the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Early to Middle Miocene in the North Sea Basin: proxy-based insights into environment, depositional settings and sea surface temperature evolution

Laura Kellner

Karen Dybkjær

Stefan Piasecki

Julie Fredborg

Francien Peterse

Erik S. Rasmussen

Manuel Vieira

Lígia Castro

Two Miocene successions from onshore Denmark (Sønder Vium, or Sdr. Vium, well) and offshore Norway (2/11-12S well) have been correlated using dinoflagellate cyst (dinocyst) biostratigraphy. This correlation provides a valuable opportunity to compare Early to Middle Miocene dinocyst assemblages and palynofacies across environmentally contrasting, yet time-equivalent, depositional settings in the North Sea Basin. Both successions were deposited during the Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO; ∼ 16.9–14.7 Ma), a prominent global warming phase within the Miocene. Our analyses integrate palynofacies and dinocyst biostratigraphy to reconstruct depositional settings, changes in the environment, and climatic conditions through the Burdigalian–Langhian interval. The palynofacies data, including palynomorph ratios ( index), indicate a distal marine setting in the offshore 2/11-12S well (low index, dominance of marine palynomorphs) and a more proximal marine setting at Sønder Vium (high index, higher terrestrial input). Dinocyst assemblages also mirror this environmental gradient. Oceanic to outer neritic taxa, such as Impagidinium spp. and Nematosphaeropsis spp., are abundant offshore but rare or absent onshore. Conversely, Homotryblium tenuispinosum, indicative of inner neritic settings, is present onshore but appears only once in the offshore well. The presence of thermophilic taxa (e.g., Melitasphaeridium choanophorum and Polysphaeridium zoharyi) in both wells during the late Burdigalian to early Langhian suggests sustained warm sea surface temperatures (SSTs) across the basin. Warm temperatures are supported by lipid-biomarker-derived (TEX86) SST estimates from the 2/11-12S well. Moreover, a distinct occurrence pattern of Polysphaeridium zoharyi is concurrent with the warmest SSTs during the late Burdigalian to early Langhian, corresponding to the MCO. The later appearance of cooler-water taxa, such as Habibacysta tectata, in the latest Langhian also coincides with a decrease in SST, indicating a climatic shift towards cooler conditions.

- Article

(26048 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(406 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The Miocene, spanning 23.03 to 5.33 Ma, is regarded as a “coolhouse” climate (Westerhold et al., 2020), paced by orbitally driven glaciation episodes in Antarctica, the Mi- events (e.g., Miller et al., 1991). Despite this, the Miocene was overall warmer than today's icehouse conditions. A significant climatic phase within this epoch was the Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO; ∼ 16.9–14.7 Ma), a period of sustained global warming followed by a gradual cooling trend that ultimately ushered in modern polar ice sheet expansion (Westerhold et al., 2020; Zachos et al., 2001). Importantly, the MCO was the last time in Earth's history when atmospheric CO2 levels were similar to today (Hönisch et al., 2023), making it a critical reference interval for future climate projections (Steinthorsdottir et al., 2020). The MCO was followed by the so-called Miocene Climatic Transition, a period of climatic cooling (e.g., Shevenell et al., 2004). The global climate deteriorated, leading to the onset of bipolar glaciation and setting the stage for the development of the modern icehouse climate system.

During the Early to Middle Miocene, present-day Denmark was covered by vegetation typical of warm and temperate but also humid to semi-humid conditions. Pollen and spores from that time interval suggest that broad-leaved deciduous forests and swamp forests were widespread (Larsson et al., 2011). In coastal swamp areas, Taxodium was the most prevalent genus, while the adjacent hardwood forests were dominated by Alnus, Ulmus, and Acer. In better-drained upland areas, species such as Magnolia, Castanea, and Juglans thrived (Larsson et al., 2011). The Early and Middle Miocene flora in Denmark included “exotic” vegetation, such as Sequoia (Redwood), Sabaloid palms, and Magnolia (see details in Śliwińska et al., 2024). The floristic turnover in Late Miocene northern Europe coincided with the establishment of the globally colder climate. In Denmark, e.g., in the Late Miocene, Sabal palms disappeared, and Taxodium declined significantly (Larsson et al., 2011).

Despite growing interest in the MCO, North Sea climate records from this interval remain limited. Only one study has explored SST evolution across the MCO in the Danish North Sea (Herbert et al., 2020). A few studies cover the larger northern North Atlantic–Nordic Seas region (Sangiorgi et al., 2021; Herbert et al., 2016). Many of these records cover either the warmest part of the MCO or the subsequent period of cooling; e.g., they do not cover the pre-MCO interval. The only existing SST record across the MCO from the Danish North Sea is based on the distributions of alkenones (Herbert et al., 2020) in the Sønder Vium (Sdr. Vium) well. This well is, so far, the most northerly located site revealing SST evolution across the MCO, covering both pre- and post-MCO. The temperature records suggest that, in the warmest part of the MCO, SST was up to 20 °C higher than present (Herbert et al., 2020), notably, within the range of summer (warmest mean month) temperature for the Miocene derived from the pollen and spore record (Śliwińska et al., 2024).

While climatic records are scarce, a robust biostratigraphic framework has been developed for the central and eastern North Sea Basin through decades of palynological and micropalaeontological research studies (e.g., Powell, 1992; Laursen and Kristoffersen, 1999; Dybkjær and Piasecki, 2010; Munsterman and Brinkhuis, 2013; King et al., 2016; Sheldon et al., 2025). Building on this framework, palynofacies (organic sedimentary particles, e.g., pollen, spores, dinocysts, fungal spores) analysis is a proven effective tool for reconstructing past environmental changes (Tyson, 1995; De Vernal, 2009; Dybkjær et al., 2019). The composition of organic sedimentary particles is influenced by e.g., the distance from the shoreline, freshwater input, depositional energy, and organic matter source (Tyson, 1995; De Vernal, 2009). Analyses of palynofacies aid in reconstructing the relative distance from the land and the depositional energy by assessing the distribution of organic constituents (e.g., Dybkjær, 2004a; Rasmussen and Dybkjær, 2005; Rasmussen et al., 2006; Śliwińska et al., 2014; Dybkjær et al., 2019). Another valuable method for reconstructing (past) surface water conditions is dinocyst assemblages. Dinoflagellates are sensitive to changes in various environmental parameters such as temperature, salinity, nutrients, and light availability (e.g., Dale, 1996; Head, 1996; Zonneveld et al., 2013), making dinocysts important proxies in palaeoenvironmental and palaeoclimatic research. However, dinoflagellates respond to multiple environmental drivers simultaneously, so interpreting their fossil assemblages can be complex. Isolating the effects of individual environmental parameters in the fossil record – such as separating temperature influences from salinity – requires a well-constrained environmental framework, for example, studying dinocyst assemblages from the same time interval but from different environmental settings. Such studies are, however, very limited (e.g., Pross and Schmiedl, 2002).

This study aims to bridge the gap between the climatic and environmental reconstruction of the Miocene succession in the North Sea and improve the understanding of dinocysts as palaeoenvironmental proxies. To achieve these aims, we integrate palynofacies and dinocyst assemblage analysis across the MCO using sediment cores from two wells penetrating two different depositional settings:

-

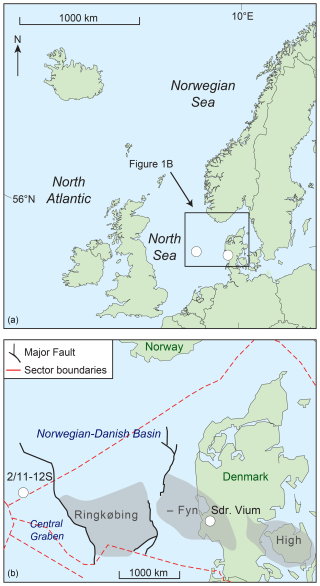

The Sdr. Vium well (DGU nr 102.948) – located onshore Denmark (Fig. 1), in the western part of Jylland. The well was drilled in 2002 and has been extensively studied for sedimentology, palynology, and organic geochemistry (e.g., Rasmussen et al., 2010; Dybkjær and Piasecki, 2010; Larsson et al., 2011; Anthonissen, 2012; Herbert et al., 2020; Śliwińska et al., 2024).

-

The 2/11-12S well – located in the central North Sea (Fig. 1), in the southernmost part of the Norwegian sector. The well was drilled in 2019. Publicly available data are limited to an integrated biostratigraphic framework, including dinocyst stratigraphy (Sheldon et al., 2025).

Figure 1Location of the Sdr. Vium and 2/11-12S wells and major structural elements in the greater North Sea area (modified from Śliwińska, 2019).

The Miocene succession in the Sdr. Vium well was deposited relatively close to the coastline, with the water depth fluctuating between 0 and 200 m (e.g., Śliwińska et al., 2024). In contrast, the 2/11-12S well is situated in the central North Sea Basin, far from the coastline, representing a more distal depositional setting. The correlation between wells is based on key dinocyst bioevents (defined by Dybkjær and Piasecki, 2010) and enables the unique opportunity to compare Early to Middle Miocene dinocyst assemblages from time-equivalent, yet environmentally distinct, depositional settings. Our study provides the reconstruction of the depositional environment history and climatic conditions during the MCO.

Additionally, we applied a palaeothermometer, TetraEther indeX of tetraethers consisting of 86 carbon atoms (TEX86) (Schouten et al., 2002), on the 2/11-12S well to trace changes in the surface water temperature independently from the dinocyst assemblages. Although the 2/11-12S well contains hydrocarbons, the isoprenoid GDGTs (isoGDGTs) used in TEX86 analysis remain stable and largely unaffected by thermal overprinting from oil. Thus, TEX86 offers a viable approach for estimating SSTs at this site and complements the palynological data.

2.1 Geological setting and palaeoenvironment of the North Sea

The Cenozoic evolution of the North Sea Basin was primarily driven by thermal subsidence following the cessation of Mesozoic rifting (Ziegler, 1990; Knox et al., 2010). Although this thermal relaxation led to a generally steady pattern of basin subsidence, it was intermittently disrupted by the reactivation of pre-existing fault systems. These tectonic movements uplifted former graben structures and reactivated salt structures, significantly influencing sediment routing, shoreline distribution, and depositional trends (Liboriussen et al., 1987; Mogensen and Jensen, 1994; Rasmussen, 2009, 2013). The evolution of the Fennoscandian hinterland played a key role in the infilling of the eastern North Sea throughout the Cenozoic. During the Miocene, extensive river systems drained this region, with estimated discharges around 30 000 m3 s−1. These rivers initially exhibited braided morphologies, transitioning to meandering systems from the Burdigalian onwards. At their outlets, wave-dominated delta complexes formed (Rasmussen et al., 2010). The position of the North Sea within the prevailing westerly wind belt further influenced sediment transport. East of the main delta systems, sands were redistributed by longshore drift, accumulating in spit and barrier complexes. In contrast, fine-grained sediments were transported westward by slope-parallel bottom currents and deposited as contourites in deeper marine settings (Rasmussen et al., 2025). Water depths in the central North Sea during the Miocene reached up to 700 m (Rasmussen et al., 2025). The Early to Middle Miocene delta systems in the eastern North Sea were largely controlled by eustatic sea-level fluctuations, resulting in three major regressive–transgressive cycles (Rasmussen et al., 2025). Concurrent with the regressive part of the youngest of the three cycles, diatomite was deposited in the central parts of the basin. A major marine transgression during the Middle Miocene, linked to tectonic reorganization in northwestern Europe, led to the drowning of these deltas (Ziegler, 1990; Rasmussen, 2004). Delta progradation resumed in the Late Miocene, continuing into the Pliocene, as sediment supply from Fennoscandia increased once more (Rasmussen et al., 2025).

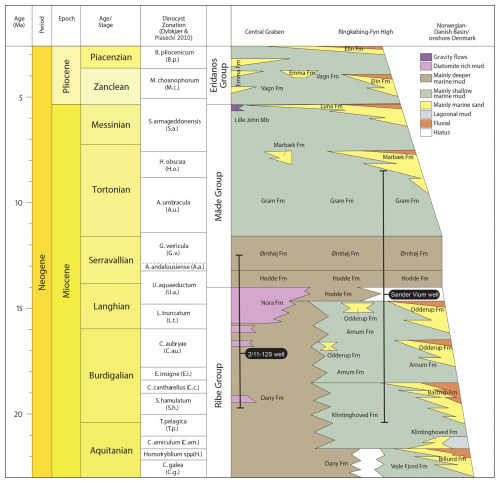

2.2 Miocene sedimentary succession in the eastern North Sea (Sdr. Vium well, onshore Denmark)

The Miocene succession onshore Denmark comprises a series of sedimentary deposits subdivided into 11 lithostratigraphic units (Rasmussen et al., 2010, 2025). In the Early Miocene, three sand-rich formations, the Billund, Bastrup, and Odderup formations, were deposited in fluvio-deltaic depositional environments (Fig. 2). These units are interfingered with marine deposits, specifically the Vejle Fjord, Klintinghoved, and Arnum formations, which reflect periods of marine transgression. In the westernmost part of the Danish sector of the North Sea, the marine mud-rich Klintinghoved and Arnum formations interfinger with the clay- and diatomite-rich sediments of the newly defined Dany and Nora formations, indicating lateral variations in depositional environments (Rasmussen et al., 2025). Deposition of the Odderup, Arnum, and Nora formations continued into the early Middle Miocene, until the subsidence of the North Sea Basin and the resulting transgression of the fluvial deltaic systems gave way to more widespread marine conditions. This transition is marked by the onset of deposition of the mud-rich Hodde and Ørnhøj formations (Rasmussen et al., 2010, 2025). The Upper Miocene was characterized by the marine Gram Formation, which reflects a continued fully marine transgressive regime. This was followed by a renewed phase of fluvio-deltaic sedimentation represented by the Marbæk and Luna formations (Rasmussen et al., 2010, 2025), indicating a reestablishment of a more proximal depositional setting.

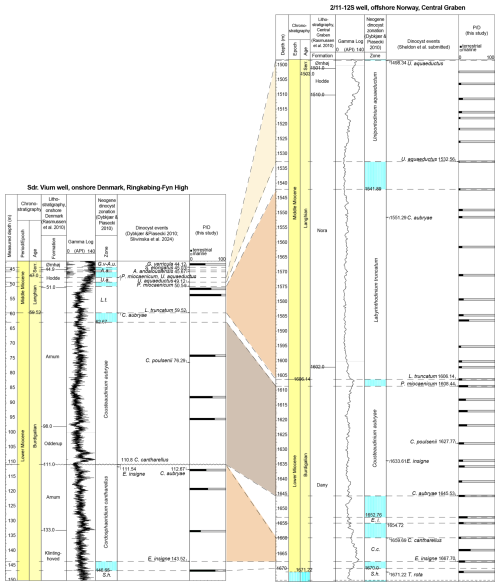

Figure 2Location and investigated core intervals of the Sdr. Vium and 2/11-12S wells plotted against the new Danish lithostratigraphic framework for the Neogene (adapted from Rasmussen et al., 2025).

The stratigraphic framework of the Danish Miocene succession is underpinned by a combination of sequence stratigraphy (e.g., Michelsen et al., 1995, 1999; Rasmussen, 1996, 2004; Sørensen et al., 1997; Gregersen, 1998; Clausen et al., 1999; Rasmussen and Dybkjær, 2005; Rasmussen et al., 2006; Dybkjær, 2004a), strontium isotope stratigraphy (Howarth and McArthur, 1997; Eidvin and Rundberg, 2001, 2007; Eidvin et al., 2014), and biostratigraphy (see more in Dybkjær and Piasecki, 2010; Śliwińska et al., 2024). This integrated framework extends into the central North Sea, supporting regional correlations. A key contribution to the biostratigraphic framework of the Danish Miocene was made by Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010), who provided a dinocyst zonation for the Danish onshore and offshore Neogene. Their zonation is based on extensive palynological analysis from onshore wells, outcrops, and offshore wells. Crucial to this study was the Sdr. Vium well, which penetrates the most complete Miocene succession onshore Denmark, located in Jylland, western Denmark (Fig. 1). The Sdr. Vium well spans an interval from the Burdigalian to the Tortonian (Rasmussen et al., 2010; Fig. 2).

2.3 Miocene succession in the central North Sea (2/11-12S well)

The 2/11-12S well is located in the Norwegian sector of the central North Sea (Fig. 1) and penetrates the upper part of the Lark Formation. The upper Lark Formation in this well was deposited during the final phase of shoreline progradation from the southern Scandes (Scandinavian Mountain range) and is time-equivalent to the Odderup Formation onshore Denmark (Sheldon et al., 2025; Rasmussen et al., 2025).

The Lark Formation, part of the Hordaland Group, extends across the central part of the North Sea Basin and is predominantly composed of different mudstone intervals (Schiøler et al., 2007). Within the Lower to Middle Miocene succession of the Lark Formation in the Central Graben, layers enriched by biogenic silica – comprising diatoms, radiolarians, and sponge spicules – have been identified (Sulsbrück and Toft, 2018; Sheldon et al., 2018, 2025; Rasmussen et al., 2025). Recently, two new lithostratigraphic units equivalent with this succession have been proposed for the Danish sector of the central North Sea: the Lower Miocene Dany Formation, consisting of mud and silt deposits, and the Middle Miocene Nora Formation, characterized by high silica and diatomite content (Rasmussen et al., 2025; Fig. 2). A new study by Sheldon et al. (2025) provides a multidisciplinary biostratigraphic framework for the Miocene succession in the southern Norwegian sector of the North Sea. This framework integrates data from dinocysts, microfossils, calcareous nannofossils, diatoms, and silicoflagellates. Notably, the 2/11-12S well – one of only two fully cored wells in the area – served as a key reference section for establishing this framework.

3.1 Palynology

3.1.1 Sdr. Vium and 2/11-12S wells

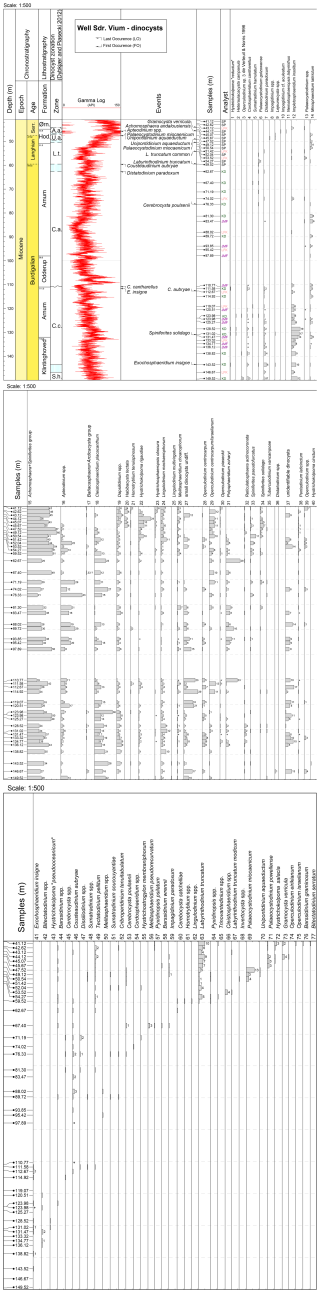

A total of 45 samples were collected from the Danish Sdr. Vium well, spanning depths from 149.52 to 41.12 m, and processed for palynological analysis. The samples cover four of the Miocene formations, Klintinghoved Formation (up to 132 m), Arnum Formation (132.0 to 111.0 m and 98.0 to 51.0 m), Hodde Formation (51.0 to 44.9 m), and Ørnhøj Formation (44.9 to 40.0 m), spanning the Lower Miocene to Middle Miocene (Figs. 2 and 3). The Odderup Formation consists of loose sand and was not cored. The studied interval covers the following dinocyst zones: Sumatradinium hamulatum (the uppermost part), Cordosphaeridium cantharellus, Cousteaudinium aubryae, Labyrinthodinium truncatum, Unipontidinium aquaeductum, and Achomosphaera andalousiensis zones sensu Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010). In this study, we applied the stratigraphic framework of the Sdr. Vium well following Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010) and Śliwińska et al. (2024). The first sample set (25 samples, analysed for dinocysts by Stefan Piasecki and Karen Dybkjær: SP and KD in Fig. 3) formed the basis of the Neogene dinocyst zonation published in Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010), which focused on first and last occurrences of key taxa. However, raw abundance data and recorded taxa were not previously published. An additional set of 20 samples (analysed by Julie Fredborg and Laura F. Kellner: JMF and LFK in Fig. 3) was generated to increase the resolution of the studied succession. Based on the new sample set, the dinocyst-derived stratigraphic model for the interval from 115 to 22 m was updated in Śliwińska et al. (2024). In the current study, we focus on the environmental changes recorded in the dinocyst assemblages from the full dataset available for the well. Additionally, to elucidate changes in the depositional environments, a palynofacies analysis was performed on 10 samples (analysed by LFK under the supervision of KD; Fig. 4), examining the distribution of various palynomorph assemblages and calculating the index ( index) throughout the succession.

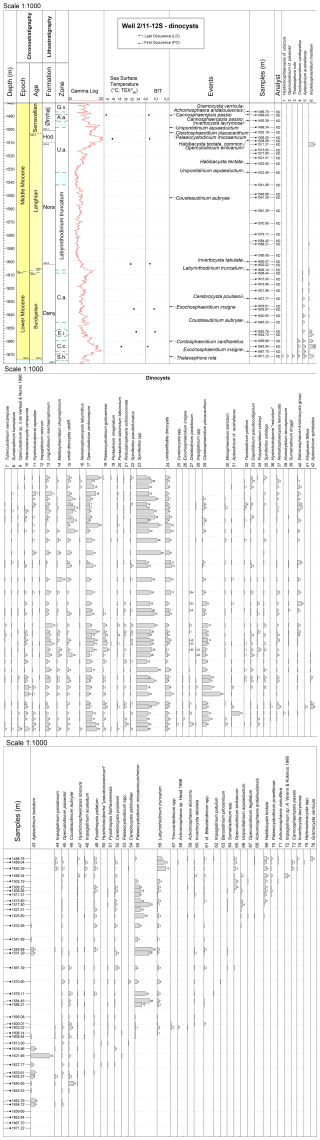

Figure 3Range chart showing the relative abundance (%) of all recorded dinocysts (in situ) in the Sdr. Vium well. Only when the abundance of a specific taxon/genus is > 1 % is the percentage value provided as a number. The distribution of dinocysts is arranged according to the first occurrence (FO). Hystrichokolpoma reductum and Hystrichokolpoma pseudooceanicum were invalidly published by Zevenboom (1995) and therefore the names are in quotation marks. Data are plotted against the dinocyst zones defined by Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010) and onshore Danish lithostratigraphy (Rasmussen et al., 2010). Biozone abbreviations: S.h., Sumatradinium hamulatum; C.c., Cordosphaeridium cantharellus; C.a., Cousteaudinium aubryae; L.t., Labyrinthodinium truncatum; U.a., Unipontidinium aquaeductus; A.a., Achomosphaera andalousiensis. +: taxa observed outside counting; ?: questionable. Lithostratigraphy column: Ørn – Ørnhøj; Hod.: Hodde.

A total of 40 samples were analysed by KD from five cored intervals of the 2/11-12S well (located in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea), covering a depth range from 1671.22 to 1486.78 m (Fig. 5). All samples were also analysed for palynofacies (Fig. 6). The studied succession spans the lower Burdigalian to middle Serravallian and includes the following dinocyst biozones (sensu Dybkjær and Piasecki, 2010), as documented by Sheldon et al. (2025): Sumatradinium hamulatum, Cordosphaeridium cantharellus, Exochosphaeridium insigne, Cousteaudinium aubryae, Labyrinthodinium truncatum, Unipontidinium aquaeductum, and Achomosphaera andalousiensis.

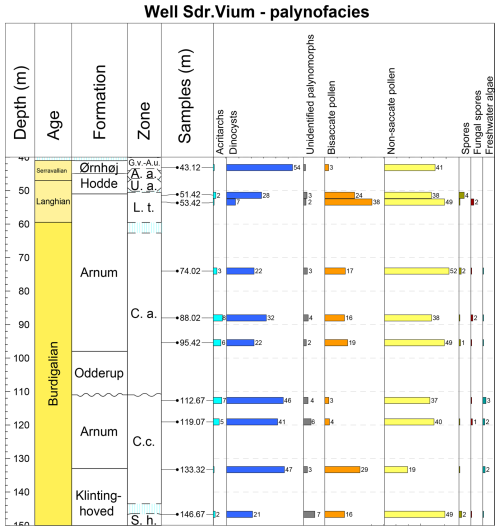

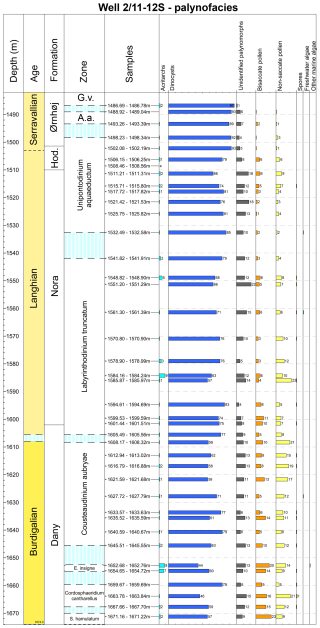

Figure 4Range chart showing the relative abundance (%) of all palynomorphs in the Sdr. Vium well. Data are plotted against the dinocyst zones defined by Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010) and onshore Danish lithostratigraphy (Rasmussen et al., 2010). Biozone abbreviations: S.h., Sumatradinium hamulatum; C.c., Cordosphaeridium cantharellus; C.a., Cousteaudinium aubryae; L.t., Labyrinthodinium truncatum; U.a., Unipontidinium aquaeductus; A.a., Achomosphaera andalousiensis; G.v., Gramocysta verricula.

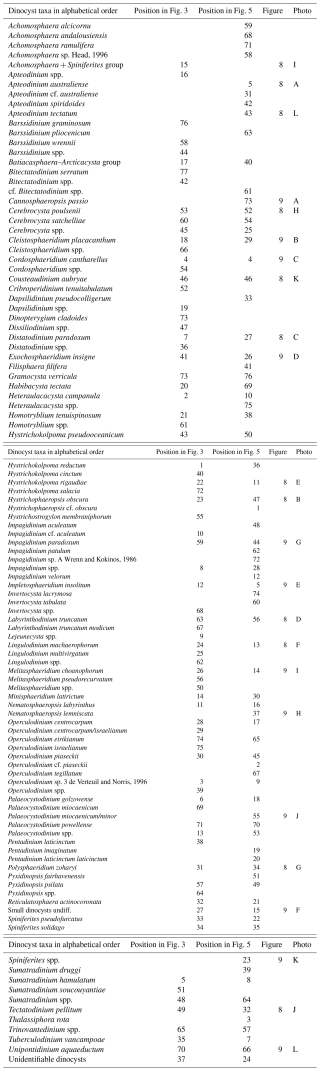

All samples presented in this study were processed at the Palynological Laboratory of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) in Copenhagen, following the internal preparation methods: sediment samples were dried and manually crushed. Approximately 20 g of sediment (< 2 mm particles) from each sample was used for the preparation of palynological samples. Applied treatment included HCL, HF, neutralization, brief oxidation with HNO3 and KOH, heavy liquid separation, and filtering on a nylon screen with an 11 µm mesh size. Residues were mounted on glass slides with glycerine jelly. For palynofacies analysis, organic residue filtered on 11 µm mesh size was used. Dinocyst analysis was carried out on slides where organic residua were filtered on a 20 µm nylon net. For age-diagnostic dinocysts, we determine the first occurrence (FO) and the last occurrence (LO), as shown in Figs. 3 and 5. A complete list of all registered dinocysts, along with their position in Figs. 3 and 5, is shown in Appendix A (Table A1). All slides are stored at GEUS.

Figure 5Range chart showing the relative abundance (%) of all recorded dinocysts (in situ) in the 2/11-12S well. Only when the abundance of a specific taxon/genus is > 1 % is the percentage value provided as a number. The distribution of dinocysts is arranged according to the first occurrence (FO). Data are plotted against the dinocyst zones defined by Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010) and onshore Danish lithostratigraphy (Rasmussen et al., 2025). Biozone abbreviations: S.h., Sumatradinium hamulatum; C.c., Cordosphaeridium cantharellus; E.i., Exochosphaeridium insigne; C.a., Cousteaudinium aubryae; U.a., Unipontidinium aquaeductus; A.a., Achomosphaera andalousiensis; G.v., Gramocysta verricula. +: taxa observed outside counting; ?: questionable.

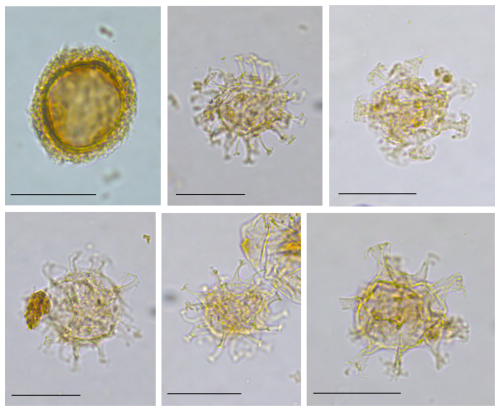

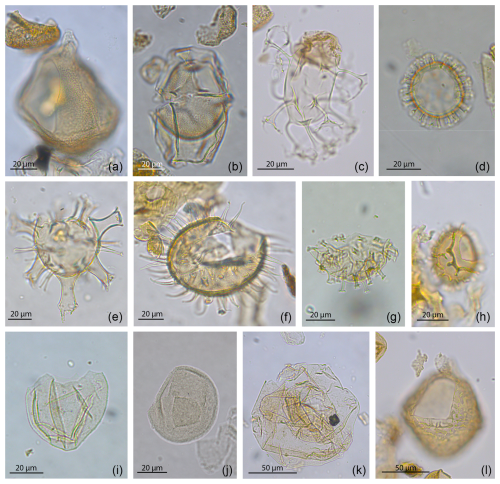

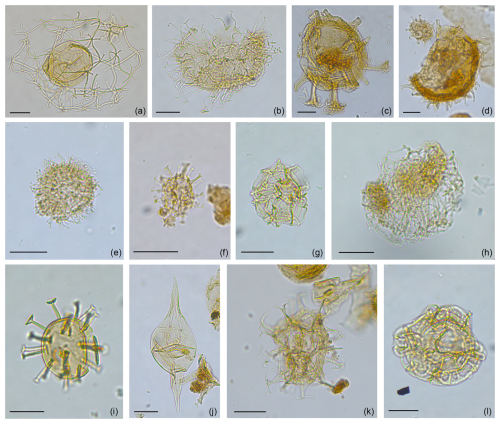

Microscopic examination was conducted at GEUS using a Leica DM 2000 transmitted light microscope with 400× and 1000× magnification. Images were captured using a Leica DFC295 camera.

3.1.2 Palynomorph counting method

For dinocyst analysis, a minimum of 200 specimens were identified per sample to species or genera level, making a total of 25 177 specimens counted in both wells. Dinocysts lacking diagnostic features were grouped as “unidentified dinocysts”. Additionally, the group named here “small dinocysts undiff.” includes small palynomorphs (< 30 µm) considered to be dinocysts. These palynomorphs consist of various morphotypes (see Appendix B) which have an outline typical for dinocysts, but we were not able to observe key diagnostic features, e.g., the archeopyle type (see Appendix B for more photos). Therefore, with no clearly visible features allowing at least genus identification, we decided to group them for simplicity. Taxonomic nomenclature for dinocysts identified to genus and species level follows Williams et al. (2017). Raw dinocyst data from both wells are provided in the Supplement data files. The relative abundance of dinocyst taxa for Sdr. Vium well is shown in Fig. 3, and that of the 2/11-12S well is shown in Fig. 4. Notably, heterotrophic dinocysts have hitherto rarely been recorded in the Danish Miocene and consist mainly of the genus Palaeocystodinium. This could be due to the oxidation step in our preparation methods, which may affect the preservation of heterotrophic dinocysts (e.g., Zonneveld et al., 2010).

For palynofacies analysis, palynomorphs from both wells (10 samples from the LFK-sample set from the Sdr. Vium well and all samples from the 2/11-12S well) were counted and assigned to one of eight categories: (1) non-saccate pollen, (2) bisaccate pollen, (3) spores, (4) fungal spores, (5) freshwater algae, (6) acritarchs, (7) dinocysts, (8) unidentified palynomorphs (see Dybkjær et al., 2019, for in-depth information on the methods, subdivision, the “freshwater algae” category, and photos of the categories). A minimum of 300 particles were counted per slide/sample. Identifiable fragments were counted as single particles. The last category contains all degraded particles and particles that are not possible to assign to any other group. The raw palynofacies data for each of the palynomorph categories are shown in the Supplement data file. The relative abundance of palynomorphs in the Sdr. Vium well is shown in Fig. 4,, and that of the the 2/11-12S well is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6Range chart showing the relative abundance (%) of all palynomorphs in the 2/11-12S well. Data are plotted against the dinocyst zones defined by Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010) and onshore Danish lithostratigraphy (Rasmussen et al., 2025). Biozone abbreviations: S. hamulatum, Sumatradinium hamulatum; E. insigne, Exochosphaeridium insigne; A.a., Achomosphaera andalousiensis; G.v., Gramocysta verricula.

3.1.3 index

The index expresses the ratio between terrestrial and marine palynomorphs (Versteegh, 1994; McCarthy and Mudie, 1998; Donders et al., 2009). It can be used to determine the relative proximity to the coastline (e.g., McCarthy et al., 2003; Dybkjær et al., 2019). Terrestrial palynomorphs (P) include non-saccate pollen, spores, fungal spores, and freshwater algae, whereas marine palynomorphs are represented by dinocysts only (D). These terrestrial palynomorphs are recorded in the highest abundances in nearshore marine settings (e.g., Mudie, 1982; Dybkjær et al., 2019). A low index value indicates high marine influence, meaning that there is less proximity to land, while a high index value reflects higher terrestrial influence and higher proximity to land (e.g., McCarthy et al., 2003). The index was calculated as follows:

Bisaccate pollen palynomorphs are not included in the index estimates due to their ubiquitous presence in all types of environments: marine, terrestrial, and lacustrine. The index values for both wells are shown in Fig. 7. Raw data are included in the Supplement data file.

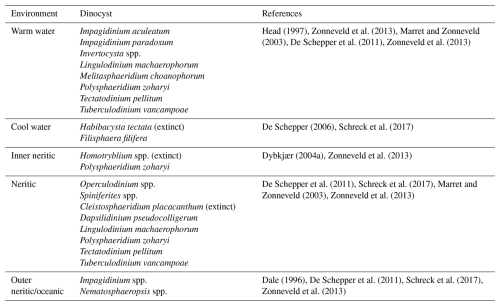

3.1.4 Dinocysts and other palynomorphs as environmental indicators

Several studies (e.g., Dale, 1996; Pross and Brinkhuis, 2005) affirm that organic-walled dinocysts are present across a wide range of aquatic environments, including marine and brackish or freshwater settings. Dinocysts are highly sensitive to changes in surface water conditions, such as light availability, salinity, sea surface temperature, and nutrient supply, making them valuable proxies for reconstructing past environmental changes (e.g., Dale, 1996; Head, 1996; De Schepper, 2006, 2009; Quaijtaal et al., 2014; Boyd et al., 2018; Śliwińska, 2019; Vieira and Jolley, 2020; Vieira et al., 2022). The environmental affinities of modern dinocysts are well documented (e.g., Zonneveld et al., 2013; Head, 1996). Several modern dinocysts, such as Lingulodinium machaerophorum and Polysphaeridium zoharyi (see Table 1), existed before the Miocene, so their presence or absence or abundance variations in the geological archives can rather be directly applied to trace past changes in the environment. However, a number of the Miocene dinocysts (e.g., Homotryblium spp.) are now extinct, and the preferential habitat of these dinocysts needs to be extrapolated. This is done by e.g., analysing their co-occurrence with other taxa of known ecological preferences, palaeogeographical context, and associated geochemical proxies (e.g., stable isotopes, biomarkers), allowing a reconstruction of their likely environmental tolerances and habitat conditions.

In this study, we follow the environmental affinities of dinocyst taxa suggested in previous studies by e.g., Head (1994, 1996, 1997), Dale (1996), Dybkjær (2004b), De Schepper et al. (2009), De Schepper et al. (2011), Zonneveld et al. (2013), Marret and Zonneveld (2003), Schreck et al. (2013), and Schreck et al. (2017).

3.2 Organic geochemistry

Seven sediment samples (subsamples of the palynological samples) distributed across the entire cored interval of the 2/11-12S well were processed for biomarker analysis at GEUS (Fig. 5). Samples were collected from the interval between 1672.00 to 1491.61 m. Each sediment sample was freeze-dried and mechanically powdered. Sediment samples (10–13 g) were extracted with a mixture of dichloromethane (DCM) and methanol (MeOH) (9:1; ) using the Milestone ETHOS X Advanced Microwave Extraction System. Extraction was performed during a 10 min ramp to 70 °C (1000 W), a 10 min hold at 70 °C (1000 W), and a 20 min cooling phase. Supernatants were collected, and the remaining sample was rinsed with DCM:MeOH (9:1, ) at least five times to maximize lipid extraction. The total lipid extracts (TLEs) were concentrated using the TurboVap evaporator system. TLEs were separated into three fractions over a 4 cm silica column by elution with hexane (saturated fraction), hexane:DCM (1:1 ; neutral fraction), and DCM:MeOH (1:1 ; polar fraction).

The neutral fractions (containing alkenones) were analysed on a Hewlett Packard gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a CP-sil 5CB fused silica column coupled to a flame ionization detector (FID) and helium as a carrier gas at Utrecht University.

The polar fractions (containing GDGTs) were re-dissolved in hexane:isopropanol (99:1, ) and filtered using a 0.45 µM PTFE filter. GDGTs were analysed using an Agilent 1260 Infinity ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatograph coupled to an Agilent 6130 single quadrupole mass spectrometer (UHPLC-MS) at Utrecht University, with instrument and method settings according to Hopmans et al. (2016).

The GDGT distributions were tested for non-thermal overprints using dedicated indices established in the literature (see Bijl et al., 2025 for overview) prior to translating the TEX86 into temperature using an SST calibration (TEX; (Schouten et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2010). Additionally, the branched and isoprenoid tetraether (BIT) index is used here as a proxy for the relative input of soil organic matter into the marine environment. Calculations of GDGT relative abundances and indices for samples from the 2/11-12S well are provided in the Supplement data file.

4.1 The Sdr. Vium well (onshore Denmark)

4.1.1 Diversity and abundance of dinocysts

In the Sdr. Vium well, we identified 23 genera, 51 species, and 1 subspecies of dinocysts (Fig. 3). The preservation of the dinocysts is moderate to good. The most abundant dinocyst species are Achomosphaera + Spiniferites spp. (19 %–60 %), Apteodinium spp. (< 1 %–43 %), Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum (< 1 %–36 %), Dapsilidinium spp. (< 1%–9 %), Hystrichokolpoma rigaudiae (< 1%–24 %), Impletosphaeridium insolitum (< 1 %–19 %), Lingulodinium machaerophorum (< 1 %–12 %), Operculodinium centrocarpum (< 1 %–13 %), and Polysphaeridium zoharyi (< 1%–29 %); see Fig. 3 for details. The genera Achomosphaera + Spiniferites and Apteodinium spp. and the species Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum dominate throughout the entire studied interval. Selected dinocyst taxa from the well are shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8Photos of selected taxa from the Sdr. Vium well (onshore Denmark). (a) Apteodinium cf. australiense, (b) Hystrichosphaeropsis obscura, (c) Distatodinium paradoxum, (d) Labyrinthodinium truncatum, (e) Hystrichokolpoma rigaudiae , (f) Lingulodinium machaerophorum, (g) Polysphaeridium zoharyi, (h) Cerebrocysta poulsenii, (i) Batiacasphaera + Arcticacysta group spp., (j) Tectatodinium pellitum, (k) Cousteaudinium aubryae, (l) Apteodinium tectatum.

The stratigraphically diagnostic dinocyst events recognized in our dataset include the LO of Cordosphaeridium cantharellus at 111.00 m, the FO of Cousteaudinium aubryae at 110.77 m, the FO of Labyrinthodinium truncatum at 59.54 m (Fig. 3a), the FO of Unipontidinium aquaeductum at 49.12 m with the LO at 47.52 m, and the FO of Achomosphaera andalousiensis at 45.67 m (Fig. 3). The rare occurrence of reworked species in the Sdr. Vium well suggests only minor reworking (Supplement data file).

Several neritic taxa (see details in Table 1) are present in the Sdr. Vium well, including Operculodinium spp., Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum, and Dapsilidinium pseudocolligerum (Fig. 3). The outer neritic/oceanic genus Nematosphaeropsis spp. makes a single occurrence (at 45.67m) at the top of the studied succession. The inner neritic genus Homotryblium occurs throughout the succession in low abundance, represented mainly by Homotryblium tenuispinosum (Fig. 3).

Warm-water-tolerant species (Table 1), such as Lingulodinium machaerophorum, Melitasphaeridium choanophorum, Polysphaeridium zoharyi, and Impagidinium paradoxum, are observed throughout the succession (Fig. 3). While L. machaerophorum and M. choanophorum are present in nearly every sample, P. zoharyi has its last persistent occurrence at 52.04 m. I. paradoxum appears only sporadically from 50.54 to 45.67 m. The cool-water-tolerant species (Table 1) Habibacysta tectata has an FO at 49.12 m (Fig. 3).

4.1.2 Palynofacies and index

The palynofacies data show variability in each group throughout the studied succession (Fig. 4). In the lower part of the succession (146.67 to 133.32 m), the relative abundance of non-saccate pollen decreased from 49 % to 19 %. In contrast, the abundance of dinocysts increased from 21 % to 47 %. At a depth of 119.07 m, both groups reach similar values: the non-saccate increases to 40 %, and the dinocysts decrease to 41 %. At 112.67 m, there is a small increase to 46 % in dinocyst relative abundance, coinciding with a decrease in non-saccate pollen to 37 %. Between 110 and 98 m, there is a core gap due to the presence of the loose or unconsolidated sand deposits of the Odderup Formation. The interval from 95.42 to 51.42 m is characterized by a higher terrestrial input than the interval (146.67 to 112.67 m) below the core gap, where the relative abundances of the non-saccate pollen range between 38 % and 52 % and the dinocyst abundances range between 7 % and 32 %. The topmost sample at 43.12 m, representing the basal part of the Ørnhøj Formation, is characterized by the highest relative abundance of dinocysts (54 %) recognized in any of the previously analysed samples. Overall, with the exception of the lower part of the Arnum Formation and the Ørnhøj Formation, which are dominated by dinocysts, the succession is dominated by non-saccate pollen.

The relative abundance of bisaccate pollen varies between 3 % and 38 % throughout the succession (Fig. 4). Spores and fungal spores vary from < 1 % to 4 % and < 1 % to 2 %, respectively. Acritarchs are present in every sample with an abundance variation between < 1% and 8 %, having the highest relative abundance in the middle part of the succession (119.07 to 88.02 m). Freshwater algae only appear in the lower and middle part of the succession (146.67 to 74.02 m), varying from < 1 % to 3 % (Fig. 4).

The index (Fig. 7) decreases in the lowest part of the succession (146.67–133.32 m), from 71 % to 31 %. From 133.32 to 53.42 m, the index increases from 31 % to 88 %. In the uppermost part of the succession (53.42 to 43.12 m), the index decreases significantly from 88 % to 43 %. The index closely follows the trends observed in the dinocysts and non-saccate pollen (Figs. 4 and 7).

4.2 The 2/11-12S well (central North Sea)

4.2.1 Diversity and abundance of dinocysts

In the 2/11-12S well, we identified 8 genera, 64 species, and 1 subspecies of dinocysts (Fig. 5), with moderate to good preservation. Selected dinocysts from the well are shown in Fig. 9. The most commonly occurring dinocyst taxa are Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum (1 %–34 %), Lingulodinium machaerophorum (1 %–12 %), Operculodinium centrocarpum (3 %–23 %), Palaeocystodinium miocaenicum/minor (2 %–30 %), Spiniferites spp. (17 %–45 %), and the “small dinocysts undiff.” (1 %–15 %); Fig. 5. The genus Spiniferites and the species Operculodinium centrocarpum and Lingulodinium machaerophorum are abundant throughout the studied interval. Palaeocystodinium miocaenicum/minor only appears from 1608.84 to 1500.54 m. The “small dinocysts undiff.” are present throughout the whole succession but are more abundant in the upper part of the succession (Fig. 5).

Figure 9Photos of selected taxa from the 2/11-12S well (offshore Norway). The scale bar of 20 µm applies to all photos. (a) Cannosphaeropsis passio, (b) Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum, (c) Cordosphaeridium cantharellus, (d) Exochosphaeridium insigne, (e) Impletosphaeridium insolitum, (f) small dinocyst undiff., (g) Impagidinium paradoxum, (h) Nematosphaeropsis lemniscata, (i) Melitasphaeridium choanophorum, (j) Palaeocystodinium miocaenicum/minor, (k) Spiniferites spp., (l) Unipontidinium aquaeductus.

The stratigraphically diagnostic dinocyst events, as recognized in Sheldon et al. (2025), include the LO of Cordosphaeridium cantharellus at 1659.69 m, the FO of Exochosphaeridium insigne at 1667.70 m and LO at 1633.61 m, the FO of Cousteaudinium aubryae at 1645.53 m and LO at 1551.29 m, the FO of Labyrinthodinium truncatum at 1606.14 m, and the FO of Unipontidinium aquaeductum at 1532.56 m and LO at 1498.34 m (Fig. 5).

In the 2/11-12S well, we identified only a few possibly reworked taxa: Gonyaulacysta jurassica (Upper Jurassic) at 1500.54 m, Deflandrea phosphoritica (Eocene to lowermost Miocene) at 1606.54 m, and Cordosphaeridium cantharellus (Eocene to Lower Miocene) at 1653.61 m (Supplement data file).

Only one inner neritic taxon is observed in our dataset (Homotryblium tenuispinosum). Few outer neritic and oceanic taxa (see Table 1) are present (e.g., Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum, Impagidinium spp., and Nematosphaeropsis spp.); Fig. 5.

Warm-water-tolerant species (Table 1), such as Lingulodinium machaerophorum, Impagidinium paradoxum, and Polysphaeridium zoharyi, were found throughout the succession. Polysphaeridium zoharyi only occurs from 1667.70 to 1561.39 m. The cool-water-tolerant taxon Filisphaera filifera was recorded from a single sample at 1654.72 m, while Habibacysta tectata is consistently present from 1525.80 m upwards (Fig. 5).

4.2.2 Palynofacies and index

The palynofacies data showed an overall trend with increasing dinocyst abundances and decreasing non-saccate pollen upwards (Fig. 6). Throughout the succession, the dinocyst abundance ranges between 44 % and 98 %. The non-saccate pollen varies between < 1 % and 23 %. The lower part of the succession (1671.22 to 1570.90 m) is characterized by the highest relative abundance of non-saccate pollen (between 5 % to 23 %). In the upper part of the studied succession (1570.90 to 1486.78 m), non-saccate pollen is present but less common (< 1 %–10 %).

Bisaccate pollen palynomorphs are present throughout the entire succession and vary from < 1 % to 23 %, showing a pattern similar to the non-saccate pollen, with the highest relative abundances in the lower part of the succession (1671.22 to 1570.90 m). Spores occur in most samples, especially in the lower part of the succession, but in very low numbers (< 1 %). Fungal spores are absent in all samples from the succession. Freshwater algae were only recorded in four samples and in very low numbers. Acritarchs are present in almost every sample, with a relative abundance between < 1% and 9 % (Fig. 6).

The index is the highest (between 29 % and 33 %) in the lower part of the succession (1671.22 to 1570.90 m); Fig. 7. In the upper part of the succession, from 1570.90 to 1486.78 m, the index is of a much lower value and ranges between 0 % and 12 %.

4.2.3 Biomarkers and palaeothermometry

None of the analysed neutral fractions yielded alkenones. In six out of seven samples, GDGTs were above the detection limit. GDGTs were too low in a sediment sample collected from 1672.0 m; therefore, the sample is not considered further here. The isoGDGT distributions in the remaining samples were assessed for non-thermal overprints, such as terrestrial input or contributions from methanogenic, methanotrophic, or deep-dwelling archaea, using indices established in the literature (e.g., Blaga et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011; Sinninghe Damsté et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2013; O'Brien et al., 2017). Overall, the BIT index (Hopmans et al., 2004) is less than 0.1 (Fig. 5). None of the samples show indications of non-thermal overprints. As such, the raw values, which vary between −0.50 and −0.23, are translated to temperatures varying between 14.5 and 23 °C (Fig. 5).

The highest temperatures occur in three samples from the mid-Burdigalian to the lowermost Langhian (the interval assigned from the E. insigne zone, the C. cantharellus zone, and the lower part of the L. truncatum zone). In the lower Burdigalian, SST was at least 3 °C colder. In the uppermost Langhian and Serravallian, the SST was 5–6 °C lower than during the warmest part of the record (Fig. 5). Notably, with the current dataset, we have no data from the middle part of the Langhian.

5.1 Dinocysts events

Both wells yield well-preserved dinocyst assemblages. Despite differences in the relative abundance and composition of the assemblages (see Sect. 5.2 for details), all key dinocyst events for the Burdigalian–Langhian succession were identified in both wells. Based on these events, the studied succession in the 2/11-12S well is subdivided by Sheldon et al. (2025) into the dinocyst zones S. hamulatum, C. cantharellus, E. insigne, C. aubryae, L. truncatum, and U. aquaeductum as defined by Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010). The LOs and FOs of stratigraphically important taxa identified in the Sdr. Vium well support the established zonal subdivision of the Miocene succession (Dybkjær and Piasecki, 2010; Śliwińska et al., 2024). An exception is the E. insigne zone, which is interpreted here as either missing or very condensed in this well (Fig. 3). This feature is likely due to an erosive surface observed at approximately 111 m, which marks the base of the prograding Odderup Formation.

A correlation of the two Miocene successions based on the dinocyst zonation (Fig. 7) clearly illustrates the significant difference in the sedimentation rates, as reflected by the thickness variation in the dinocyst zones between the two successions. The C. cantharellus zone in the Sdr. Vium well comprises approx. 32 m, while the same zone in the 2/11-12S well comprises approx. 8 m. The C. aubryae zone is nearly of the same thickness in both wells (i.e., 48 m in Sdr. Vium and at least 38 m in 2/11-12S). On the contrary, the L. truncatum zone and the U. aquaeductum zone are more condensed in the Sdr. Vium well (minimum 9 and 2 m, respectively) than in the 2/11-12S well (minimum 75 and 34 m, respectively). These thickness variations are controlled by accommodation space and sedimentation rate. In the area represented by the Sdr. Vium well, a maximum of approximately 50 m of accommodation space existed during the deposition of the studied succession, whereas, in the area represented by the 2/11-12S well, accommodation space was probably up to 600 m. The distinct increase in thickness in the 2/11-12S well compared to the Sdr. Vium well for the interval assigned to the Nora Formation (the L. truncatum zone and the lower part of the U. aquaeductum zone) is most likely due to the blooming of algae (diatoms) during this time interval.

5.2 Proximity to land

The palynological assemblages of the two investigated wells are markedly different, reflecting their varying proximities to the land area. Nearly all samples in the Sdr. Vium well are dominated by non-saccate pollen (19 % to 52 %), with dinocysts as the second most common group (7 % to 54 %) (Fig. 4). Spores and fungal spores make up < 1% to 4 % of the assemblages. Freshwater algae are present in the lowermost samples and make up < 1 % to 3 %. The index of 31 % to 88 % suggests a high terrestrial input and proximity to the land (Fig. 7). On the contrary, the palynological assemblages in the 2/11-12S well (Fig. 6) are dominated by dinocysts (44 % to 98 %), and non-saccate pollen are significantly less common (0 % to 23 %). The index is usually below ∼ 12 %, except for the lower part of the well, where it reaches 31 % (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, the values are significantly lower than in the Sdr. Vium well, reflecting a much more distal marine setting. Notably, the relative abundance of acritarchs (< 1 % to 9 %) is similar in both wells.

In the 2/11-12S well, spores make less than 1 % of the total palynomorphs (Fig. 6). Fungal spores, in contrast to the Sdr. Vium site, are absent (Fig. 4). A lack of fungal spores can be explained by the distal location of the 2/11-12S, since they are associated with terrestrial and nearshore marine environments (Ingold, 1971; Rees, 1980; Tyson, 1995). However, it is important to note that fungal spores may also be abundant in turbiditic settings, where they can be transported from degraded vegetation debris accumulated in coastal plains (Vieira and Jolley, 2020; Jolley et al., 2022). Therefore, the absence of fungal remains in this case supports a distal marine environment, with no direct input from nearshore sources. Freshwater algae appear very sporadically in the 2/11-12S well (< 1 %). Since freshwater algae do not tolerate brackish or saline waters, they indicate freshwater influx into the marine environment (Tyson, 1995). A distal marine setting with negligible content of soil organic matter in the 2/11-12S well is further confirmed by very low values (i.e., below 0.1) of the BIT index (Fig. 5), indicating a primary marine source of organic matter.

The composition of the dinocyst assemblages of the two studied wells reflects the proximal–distal sedimentary setting. The dinocyst assemblage is more diverse in the Sdr. Vium well than in the 2/11-12S well. Impagidinium spp. and Nematosphaeropsis (N. lemniscata and N. labyrinthus) are typical outer neritic/oceanic taxa (see Dale, 1996; Pross and Brinkhuis, 2005; Vieira and Jolley, 2020) and are observed in nearly all samples in the 2/11-12S well (Fig. 5). At some depths, N. lemniscata makes up to 3 %–5 % of the relative dinocyst assemblage. Except for a couple of isolated occurrences, Impagidinium spp. and Nematosphaeropsis spp. are nearly absent in the Sdr. Vium well (Fig. 3). Conversely, species associated with inner neritic nearshore settings are more common in the Sdr. Vium well. Homotryblium tenuispinosum is an extinct taxon associated with restricted marine to open marine inner neritic settings (Dybkjær, 2004b, and references therein) and is present in the Sdr. Vium well in low abundances (e.g., below 3 %; Fig. 3). In the 2/11-12S well, a single occurrence of the taxon was found in one sample only (Fig. 5). Polysphaeridium zoharyi, which today is observed in coastal sub-tropical to equatorial regions (Zonnenveld et al., 2013), is present in both wells but is more abundant in Sdr. Vium (up to 29 %). Notably, this taxon disappeared in both wells in the upper Langhian (Figs. 3 and 5). This may be related to the establishment of lower SST (see Sect. 5.4) following the global cooling trend after the MCO rather than changes in depositional settings. Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum is also present in both wells but is moderately more common in Sdr. Vium. Other common taxa, such as Spiniferites spp., Operculodinium centrocarpum, Dapsilidinium pseudocolligerum, and Lingulodinium machaerophorum, are equally common in both wells (Figs. 3 and 5).

5.3 Environmental changes

5.3.1 The Sdr. Vium well

The palynomorph assemblages from the Sdr. Vium well indicate that the lower part of the Arnum Formation (133.32–112.67 m; the C. cantharellus zone) received larger contributions of terrestrial material during deposition of the upper part of the formation (95.42–53.42 m; the C. aubryae zone) compared to the lower part (i.e., 133–110 m), as suggested by a slightly higher concentration of non-saccate pollen and the presence of freshwater algae (Fig. 4). A change from a less terrestrial-influenced ( index minimum of 27 % at 133.32 m) to a more terrestrial-influenced environment ( index maximum of 88 % at 53.42 m) is observed, but the sampling resolution is too low to reveal environmental changes in higher detail during the deposition of the Arnum Formation (Fig. 7). Overall, the depositional setting during the late Burdigalian and Langhian was characterized by the highest flux in terrestrial organic matter observed in our study. This agrees with the study by Rasmussen et al. (2010) (see also Śliwińska et al., 2024, for more details), where the area of the Sdr. Vium well during that time was considered to be predominantly shallow marine, with water depth varying between 0 and 50 m. These water depth estimates were based on a combination of fossils (molluscs and foraminifera) and a mapping of the clinoform break point observed in seismic profiles (for details, see Śliwińska et al., 2024).

5.3.2 The 2/11-12S well

Our data show that the Dany Formation (1671.22 to 1602.0 m) was deposited with a larger terrestrial input than the overlying formations. This is suggested by the highest content of non-saccate pollen, a nearly consistent record of spores (Fig. 6), and the highest values of the index (up to 33; Fig. 7). During the late Burdigalian (C. cantharellus zone to the C. aubryae zone), areas of both sites experienced the largest terrestrial influence as shown by e.g., higher index values (Fig. 5) and the highest concentration of non-saccate pollen (Figs. 4 and 6). This period coincides with an interval of increased sediment input from the Southern Scandes in the direction of the North Sea (via delta systems), resulting in a prograding coastline (see Rasmussen et al., 2010).

The overlying Nora (1602.0 to 1510.0 m) and Hodde (1510.0 to 1501.0 m) formations are characterized by a moderately smaller influx of terrestrial particles (Fig. 6) and a lower index (Fig. 7). The uppermost part of the Hodde Formation (at 1502.08 m) and the Ørnhøj Formation (1501.0 to 1480.0 m) yield nearly exclusively dinocysts (Fig. 6). Our current dataset does not provide the palynofacies data from the Hodde Formation in the Sdr. Vium well, but the overall more marine setting observed in the Ørnhøj Formation in the Sdr. Vium well corresponds with the most marine conditions observed in the 2/11-12S well during the deposition of these two formations.

5.4 Temperature trends

Both warm- and cool-water-tolerant dinocyst taxa were observed in both wells (Figs. 3 and 5). The warm-water-tolerant species, such as Lingulodinium machaerophorum, are distributed throughout the successions, with some small fluctuations in the abundance but with no apparent trend in time. However, under modern, colder-climate conditions than during the Miocene, L. machaerophorum can be found as far north as subpolar zones, north of Iceland (Zonneveld et al., 2013). This would suggest that L. machaerophorum may not be a good indicator of warm-water conditions in the coolhouse Miocene climate in the North Sea region. Today, Tectatodinium pellitum has a geographic distribution restricted to coastal sites from sub-tropical to equatorial regions (Zonneveld et al., 2013). In the North Sea, the taxon has been reported from the Eocene (Köthe and Piesker, 2007; Heilmann-Clausen and Van Simaeys, 2005). In our study, we observe the taxon in many samples, although it rarely accounts for more than 1 % of the relative dinocyst abundance (Figs. 3 and 5). We observe no apparent abundance trend in the succession. Therefore, we surmise that the taxon is not a useful indicator of changing surface water temperature in the studied region.

In contrast to the taxa mentioned thus far, Polysphaeridium zoharyi makes an interesting appearance pattern. In modern settings, P. zoharyi occurs primarily in coastal, fully marine subtropical to tropical regions, which may have a high productivity (Zonnenveld et al., 2013). The species is common in the Mediterranean Sea and does not reach farther north than southern Spain (Zonnenveld et al., 2013). In the North Sea, the taxon has been observed in low numbers in a couple of discrete samples scattered throughout the Eocene (Heilmann-Clausen and Van Simaeys, 2005; Köthe and Piesker, 2007) and the Oligocene (Schiøler, 2005; Van Simaeys et al., 2005; Köthe and Piesker, 2007). There is one exception in the Upper Oligocene onshore Denmark, where P. zoharyi and P. subtile reach an acme of 57 % of the dinocyst assemblage (the Horn-1 well; Śliwińska et al., 2012). In this case, the timing of the acme may possibly reflect warmer surface water conditions of the Late Oligocene Warming Event (e.g., O'Brien et al., 2020) recognized in the southern North Sea by De Man and Van Simaeys (2004). However, in the Miocene, the taxon has hitherto been recorded in rather low numbers (e.g., Schiøler, 2005). As shown in our study, in the proximal Miocene succession (Sdr. Vium), P. zoharyi makes two maxima of 23 % and 29 % of the relative dinocyst abundance (Fig. 3). Otherwise, the taxon is observed in nearly every sample (1 %–16 %) in the interval from the C. aubryae zone (depth 110.73 m) to the L. truncatum zone (the highest occurrence at 50.50 m). It is also present (up to 5 %) but less frequent in the lower part of the studied succession. In the distal setting (2/11-12S), P. zoharyi is less common (up to 5 %) but appears regularly from the middle part of the C. cantharellus zone (1616.86 m) to the middle part of the L. truncatum zone (1579.11 m). The taxon appears less regularly in the lower part of the record and makes a single occurrence in the Serravallian (Fig. 5). Among all the warm-water-tolerant taxa that exist today, P. zoharyi makes the most distinctive appearance in the late Burdigalian to early Langhian in the Sdr. Vium well, in an interval corresponding to the warmest part of the Miocene, e.g., the MCO.

In the Sdr. Vium well, the multiproxy temperature record shows a mismatch between the terrestrial and marine realm at the onset of the MCO (Śliwińska et al., 2024). However, the warmest part of the Miocene falls collectively in the interval corresponding with the deposition of the Aarnum Formation, itself corresponding with the C. aubryae and lower part of L. truncatum zones (Śliwińska et al., 2024). Our TEX86-derived SST record from the 2/11-12S wells suggests the warmest temperature of the Miocene in the E. insigne and C. aubryae zones and in the lowermost part of L. truncatum zones (Fig. 5). Even though the current dataset has a large gap in the middle part of the Langhian, the TEX86-derived temperature agrees overall with higher SSTs corresponding roughly with the MCO. Furthermore, in the 2/11-12S well, M. choanophorum, which is a species affiliated with the warm surface water (e.g., De Schepper, 2006), is most common in the interval assigned to the E. insigne and C. aubryae zones and (the lowermost part of) the L. truncatum zone (Fig. 5). However, in the proximal setting recorded in the Sdr. Vium well, the taxon is present in nearly every sample, with no apparent trend (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the LO of M. choanophorum with the concurrent appearance of cold-water-tolerant dinocysts has been observed offshore Scandinavia (Dybkjær et al., 2020).

The cool-water-tolerant species typical of the Upper Miocene succession (e.g., Quaijtaal et al., 2014) observed in our dataset includes Habibacysta tectata and Filisphaera filifera. However, F. filifera occurs only in one sample in the 2/11-12S well, in the C. cantharellus zone at 1654.72 m (Fig. 5), and is absent in the Sdr. Vium well (Fig. 3). Therefore, this taxon is not useful for tracing colder surface water conditions in our record. Dinocysts are marine plankton whose distribution and abundance are influenced by multiple environmental factors beyond temperature, such as light availability, salinity, sea surface temperature, and nutrient supply. It is therefore possible that these factors had a greater impact on the distribution of temperature-sensitive taxa, such as F. filifera in this case, than temperature itself.

On the contrary, H. tectata is present in both wells in the interval covering the upper Langhian and Serravallian, e.g., from the lower part of the U. aquaeductum zone (1525.80 m) to the top of the analysed interval (Figs. 3 and 5). The taxon is known from several northern high latitudes from the upper Langhian to the Tortonian (e.g., Piasecki, 2003; Schreck et al., 2012) or even to the Pleistocene (Matthiessen and Brenner, 1996). The appearance of the taxon in the North Sea in the latest Langhian and Serravallian is interpreted as an indicator of surface water cooling, related to the MCT. The taxon has been observed in time-equivalent deposits of the Nordic Sea (Schreck et al., 2017). The FO of H. tectata seems to be relatively synchronous in the northern mid- to high latitudes and can be considered a useful biostratigraphic event for the upper Langhian. However, the synchroneity of the event in the region would need to be investigated in more detail, e.g., by integrating dinocyst stratigraphy with magnetostratigraphy. Nevertheless, a lower surface water temperature corresponding with the presence of H. tectata is indicated by our TEX86 data in the 2/11-12S (Fig. 5) and by the alkenone-derived SST from the Sdr. Vium well (Herbert et al. 2020). Notably, the LO of P. zoharyi in both wells coincides with the first occurrence of H. tectata (Figs. 3 and 5). This suggests that the surface water in the late Langhian became too cold for P. zoharyi to thrive in the North Sea Basin. The LO of P. zoharyi in the eastern North Atlantic is observed later, around 13.1 Ma (Quaijtaal et al., 2014), suggesting that the taxon migrated south, towards warmer environments, as a consequence of the global cooling following the MCO.

-

Dinocyst biostratigraphy confirms the presence of key Burdigalian–Langhian dinocyst zones in both wells. We also observe thickness variations between zones reflecting differences in sedimentation rates or accommodation space, or both.

-

Palynofacies and dinocyst assemblages, as well as the index, show that the Sdr. Vium well was deposited in a nearshore setting with strong terrestrial influence, while the 2/11-12S well represents a more distal marine environment with minimal terrestrial input. The dinocyst assemblages reflect a clear proximal–distal gradient, with higher diversity and a greater abundance of neritic taxa (e.g., Homotryblium tenuispinosum, Polysphaeridium zoharyi) in the Sdr. Vium well and with lower diversity and an abundance of outer neritic/oceanic taxa (e.g., Impagidinium spp., Nematosphaeropsis spp.) in the more distal 2/11-12S well. The absence of fungal spores, along with the low BIT index, further supports a distal marine setting penetrated by the 2/11-12S well.

-

Among the warm-water taxa, P. zoharyi shows the most distinct stratigraphic pattern. Regardless of the proximity to the land, the taxon is present during the MCO. In the more proximal Sdr. Vium well, the taxon shows abundance peaks, while, in the more distal 2/11-12S well, the taxon is less abundant but consistently present. Our observations support using P. zoharyi as a regional indicator of elevated SSTs.

-

The first appearance of Habibacysta tectata and the concurrent disappearance of P. zoharyi in both wells during the late Langhian mark the onset of surface water cooling associated with the MCT, consistent with independent TEX86 and alkenone-derived SST records from the area.

All data are available in the main text or in the Supplement (https://doi.org/10.22008/FK2/F2YYEV, Kellner et al., 2025).

The samples are stored at GEUS, Oester Voldgade 10, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark. They can be accessed by contacting kksl@geus.dk.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-44-509-2025-supplement.

LFK and KKS wrote the paper with help from all co-authors. KD counted dinocysts and palynofacies in the 2/11-12S well. SP, KD, JMF, and LFK counted dinocysts from the Sdr. Vium well. LFK carried out the palynofacies analysis of the Sdr. Vium well. KKS, with help from MV and KD, created Figs. 3–7 using StrataBugs software.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Part of this research was carried out as a Master's thesis project by LFK, under the supervision of Lígia Castro and Manuel Vieira at NOVA School of Science and Technology in the Department of Earth Sciences. We thank the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) and Aker BP for providing sediment samples. We would like to thank Annette Ryge (GEUS) for preparing palynological slides. We would also like to thank Catherine Jex for providing valuable suggestions to improve the English language.

This research received support from the research centre GeoBioTec – NOVA-FCT pole (UIDB/04035/2020; https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04035/2020, GeoBioTec, 2020). Kasia K. Śliwińska acknowledges funding from Geocenter Denmark (grant no. 2-2024).

This paper was edited by Francesca Sangiorgi and reviewed by Alina I. Iakovleva and two anonymous referees.

Anthonissen, E. D.: A new Miocene biostratigraphy for the northeastern North Atlantic: an integrated foraminiferal, bolboformid, dinoflagellate and diatom zonation, Newsletters on Stratigraphy, 45, 281–307, https://doi.org/10.1127/0078-0421/2012/0025, 2012.

Bijl, P. K., Sliwinska, K. K., Duncan, B., Huguet, A., Naeher, S., Rattanasriampaipong, R., Sosa-Montes de Oca, C., Auderset, A., Berke, M., Kim, B. S., Davtian, N., Dunkley Jones, T., Eefting, D., Elling, F., O'Connor, L., Pancost, R. D., Peterse, F., Fenies, P., Rice, A., Sluijs, A., Varma, D., Xiao, W., and Zhang, Y.: Reviews and syntheses: Best practices for the application of marine GDGTs as proxy for paleotemperatures: sampling, processing, analyses, interpretation, and archiving protocols, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-1467, 2025.

Blaga, C. I., Reichart, G.-J., Heiri, O., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: Tetraether membrane lipid distributions in water-column particulate matter and sediments: a study of 47 European lakes along a north–south transect, Journal of Paleolimnology, 41, 523–540, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-008-9242-2, 2009.

Boyd, J. L., Riding, J. B., Pound, M. J., De Schepper, S., Ivanovic, R. F., Haywood, A. M., and Wood, S. E. L.: The relationship between Neogene dinoflagellate cysts and global climate dynamics, Earth-Science Reviews, 177, 366–385, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.11.018, 2018.

Clausen, O. R., Gregersen, U., Michelsen, O., and Sørensen, J. C.: Factors controlling the Cenozoic sequence development in the eastern parts of the North Sea, Journal of the Geological Society, 156, 809–816, https://doi.org/10.1144/gsjgs.156.4.0809, 1999.

Dale, B.: Dinoflagellate cyst ecology: modeling and geological applications, in: Palynology: principles and applications, edited by: Jansonius, J. and McGregor, D., American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists Foundation Dallas, TX, 1249–1275, ISBN 9780931871030, 1996.

De Man, E. and Van Simaeys, S.: Late Oligocene warming event in the southern North Sea Basin: Benthic foraminifera as paleotemperature proxies, Geologie en Mijnbouw/Netherlands Journal of Geosciences, 83, 227–239, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600020291, 2004.

De Schepper, S.: Plio‐Pleistocene dinoflagellate cyst biostratigraphy and palaeoecology of the eastern North Atlantic and southern North Sea Basin, PhD Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2006.

De Schepper, S., Head, M. J., and Louwye, S.: Pliocene dinoflagellate cyst stratigraphy, palaeoecology and sequence stratigraphy of the Tunnel-Canal Dock, Belgium, Geological Magazine, 146, 92–112, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756808005438, 2009.

De Schepper, S., Fischer, E. I., Groeneveld, J., Head, M. J., and Matthiessen, J.: Deciphering the palaeoecology of Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene dinoflagellate cysts, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 309, 17–32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.04.020, 2011.

De Vernal, A.: Marine palynology and its use for studying nearshore environments, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 5, 012002, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1307/5/1/012002, 2009.

Donders, T. H., Weijers, J. W. H., Munsterman, D. K., Kloosterboer-van Hoeve, M. L., Buckles, L. K., Pancost, R. D., Schouten, S., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Brinkhuis, H.: Strong climate coupling of terrestrial and marine environments in the Miocene of northwest Europe, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 281, 215–225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.02.034, 2009.

Dybkjær, K.: Dinocyst stratigraphy and palynofacies studies used for refining a sequence stratigraphic model – Uppermost Oligocene to lower Miocene, Jylland, Denmark, Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 131, 201–249, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2004.03.006, 2004a.

Dybkjær, K.: Morphological and abundance variations in Homotryblium-cyst assemblages related to depositional environments; uppermost Oligocene-Lower Miocene, Jylland, Denmark, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 206, 41–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2003.12.021, 2004b.

Dybkjær, K. and Piasecki, S.: Neogene dinocyst zonation for the eastern North Sea Basin, Denmark, Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 161, 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2010.02.005, 2010.

Dybkjær, K., Rasmussen, E. S., Śliwińska, K. K., Esbensen, K. H., and Mathiesen, A.: A palynofacies study of past fluvio-deltaic and shelf environments, the Oligocene-Miocene succession, North Sea Basin: A reference data set for similar Cenozoic systems, Marine and Petroleum Geology, 100, 111–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.08.012, 2019.

Dybkjær, K., Rasmussen, E. S., Eidvin, T., Grøsfjeld, K., Riis, F., Piasecki, S., and Śliwińska, K. K.: A new stratigraphic framework for the Miocene – Lower Pliocene deposits offshore Scandinavia: A multiscale approach, Geological Journal, 56, 1699–1725, https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.3982, 2020.

Eidvin, T. and Rundberg, Y.: Late Cainozoic stratigraphy of the Tampen area (Snorre and Visund fields) in the northern North Sea, with emphasis on the chronology of early Neogene sands, Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, 81, 119–160, 2001.

Eidvin, T. and Rundberg, Y.: Post-Eocene strata of the southern Viking Graben, northern North Sea; integrated biostratigraphic, strontium isotopic and lithostratigraphic study, Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, 87, 391–450, 2007.

Eidvin, T., Ullmann, C. V., Dybkjær, K., Rasmussen, E. S., and Piasecki, S.: Discrepancy between Sr isotope and biostratigraphic datings of the upper middle and upper Miocene successions (Eastern North Sea Basin, Denmark), Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 411, 267–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.07.005, 2014.

GeoBioTec: Department of Earth and Sciences, NOVA University – FCT, Lisbon, Research Center funding reference UIDB/04035/2020, https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04035/2020, 2020.

Gregersen, U.: Upper Cenozoic channels and fans on 3D seismic data in the northern Norwegian North Sea, Petroleum Geoscience, 4, 67–80, https://doi.org/10.1144/petgeo.4.1.67, 1998.

Head, M. J.: Morphology and Paleoenvironmental significance of the Cenozoic dinoflagellate genera Tectatodinium and Habibacysta, Micropaleontology, 40, 289–321, https://doi.org/10.2307/1485937, 1994.

Head, M. J.: Modern dinoflagellate cysts and their biological affnities, in: Palynology: principles and applications, edited by: Jansonius, J. and McGregor D.C., 1197–1248, ISBN 9-931871-03-4, 1996.

Head, M. J.: Thermophilic dinoflagellate assemblages from the mid Pliocene of eastern England, Journal of Paleontology, 71, 165–193, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022336000039123, 1997.

Heilmann-Clausen, C. and Van Simaeys, S.: Dinoflagellate cysts from the Middle Eocene to lowermost Oligocene succession in the Kysing research borehole, Central Danish Basin, Palynology, 29, 143–204, https://doi.org/10.2113/29.1.143, 2005.

Herbert, T. D., Lawrence, K. T., Tzanova, A., Peterson, L. C., Caballero-Gill, R., and Kelly, C. S.: Late Miocene global cooling and the rise of modern ecosystems, Nature Geoscience, 9, 843–847, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2813, 2016.

Herbert, T. D., Rose, R., Dybkjær, K., Rasmussen, E. S., and Śliwińska, K. K.: Bi-Hemispheric Warming in the Miocene Climatic Optimum as Seen from the Danish North Sea, Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, e2020PA003935, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020PA003935, 2020.

Hopmans, E. C., Schouten, S., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S.: The effect of improved chromatography on GDGT-based palaeoproxies, Organic Geochemistry, 93, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2015.12.006, 2016.

Hopmans, E. C., Weijers, J. W. H., Schefuß, E., Herfort, L., Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., and Schouten, S.: A novel proxy for terrestrial organic matter in sediments based on branched and isoprenoid tetraether lipids, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 224, 107–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2004.05.012, 2004.

Howarth, R. J. and McArthur, J. M.: Statistics for Strontium Isotope Stratigraphy: A Robust LOWESS Fit to the Marine Sr-Isotope Curve for 0 to 206 Ma, with Look-up Table for Derivation of Numeric Age, The Journal of Geology, 105, 441–456, https://doi.org/10.1086/515938, 1997.

Hönisch, B., Royer, D. L., Breecker, D. O., Polissar, P. J., Bowen, G. J., Henehan, M. J., Cui, Y., Steinthorsdottir, M., McElwain, J. C., Kohn, M. J., Pearson, A., Phelps, S. R., Uno, K. T., Ridgwell, A., Anagnostou, E., Austermann, J., Badger, M. P. S., Barclay, R. S., Bijl, P. K., Chalk, T. B., Scotese, C. R., de la Vega, E., DeConto, R. M., Dyez, K. A., Ferrini, V., Franks, P. J., Giulivi, C. F., Gutjahr, M., Harper, D. T., Haynes, L. L., Huber, M., Snell, K. E., Keisling, B. A., Konrad, W., Lowenstein, T. K., Malinverno, A., Guillermic, M., Mejía, L. M., Milligan, J. N., Morton, J. J., Nordt, L., Whiteford, R., Roth-Nebelsick, A., Rugenstein, J. K. C., Schaller, M. F., Sheldon, N. D., Sosdian, S., Wilkes, E. B., Witkowski, C. R., Zhang, Y. G., Anderson, L., Beerling, D. J., Bolton, C., Cerling, T. E., Cotton, J. M., Da, J., Ekart, D. D., Foster, G. L., Greenwood, D. R., Hyland, E. G., Jagniecki, E. A., Jasper, J. P., Kowalczyk, J. B., Kunzmann, L., Kürschner, W. M., Lawrence, C. E., Lear, C. H., Martínez-Botí, M. A., Maxbauer, D. P., Montagna, P., Naafs, B. D. A., Rae, J. W. B., Raitzsch, M., Retallack, G. J., Ring, S. J., Seki, O., Sepúlveda, J., Sinha, A., Tesfamichael, T. F., Tripati, A., van der Burgh, J., Yu, J., Zachos, J. C., and Zhang, L.: Toward a Cenozoic history of atmospheric CO2, Science, 382, eadi5177, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi5177, 2023.

Ingold, C. T.: Fungal spores: their liberation and dispersal, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 302 pp., ISBN 978-0198541158, 1971.

Jolley, D., Vieira, M., Jin, S., and Kemp, D.: Palynofloras, paleoenvironmental change and the inception of the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum; the record of the Forties Fan, Sele Formation, North Sea Basin, J. Geol. Soc., jgs2021-131, https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2021-131, 2022.

Kellner, L., Dybkjær, K., Piasecki, P., Fredborg, J., Peterse, F., Rasmussen, E., Vieira, M., Castro, L., and Sliwinska, K.: Early to Middle Miocene in the North Sea Basin: proxy-based insights into environment, depositional settings and sea surface temperature evolution Supplementary Data, Dataverse GEUS [data set], https://doi.org/10.22008/FK2/F2YYEV, 2025.

Kim, J. H., van der Meer, J., Schouten, S., Helmke, P., Willmott, V., Sangiorgi, F., Koç, N., Hopmans, E. C., and Damsté, J. S. S.: New indices and calibrations derived from the distribution of crenarchaeal isoprenoid tetraether lipids: Implications for past sea surface temperature reconstructions, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 74, 4639–4654, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2010.05.027, 2010.

King, C., Gale, A. S., and Barry, T. L.: A revised correlation of Tertiary rocks in the British Isles and adjacent areas of NW Europe, Geological Society of London, https://doi.org/10.1144/sr27, 2016.

Knox, R. W. O. B., Bosh, J. H. A., Rasmussen, E. S. H.-C. C., Hiss, M., Kasiński, J., King, C., Köthe, A., Słodkowska, B., and Standke, G. V. N.: Cenozoic, in: Petroleum Geological Atlas of the Southern Permian Basin Area., edited by: Doornenbal, J. C., and Stevenson, A. G., EAGE Publication B.V., Houten, 211–223, ISBN 978-90-73781-83-2, 2010.

Köthe, A. and Piesker, B.: Stratigraphic distribution of Paleogene and Miocene dinocysts in Germany, Revue de Paleobiologie, 26, 1–39, 2007.

Larsson, L. M., Dybkjær, K., Rasmussen, E. S., Piasecki, S., Utescher, T., and Vajda, V.: Miocene climate evolution of northern Europe: A palynological investigation from Denmark, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 309, 161–175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.05.003, 2011.

Laursen, G. V. and Kristoffersen, F. N.: Detailes foraminiferal biostratigraphy of Miocene formations in Denmark, Contributions to Tertiary and Quaternary Geology, 36, 73–107, 1999.

Liboriussen, J., Ashton, P., and Tygesen, T.: The tectonic evolution of the Fennoscandian Border Zone in Denmark, Tectonophysics, 137, 21–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(87)90310-6, 1987.

Marret, F. and Zonneveld, K. A. F.: Atlas of modern organic-walled dinoflagellate cyst distribution, Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 125, 1–200, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-6667(02)00229-4, 2003.

Matthiessen, J. and Brenner, W. W.: Dinoflagellate cyst ecostratigraphy of Pliocene-Pleistocene sediments from the Yermak Plateau (Arctic Ocean, Hole 911A), in: Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 151, edited by: Thiede, J., Myhre, A. M., Firth, J. V., Johnson, G. L., and Ruddiman, W. F., https://doi.org/10.2973/odp.proc.sr.151.109.1996, 1996.

McCarthy, F., Gostlin, K., Mudie, P., and Hopkins, J.: Terresirial and marine palynomorphs as sea-level proxies: an example from Quaternary sediments on the New Jersey Margin, USA, 119–129, https://doi.org/10.2110/pec.03.75.0119, 2003.

McCarthy, F. M. G. and Mudie, P. J.: Oceanic pollen transport and pollen: dinocyst ratios as markers of late Cenozoic sea level change and sediment transport, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 138, 187–206, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(97)00135-1, 1998.

Michelsen, O., Danielsen, M., Heilmann-Clausen, C., Laursen, G., and Thomsen, E.: Occurrence of major sequence stratigraphic boundaries in relation to basin development in Cenozoic deposits of the southeastern North Sea, in: Sequence Stratigraphy on the Northwest European Margin, edited by: Steel, R. J. and Al, E., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 415–427, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-8937(06)80079-2, 1995.

Michelsen, O., Thomsen, E., Danielsen, M., Heilmann-Clausen, C., Jordt, H., and Laursen, G. V.: Cenozoic Sequence Stratigraphy in the Eastern North Sea, in: Mesozoic and Cenozoic Sequence Stratigraphy of European Basins, edited by: Graciansky, P.-C. D., Hardenbol, J., Jacquin, T., and Vail, P. R., SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology, https://doi.org/10.2110/pec.98.02.0091, 1999.

Miller, K. G., Wright, J. D., and Fairbanks, R. G.: Unlocking the Ice House: Oligocene-Miocene oxygen isotopes, eustasy, and margin erosion, Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 96, 6829–6848, https://doi.org/10.1029/90JB02015, 1991.

Mogensen, T. E. and Jensen, L. N.: Cretaceous subsidence and inversion along the Tornquist Zone from Kattegat to the Egersund Basin, First Break, 12, 211–222, 1994.

Mudie, P. J.: Pollen distribution in recent marine sediments, eastern Canada, Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 19, 729–747, https://doi.org/10.1139/e82-062, 1982.

Munsterman, D. K. and Brinkhuis, H.: A southern North Sea Miocene dinoflagellate cyst zonation, Geologie en Mijnbouw, 83, 267–285, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600020369, 2013.

O'Brien, C., Robinson, S., Pancost, R., Sinninghe-Damste, J., Schouten, S., Lunt, D., Alsenz, H., Bornemann, A., Bottini, C., Brassell, S., Farnsworth, A., Forster, A., Huber, B., Inglis, G., Jenkyns, H., Linnert, C., Littler, K., Markwick, P., McAnena, A., and Wrobel, N.: Cretaceous sea-surface temperature evolution: Constraints from TEX86 and planktonic foraminiferal oxygen isotopes, Earth-Science Reviews, 172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.07.012, 2017.

O'Brien, C. L., Huber, M., Thomas, E., Pagani, M., Super, J. R., Elder, L. E., and Hull, P. M.: The enigma of Oligocene climate and global surface temperature evolution, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117, 25302–25309, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2003914117, 2020.

Piasecki, S.: Neogene dinoflagellate cysts from Davis Strait, offshore West Greenland, Marine and Petroleum Geology, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8172(02)00089-2, 2003.

Powell, A. J.: Dinoflagellate cysts of the Tertiary System, in: A stratigraphic index of dinoflagellate cysts, edited by: Powell, A. J., BMS Occasional Publicaton Series, Chapman and Hall, London, 153–155, ISBN 0412362805, 1992.

Pross, J. and Brinkhuis, H.: Organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts as paleoenvironmental indicators in the Paleogene; a synopsis of concepts, Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 79, 53–59, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03021753, 2005.