3.

-

2006 Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 2, fig. 15.

-

2008 Parhabdolithus liasicus distinctus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Fraguas et al., pl. 1, fig. 3.

-

2013 Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Mattioli et al., pl. 1, figs. 3–6, 8.

-

non 2013 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1954. Rai and Jain, pl. 1, fig. 10a–c.

-

2017 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1952. Peti et al., figs. S.1 6-11 (non 7; appendix F).

-

2019 Parhabdolithus liasicus distinctus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Ferreira et al., pl. 2.

Remarks. Parhabdolithus liasicus distinctus is usually observed in side view, showing a high rim with a slightly thin, tapering spine that is double the height of the rim. The coccolith length dimensions provided by Bown (1987b, p. 30) are 3.7–6.8 µm and in our specimens range from 4 to 6 µm. They are often strongly overgrown. In distal view, the base of the spine provides an extinction pattern with a clover-like structure aligned with the minor axis of the ellipse.

-

Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b

(Plate 2, figs. 7–8)

-

1952 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre in Grassé, text-fig. 362K.

-

1954 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre in Grassé; Deflandre in Deflandre and Fert, text-fig. 104; pl. 15, figs. 28–31.

-

1965b Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre in Grassé, 1952. Noël, pl. 4, figs. 3–4; text-fig. 22c.

-

1969 Parhabdolithus longispinus Prins pl. 2, fig. 5 (nomen nudum).

-

1987b Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus Deflandre in Grassé, 1952. Bown, p. 31, pl. 4, figs. 16–17; pl. 13, figs. 9–10.

-

1998 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre in Grassé, 1952 ssp. liasicus. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.3, fig. 1; pl. 4.10, figs. 30–31.

-

non 2006 Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 2, fig. 15.

-

2013 Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Mattioli et al., pl. 1, figs. 7, 11–12.

-

2017 Parhabdolithus liasicus Deflandre, 1952. Peti et al., fig. S.1 7 (appendix F).

-

2017 Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Peti et al., figs. S.1 12–13 (appendix F).

-

2019 Parhabdolithus liasicus liasicus (Deflandre, 1952) Bown, 1987b. Ferreira et al., pl. 2.

Remarks. In this latter morphotype, the rim dimensions are very small, while the spine is thin and very long; the spine is often broken. Dimensions given by Bown (1987b) are 2.8–3.6 µm length and 1.6–2 µm width. The extinction pattern of the spine in plan view forms a central cross showing a butterfly-like structure aligned with the minor axis of the ellipse.

-

Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, 1965b

(Plate 2, figs. 9–10)

-

1965b Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, pp. 95–96, pl. 4, figs. 1–2, text-fig. 24.

-

1987b Parhabdolithus zweilii Crux, p. 95; pl. 1, figs. 1–4.

-

1987a Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, 1965b. Bown, p. 43, pl. 1, figs. 5–6; pl. 2, figs. 8–9.

-

1987b Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, 1965b. Bown, p. 34, pl. 5, figs. 3–6; pl. 13, figs. 15–16.

-

1992 Mitrolithus lenticularis Bown, 1987b. Cobianchi, p. 98, fig. 20n.

-

1998 Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, 1965b. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.3, figs. 3–4; pl. 4.11, fig. 3.

-

2013 Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, 1965b. Mattioli et al., pl. 1., fig. 2.

-

2017 Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, 1965b. Peti et al., p. 11, fig. 5C.

-

2019 Parhabdolithus robustus Noël, 1965b. Ferreira et al., p. 8, pl. 2.

Range. Sinemurian–Pliensbachian (Bown and Cooper, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999; Ferreira et al., 2019).

Occurrence. Parhabdolithus robustus was herein recorded for the first time in the south-eastern Pacific, with a consistent and relatively abundant occurrence from the early to late Pliensbachian (NJT4 a to c subzones). The species is common in the Early Jurassic assemblages from Tethys and boreal realms (Bown, 1987a, b, 1992; Bown and Cooper, 1998), especially abundant in Timor (Bown, 1987b) and rare in the north-eastern Pacific during the Pliensbachian (Bown, 1992). The different relative abundance of this species in the north-eastern and south-eastern Pacific would suggest a possible ecological factor. The LO of P. robustus is recorded in the early Pliensbachian within the NJT4a subzone (Bown and Cooper, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999), while in Argentina its presence is observed at least until the NJT4c subzone according to the zonation of Ferreira et al. (2019).

Remarks. This coccolith is mainly observed in side view. It possesses a thick, high rim, which gives it a distinctive blocky appearance and a short, broad spine ending at or just above the rim.

-

Order PODORHABDALES Rood et al., 1971 emend. Bown, 1987b

-

Family BISCUTACEAE Black, 1971

-

Genus Biscutum Black in Black and Barnes, 1959

-

Type species. Biscutum testudinarium Black in Black and Barnes, 1959

-

Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b

(Plate 2, figs. 11–12)

-

1969 Palaeopontosphaera binodosa Prins, pl. 2, fig. 12 (nomen nudum).

-

1987b Biscutum grandis Bown, pp. 44–45, pl. 6, figs. 4–6; pl. 13, figs. 23–25; text-fig. 11.

-

1998 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.4, fig. 14; pl. 4.12, figs. 15–16.

-

2004 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Mattioli et al., fig. 4E.

-

2006 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 1., figs. 3–4.

-

2007a Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 5D.

-

2007b Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 1.

-

2008 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Fraguas et al., pl. 1, fig. 9.

-

2010 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Reggiani et al., pp. 6–7, pl. 2., figs. 27–28.

-

2016 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Rai et al., fig. 3.14a–b.

-

2017 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Peti et al., figs. S.3 5–8 (appendix F).

-

2019 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Menini et al., pl. 2. (SN3.57 and LAL18)

-

2019 Biscutum grande Bown, 1987b. Ferreira et al., pl. 1 (Peniche97 and Peniche102.1).

Range. Pliensbachian–Toarcian (Bown and Cooper, 1998).

Occurrence. The consistent presence of this taxon throughout our section and its biostratigraphic reliability allow an accurate age for the sedimentary succession. The FO defines the base of the NJ5 zone (Bown, 1992) and NJ5b (Bown and Cooper, 1998) and NJT4b subzones (Mattioli and Erba, 1999; Ferreira et al., 2019), correlating with the Ibex–Davoei SAZ boundary. Biscutum grande is a species with Tethyan affinities according to Bown (1987b, 1992). Its abundance in the studied samples provide evidence of biogeographic similarities between the south-eastern Pacific and Tethyan assemblages.

Remarks. Biscutum grande is a large, broadly elliptical coccolith composed of a distal shield formed by radial elements and bearing an inner tube cycle. The central area is large, vacant, and sometimes spanned by a thin bar (Bown, 1987b). Under LM, the distal and proximal shields look dark grey, while the inner tube cycle appears as a conspicuously bright rim surrounding the wide central area (Mattioli et al., 2013). The delicate bar is aligned with the minor axis of the elliptic central area, but frequently it is missing; its insertions in the inner tube cycle are, however, seen as two bright lobes. In some cases, the central area can be filled with small calcite crystals (Menini et al., 2019; pl. 2, LAL18) or (very rarely) spanned by a cross (Ferreira et al., 2019; pl. 1, Peniche97). According to de Kaenel and Bergen (1993) Palaeopontosphaera binodosa Prins, 1969, is a synonym of Similiscutum finchii; herein we consider P. binodosa to be a synonym of B. grande.

-

Genus Similiscutum de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993

-

Type species. Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993

-

Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993 group Mattioli et al. 2004

(Plate 2, figs. 17–20)

-

1969 Palaeopontosphaera repleta Prins, pl. 2, fig. 11 (nomen nudum).

-

1977 Calyculus cribrum (Noël 1972) Hamilton, p. 586, pl. 1, fig. 9.

-

1986 Biscutum sp. Young et al., p. 124, plate, fig. F.

-

1987b Biscutum dubium (Noël 1965) Grün in Grün et al. 1974, Crux, p. 89, pl. 2, figs. 4–7.

-

1990 Biscutum novum (Goy 1979) Bown 1987a, Cobianchi, p. 134, fig. 4b.

-

1990 Biscutum aff. novum (Goy 1979) Bown 1987a, Cobianchi, p. 134 and 136, fig. 4c.

-

1992 Biscutum novum (Goy 1979) Bown 1987a, Cobianchi (partim) pp. 92–93, fig. 19b (non fig. 19c, d).

-

1992 Biscutum aff. B. novum (Goy 1979) Bown 1987a, Cobianchi (partim) p. 93, fig. 19e (non fig. 118).

-

1993 Similiscutum avitum de Kaenel and Bergen, pp. 874–875, pl. 1, figs. 12–14; pl. 2, figs. 1–4.

-

1993 Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, pp. 875–876, pl. 2, figs. 5–11.

-

1993 Similiscutum orbiculus de Kaenel and Bergen, pp. 873–874, pl. 1, figs. 1–11.

-

1998 Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.5, figs. 3–4; pl. 4.12, figs. 28–30.

-

2000 Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Walsworth-Bell, p. 51, fig. 4.7.

-

2004 Similiscutum avitum de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Mattioli et al., p. 9, fig. 4b.

-

2004 Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Mattioli et al., p. 9, fig. 4a.

-

2004 Similiscutum orbiculus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Mattioli et al., p. 9, fig. 4c.

-

2006 Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 2, fig. 1.

-

2006 Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 2, fig. 2

-

2007a Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 6O.

-

2007a Similiscutum orbiculus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 6N.

-

2007b Similiscutum orbiculus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 2.

-

2007b Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 2.

-

2010 Similiscutum cruciulus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Reggiani et al., pp. 6–7, pl. 2, figs. 29–30.

-

2019 Similiscutum orbiculus de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Menini et al., p. 17, pl. 2 (S. cruciulus orbiculus).

-

2021 Similiscutum avitum de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Fraguas et al., fig. 9, CM.235.1.

Range. Pliensbachian–Toarcian (de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993; Bown and Cooper, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999).

Occurrence. The presence of the group in this section constitutes the first record in the Early Jurassic for the Neuquén Basin and the second for the south-eastern Pacific Ocean (Fantasia et al., 2018). Similiscutum cruciulus is commonly used to define the base of the NJT4 biozone (Bown and Cooper, 1998; Mattioli and Erba, 1999). Due to the clustering criteria and the similar stratigraphic interval (Mattioli et al., 2004), the FO of the S. cruciulus group is proposed to define the base of the NJT4 biozone (Ferreira et al., 2019) within the early Pliensbachian and corresponding to the Jamesoni SAZ.

Remarks. This group includes S. orbiculus, S. avitum, and S. cruciulus (i.e. small, normal to slightly elliptical coccoliths, with a homogeneously grey unicyclic distal shield and a light grey “collar” surrounding the central area). The three species introduced by de Kaenel and Bergen (1993) are roughly differentiated because S. avitum shows a broadly elliptical coccolith, S. orbiculus has a subcircular outline, and both have a vacant reduced central area, while S. cruciulus shows a subcircular outline with a cross spanning the central area. Nevertheless, Mattioli et al. (2004) proposed a clustering for the Similiscutum cruciulus group based on the absence of diagnostic biometric differences between the species, highlighting the morphological plasticity within the genus Similiscutum.

-

Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993

(Plate 2, figs. 13–14)

-

1969 Striatococcus grandiculus Prins, pl. 2, fig. 14 (nomen nudum).

-

non 1969 Palaeopontosphaera binodosa Prins, pl. 2, fig. 12 (nomen nudum).

-

1984 Biscutum finchii Crux, p. 168, fig. 9 (3, 4), fig. 13.5.

-

1987a Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, p. 44, pl. 2, figs. 3–4, 10–11.

-

1987b Biscutum novum (Goy 1979) Bown 1987a. Bown, p. 77, pl. 13, figs. 19–20.

-

1987b Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a. Bown (partim), pp. 42–44, pl. 5, fig. 18; pl. 6, figs. 1–3; (non pl. 13, figs. 21–22); text-fig. 11.

-

1992 Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a. Baldanza and Mattioli, pl. 1, fig. 12.

-

1992 Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a. Cobianchi, p. 92, fig. 19f–g; text-fig. 18.

-

1992 Biscutum aff. B. finchii Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a. Cobianchi, p. 92, fig. 19i; text-fig. 18.

-

1992 Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a. Reale et al., pl. 1, figs. 5–6.

-

1993 Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, pp. 877–878, pl. 3, figs. 11–13.

-

1997 Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984. Picotti and Cobianchi, pl. 2, fig. 1.

-

1998 Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984. Bown and Cooper in Bown, pl. 4.4, fig. 13; pl. 4.12, figs. 11–14.

-

non 1998 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987a. Parisi et al., pl. 4, fig. 7

-

1999 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987a. Mattioli and Erba, p. 365, pl. 1, figs. 19–20.

-

2002 Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984. Perilli and Comas-Rengifo, pl. 1, fig. 13.

-

2004 Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Mattioli et al., p. 25, fig. 4j.

-

2006 Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Mailliot, pl. 2, figs. 1–4.

-

2006 Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Mailliot et al., pl. 1.

-

non 2006 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987a. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 1, figs. 7–8.

-

2006 Biscutum novum (Goy 1979) Bown, 1987. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 2, figs. 17.

-

2007a Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987a. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 5E–F.

-

2007b Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987a. Veiga de Oliveira et al., fig. 1.

-

non 2008 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987b. Fraguas et al., pl. 1, fig. 10.

-

non 2013 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987b. Rai and Jain, pl. 1, figs. 2a–d; pl. 3, figs. 1a–b.

-

2019 Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Mattioli et al., 2004. Menini et al., p. 17, pl. 2 (SN2.20, LAL18).

-

2019 Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Mattioli et al., 2004. Ferreira et al., pl. 2 (Peniche12).

-

2021 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987a. Fraguas et al., fig. 9, CM.235.2.

Range. Pliensbachian–Toarcian (Bown and Cooper, 1998).

Occurrence. The presence of S. finchii in the studied section is observed within the NJT4c subzone. Mattioli et al. (2013) indicate that the FO of this species marks the boundary between the NJ4a and NJ4b subzones within the Margaritatus SAZ. This event matches the record of Angelozzi and Pérez Panera (2016) within the equivalent Fanninoceras fannini NAZ. According to Riccardi (2008b) the F. fannini NAZ correlates with the upper part of the Davoei and most of the Margaritatus SAZ of the western Tethys. In Ferreira et al. (2019), the FO of S. finchii occurs simultaneously with the FO of Lotharingius barozii, and this latter event marks the base of the NJT4c subzone within the Davoei SAZ (late Pliensbachian) in Portugal. Thus, the record of the FO of Similiscutum finchii seems to be quite consistent between Argentina and Portugal.

Remarks. Under the LM, Similiscutum finchii appears as a medium-sized, normal to broadly elliptical coccolith. The distal shield is light grey with an irregular outline. The central area is narrow, elongated, and sub-rectangular in shape. In SEM pictures (like the holotype), the central area is ogive-shaped, elongated, and narrowly elliptical. Biometrics of S. finchii (on average 4.53 µm for the major axis and 3.76 µm for the minor axis; Mattioli et al., 2004) fall at the small end of the range of sizes reported in the literature (Crux, 1984: 5.4–6.6 µm; Bown, 1987b: 5.8–8.5 µm). Morphologically and biometrically, S. finchii is quite similar to S. novum (average 4.13 µm for the major axis and 3.48 µm for the minor axis; Mattioli et al., 2004), which is, however, overall smaller in size, less elliptical, and with a less developed central area. In the literature, specimens are figured which are larger, more broadly elliptical, and with a more reduced length of the central area than the S. finchii holotype description. Such specimens are described here as large Similiscutum aff. finchii and were designated as S. giganteum in Ferreira et al. (2019). De Kaenel and Bergen (1993) considered Palaeopontosphaera binodosa Prins, 1969, to be a synonym of S. finchii, but we consider P. binodosa to be a synonym of Biscutum grande. In fact, the drawing in pl. 2, fig. 12 of Prins (1969) shows the presence of a widely open central area spanned by a bridge whose insertions are clearly visible in the inner rim of the coccolith.

-

Large Similiscutum aff. finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993

(Plate 2, figs. 15–16)

-

1969 Palaeopontosphaera crucifera Prins, pl. 2, fig. 10 (nomen nudum).

-

1969 Palaeopontosphaera veterna Prins, pl. 2, fig. 9 (nomen nudum).

-

1987b Biscutum finchii Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a. Bown (partim), pl. 13, figs. 21–22).

-

1998 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Bown and Cooper, pl. 4.12, figs. 13–14 (large morphotype).

-

2002 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Perilli and Comas–Rengifo, pl. 1, fig. 12.

-

2006 Similiscutum giganteum Mailliot, p. 234, pl. 1, figs. 1–6. (nomen nudum)

-

2006 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987b. Perilli and Duarte, pl. 1, figs. 7–8.

-

2008 Biscutum finchii (Crux, 1984) Bown, 1987b. Fraguas et al., pl. 1, fig. 10.

-

2014 Similiscutum giganteum Mailliot, 2006. Reolid et al., fig. 6. (nomen nudum)

-

2016 Similiscutum giganteum Mailliot, 2006. Da Rocha et al., fig. 7.9–10. (nomen nudum)

-

2019 Similiscutum aff. S. finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Menini et al., pl. 2 (large, SN3.57B)

-

2019 Similiscutum finchii (Crux, 1984 emend. Bown, 1987a) de Kaenel and Bergen, 1993. Ferreira et al., fig. 2. (nomen nudum).

Range. Late Pliensbachian–late Toarcian (Bown, 1987b; Mailliot, 2006; Ferreira et al., 2019).