the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Two new clavate Fragilariopsis and one new Rouxia diatom species with biostratigraphic and paleoenvironmental applications for the Pliocene-Pleistocene, East Antarctica

Grace Duke

Josie Frazer

Briar Taylor-Silva

Christina Riesselman

Three new pennate diatom taxa, Fragilariopsis clava sp. nov. Duke; Fragilariopsis armandae sp. nov. Frazer, Duke et Riesselman; and Rouxia raggattensis sp. nov. Duke et Riesselman, are described and named from Pliocene-Pleistocene sediments collected from the continental rise adjacent to the Wilkes Land coast of East Antarctica. The stratigraphic occurrence of F. clava and F. armandae at IODP Site U1361 are well-constrained to Marine Isotope Stages G9-G7 (2.76–2.74 Ma) and 101–97 (2.58–2.47 Ma), respectively. The short stratigraphic ranges of F. clava and F. armandae are potentially useful biostratigraphic markers for constraining the age of late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene Antarctic sediments. Rouxia raggattensis is observed in the oldest sample examined at Site U1361 from ∼4.05 Ma and is more common between 3.0–2.15 Ma. The rise in abundance of R. raggattensis corresponds to a large turnover in diatom species between 3 and 2 Ma associated with Antarctic cooling, suggesting that sea surface conditions were favorable for R. raggattensis during this dynamic time. Clavate Fragilariopsis species diversified between 2.9–2.7 Ma, but some species quickly went extinct between 2.7–2.5 Ma, possibly because they were marginalized by the cooler climate conditions.

- Article

(17262 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(390 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Documenting the diatom assemblage of the Southern Ocean during the Pliocene and Pleistocene provides a proxy for past environmental conditions and stratigraphic age datums (e.g., Bertram et al., 2018; Taylor-Silva and Riesselman, 2018; McKay et al., 2012; Armbrecht et al., 2018; Barron, 1996; Konfirst and Scherer, 2012; Cortese and Gersonde, 2008). Environmental preferences of fossil taxa are based on the study of extant species, with the assumption that their preferences have remained constant through time (Armand et al., 2005; Crosta et al., 2005, 1998; Romero et al., 2005), and their co-occurrence with other taxa and environmental proxies (e.g., Winter et al., 2010). Cosmopolitan diatom species are not useful environmental indicators but can be excellent age indicators if they are well preserved and have well-constrained first and last stratigraphic appearances. Early literature synthesized the first and last appearances of diatom species relative to paleomagnetic reversals and other chronostratigraphic constraints to create diatom zones, establishing a framework to determine the relative ages of sedimentary sequences (e.g., Ciesielski, 1983; Harwood and Maruyama, 1992; Gersonde and Burckle, 1990; McCollum, 1975; Schrader, 1976). Later work refined the sequence of biostratigraphic events and reconciled published ages to create a more robust biochronology that is applicable across multiple Southern Ocean sites (Cody et al., 2008, 2012; Crampton et al., 2016).

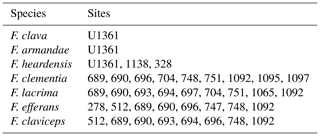

Table 1Valve measurements of Fragilariopsis clava sp. nov., Fragilariopsis armandae, and other clavate Fragilariopsis taxa.

a Combination of specimens from U1361A and five specimens measured from Plate 2 (Figs. 1, 4–7) of Bohaty et al. (2003). b Reclassified specimens from Bohaty et al. (2003) Plate 2 (Figs. 2–3) and Plate 3 (Fig. 9), originally classified as F. heardensis. c Three specimens from Plate 8 (Fig. 19) of Gombos (1976) and Plate 2 (Figs. 11–10) of Bohaty et al. (2003). d Five specimens measured from Plate 2 (Figs. 1, 3, 5, 6) of Schrader (1976) and Plate 2 (Fig. 9) of Gersonde and Burkle (1990). F. lacrima and F. clementia data are from Gersonde (1989), and F. efferans and F. claviceps data are from Schrader (1976).

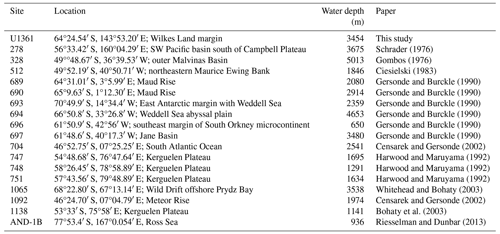

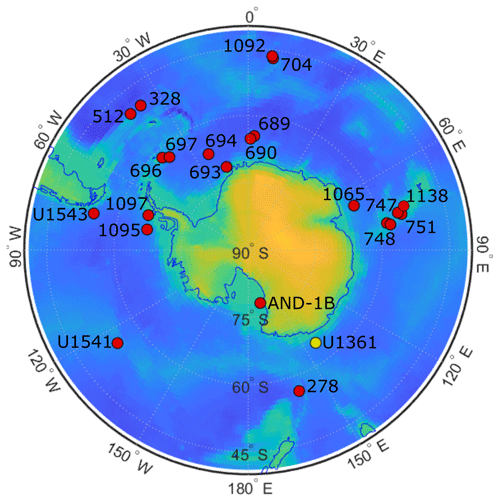

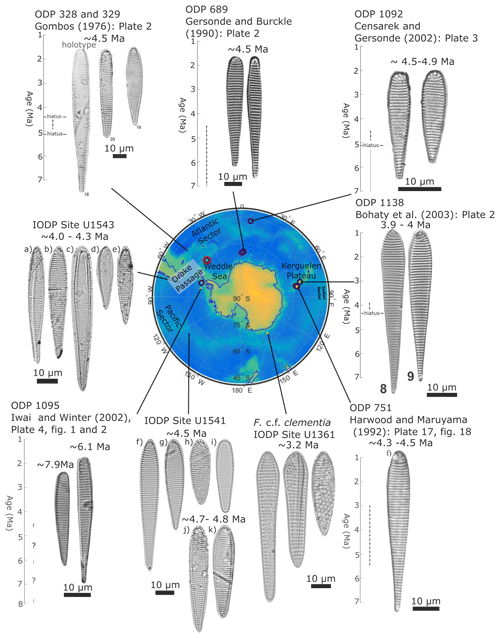

Figure 1ODP and IODP site locations. Map of Antarctica shows the location of Southern Ocean sites that document the presence of clavate Fragilariopsis species (red dots). Site U1361 is distinguished with a yellow dot. Further detail about each site is given in Appendix A Table A2.

Here, we propose three new Southern Ocean diatom taxa, Fragilariopsis clava Duke; Fragilariopsis armandae Frazer, Duke et Riesselman; and Rouxia raggattensis Duke et Riesselman, all of which are useful as environmental indicators and biostratigraphic datums. Fragilariopsis clava and F. armandae appear briefly between 2.76–2.75 Ma (55.59–55.30 m b.s.f.) and 2.58–2.47 Ma (49.57–47.13 m b.s.f.), respectively, at IODP Site U1361 on the Wilkes Land continental rise, East Antarctica, and have not previously been identified in Antarctic sediments. Fragilariopsis clava and F. armandae succeed a lineage of Pliocene clavate diatoms, bolstering the biostratigraphic capability of this suite of species. Rouxia raggattensis was first documented as Rouxia sp. A by Harwood and Maruyama (1992) in Pliocene sediments from Site 751 on the Kerguelen Plateau and subsequently identified in Plio-Pleistocene sediments from ANDRILL Site AND-1B, south of Ross Island on the Ross Sea continental shelf (Riesselman and Dunbar, 2013; Scherer et al., 2007). However, the species could not be formally described from either of these locations due to low abundance and the rarity of complete specimens. Because R. raggattensis is common and well-preserved at Site U1361, it is now possible to fully characterize the species and speculate about its environmental affinities.

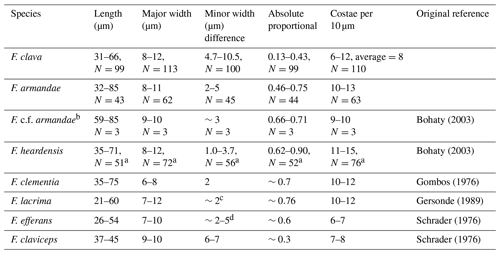

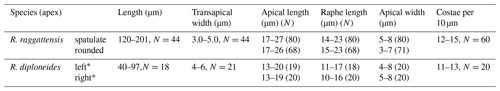

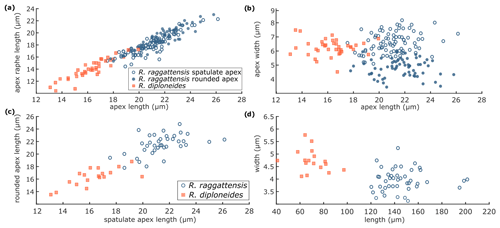

Table 2Rouxia raggattensis and R. diploneides morphometric measurements.

* The apices for a R. diploneides specimen were arbitrarily denoted as “left” and “right” based on its orientation in a field of view because, unlike R. raggattensis, there is no distinction between apices. The morphometric measurements for the “left” and “right” apices remain separate to emphasize they are comparable.

2.1 U1361A sediment samples

Sample material was collected during IODP Expedition 318 in 2010 from Site U1361 (64.45° S, 143.90° E) at 3454 m water depth (Escutia et al., 2011). The site is located on a levee along the continental rise of Wilkes Land, an area of the East Antarctic margin that is currently influenced by winter sea ice and Antarctic Bottom Water formation (Fig. 1). The Wilkes Land margin is of interest because the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is grounded below sea level in the adjacent Wilkes Subglacial Basin, rendering it susceptible to the impact of relatively warm waters intruding onto the continental shelf (Cook et al., 2013; Bertram et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2018). Sediment was sampled at approximately 10 cm resolution from 90.64–29.54 m b.s.f., and lithologies range from varied-colored clay to greenish-gray diatom-rich or -bearing silty clay (Escutia et al., 2011). The interval is dated to approximately 3.9–1.7 Ma based on biostratigraphic datums, and paleomagnetic reversal stratigraphy is used to date an iceberg-rafted debris mass accumulation record (Escutia et al., 2011; Patterson et al., 2014; Tauxe et al., 2012).

2.2 Expedition 383 samples

To support the comparison of our new taxa to established Fragilariopsis species, F. clementia is discussed in Sect. 4.1 (Fig. 14). New light micrographs of F. clementia were produced from IODP sites U1541 and U1543 material to provide example specimens from the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean. Sites U1541 (54.28° S, 125.47° W) and U1543 (54.59° S, 76.73° W) were drilled during Expedition 383 in 2019 at 3604 m water depth on the East Pacific Rise (Winckler et al., 2021a) and 3860 m water depth about 110 nmi southwest of the Chile coast (Lamy et al., 2021), respectively. Two slides from Site U1541C core 11 were examined for F. clementia: U1541C-11H3 20–21 cm and U1541C-11H5 20–21 cm. Micrographs from Site U1543A core 23 were made from four slides: U1543A-23H4 120 cm, U1543A-23H5 120 cm, U1543A-23H6 120 cm, and U1543A-23HCC 18–24 cm. These slides were prepared aboard the JOIDES Resolution during Expedition 383 following the smear slide procedure outlined in Winckler et al. (2021b). The approximate ages of specimens in Fig. 14 are based on the age models from Winckler et al. (2021a) and Lamy et al. (2021).

2.3 Diatom analysis

The new taxa were characterized using light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. For diatom assemblage analysis with light microscopy, quantitative settled slides were prepared following the method of Warnock and Scherer (2014). For each slide, 35–50 µg of bulk sediment was weighed for samples with high biogenic silica (>15 wt % BSi) and 60–70 µg for samples with low biogenic silica. The weighed sediment was placed in a glass test tube with 2 mL of 10 % hydrogen peroxide and two drops of saturated sodium hexametaphosphate and left for a minimum of 8 h in a 40 °C oven.

Duplicate slides were prepared by affixing two 22×40 mm glass cover slips to a clean glass microscope slide with a drop of rubber cement and placing them on a PLEXIGLAS platform approximately 2 cm above the outlet of a 2 L square B-Ker2 settling chamber, partially filled with Elix pure water. Once the slide with cover slips was positioned, the water in the settling chamber was topped up to 2 L and gently agitated. A drop of Kodak Photo-Flo surfactant dispersing agent was added to the sample tube before the sample slurry was dispersed into the chamber. The sample settled out of the water column for a minimum of 6 h before the valve was opened, allowing the water to drain at ∼2 drops per second overnight. Next, the slide and attached cover slips were removed from the chamber and allowed to dry, after which each cover slip was removed from the rubber cement and mounted sediment-side-down on a fresh glass slide using a few drops of Norland Optical Adhesive #61 (refractive index =1.56).

Fragilariopsis clava and Fragilariopsis armandae were counted on an Olympus BX41 microscope with a 10x eyepiece using a 60x objective. Rouxia raggattensis in samples 56.53–29.54 m b.s.f. was counted using the same microscope configuration as for the Fragilariopsis counts, while samples from 84.94–56.53 m b.s.f. were counted on an Olympus BX41 microscope with a 10x eyepiece using a 63x objective (Taylor-Silva and Riesselman, 2018). When further identification was needed, the objective was changed to 100x. Images of specimens were taken using a 63x and a 100x objective, and the scale was adjusted to match when images were placed in the same figure. Fields of view (FOV) were tallied, and counts were converted to absolute abundance (AA), reported in valves per gram of dry sediment, using the equation of Warnock and Scherer (2014):

Light microscope observations are supported by scanning electron microscope (SEM) images produced on a ZEISS Sigma FEG-SEM at the University of Otago Centre for Electron Microscopy. To prepare SEM slides, 2 mL of hydrogen peroxide and a drop of sodium hexametaphosphate were mixed with approximately 50 mg of sediment in a centrifuge tube and left overnight in a 40 °C oven. Sediment was rinsed with Elix pure water and dried before diatoms were separated from the terrigenous fraction by heavy-liquid separation. Material was centrifuged with sodium polytungstate mixed to a density of 2.15 g cm−3 to prevent clay particulates from covering the finer details of the diatom frustules. The sample was rinsed and stored in 50 mg Elix pure water. Several drops of the slurry were dried on a glass slide before the slide was gold-coated for SEM observation.

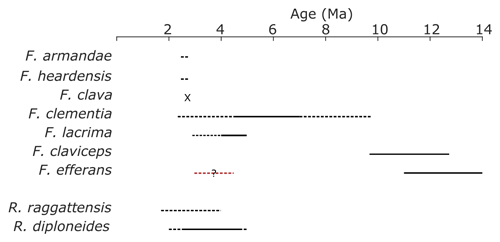

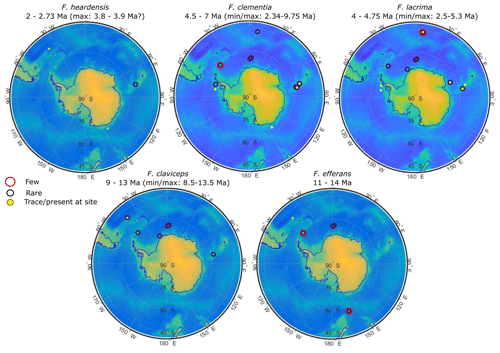

Figure 3Species age ranges. The age ranges of clavate Fragilariopsis species, R. raggattensis, and R. diploneides were approximated using Site U1361 data, published abundance records from sites noted in Table A1, and Cody et al. (2008). The black lines denote the estimated age range in which more than three sites record a presence of a species. To test the robustness of this estimate, it was compared to the average range model from Cody et al (2008), a probabilistic determination that calculated an average position of biostratigraphic events, for F. clementia, F. lacrima, F. claviceps, and R. diploneides. The dashed line indicates when a species is present at one to three sites. The question mark over the dashed red line shows when rare F. efferans specimens are identified in the Pliocene (Harwood and Maruyama, 1992; Censarek and Gersonde, 2003). The “x” denotes Marine Isotope Stage G7, the single interglacial period in which F. clava was identified at Site U1361.

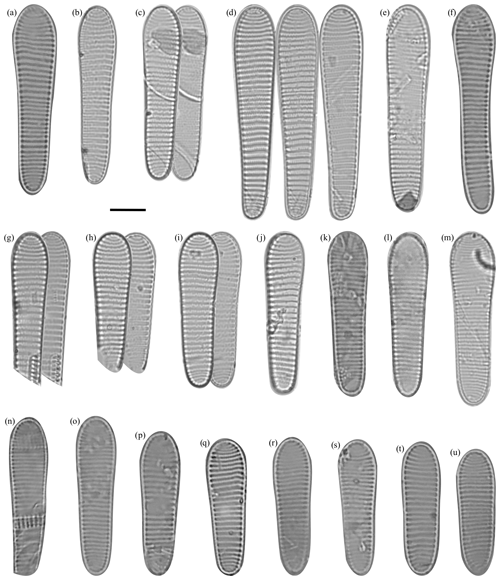

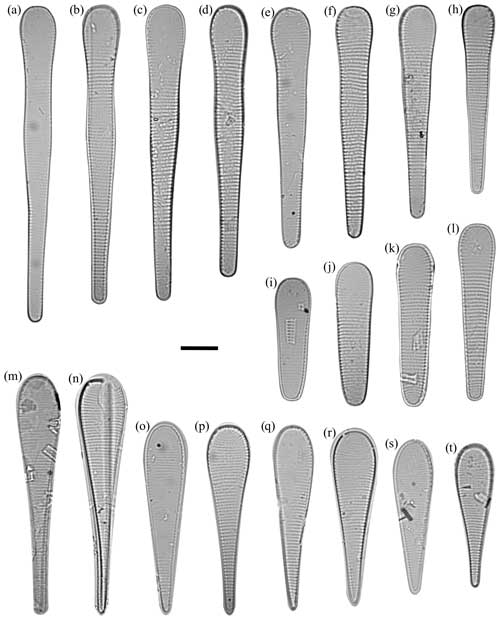

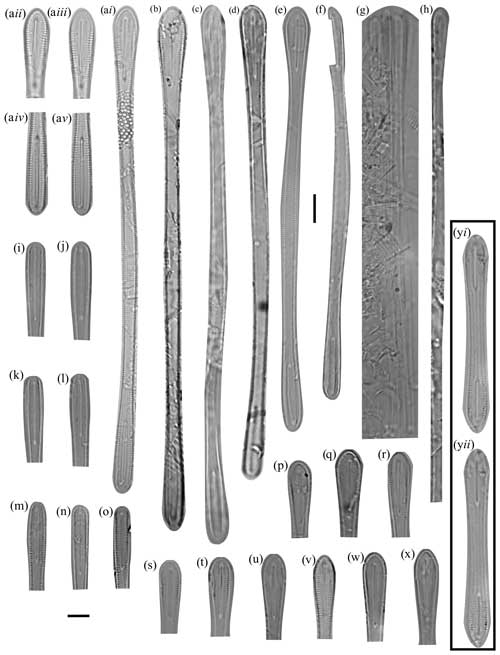

Figure 4Fragilariopsis clava light micrographs. The scale bar for all images is 10 µm. The IODP sample identifier is given for each Fragilariopsis clava sp. nov. Duke. (a) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (b) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (c) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (d) Paratype: U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. Asymmetry along apical axis as minor apex deflects from apical axis. e) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (f) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (g) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (h) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (i) Holotype: U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (j) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (k) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (l) U1361A-6H7 42–44 cm. (m) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. Costae may appear finer but are still within defined F. clava range. (n) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (o) U1361A-6H7 42–44 cm. (p) U1361A-6H7 12–14 cm. (q) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (r) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (s) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (t) Paratype: U1361A-6H7 12–14 cm. Constricted center, but apices are more proportionally equal in comparison to holotype. (u) U1361A-6H7 42–44 cm.

2.4 Diatom morphometric measurements

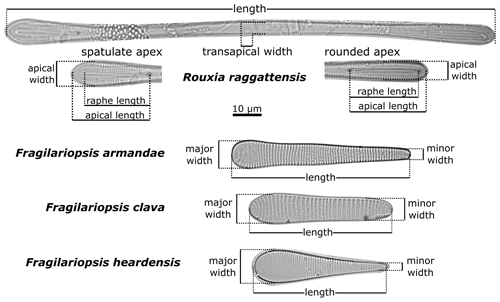

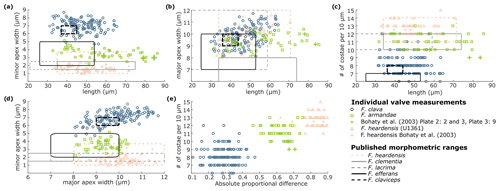

Fragilariopsis clava, Fragilariopsis armandae, and Rouxia raggattensis morphometric measurements, defined in Fig. 2, were systematically measured using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012) in order to quantitatively compare the new taxa to pre-existing species in Tables 1 and 2. The degree of symmetry between apices is a crucial defining characteristic that separates F. clava from related taxa. We have established a metric that captures the absolute proportional difference of apices to define this characteristic, with values ranging between 0–1:

An absolute proportional difference of 0 equates to symmetrical apical widths, whereas values approaching 1 indicate a high degree of asymmetry. For clavate Fragilariopsis species, we defined the narrower and wider apices as the minor and major apices, respectively.

Three new fossil diatom species are described from Pliocene and Pleistocene material collected at IODP Site U1361. New taxa are differentiated from one another and from established species based on morphometric measurements.

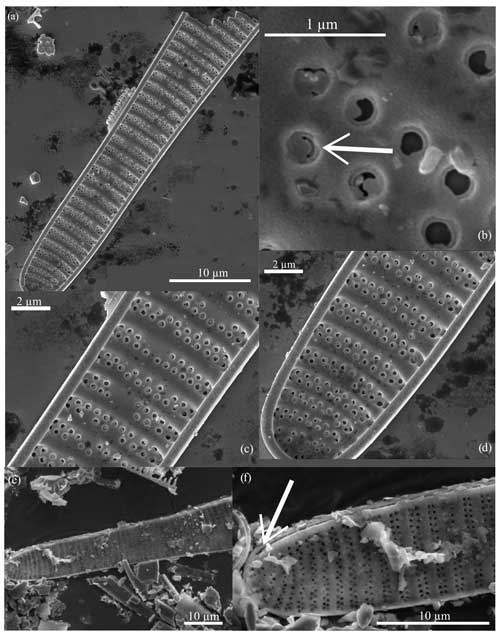

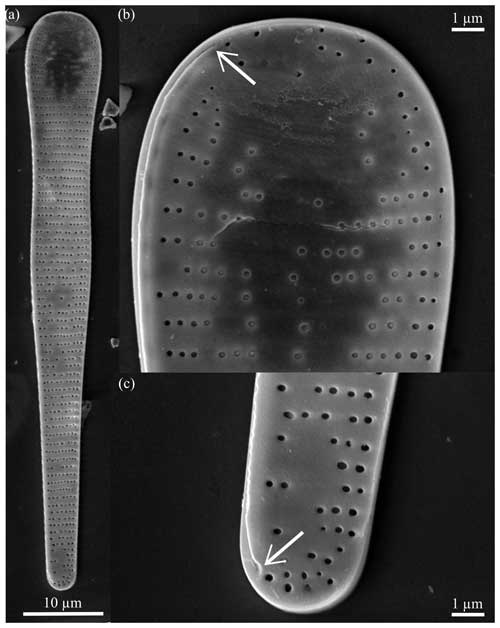

Figure 5Fragilariopsis clava scanning electron micrographs. All specimens from U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (a) Interior valve face with (c–d) close-up views of the constricted center and minor apex and (b) detail of the flap-like occlusions (arrow). Panels (a), (c), and (d) display the discontinuous areolae within striae. Panel (e) shows the exterior view of the minor apex, and panel (f) highlights the raphe (arrow) terminating along the valve edge.

3.1 Fragilariopsis clava Duke sp. nov.

Diagnosis. The valve is clavate, heteropolar, and slightly panduriform. Apices are broadly rounded, and the wide and bulbous major apex tapers to a slightly constricted center and an oblong minor apex. Transapical striae are regularly spaced, curving and branching at the apices, with biseriate transitioning to uniseriate towards the major apex and poroids parallel or alternating (Figs. 5b and c; 6a, c, and e). Striation is occasionally disrupted by patch hyaline fields. The raphe is straight and threadlike along the edge of the exterior valve face and terminates at apices with slightly deflected ends (Figs. 5f; 6d and f). Based on SEM images of well-preserved specimens, areolae are occluded by an unperforated silica membrane and are attached to the pore wall except for a curved slit opening (Figs. 5b; 6b). These flap-like occlusions are referred to as foriculae by Cox (2004, Figs. 19 and 24) and as volate occlusions by Mann (1980, Fig. 31).

Dimensions. The length is 31–66 µm (mean: 48.5 µm), the major apex width is 8–12 µm (mean: 10 µm), and the minor apex width is. 4.7–10.5 µm (mean: 7.6 µm) (Table 1). There are 6–12 costae per 10 µm (mean density: 7–9) (Fig. 4; Table 1).

Holotype. This can be seen in Fig. 4i, U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. The type level and age for the specimen is late Pliocene at 55.49 m b.s.f. (CSF-B) in Hole U1361A. Accession # 47688 is curated by the Geology Department, University of Otago, NZ.

Paratype. This can be seen in Fig. 4t, U1361A-6H7 12–14 cm, and d, U136A-6H7 32–34 cm. Accession # 47689 for specimen (t) and # 47690 for specimen (d) are curated by the Geology Department, University of Otago, NZ.

Figure 6Fragilariopsis clava scanning electron micrographs. All specimens from U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. The exterior valve face is displayed in panels (a), (c), and (e). The raphe (arrows) runs along the outer edge of the valve face, ending at the major apex as seen in panels (d) and (f), which are close-ups of panels (c) and (e), respectively. Panel (b) highlights preserved perforated membranes (arrows) from the specimen shown in panel (a).

Locality. The specimens are located at the Wilkes Land continental rise, East Antarctica.

Stratigraphic occurrence. The first and last appearances of Fragilariopsis clava overlap with the Thalassiosira vulnifica–Thalassiosira insignia diatom zone, which Harwood and Maruyama (1992) defined as ranging from the first appearance of T. vulnifica around 3.1 Ma and to the last appearance of T. insignia around 2.5 Ma.

Age. F. clava was only observed in samples from a narrow depth range, 55.59–55.30 m b.s.f. at Site U1361, correlating to a single interglacial interval, MIS G7 (2.76–2.75 Ma), based on the age model of Patterson et al. (2014).

Derivation of name. Fragilariopsis clava is named using the Latin word for club or staff, “clava”, in reference to its club-like shape.

Figure 7F. clava morphometrics. Fragilariopsis clava (blue circles) and F. armandae (green squares) morphometric measurements are compared to other clavate species in panels (a–d): F. heardensis (pink line and markers), F. clementia (solid green line), F. lacrima (dashed green line), F. efferans (solid black line), and F. claviceps (dashed black line). (a) The minor apex width is compared to the total specimen length, (b) the major apex width is compared to the total specimen length, (c) the minor apex width is compared to the major apex width, and (d) the number of costae per 10 µm is compared to the total specimen length. Panel (e) displays the number of costae per 10 µm to the absolute proportional difference of F. clava, F. armandae, and F. heardensis. Examples of F. heardensis are shown from U1361 (pink triangles) and Bohaty et al. (2003, pink crosses) (pink crosses). We suggest that specimens identified as F. heardensis in Bohaty et al. (2003) Plate 2 (Figs. 2 and 3) and Plate 3 (Fig. 9) (green crosses) should be reclassified as F. armandae or F. c.f. armandae. Fragilariopsis clava is distinguished from other Pliocene species in panels (a), (c), and (e) by its broader minor apex and coarse costae.

Remarks. Fragilariopsis is a large genus defined by a flat, usually linear valve face with rounded valve poles; parallel striae with radiation at apices; and a simple raphe positioned between the valve face and the proximal mantle (Round et al., 1990). Fragilariopsis clava has morphological affinities to an established lineage (Bohaty et al., 2003) comprising the clavate Fragilariopsis species F. heardensis Bohaty 2003 (Bohaty et al., 2003), F. clementia Gombos 1976 (Gombos, 1976), F. lacrima Gersonde 1991 (Gersonde, 1991), F. claviceps Schrader 1976 (Schrader, 1976), and F. efferans Schrader 1976 (Schrader, 1976). The F. clava holotype exhibits a broad valve outline and apices and a constricted center (Fig. 4i). The smaller paratype exhibits the same broad valve outline, coarse costae, and constricted center as the holotype, but the absolute proportional difference between apices is smaller, so valve heteropolarity is less pronounced (Fig. 4t). The elongate paratype has a deflected minor apex (Fig. 4d).

Fragilariopsis clava shares a similar heteropolar outline to F. heardensis and F. clementia, with one inflated major apex and a narrower minor apex. However, F. clava is more robust than F. heardensis, with coarser costae and a broader shape, and F. clava has more bluntly rounded apices than F. clementia (Fig. 15). Fragilariopsis clava has a smaller proportional difference (0.13–0.43, n=100) than F. heardensis (0.56–0.87, n=15) and F. clementia (∼0.7) (Table 1).

Figure 7 compares the morphologies of F. clava and related species. When Bohaty et al. (2003) first identified F. heardensis in sediments from the Kerguelen Plateau, the authors compared it to other taxa with clavate outlines: Pliocene species F. clementia and F. lacrima and Miocene species F. efferans and F. claviceps. The morphometric differences are most apparent when comparing the proportions of their outlines. All species are heteropolar, but F. clementia, F. lacrima, and F. efferans have a large proportional difference like F. heardensis. Fragilariopsis claviceps clusters with F. clava, demonstrating their shared coarse costae and low proportional difference (Fig. 7a and c).

Rare F. clava specimens have 11–12 costae per 10 µm (Fig. 15g). Fragilariopsis c.f. clementia at Site U1361 may be a transitional form between F. clementia and F. clava, with angular apices, coarse costae, and a broad outline resulting in a smaller proportional difference (Fig. 15e and f; see Sect. 4.1 for further discussion).

Figure 8Fragilariopsis armandae and F. heardensis light micrographs. The scale bar for all images is 10 µm. The IODP sample identifier is given for each of the following specimens. (a–b) F. armandae, U1361A-6H1 12–14 cm. (c) F. armandae, U1361A-6H1 142–144 cm. (d–e) F. armandae, U1361A-6H1 12–14 cm. (f) Holotype: F. armandae, U1361A-6H1 12–14 cm. (g) F. armandae, U1361A-6H2 42–44 cm. (h) F. armandae, U1361A-6H2 112–114 cm. (i) F. armandae, U1361A-6H2 92–94 cm. (j) F. armandae, U1361A-6H2 62–64 cm. (k) Paratype: F. armandae, U1361A-6H2 2–4 cm. (l) F. armandae, U1361A-6H2 52–54 cm. (m) F. heardensis, U1361A-6H2 42–44 cm. (n) F. heardensis, U1361A-6H2 92–94 cm. (o) F. heardensis, U1361A-6H1 12–14 cm. (p) F. heardensis, U1361A-6H2 82–84 cm. (q) F. heardensis, U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (r) F. heardensis, U1361A-6H1 12–14 cm. (s) F. heardensis, U1361A-6H1 142–144 cm. (t) F. heardensis, U1361A-6H2 92–94 cm.

3.2 Fragilariopsis armandae Frazer, Duke et Riesselman sp. nov.

Diagnosis. The valve is clavate and heteropolar. Apices are blunt and rounded, and the domed major apex constricts to a medial bulge and narrower minor apex. There are two endmembers: biundulate, longer valves with a slight medial bulge, narrow minor apex, and rounder apices (e.g., Fig. 8a–d) and shorter valves with a constricted center and blunter apices (e.g., Fig. 8i–l). Medial striae are transapical, curved, and branched towards the apices and are uniseriate, at times discontinuous (Table 1; e.g., Fig. 8d). The raphe is straight and threadlike along the edge of the exterior valve face (Fig. 9b and c). The raphe ends simply at the major apex and deflects towards the valve face at the minor apex.

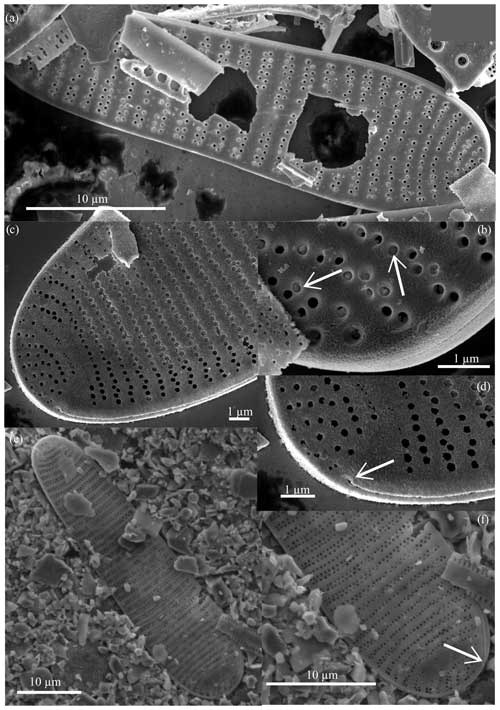

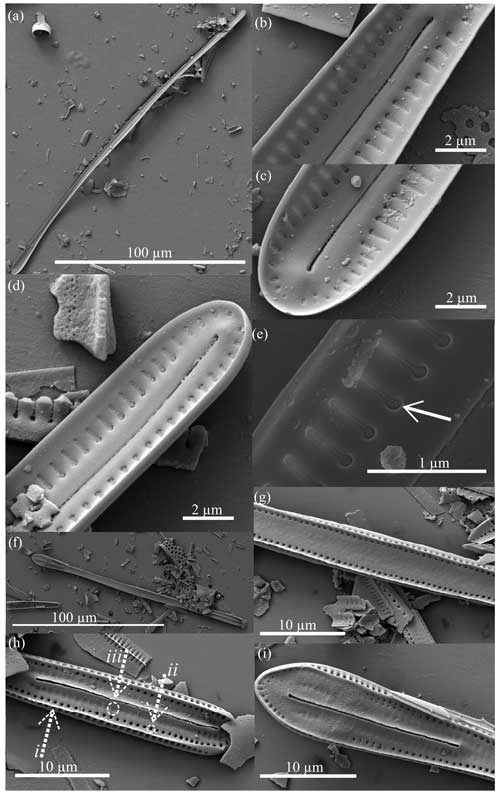

Figure 9Fragilariopsis armandae scanning electron micrographs. All specimens from U1361A-6H1 12–14 cm. (a) Exterior valve face with irregular, uniseriate areolae. The raphe runs along the outer edge of the valve face, ending at the major apex as seen in panel (b) and the minor apex in panel (c), which are close-ups of panel (a).

Dimensions. The length is 32.85–86.40 µm (mean: 57.27 µm), the major apex width is 8.09–10.70 µm (mean: 9.40 µm), and the minor apex width is 2.23–5.16 µm (mean: 3.59 µm) There are 10–13 costae per 10 µm (Table 1).

Holotype. This can be seen in Fig. 8f, U1361A-6H1, 12–14 cm. The type level and age for the specimen is late Pliocene at 47.13 m b.s.f. (CSF-B) in Hole U1361A. Accession # 47691 is curated by the Geology Department, University of Otago, NZ.

Paratype. This can be seen in Fig. 8k, U1361A-6H2 2–4 cm. Accession # 47692 is curated by the Geology Department, University of Otago, NZ.

Locality. The specimens are located at the Wilkes Land continental rise, East Antarctica.

Stratigraphic occurrence. The range of F. armandae bridges the Thalassiosira vulnifica–T. insignia and T. vulnifica diatom zones. Harwood and Maruyama (1992) defined the lower boundary of the T. vulnifica diatom zone as the last appearance of T. insignia around 2.5 Ma and the upper boundary as the last appearance of T. vulnifica around 2.2 Ma.

Age. F. armandae is observed in samples from depths of 49.57–47.13 m b.s.f. which correspond approximately to MIS 101 and 97 (∼2.58–2.47 Ma).

Derivation of name. Fragilariopsis armandae is named in honor of the late Dr. Leanne Armand in recognition of her seminal contributions to the field of Southern Ocean diatom micropaleontology and her deep and selfless commitment to the advancement of our community.

Figure 10Rouxia raggattensis light micrographs. The 10 µm scale bar in the upper half of the figure applies to whole R. raggattensis specimens (a–h) and the Rouxia diploneides in (y), and the 10 µm scale bar in the bottom left applies to R. raggattensis apices (i–x). (a) Holotype: U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. Panels (aii–v) show the apices at different focuses. (b) U1361A-5H2 132–134 cm. (c, d) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (e) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (f) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. (g) U1361A-6H7 42–44 cm, preserved chain of Rouxia raggattensis. h) U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm exemplifies the long length of Rouxia raggattensis, which is rarely preserved intact. (i) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (j) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (k) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (l) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (m) U1361A-6H4 120–122 cm. (n) U1361A-6H2 82–84 cm. (o) U1361A-6H2 82–84 cm. (p) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (q) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (r) U1361A-6H4 120–122 cm. (s) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (t) U1361A-6H4 120–122 cm. (u) U1361A-6H4 120–122 cm. (v) U1361A-6H4 120–122 cm. (w) U1361A-6H1 132–134 cm. (x) U1361A-6H4 21–23 cm. (y) U1361A-4H6 2–4 cm, Rouxia diploneides. Apices are isopolar, and the center is only slightly narrower than apices.

Remarks. The holotype of F. armandae exhibits discontinuous poroids and a blunt major apex that constricts to a slight medial bulge and a narrow minor apex. The paratype has a lower absolute proportional difference than the holotype and a valve face with nearly straight sides as they taper to the minor apex. The minor apex width, absolute proportional difference, and medial bulge distinguish F. armandae from the most similar clavate Fragilariopsis species, F. clava and F. heardensis. Fragilariopsis armandae clusters between F. clava and F. heardensis when their absolute proportional difference and minor apex width is compared (Fig. 7e). Fragilariopsis armandae has a robust clavate valve shape similar to F. clava but, unlike F. clava, it is uniseriate, and it has discontinuous poroids and finer costae. The blunter, almost flat apices of F. armandae further separate the shorter endmember of this species (e.g., Fig. 8i and j) from short specimens of F. clava (e.g., Fig. 4q), which are similarly proportioned. The longer endmember of F. armandae is distinguishable from long specimens of F. clava by its medial bulge and the arrangement of its poroids.

Fragilariopsis armandae is differentiated from F. heardensis by its lower absolute proportional difference, slightly coarser striation, and discontinuous poroids. The major apex of the F. heardensis holotype from Bohaty et al. (2003, shown in Fig. 15) is blunt like the wide apex of F. armandae, but the sides of the valve face do not constrict when narrowing to the smaller apex. Three specimens identified as F. heardensis by Bohaty et al. (2003) and displayed in their Plate 2 (Figs. 2 and 3) and Plate 3 (Fig. 9) have valve shapes, coarser costae, wider minor apices, and longer lengths more similar to F. armandae than F. heardensis (Table 1 and Fig. 7). See Sect. 4.1 for further discussion.

Figure 11Rouxia raggattensis scanning electron micrographs. All specimens from U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. Panels (b–e) are close-ups of the interior valve face shown in panel (a), and panels (g–i) are close-ups of the exterior valve face in panel (f). Panels (b–c), (e), and (i) are the spatulate apex, and panels (d) and (f) show the rounded apex. Panels (b–d) show the keyhole-shaped alveolar openings which decrease in size towards the apices where the raphe terminates. Panel (e) displays the perforated membrane of the alveolate striae (arrow). Panel (h) highlights the marginal ridge (dashed arrow i), rows of pores (dashed arrow ii), and ovular impressions (dashed arrow iii).

3.3 Rouxia raggattensis Duke et Riesselman sp. nov.

Synonymy. Synonyms are Rouxia sp. A in Harwood and Maruyama (1992), Plate 17 Fig. 11, and Rouxia sp. A of Harwood and Maruyama in Riesselman and Dunbar (2013), Fig. 5.

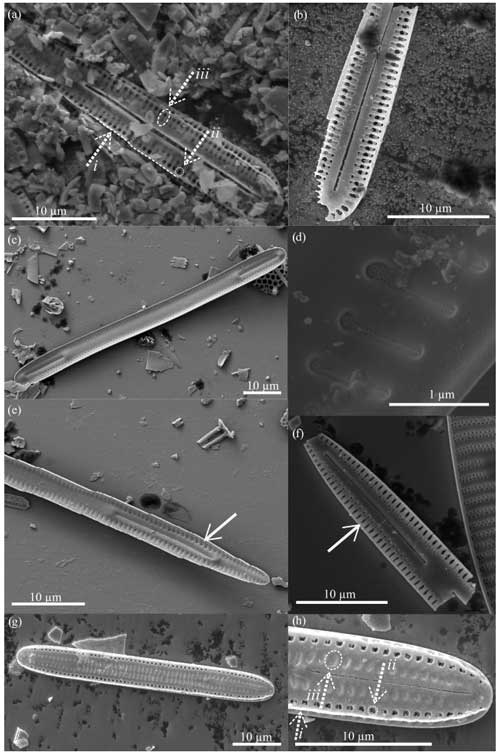

Figure 12Rouxia raggattensis, R. antarctica, R. isopolica, and R. leventerae scanning electron micrographs. All specimens from U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. Dissolution of R. raggattensis (a) exterior and (b) interior valve face reveals the frustule structure between surfaces. Panel (a) highlights the marginal ridge (dashed arrow i), rows of pores (dashed arrow ii), and ovular impressions (dashed arrow iii). (c) Rouxia antarctica interior view and (d) example of keyhole-shaped alveoli from R. antarctica. White arrows in panels (e) and (f) point to keyhole-shaped alveoli in R. isopolica and R. leventerae, respectively. Panel (g) exhibits the exterior view of R. antarctica, and panel (h) is a close-up of an apex which displays features similar to R. raggattensis.

Diagnosis. The valve is long and bilobate (Fig. 10a–f). One apex is cuneate and spatulate (Fig. 10p–x), and the other is narrow and rounded (Fig. 10i–o). Apices are connected by a long, semi-convex central hyaline bar, perforated by rows of marginal pores (Fig. 10a–f). The raphe is simple and threadlike with simple ends (Figs. 10; 11b–d and h–i).

Information about the striae, alveoli, and silica structure was determined by SEM imaging (Fig. 11). Striae are alveolate, consisting of a single elongate chamber with a wider semicircular medial end (keyhole-shaped; Fig. 11b–e). The elongated section is perforated by two rows of fine pores on the Site U1361 specimen (Fig. 11e) and by three to four rows on specimens from AND-1B (Riesselman and Dunbar, 2013, Fig. 5 panels 7 and 8). The distribution of pores at the semicircular end is more disorganized and irregular (Fig. 11e). Alveoli towards the tip of the apex are smaller and have no circular end (Fig. 11c and d), and, in the central bar, alveoli are oblong. The exterior marginal ridge is narrower than the interior valve face (Fig. 11g–i). The pores on the edge of the exterior valve face align with the center of the alveoli on the interior valve face (Figs. 11g–i; 12a and b). Faint circular impressions run parallel to the pores on the external valve face and align with the medial ends of the interior alveoli (Figs. 11g–h; 12b).

Figure 13R. raggattensis and R. diploneides morphometrics. R. raggattensis morphometrics (blue circles) are compared to those of R. diploneides (red squares) (see Fig. 2). (a) The apex length is compared to the length of the raphe on the apex, (b) the length of one apex is compared to the length of the other, (c) the apex length is compared to its width, and (d) the total specimen length is compared to the transapical width. Rouxia raggattensis spatulate apices are shown as open circles, whereas the rounded apices are solid circles. The apices on a single specimen have a nearly symmetrical length for both R. raggattensis and R. diploneides, but the R. raggattensis spatulate apex is wider than its rounded apex, and, in general, R. diploneides is smaller and has shorter apices than R. raggattensis.

Dimensions. The length is 120–201 µm (mean 161.5 µm), the medial width is 3.1–5.2 µm (mean 4.15 µm), the spatulate apex length is 17.5–26.1 µm, the spatulate raphe length is 14.4–22.3 µm, the spatulate apex width is 5.1–8.2 µm, the rounded apex length is 17.8–25.8 µm, the rounded raphe length is 15.3–23.0 µm, and the rounded apex width is 3.4–7.1 µm. There are 12–15 costae per 10 µm (Table 2).

Holotype. This can be seen in Fig. 10a, U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm. The age and type level for the holotype specimen is late Pliocene at 55.49 m b.s.f. (CSF-B) in Hole U1361A. Accession # 47693 is curated by the Geology Department, University of Otago, NZ.

Locality. The specimens are located at the Wilkes Land continental rise, East Antarctica.

Figure 14Example F. clementia specimens from around the Southern Ocean. The figure exemplifies the morphological range in Fragilariopsis clementia observed around the Southern Ocean based on published (source provided above specimens) and unpublished specimen examples. From left to right, specimens from Hole U1543A are from samples (a) U1543A-23H4 120 cm, (b) U1543A-23H4 120 cm, (c) U1543A-23H5 120 cm, (d) U1543A-23H6 120 cm, and (e) U1543A-23HCC 18–24 cm. Specimens from Hole U1541C are from two samples: panels (f–i) are from U1541C-11H3 20–21 cm, and panels (j–k) are from U1541C-11H5 20–21 cm. F. c.f. clementia specimens from Hole U1361A are from sample U1361A-8H3 72–74 cm. Specimens from Site ODP 1092 are reprinted from the Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Vol. 45, Censarek and Gersonde. Miocene diatom biostratigraphy at ODP sites 689, 690, 1088, and 1092 (Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean), pages 309–356, © 2023, are reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Age. Shipboard biostratigraphy from IODP Exp. 318 Site U1361 Hole A identified R. raggattensis apices (as Rouxia sp. spatulate, long heteropolar) in sample 10HCC 19–24 cm (94.94–94.99 m b.s.f. CSF-B; Escutia et al., 2011), placing the species in sediment as old as 4.06 Ma (Patterson et al., 2014; Tauxe et al., 2015). The last occurrence of R. raggattensis at Site U1361 was identified in sample 5H1 2–4 cm (37.53 m b.s.f. CSF-B), which corresponds to ∼2.06 Ma. Rouxia raggattensis has previously been documented as Rouxia sp. A Harwood and Maruyama in the late Pliocene (3.6–3.0 Ma) sediments from ANDRILL Site AND-1B (see Sect. 4.2 for more detail).

Derivation of name. Rouxia raggattensis is named for the Raggatt Basin on the Kerguelen Plateau, where David Harwood and Toshiaki Maruyama first documented this species from late Pliocene sediments collected during ODP Leg 120 from Site 751A (Harwood and Maruyama, 1992, Plate 17 Fig. ll).

Remarks. Complete specimens of R. raggattensis are rarely preserved because the long narrow central bar is fragile; however, apical fragments are common. The holotype displays distinct and clear examples of the spatulate and rounded apices attached by a narrow semi-convex central bar. Rouxia diploneides Schrader (1973) has a similar valve outline to R. raggattensis, where the two apices taper below the end of the raphe to a narrower central bar. However, R. diploneides is isopolar, the valve center is only slightly narrower than the apices, and the total length is shorter than R. raggattensis (Fig. 10y; Table 2). Fragmented R. raggattensis apices are distinguishable from R. diploneides because the apices have a narrower taper to the central area than R. diploneides. The alveoli and interior structure of Rouxia raggattensis are comparable to other Rouxia species. The keyhole-shaped alveoli are notable on apices of Rouxia antarctica, Rouxia isopolica, and Rouxia leventerae (Fig. 12c–f). Interior views of Rouxia antarctica also have similar features to R. raggattensis (Fig. 11g and h).

4.1 Clavate Fragilariopsis evolution, regional occurrences, and environmental affinities

Clavate Fragilariopsis species diversified in the late Pliocene in the Southern Ocean. Fragilariopsis clava appears to have evolved from F. clementia based on transitional forms at Site U1361. The evolutionary relationships between F. clava, F. armandae, and F. heardensis are more difficult to discern.

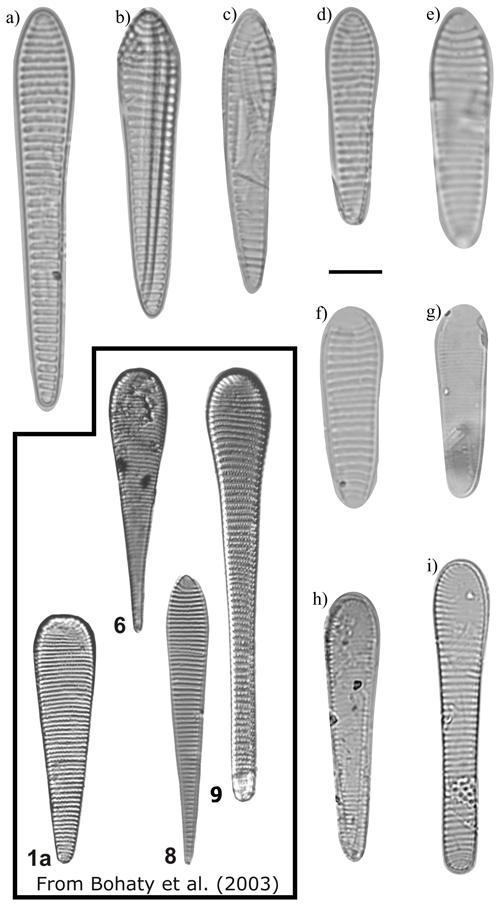

Figure 15Fragilariopsis c.f. clementia, F. clementia–F. clava transitional form, and F. clava light micrographs. The scale bar for all images is 10 µm. The black box encloses specimens from ODP Site 1138 reproduced from Bohaty et al. (2003) Plate 2 (Fig. 1a: F. heardensis (holotype); Fig. 6: F. heardensis; and Fig. 8: F. clementia) and Plate 3 (Fig. 9: F. heardensis). (a) F. c.f. clementia, U1361A-8H3 72–74 cm. (b) F. c.f. clementia, U1361A-8H3 72–74 cm. (c) F. c.f. clementia, U1361A-8H3 72–74 cm. (d) F. c.f. clementia, U1361A-7H2 22–24 cm. (e) F. clementia–F. clava transitional form, U1361A-7H2 22–24 cm. (f) F. clementia–F. clava transitional form, U1361A-7H1 92–94 cm. (g) F. clava U1361A-6H7 42–44 cm. (h) F. c.f. heardensis, U1361A-6H5 12–14 cm. (i) F. clava, U1361A-6H7 32–34 cm, to which the Bohaty et al. (2003) specimen (9) has a similar valve outline.

Fragilariopsis clementia is most commonly observed in Southern Ocean sediments dated between 7–4 Ma (total age range: 10–3 Ma; see Fig. 14). The taxon has a wide geographical distribution and two morphological endmembers (Fig. 14). The major apex of the elongate endmember has parallel sides, whereas shorter species may be convex (Gombos, 1976). Both endmembers are present in Fig. 14, which presents F. clementia specimens by site and gives an estimated age based on published age models (Gombos, 1976; Gersonde and Burckle, 1990; Censarek and Gersonde, 2002; Bohaty et al., 2003; Iwai and Winter, 2002; Harwood and Maruyama, 1992). Specimens selected to be included in a publication serve as a representation of what authors identified as F. clementia at a given location. Fragilariopsis clementia in the vicinity of the Drake Passage and the Weddell Sea appears to present most frequently in an elongate form with rounded apices (e.g., Iwai and Winter, 2002; Gombos, 1976; Gersonde and Burckle, 1990). In comparison, F. clementia from the Indo-Pacific presents with a convex valve face and a wider, more angular, and cuneate board apex (e.g., Bohaty et al., 2003). It is possible that the observed regional differences are due to author bias, change in F. clementia species concepts over time, or an evolution of the taxon. However, the sites exhibiting more elongate F. clementia are sourced from papers authored by different scientists and published in different decades. While out of the scope of this paper, a deeper investigation into F. clementia morphologies may be fruitful if original site material was revisited to make observations using a light microscope and SEM.

Figure 16Relative abundance of clavate species by ODP and IODP site. Site numbers and specifications are given in Appendix Tables A1 and A2. Symbols at each site represent the relative abundance given by the literature: large red circles denote a few occurrences, black circles indicate rare abundances, and solid yellow circles show where there were trace or scarce occurrences or single-specimen observations.

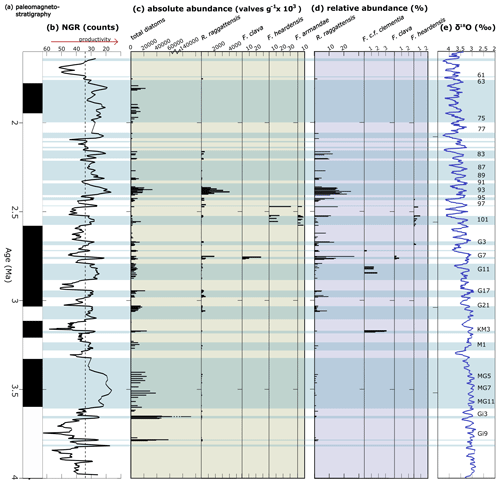

Although F. clementia was previously identified at Site U1361 between 70.04–57.19 m.b.s.f. (3.17–2.8 Ma) (Taylor-Silva and Riesselman, 2018), this occurrence is much younger than the established taxon ranges for both morphological endmembers (Cody et al., 2008; Crampton et al., 2016). Constrained optimization has been used to model the last appearance of F. clementia, with the average range model placing the datum between 4.6–4.0 Ma and the total range model placing it around 2.37–2.34 Ma (Cody et al., 2008; Crampton et al., 2016). In the course of our work documenting new clavate Fragilariopsis taxa from Site U1361, we have re-examined the original sides and determined that these younger specimens should be reclassified as F. c.f. clementia. Specimens have angular apices and valve outlines that resemble the F. clementia specimens identified by Bohaty et al. (2003) in mid-Pliocene sediments collected from the Kerguelen Plateau in the Indian Ocean, but they also have a broad minor apex and coarse striae similar to the morphology of F. clava sp. nov. The first occurrence of F. c.f. clementia at Site U1361 at 70.04 m b.s.f. (∼3.17 Ma) corresponds to the mid-Pliocene warm interval at MIS KM3 (Fig. 17). Fragilariopsis c.f. clementia is next observed at Site U1361 during a prolonged period of productivity from 2.84–2.8 Ma (58.14–57.19 m b.s.f.). The last occurrence occurs at 54.24 m b.s.f. (∼2.72 Ma) as one specimen.

Figure 17Abundance of R. raggattensis, F. clava, and other clavate Fragilariopsis species. Absolute and relative abundance of R. raggattensis, F. clava, F. armandae, and other relevant species. (a) The paleomagnetic reversal stratigraphy at Site U1361 (Escutia et al., 2011). (b) Site U1361 shipboard natural gamma radiation (NGR; counts) (Escutia et al., 2011). (c) Absolute abundance of total diatoms counted at Site U1361 and species of interest. (d) Relative abundance of species of interest that were identified during diatom counts. (e) Benthic oxygen isotope (δ18O) stack of Lisiecki and Raymo (2005). Low NGR denotes lower clay content which is potentially linked to higher biological deposition. The light-blue shaded areas highlight intervals in which NGR is lower than 34, the threshold used by Tauxe et al. (2015) to indicate times of higher productivity. More positive δ18O values indicate cooler conditions. Marine Isotope Stages corresponding to low NGR are given to the far right. The absolute and relative abundance between 84.94–56.53 m b.s.f. were completed by Taylor-Silva and Riesselman (2018).

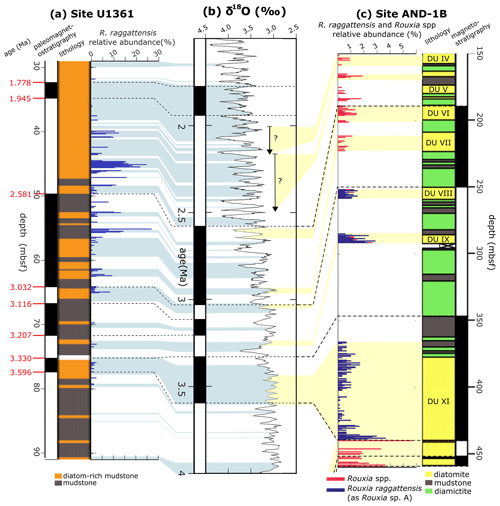

Figure 18Rouxia raggattensis relative abundance at Site U3161 and AND-1B. AND-1B lithology sourced from McKay et al. (2012). (a) Site U1361 paleomagnetic reversal stratigraphy (Escutia et al., 2011), graphical lithology, and R. raggattensis relative abundance (blue bars). (b) Benthic oxygen isotope stack of Lisiecki and Raymo (2005). (c) Site AND-1B magnetostratigraphy, graphical lithology, and R. raggattensis and Rouxia spp. (pink bars) relative abundance (McKay et al., 2012; Riesselman and Dunbar, 2013; Sjunneskog and Winter, 2012). AND-1B diatom units (DU) are labeled in the lithology. The relative abundance measurements between 84.94–56.53 m b.s.f. were completed by Taylor-Silva and Riesselman (2018). The relative abundance of undifferentiated Rouxia spp. in AND-1B sediments is also shown because this may include unidentified R. raggattensis fragments.

It is more difficult to determine when F. heardensis and F. armandae evolved in relation to F. clava. Both species are present at Site U1361 between MIS 101–97 (∼2.6–2.47 Ma), while characteristically robust F. clava specimens are present at Site U1361 during MIS G7 at ∼2.73 Ma (Fig. 17) alongside endmembers with finer costae. The paper that formally describes F. heardensis, Bohaty et al. 2003, is the only literature that explicitly lists F. heardensis in its diatom assemblage at ODP Site 1138 on the Kerguelen Plateau in the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean. Bohaty et al. (2003) originally identified two morphotypes for F. heardensis: the holotype (Plate 2 Fig. 1a and b; shown in Fig. 15) and the specimens that more closely resemble F. armandae (Plate 2 Figs. 2–3 and Plate 3 Fig. 9; example in Fig. 15). The latter morphotype shares a constricted center and possible medial bulge with F. armandae. However, one specimen (Bohaty et al., 2003 Plate 3 Fig. 9) is biseriate in the center, and all specimens have 9–10 costae, characteristics more comparable to F. clava than F. armandae. We suggest these specimens could be reclassified as F. armandae or F. c.f. armandae. All three specimens are from the same sample (138-1138A-8R-CC) dated about 3 Ma, approximately 0.2–0.3 Ma older than the holotype F. heardensis presented by Bohaty (138-113A-8R-5, 100–101 cm). The age difference between the appearance of F. clava and F. heardensis at Site U1361 is also about 0.2–0.3 Ma.

The Fragilariopsis heardensis Bohaty et al. (2003) holotype is a similar age to trace occurrences of F. efferans or F. c.f. efferans recorded in the late Pliocene by older literature records, although the diatom taxon is typically observed in middle Miocene sediments (∼14.5–11 Ma; Ciesielski, 1983; Gersonde and Burckle, 1990; Schrader, 1976). Because F. efferans has not been found in Late Miocene (10–6 Ma) sediments (Censarek and Gersonde, 2003; Ciesielski, 1983; Gersonde and Burckle, 1990; Harwood and Maruyama, 1992; Schrader, 1976), we suggest that traces of F. efferans in the Pliocene are either reworked Middle Miocene specimens or misidentified Pliocene clavate species. Gombos (1976) identified a specimen as F. c.f. efferans from ODP Site 328 located in the outer Malvinas Basin at ∼2.9–2.8 Ma, which has the characteristic morphology of F. heardensis. Other examples of Pliocene F. efferans come from late Pliocene sediment (3.8–2.6 Ma) collected from ODP sites 747 and 748 on the Kerguelen Plateau (Harwood and Maruyama, 1992) and from mid-Pliocene sediments (∼4.5 Ma) from ODP Site 1092 (Censarek and Gersonde, 2003). Fragilariopsis heardensis is less common than F. clementia, but its geographical distribution expands to cover a similar area to F. clementia (Fig. 16) if alternative identifications from older literature are considered.

The origination and extinction of F. clava, F. armandae, F. heardensis, and transitional forms occurred during a period of pronounced diatom species turnover between 3–2 Ma, related to changing climate conditions (Crampton et al., 2016). Although clavate Fragilariopsis species are not common in Southern Ocean sediments, they are observed in trace to rare amounts in the region affected by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) (Fig. 16). Miocene and early Pliocene taxa thrived in relatively warm open-ocean conditions impacted by the ACC. Temperatures were warmer and CO2 concentrations higher during the Miocene and early- to mid-Pliocene (Pagani et al., 2009; Seki et al., 2010; Sangiorgi et al., 2018; Zachos et al., 2008). Pliocene occurrences of F. c.f. clementia at Site U1361 have been indirectly associated with warmer subantarctic waters circulating southward, closer to the Antarctic continental margin (Taylor-Silva and Riesselman, 2018). The Wilkes Land continental rise is situated to the east and south of the Kerguelen Plateau and is a place where regional bathymetry constricts the eastward-flowing ACC to a more southerly position (Barron, 1996; Orsi et al., 1995). The onset of cooler sea surface temperatures and increased sea ice in the late Pliocene may have marginalized clavate Fragilariopsis species and facilitated their extinction and the extinction of many other diatom species (Crampton et al., 2016). We speculate that F. clava, F. armandae, and F. heardensis evolved as the clavate Fragilariopsis lineage attempted to adapt to cooling climate conditions in the Southern Ocean, ultimately unsuccessfully.

4.2 Rouxia raggattensis age constraints

Rouxia raggattensis persisted from at least the mid-Pliocene through to the Early Pleistocene. To better constrain the first appearance of R. raggattensis, we compare the occurrences from Site U1361 to occurrences from ANDRILL core AND-1B (Fig. 18). Samples from U1361 were examined down to 94.9 m b.s.f. (4.05 Ma), and possible trace fragments of R. raggattensis were identified, although poor preservation generates some uncertainty in identification. In AND-1B, R. raggattensis was consistently present in three diatom units (VIII, IX, and XI) in trace amounts (maximum relative abundance: 3.67 %) from approximately 3.6–3.0 Ma (McKay et al., 2012; Riesselman and Dunbar, 2013; Sjunneskog and Winter, 2012) (Fig. 18). Rouxia raggattensis was not identified below an unconformity at 440 m b.s.f. in diatom unit XI, which corresponds to an approximately 0.7 Ma time gap between 3.64 to 4.34 Ma (Konfirst et al., 2011; Scherer et al., 2007). The unconformity prevents observing the first occurrence of R. raggattensis in the Ross Sea and Wilkes Land area, but we propose R. raggattensis evolved sometime between 4.3–4.05 Ma based on its occurrence in sediments from U1361 and AND-1B.

The abundance of Rouxia raggattensis is not constant at Site U1361. Relative abundance is low from 4.05 until 3.15 Ma (64.94 m b.s.f.), about MIS G21, when the relative abundance exceeds 5 %. The absolute abundance also increases slightly during MIS G21 followed by a dramatic increase at 2.81 Ma (MIS G9). Rouxia raggattensis becomes a significant secondary species, reaching a maximum relative abundance of 26.9 % at 2.74 Ma (55.14 m b.s.f.) and maximum absolute abundance at 2.44 Ma (46.34 m b.s.f.); from ∼2.16 Ma (39.92 m b.s.f.), its abundance rapidly declines. The decrease in abundance of R. raggattensis suggests that environmental conditions along the Wilkes Land margin became progressively less favorable as Pleistocene cooling progressed. Rouxia raggattensis briefly reappears in the youngest U1361 sample examined in this study, 1.76 Ma (31.83 m b.s.f.), in low relative abundances (1.9 %).

4.3 Rouxia raggattensis regional and environmental occurrences

The maximum abundance of R. raggattensis coincides with a dynamic period (2.8–2.4 Ma) of instability in Antarctic and Southern Ocean conditions (Barron, 1996; Hillenbrand and Cortese, 2006; Naish et al., 2009; Crampton et al., 2016; Tauxe et al., 2015; Bertram et al., 2018) during which Northern Hemisphere glaciation intensified (Balco and Rovey, 2010; Jansen and Sjoholm, 1991; Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Naafs et al., 2013; Rea and Schrader, 1985; Shackleton et al., 1984). By summing the rate of diatom extinction and origination, Crampton et al. (2016) identified five periods of major species turnover in the last 15 Ma, including from 2–3 Ma. Diatom speciation is sensitive to sea ice extent; non-ice-adapted species are marginalized when open-water niches south of the Polar Front are lost to expanding sea ice (Crampton et al., 2016). However, as other diatom species went extinct as surface conditions cooled, R. raggattensis seems to have thrived, particularly when sea ice was present. At Site U1361, R. raggattensis is strongly correlated (r=0.78) with Fragilariopsis sublinearis, an extant species associated with locations with 7 or more months of sea ice a year (Armand et al., 2005). Relative abundances of F. sublinearis greater than 2 % are correlated to places with winter sea ice, such as the Ross Sea, Prydz Bay, Wilkes Land, and the Weddell Sea (Armand et al., 2005; Cefarelli et al., 2010). Rouxia raggattensis reached a maximum relative abundance (26.92 %) at ∼2.74 Ma (55.14 m b.s.f. in MIS G7), close to a major cooling step recorded in deep-sea temperatures at 2.73 Ma associated with the intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciation (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005; Rohling et al., 2014; Woodard et al., 2014). Furthermore, the relative abundance of R. raggattensis decreased dramatically at ∼2.16 Ma (39.92 m b.s.f.), at about the same time as a reduction in iceberg calving (Patterson et al., 2014; Rohling et al., 2014) and an inferred reduction in the extent of sea ice. We therefore surmise that R. raggattensis was a sea-ice-affiliated species that preferred surface water conditions dominated by cold temperatures.

This paper describes three new diatom taxa: Fragilariopsis clava sp. nov. Duke; Fragilariopsis armandae sp. nov. Frazer, Duke et Riesselman; and Rouxia raggattensis sp. nov. Duke et Riesselman. Fragilariopsis clava, distinguishable by a robust clavate valve face with coarse costae, existed briefly at Site U1361 during Marine Isotope Stage G7, around 2.74 Ma. Transitional forms provide evolutionary links between F. clava sp. nov. and F. clementia Gombos. Fragilariopsis armandae is present at Site U1361 during the same Marine Isotope Stages, MIS 101–97 (∼2.68–2.47 Ma), as F. heardensis. We speculate that F. armandae and F. heardensis evolved from the same branching point that separated uniseriate clavate Fragilariopsis species from biseriate species (e.g., F. clava). Although present throughout the Pliocene-Pleistocene sediments examined for this study, R. raggattensis sp. nov. was more abundant from about 3–2 Ma when the Southern Ocean underwent significant cooling. Rouxia raggattensis appears to be associated with sea ice conditions based on its strong correlation with F. sublinearis, an extant Southern Ocean species. We speculate that R. raggattensis first appeared at Site U1361 between 4.3–4.05 Ma and last occurred between 2–2.2 Ma.

The ImageJ software is free to access online at https://imagej.net/downloads, and users should cite Schneider et al. (2012).

The absolute abundance and morphometric measurements of R. raggattensis, F. clava, and F. armandae are available as an Excel file in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-43-139-2024-supplement.

GD and JF completed diatom counts and morphometric measurements for Expedition 318 samples. BTS counted Rouxia raggattensis fragments and other diatom taxa for depths 83.99–56.53 m b.s.f. CR provided ANDRILL samples and shipboard samples and data from IODP Expeditions 318 and 383. GD, JF, and CR developed species concepts and prepared formal definitions. GD wrote the paper with input from JF and CR.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Journal of Micropaleontology. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This article is part of the special issue “Advances in Antarctic chronology, paleoenvironment, and paleoclimate using microfossils: Results from recent coring campaigns”. It is not associated with a conference.

Samples were provided by the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Gulf Coast Repository. We thank the Australia and New Zealand IODP Consortium (ANZIC); the U.S. Science Support Program; and the science parties, technical support, and platform operators at IODP Expedition 318 and 383 for enabling this work. We are grateful to Marianne Negrini for assistance using the SEM. Finally, we celebrate the life and legacy of Leanne Armand (1968–2022), whose excellence in the field of diatom micropaleontology and leadership as Director of ANZIC left a lasting impression on all who had the privilege of working alongside her. Leanne Armand, you are deeply missed.

This research has been supported by the Marsden Fund (grant no. UOO-1315) and the Ministry for Business Innovation and Employment Antarctic Science Platform (grant no. ANTA1801). The authors received support from a Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund Fast-Start (grant UOO-1315) to Christina Riesselman, a University of Otago Doctoral Scholarship to Grace Duke, and University of Otago undergraduate summer research scholarships to Josie Frazer.

This paper was edited by David Harwood and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Armand, L. K., Crosta, X., Romero, O., and Pichon, J. J.: The biogeography of major diatom taxa in Southern Ocean sediments: 1. Sea ice related species, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 223, 93–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.02.015, 2005. a, b, c

Armbrecht, L. H., Lowe, V., Escutia, C., Iwai, M., McKay, R., and Armand, L. K.: Variability in diatom and silicoflagellate assemblages during mid-Pliocene glacial-interglacial cycles determined in Hole U1361A of IODP Expedition 318, Antarctic Wilkes Land Margin, Mar. Micropaleontol., 139, 28–41, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2017.10.008, 2018. a

Balco, G. and Rovey, C. W.: Absolute chronology for major Pleistocene advances of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, Geology, 38, 795–798, https://doi.org/10.1130/G30946.1, 2010. a

Barron, J. A.: Diatom constraints on the position of the Antarctic Polar Front in the middle part of the Pliocene, Mar. Micropaleontol., 27, 195–213, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(95)00060-7, 1996. a, b, c

Bertram, R. A., Wilson, D. J., van de Flierdt, T., McKay, R. M., Patterson, M. O., Jimenez-Espejo, F. J., Escutia, C., Duke, G. C., Taylor-Silva, B. I., and Riesselman, C. R.: Pliocene deglacial event timelines and the biogeochemical response offshore Wilkes Subglacial Basin, East Antarctica, Earth aPlanet. Sc. Lett., 494, 109–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2018.04.054, 2018. a, b, c

Bohaty, S. M., Wise Jr., S. W., Duncan, R. A., Moore, C. L., and Wallace, P. J.: 9. Neogene Diatom Biostratigraphy, tephra stratigraphy, and chronology of ODP Hole 1138A, Kerguelen Plateau, Proceedings of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, 183, 1–53, 2003. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j

Cefarelli, A. O., Ferrario, M. E., Almandoz, G. O., Atencio, A. G., Akselman, R., and Vernet, M.: Diversity of the diatom genus Fragilariopsis in the Argentine Sea and Antarctic waters: Morphology, distribution and abundance, Polar Biol., 33, 1463–1484, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-010-0794-z, 2010. a

Censarek, B. and Gersonde, R.: Miocene diatom biostratigraphy at ODP sites 689, 690, 1088, 1092 (Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean), Mar. Micropaleontol., 45, 309–356, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-8398(02)00034-8, 2002. a

Censarek, B. and Gersonde, R.: 10. Data report: Relative abundance and stratigraphic ranges of selected diatoms from Miocene sections at ODP Sites 689, 690, 1088, and 1092 (Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean), Procceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, 177, 1–14, 2003. a, b, c

Ciesielski, P. F.: The Neogene and Quaternary Diatom Biostratigraphy of Subantarctic sediments, Deep Sea Drilling Project 71, Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, 21, 635–665, 1983. a, b, c

Cody, R. D., Levy, R. H., Harwood, D. M., and Sadler, P. M.: Thinking outside the zone: High-resolution quantitative diatom biochronology for the Antarctic Neogene, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 260, 92–121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.08.020, 2008. a, b, c, d

Cody, R. D., Levy, R. H., Crampton, J., Naish, T. R., Wilson, G., and Harwood, D. M.: Selection and stability of quantitative stratigraphic age models: Plio-Pleistocene glaciomarine sediments in the ANDRILL 1B drillcore, McMurdo Ice Shelf, Global Planet. Change, 96–97, 143–156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.05.017, 2012. a

Cook, C. P., Flierdt, T. V. D., Williams, T., Hemming, S. R., Iwai, M., Kobayashi, M., Jimenez-Espejo, F. J., Escutia, C., González, J. J., Khim, B. K., McKay, R. M., Passchier, S., Bohaty, S. M., Riesselman, C. R., Tauxe, L., Sugisaki, S., Galindo, A. L., Patterson, M. O., Sangiorgi, F., Pierce, E. L., Brinkhuis, H., Klaus, A., Fehr, A., Bendle, J. A., Bijl, P. K., Carr, S. A., Dunbar, R. B., Flores, J. A., Hayden, T. G., Katsuki, K., Kong, G. S., Nakai, M., Olney, M. P., Pekar, S. F., Pross, J., Röhl, U., Sakai, T., Shrivastava, P. K., Stickley, C. E., Tuo, S., Welsh, K., and Yamane, M.: Dynamic behaviour of the East Antarctic ice sheet during Pliocene warmth, Nat. Geosci., 6, 765–769, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1889, 2013. a

Cortese, G. and Gersonde, R.: Plio/Pleistocene changes in the main biogenic silica carrier in the Sothern Ocean, Atlantic Sector, Mar. Geol., 252, 100–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2008.03.015, 2008. a

Cox, E. J.: Pore occlusions in raphid diatoms – a reassessment of their structure and terminology with particular reference to members of the Cymbellales, Diatom, 20, 33–46, 2004. a

Crampton, J. S., Cody, R. D., Levy, R., Harwood, D., McKay, R., and Naish, T. R.: Southern Ocean phytoplankton turnover in response to stepwise Antarctic cooling over the past 15 million years, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 6868–6873, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1600318113, 2016. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h

Crosta, X., Pichon, J. J., and Burckle, L. H.: Application of modern analog technique to marine Antarctic diatoms: Reconstruction of maximum sea-ice extent at the Last Glacial Maximum, Paleoceanography, 13, 284–297, 1998. a

Crosta, X., Romero, O., Armand, L. K., and Pichon, J. J.: The biogeography of major diatom taxa in Southern Ocean sediments: 2. Open ocean related species, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 223, 66–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.03.028, 2005. a

Escutia, C., Brinkhuis, H., Klaus, A., and the Expedition 318 Scientists: Site U1361, Proceedings of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, 318, 1–56, https://doi.org/10.2204/iodp.proc.318.109.2011, 2011. a, b, c, d, e, f

Gersonde, R.: Taxonomy and Morphostructure of Late Neogene Diatoms from Maud Rise (Antarctic Ocean), Polarforschung, 59, 141–171, 1991. a

Gersonde, R. and Burckle, L. B.: 43. Neogene Diatom Biostratigraphy of ODP Leg 113, Weddell Sea (Antarctic Ocean), Proceedings of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, 113, 761–789, 1990. a, b, c, d, e

Gombos, A. M.: Paleogene and Neogene diatoms from the Falkland Plateau and Malvinas Outer Basin: Leg 36, Deep Sea Drilling Project, Initial Rep. Deep Sea, 36, 575–687, 1976. a, b, c, d, e

Harwood, D. M. and Maruyama, T.: Middle Eocene to Pleistocene Diatom Biostratigraphy of Southern Ocean Sediments from the Kerguelen Plateau, Leg 120, Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, 120 Scientific Results, 120, https://doi.org/10.2973/odp.proc.sr.120.160.1992, 1992. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Hillenbrand, C. D. and Cortese, G.: Polar stratification: A critical view from the Southern Ocean, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 242, 240–252, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.06.001, 2006. a

Iwai, M. and Winter, D.: Data Report: Taxonomic notes of Neogene diatoms from the western Antarctic Peninsula: Ocean Drilling Program Leg 178, Nature Communications, 178, 1–57, http://www-odp.tamu.edu/publications/178_SR/VOLUME/CHAPTERS/SR178_35.PDF (last access: 31 January 2019), 2002. a, b

Jansen, E. and Sjoholm, J.: Reconstruction of glaciation over the past 6 Myr from ice-borne deposits in the Norwegian Sea, Letters to Nature, 349, 600–603, 1991. a

Konfirst, M. A. and Scherer, R. P.: Low amplitude obliquity changes during the early Pliocene reflected in diatom fragmentation patterns in the ANDRILL AND-1B core, Mar. Micropaleontol., 82–83, 46–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2011.10.004, 2012. a

Konfirst, M. A., Kuhn, G., Monien, D., and Scherer, R. P.: Correlation of Early Pliocene diatomite to low amplitude Milankovitch cycles in the ANDRILL AND-1B drill core, Mar. Micropaleontol., 80, 114–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2011.06.005, 2011. a

Lamy, F., Winckler, G., Zarikian, C. A. A., Arz, H., Basak, C., Brombacher, A., Esper, O., Farmer, J., Gottschalk, J., Herbert, L., Iwasaki, S., Lawson, V., Lembke-Jene, L., Lo, L., Malinverno, E., Michel, E., Middleton, J., Moretti, S., Moy, C., Ravelo, A., Riesselman, C., Saavedra-Pellitero, M., Seo, I., Singh, R., Smith, R., Souza, A., Stoner, J., Venancio, I., Wan, S., Zhao, X., and McColl, N. F.: Site U1543, Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 383, edited by: Lamy, F., Winckler, G., Alvarez Zarikian, C. A., and the Expedition 383 Scientists, Dynamics of the Pacific Antarctic Circumpolar Current, https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.383.105.2021, 2021. a, b

Lisiecki, L. E. and Raymo, M. E.: A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records, Paleoceanography, 20, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004PA001071, 2005. a, b, c, d

Mann, D. G.: Sieves and Flaps: Siliceous Minutiae in the Pores of Raphid Diatoms, Proceedings of the 6th Diatom Symposium, Budapest, Hungary, 1–5 September 1980, 279–300, 1980. a

McCollum, D. W.: Diatom Stratigraphy of the Southern Ocean, Initial Rep. Deep Sea, 28, 515–571, 1975. a

McKay, R., Naish, T. R., Carter, L., Riesselman, C., Dunbar, R., Sjunneskog, C., Winter, D., Sangiorgi, F., Warren, C., Pagani, M., Schouten, S., Willmott, V., Levy, R., DeConto, R., and Powell, R. D.: Antarctic and Southern Ocean influences on Late Pliocene global cooling, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 6423–6428, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1112248109, 2012. a, b, c

Naafs, B. D., Hefter, J., and Stein, R.: Millennial-scale ice rafting events and Hudson Strait Heinrich(-like) Events during the late Pliocene and Pleistocene: A review, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 80, 1–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.08.014, 2013. a

Naish, T. R., Powell, R., Levy, R., Wilson, G., Scherer, R. P., Talarico, F., Krissek, L., Niessen, F., Pompilio, M., Wilson, T., Carter, L., DeConto, R., Huybers, P., McKay, R., Pollard, D., Ross, J., Winter, D., Barrett, P., Browne, G., Cody, R., Cowan, E., Crampton, J., Dunbar, G., Dunbar, N., Florindo, F., Gebhardt, C., Graham, I., Hannah, M., Hansaraj, D., Harwood, D., Helling, D., Henrys, S., Hinnov, L., Kuhn, G., Kyle, P., Läufer, A., Maffioli, P., Magens, D., Mandernack, K., McIntosh, W., Millan, C., Morin, R., Ohneiser, C., Paulsen, T., Persico, D., Raine, I., Reed, J., Riesselman, C., Sagnotti, L., Schmitt, D., Sjunneskog, C., Strong, P., Taviani, M., Vogel, S., Wilch, T., and Williams, T.: Obliquity-paced Pliocene West Antarctic ice sheet oscillations, Nature, 458, 322–328, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07867, 2009. a

Orsi, A. H., Whitworth, T., and Nowlin, W. D.: On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 42, 641–673, https://doi.org/10.1016/0967-0637(95)00021-W, 1995. a

Pagani, M., Liu, Z., LaRiviere, J., and Ravelo, A. C.: High Earth-system climate sensitivity determined from Pliocene carbon dioxide concentrations, Nat. Geosci., 3, 27–30, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo724, 2009. a

Patterson, M. O., McKay, R., Naish, T. R., Escutia, C., Jimenez-Espejo, F. J., Raymo, M. E., Meyers, S. R., Tauxe, L., Brinkhuis, H., Klaus, A., Fehr, A., Bendle, J. A., Bijl, P. K., Bohaty, S. M., Carr, S. A., Dunbar, R. B., Flores, J. A., Gonzalez, J. J., Hayden, T. G., Iwai, M., Katsuki, K., Kong, G. S., Nakai, M., Olney, M. P., Passchier, S., Pekar, S. F., Pross, J., Riesselman, C. R., Röhl, U., Sakai, T., Shrivastava, P. K., Stickley, C. E., Sugasaki, S., Tuo, S., Flierdt, T. V. D., Welsh, K., Williams, T., and Yamane, M.: Orbital forcing of the East Antarctic ice sheet during the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene, Nat. Geosci., 7, 841–847, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2273, 2014. a, b, c, d

Rea, D. K. and Schrader, H.: Late Pliocene onset of glaciation: Ice-rafting and diatom stratigraphy of North Pacific DSDP cores, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 49, 313–325, 1985. a

Riesselman, C. R. and Dunbar, R. B.: Diatom evidence for the onset of Pliocene cooling from AND-1B, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 369, 136–153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.10.014, 2013. a, b, c, d

Rohling, E. J., Foster, G. L., Grant, K. M., Marino, G., Roberts, A. P., Tamisiea, M. E., and Williams, F.: Sea-level and deep-sea-temperature variability over the past 5.3 million years, Nature, 508, 477–482, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13230, 2014. a, b

Romero, O. E., Armand, L. K., Crosta, X., and Pichon, J. J.: The biogeography of major diatom taxa in Southern Ocean surface sediments: 3. Tropical/Subtropical species, Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl., 223, 49–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.03.027, 2005. a

Round, F. E., Crawford, R., and Mann, D. G.: The Diatoms. Biology and morphology of the Genera, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 13 9780521363181, 1990. a

Sangiorgi, F., Bijl, P. K., Passchier, S., Salzmann, U., Schouten, S., McKay, R., Cody, R. D., Pross, J., van de Flierdt, T., Bohaty, S. M., Levy, R., Williams, T., Escutia, C., and Brinkhuis, H.: Southern Ocean warming and Wilkes Land ice sheet retreat during the mid-Miocene, Nat. Commun., 9, 317, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02609-7, 2018. a

Scherer, R. P., Hannah, M., Maffioli, P., Persico, D., Sjunneskog, C., Strong, C. P., Taviani, M., Winter, D., and the ANDrill-MIS Science Team: Palaeontologic Characterisation and Analysis of the AND-1B Core, ANDRILL McMurdo Ice Shelf Project, Antarctica, Terra Antartica, 14, 223–254, 2007. a, b

Schneider, C., Rasband, W., and Eliceiri, K.: NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis, Nat. Methods, 9, 671–675, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2089, 2012.

Schrader, H.-J.: Cenzoic diatoms from the Northeast Pacific, Initial Rep. Deep Sea, 18, 673–797, 1973. a

Schrader, H.-J.: Cenzoic Planktonic Diatom Biostratigraphy of the Southern Pacific Ocean, Initial Rep. Deep Sea, 35, 605–671, 1976. a, b, c, d, e

Seki, O., Foster, G. L., Schmidt, D. N., Mackensen, A., Kawamura, K., and Pancost, R. D.: Alkenone and boron-based Pliocene pCO2 records, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 292, 201–211, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.01.037, 2010. a

Shackleton, N. J., Backman, J., Zimmerman, H., Kent, D. V., Hall, M. A., Roberts, D. G., Schnitker, D., Baldauf, J. G., Desprairies, A., Homrighausen, R., Huddlestun, P., Keene, J. B., Kaltenback, A. J., Krumsiek, K. A., Morton, A. C., Murray, J. W., and Westberg-Smith, J.: Oxygen isotope calibration of the onset of ice-rafting and history of glaciation in the North Atlantic region, Nature, 307, 620–623, https://doi.org/10.1038/307620a0, 1984. a

Sjunneskog, C. and Winter, D.: A diatom record of late Pliocene cooling from the Ross Sea continental shelf, AND-1B, Antarctica, Global Planet. Change, 96-97, 87–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.01.013, 2012. a, b

Tauxe, L., Stickley, C. E., Sugisaki, S., Bijl, P. K., Bohaty, S. M., Brinkhuis, H., Escutia, C., Flores, J. A., Houben, A. J. P., Iwai, M., Jiménez-Espejo, F., McKay, R., Passchier, S., Pross, J., Riesselman, C. R., Röhl, U., Sangiorgi, F., Welsh, K., Klaus, A., Fehr, A., Bendle, J. A. P., Dunbar, R., Gonzàlez, J., Hayden, T., Katsuki, K., Olney, M. P., Pekar, S. F., Shrivastava, P. K., van de Flierdt, T., Williams, T., and Yamane, M.: Chronostratigraphic framework for the IODP Expedition 318 cores from the Wilkes Land Margin: Constraints for paleoceanographic reconstruction, Paleoceanography, 27, PA2214, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012PA002308, 2012. a

Tauxe, L., Sugisaki, S., Jiménez-Espejo, F., Escutia, C., Cook, C. P., van de Flierdt, T., and Iwai, M.: Geology of the Wilkes land sub-basin and stability of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet: Insights from rock magnetism at IODP Site U1361, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 412, 61–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.12.034, 2015. a, b, c

Taylor-Silva, B. I. and Riesselman, C. R.: Polar Frontal Migration in the Warm Late Pliocene: Diatom Evidence From the Wilkes Land Margin, East Antarctica, Paleoceanogr. Paleocl., 33, 76–92, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017PA003225, 2018. a, b, c, d, e, f

Warnock, J. P. and Scherer, R. P.: A revised method for determining the absolute abundance of diatoms, J. Paleolimnol., 53, 157–163, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-014-9808-0, 2014. a, b

Wilson, D. J., Bertram, R. A., Needham, E. F., van de Flierdt, T., Welsh, K. J., McKay, R. M., Mazumder, A., Riesselman, C. R., Jimenez-Espejo, F. J., and Escutia, C.: Ice loss from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet during late Pleistocene interglacials, Nature, 561, 383–386, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0501-8, 2018. a

Winckler, G., Lamy, F., Zarikian, C. A. A., Arz, H., Basak, C., Brombacher, A., Esper, O., Farmer, J., Gottschalk, J., Herbert, L., Iwasaki, S., Lawson, V., Lembke-Jene, L., Lo, L., Malinverno, E., Michel, E., Middleton, J., Moretti, S., Moy, C., Ravelo, A., Riesselman, C., Saavedra-Pellitero, M., Seo, I., Singh, R., Smith, R., Souza, A., Stoner, J., Venancio, I., Wan, S., Zhao, X., and McColl, N. F.: Site U1541, Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 383, edited by: Lamy, F., Winckler, G., Alvarez Zarikian, C. A., and the Expedition 383 Scientists, Dynamics of the Pacific Antarctic Circumpolar Current, https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.383.105.2021, 2021a. a, b

Winckler, G., Lamy, F., Zarikian, C. A. A., Arz, H., Basak, C., Brombacher, A., Esper, O., Farmer, J., Gottschalk, J., Herbert, L., Iwasaki, S., Lawson, V., Lembke-Jene, L., Lo, L., Malinverno, E., Michel, E., Middleton, J., Moretti, S., Moy, C., Ravelo, A., Riesselman, C., Saavedra-Pellitero, M., Seo, I., Singh, R., Smith, R., Souza, A., Stoner, J., Venancio, I., Wan, S., Zhao, X., and McColl, N. F.: Expedition 383 methods, Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 383, edited by: Lamy, F., Winckler, G., Alvarez Zarikian, C. A., and the Expedition 383 Scientists, Dynamics of the Pacific Antarctic Circumpolar Current, https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.383.105.2021, 2021b. a

Winter, D., Sjunneskog, C., and Harwood, D.: Early to mid-Pliocene environmentally constrained diatom assemblages from the AND-1B drillcore, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica, Stratigraphy, 7, 207–227, https://doi.org/10.2307/1484280, 2010. a

Woodard, S. C., Rosenthal, Y., Miller, K. G., Wright, J. D., Chiu, B. K., and Lawrence, K. T.: Antarctic role in Northern Hemisphere glaciation, Science, 346, 847–852, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255586, 2014. a

Zachos, J. C., Dickens, G. R., and Zeebe, R. E.: An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics, Nature, 451, 279–283, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06588, 2008. a

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Method and material

- Results

- Biostratigraphic and paleoceanographic applications

- Conclusions

- Appendix A

- Code availability

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Special issue statement

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Method and material

- Results

- Biostratigraphic and paleoceanographic applications

- Conclusions

- Appendix A

- Code availability

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Special issue statement

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement