the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Deep-sea benthic foraminiferal response to the Late Lutetian Thermal Maximum at Demerara Rise (ODP Site 1260, equatorial western Atlantic)

Irene Peñalver-Clavel

Thomas Westerhold

Laia Alegret

The Late Lutetian Thermal Maximum (LLTM) was a short-lived warming event recorded in the middle Eocene, at ∼ 41.52 Ma. It has been linked to the highest insolation values of the last 45 million years on Earth's surface. In order to understand the effects of the LLTM warming in deep-sea ecosystems, the benthic foraminiferal response to the LLTM is documented at Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Site 1260 in Demerara Rise, equatorial western Atlantic. Previous studies at this site reveal the LLTM is defined by a negative excursion in carbon and oxygen stable isotopes, minimal %CaCO3, elevated X-ray fluorescence (XRF) Fe, and a dark clay-rich layer, indicating CaCO3 dissolution. Our analyses reveal changes in the benthic foraminiferal assemblages and in the sediment components across the LLTM. Carbonate dissolution during the LLTM is supported by the decrease in planktic foraminifera, an increase in siliceous components and in the number of fish teeth, poor preservation of the benthic foraminiferal tests, and increased relative abundance of CaCO3 corrosion-resistant taxa (e.g. Nuttallides truempyi, Oridorsalis umbonatus). The lowest benthic foraminiferal accumulation rates and diversity of the assemblages during the peak LLTM warming may be indicative of lower export productivity and environmental stress; alternatively, they may result from a taphonomic bias due to CaCO3 dissolution. The comparison of these results with the available benthic foraminiferal studies in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans leads to the conclusion that the environmental response to the LLTM was strongly influenced by the palaeogeographic and palaeoceanographic setting.

- Article

(5189 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(530 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The gradual cooling trend from the warmhouse state of the middle to late Eocene towards the Eocene–Oligocene transition (Westerhold et al., 2020) was interrupted by short-lived warming events. These events, called hyperthermals (e.g. Thomas et al., 2000; Foster et al., 2018), are identified in deep-marine sediments by a paired negative excursion in the oxygen and carbon isotope composition of bulk sediment and benthic foraminifera (e.g. Wade and Kroon, 2002; Bohaty and Zachos, 2003; Westerhold et al., 2018). High pCO2 levels (e.g. Bijl et al., 2010; Pearson, 2010) and marine carbonate dissolution (e.g. Leon-Rodriguez and Dickens, 2010; Sexton et al., 2011) are typically associated with these events and point to perturbations of the global carbon cycle (e.g. Lyle et al., 2005; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020).

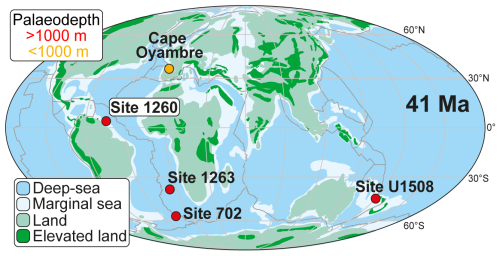

Other hyperthermal events, like the Late Lutetian Thermal Maximum (LLTM), have been associated with high insolation on Earth's surface (the highest of the last 45 million years), elevated pCO2 levels, and an accelerated hydrological cycle (Westerhold and Röhl, 2013; Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al., 2018; Westerhold et al., 2018). Studying the biotic response to intensified insolation, and the subsequent planetary warming, provides valuable insights into ecological dynamics during such extreme climate events. However, only a few studies are available across the LLTM, and most of them are focused on the Atlantic Ocean, with a unique site studied in the Pacific Ocean. In the equatorial and south Atlantic Ocean, the LLTM has been documented at Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Sites 702, 1260, and 1263 (Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold and Röhl, 2013; Westerhold et al., 2018; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020). In the northeast Atlantic, it has been reported from the Spanish Cape Oyambre section in the Basque–Cantabrian Basin (Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al., 2018). In the southwest Pacific, the LLTM has been documented at International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Site U1508 in the Tasman Sea (Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2024). All these studies record the negative excursion in carbon and oxygen stable isotopes and decreased CaCO3 content.

Deep-sea benthic foraminifera are a key tool to understand and reconstruct palaeoenvironmental conditions during the Paleogene (Alegret et al., 2021a; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2022), since they provide one of the best deep-sea fossil records during the Cenozoic. Multiple studies have explored their faunal turnover across early Eocene hyperthermal events (e.g. Jennions et al., 2015; Alegret et al., 2016, 2021b; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2018), and their response to the largest hyperthermal event of the Paleogene, the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), has been widely reported (e.g. Tjalsma and Lohmann, 1983; Thomas, 1998, 2007; Alegret et al., 2009, 2010, 2018; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2018). However, few works have considered the response of benthic foraminiferal assemblages to the hyperthermals of the middle Eocene (Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al., 2018; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2022), and the effects of the LLTM in particular have only been reported from the Atlantic Cape Oyambre section, situated on a continental marginal setting (middle bathyal depths, 600–1000 m; Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al., 2018); the Atlantic ODP Site 702 (lower bathyal depths, 1000–2000 m; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020); and the Pacific IODP Site U1508 (lower bathyal depths, 1000–2000 m; Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2024). The three studies show a marked decrease in diversity of the assemblages but no extinctions across the LLTM, along with temporary shifts in the abundance of benthic foraminiferal species.

This study documents the response of benthic foraminiferal assemblages to the LLTM at IODP Site 1260 in the equatorial western Atlantic, and it complements the previous publications of this hyperthermal event from Westerhold and Röhl (2013) and Westerhold et al. (2018). After evaluating the effects of the warming at this site by combining all the available data, the results are compared with the three other locations in the Atlantic Ocean where the LLTM has been documented and with the only study available in the Pacific Ocean. This integration allows a deeper understanding of how hyperthermal events related to orbital forcing affect marine ecosystems.

Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 207 drilled two holes (A and B) at Site 1260 (2549 m b.s.l., metres below sea level) on the gently dipping (∼ 1°) northwest-facing slope of Demerara Rise, a continental shelf off the coast of Surinam, equatorial western Atlantic (Fig. 1). Located on a ridge of Paleogene sediments subcropping near the seafloor (Erbacher et al., 2004), this site provided a remarkably complete and continuous middle Eocene sedimentary sequence, and it contains an abundant record of both siliceous and carbonate microfossils (Meunier and Danelian, 2022).

Figure 1Palaeogeographic map at 41 Ma, modified from Peñalver-Clavel et al. (2024), showing the location of sites where the LLTM has been studied, including their palaeobathymetry.

At Site 1260, early Eocene–Oligocene sediments are represented by pelagic nannofossil chalk with foraminifers (Unit II; Erbacher et al., 2004). The study interval (Subunit IIB; Erbacher et al., 2004) consists of light greenish-grey calcareous biogenic (50 % nannofossils) chalk containing common to abundant radiolarians (25 %–30 %). It is characterized by a high carbonate content (70 wt %). Within this subunit, planktic foraminifers are scarce at the top but increase in abundance deeper in Core 207-1260A-7R, and diatoms and siliceous sponge spicules are common. Bioturbation is moderate to pervasive, and subtle dark–light colour alternations (20–30 cm scale) with mottled contacts are observed (Erbacher et al., 2004).

The cyclic sedimentary succession at this site extends across magnetochrons C18r to C20r, from the late Lutetian into the early Bartonian, and is precisely constrained by its outstanding biostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic age control (Erbacher et al., 2004; Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold and Röhl, 2013).

Today, Site 1260 is situated at a latitude of 9° N, but it was much closer to the Equator (1° N) during the middle Eocene (Suganuma and Ogg, 2006; Renaudie et al., 2010).

3.1 Sampling strategy

The study material at Site 1260 includes samples from Holes A and B. At Hole 1260A, the study interval ranges from Core 9R, Section 6, interval 65–67 cm (74.46 revised metres composite depth, rmcd) to interval 138–140 (75.19 rmcd). At Hole 1260B, this interval ranges from Core 5R, Section 2, interval 4–6 cm (75.22 rmcd) to interval 135–137 (76.53 rmcd).

According to published studies of inorganic geochemistry, iron intensity records by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanning and cyclostratigraphy at ODP Site 1260 (Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold and Röhl, 2013; Westerhold et al., 2018), the LLTM ranges from 75.501–74.957 rmcd. This interval includes the highest insolation value of the last 45 Ma at 41.52 Ma, along with a negative CIE (0.86 ‰ in bulk sediment and 1.26 ‰ in planktic foraminifera) and OIE (1.8 ‰ in bulk sediment and 0.3 ‰ in planktic foraminifera), the lowest percentages of CaCO3, and the highest values of XRF Fe area (Fig. 2).

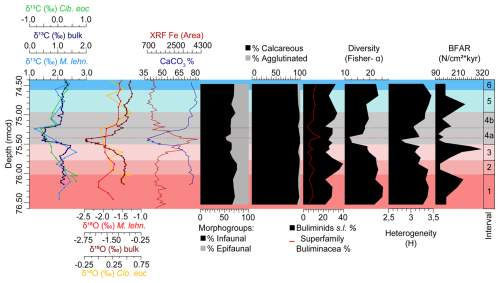

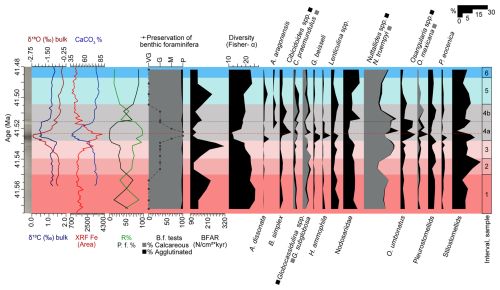

Figure 2Stable isotopes measured on bulk carbonate, planktic (Morozovelloides lehneri) and benthic foraminifera (Cibicidoides eocaenus) (Sexton et al., 2006; Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold et al., 2018); XRF core scanning Fe intensities (Westerhold and Röhl, 2013), coulometric CaCO3 content (Westerhold et al., 2018), and benthic foraminiferal indices (this study) at ODP Site 1260, plotted against depth (rmcd). The dashed black line marks the limit between subinterval 4a and 4b, and the red one corresponds to the depths of maximum dissolution.

XRF scanning data from Westerhold and Röhl (2013) and the high-resolution isotopic record from Westerhold et al. (2018) were used as a guideline to plan the sampling strategy for benthic foraminiferal studies across the short-lived LLTM. The age model of Westerhold and Röhl (2013) was updated (Table S1 in the Supplement) using the CENOGRID data from Westerhold et al. (2020) in order to compare the benthic foraminiferal response to the warming at Site 1260 with previous studies focused on benthic foraminiferal assemblages.

To precisely constrain the event, sampling was performed across two cores for a total interval of 2.07 m (from 74.46–76.53 rmcd), including the study of pre- and post-event intervals. This high-resolution sampling corresponds to an average resolution of 11.6 cm, with a spacing of 3–20 cm. The resulting temporal resolution averaged 4.73 kyr, ranging from 1.3–9.1 kyr, showing the finest resolution across the event.

3.2 Benthic foraminifera

Quantitative analyses of benthic foraminiferal assemblages were performed on 21 samples (Table S2). Sediment samples were oven-dried at 40 °C, weighed, and soaked in Na6(PO3)6 over 4 h. Disaggregated samples were then washed over a >63 µm size fraction, and the remaining residue was oven-dried and weighed. Benthic foraminifera are rare relative to total sediment particles in the >63 µm fraction of most studied samples. Additional sedimentary components include planktic foraminifera and calcareous nannofossils, as well as diatoms, radiolarians, sponge spicules, and fish teeth.

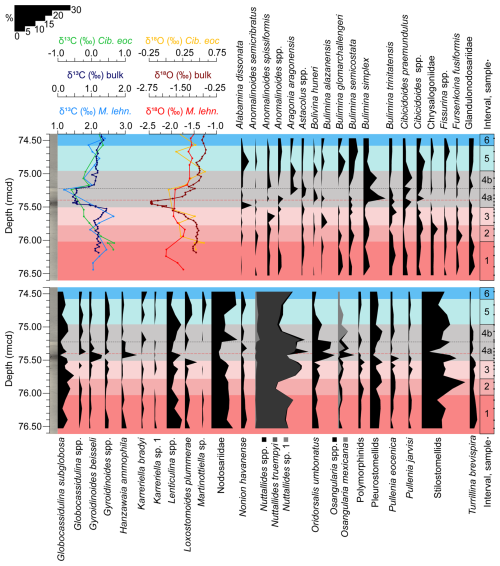

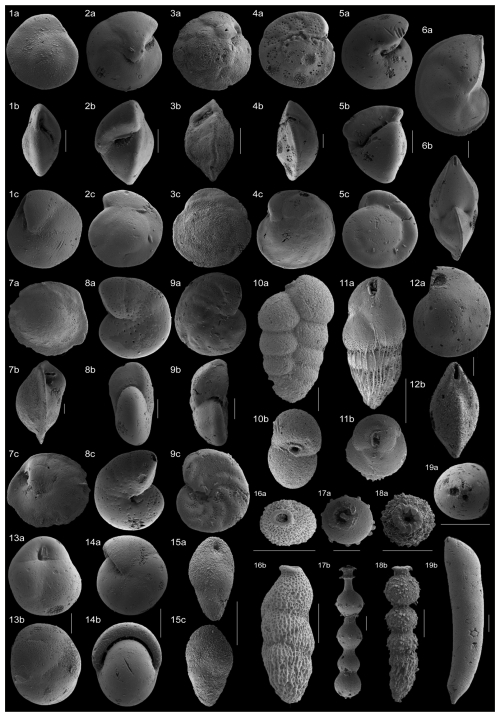

For the quantitative analysis of the assemblages, ca. 300 benthic foraminifera were picked per sample. The picked specimens were placed in micropalaeontological slides for a permanent record, which are housed in the collection of the Benthic Foraminifera and Global Change Lab of the Department of Earth Sciences at Zaragoza University, Spain. Taxonomic identification follows Van Morkhoven et al. (1986), Loeblich and Tappan (1987), Alegret and Thomas (2001), Kaminski and Gradstein (2005), Hayward et al. (2010), Holbourn et al. (2013), Moebius et al. (2014), and Arreguín-Rodríguez et al. (2018). Relative abundances of each taxon were calculated using the raw count matrix (Table S2). The relative abundances of taxa that make up more than 2 % of the assemblages in at least one sample are illustrated in Fig. 3, and the specimens of the most representative species (≥ 4 % of the assemblages) were photographed using the Scanning Electron Micrograph imaging facilities (JEOL JSM 6360-LV) at the Microscopy Service of the University of Zaragoza (Spain) (Fig. 4).

Figure 3Stable isotopes measured on bulk carbonate, planktic (Morozovelloides lehneri), and benthic foraminifera (Cibicidoides eocaenus) (Sexton et al., 2006; Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold et al., 2018) and relative abundance of benthic foraminiferal taxa that make up >2 % of the assemblages at ODP Site 1260, plotted against depth (rmcd). The dashed black line marks the limit between subinterval 4a and 4b, and the red one corresponds to the depths of maximum dissolution.

Figure 4SEM images of the benthic foraminiferal taxa that make up >4 % of the assemblages across the study interval. (1a–c) Alabamina dissonata, sample 1260A, 9R (6, 115–117 cm); (2a–c) Oridorsalis umbonatus, sample 1260B, 5R (2, 122–124 cm); (3a–c) Nuttallides truempyi, sample 1260A, 9R (6, 65–67 cm); (4a–c) Cibicidoides praemundulus, sample 1260B, 5R (2, 122–124 cm); (5a–c) Gyroidinoides beisseli, sample 1260B, 5R (2, 92–94 cm); (6a–b) Lenticulina sp., sample 1260B, 5R (2, 75–77 cm); (7a–c) Osangularia mexicana, 1260A, 9R (5, 125–127 cm); (8a–c) Anomalinoides spissiformis, sample 1260A, 9R (5, 125–127 cm); (9a–c) Hanzawaia ammophila, sample 1260B, 5R (2, 122–124 cm); (10a–b) Karreriella bradyi, sample 1260B, 5R (2, 122–124 cm); (11a–b) Bulimina semicostata, 1260A, 9R (6, 65–67 cm); (12a–b) Lenticulina sp., 1260B, 5R (2, 65–67 cm); (13a–b) Globocassidulina subglobosa, 1260B, 5R (2, 75–77 cm); (14a–b) Pullenia eocenica, 1260A, 9R (6, 125–127 cm); (15a–b) Bulimina simplex, 1260B, 5R (2, 65–67 cm); (16a–b) Loxostomoides plummerae, 1260A, 9R (5, 125–127 cm); (17a–b) stilostomellid, 1260A, 9R (6, 85–87 cm); (18a–b) stilostomellid, 1260B, 5R (2, 4–6 cm); (19a–b) Nodosariidae, 1260B, 5R (2, 122–124 cm). All scale bars = 100 µm.

The percentage of calcareous and agglutinated tests and two diversity indices were calculated (Fig. 2). The Shannon–Weaver heterogeneity index H(S) was calculated by considering the number of species (S) and their relative abundance (pi) in the sample, following Murray (1991) and applying the formula (pi. lnpi). The Fisher-α diversity index was calculated using http://groundvegetationdb-web.com/ground_veg/home/diversity_index (last access: 4 April 2025). The percentage of infaunal and epifaunal morphogroups (Corliss, 1991; Corliss and Chen, 1988; Jones and Charnock, 1985) was also calculated to infer trophic and oxygenation conditions in the benthic habitat (Fig. 2), with epifaunal-dominated assemblages typical of oligotrophic/well-oxygenated environments and with assemblages dominated by infaunal morphogroups generally indicating eutrophic conditions at the seafloor/oxygen deficiency of bottom waters (Jorissen et al., 2007). Nevertheless, interpreting fossil morphogroups requires prudence due to potential inconsistencies between morphology and habitat in living foraminifera (Buzas et al., 1993) and the lack of some modern analogues (Hayward et al., 2012). This issue is exacerbated when compositional changes at the species level within a morphogroup do not alter its total abundance (e.g. Alegret and Thomas, 2009; Alegret et al., 2021b).

The relative abundances of buliminids s.l. and the superfamily Buliminacea (Sen Gupta, 1999) were calculated (Fig. 2). A high food supply is often associated with their high abundance (Gooday, 2003; Jorissen et al., 1995, 2007), although these taxa also flourish in low-oxygen conditions (Jorissen et al., 1995; Thomas, 1990). The benthic foraminiferal accumulation rates (BFARs; Herguera and Berger, 1991), a proxy for total organic matter flux to the seafloor (Gooday, 2003; Herguera, 2000; Jorissen et al., 2007), were calculated multiplying the number of benthic foraminifera per gram of bulk sediment by the linear sedimentation rate (derived from the refined age model) and the dry bulk sediment (Erbacher et al., 2004) (Fig. 2).

Palaeobathymetric estimations based on benthic foraminifera rely on the comparison of modern and fossil assemblages, assessing the presence and abundance of depth-specific species and identifying their upper depth limits (e.g. Tjalsma and Lohmann, 1983; Van Morkhoven et al., 1986; Alegret and Thomas, 2001; Hayward et al., 2010). The bathymetric divisions by Van Morkhoven et al. (1986) were followed.

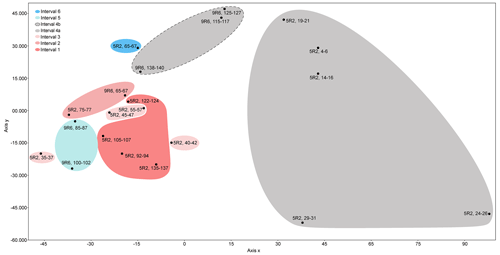

To statistically assess the assemblages, the PAST software (Hammer et al., 2001) was used to analyse a data matrix including all the studied samples and selected species that showed relative abundance >2 % in at least one sample. Hierarchical cluster analysis on samples (Q-mode) was processed using the correlation similarity index and the unweighted pair-group average algorithm (UPGMA) (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). To deepen the understanding of the clustering results, and to examine the correlation between foraminifera and environmental variables (Hammer and Harper, 2005; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020), a detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) was performed on samples (Q-mode) and species (R-mode) using the same dataset (Figs. 5 and S2, respectively).

Figure 5Detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) plot displaying the studied samples at ODP Site 1260.

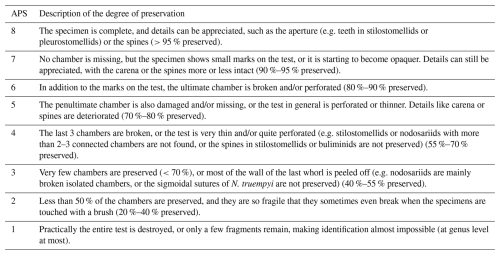

Additionally, a qualitative analysis of benthic foraminiferal test preservation was carried out across the study interval (Fig. 6). Following Boltovskoy and Totah (1992) and Nguyen et al. (2009), a scale to measure the preservation state of benthic foraminifera was employed. This assessment was applied to representative infaunal (Nodosariidae, Karreriella spp., stilostomellids, Bulimina spp., Oridorsalis umbonatus, Lenticulina spp., Globocassidulina subglobosa, and pleurostomellids) and epifaunal taxa (Osangularia spp., Nuttallides truempyi, Cibicidoides spp., Gyroidinoides spp., and Anomalinoides spp.) to evaluate whether both morphogroups were affected by carbonate corrosivity. A range of absolute preservation score (APS) on a scale from 8 to 1 was assigned to each identified taxon within a sample (Table 1; modified from Nguyen et al., 2009). Based on the observed APS ranges, the following preservation categories were established: very good (VG, APS ≥ 7), good (G, APS 6–8), moderate (M, APS 5–7), and poor (P, APS 2–6) (Table S4).

3.3 Other components of the sediment

To better understand environmental changes across the LLTM, semi-quantitative and quantitative analyses of other components of the sediment were carried out in the >63 µm size fraction for the above 21 sediment samples.

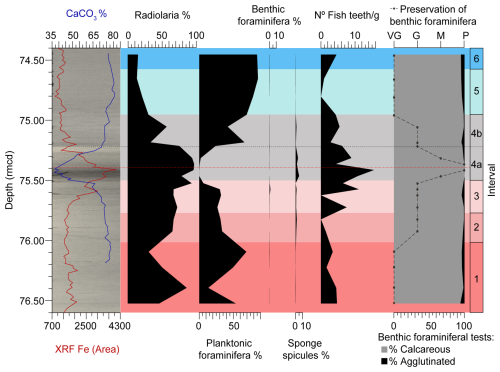

For semi-quantitative analyses, before picking the scarce benthic foraminifera, the samples were examined on a sampling tray, and the number of radiolarians, planktic and benthic foraminifera, and sponge spicules present in the 1 × 1 cm square of the tray were counted. The relative abundance of each group was calculated to obtain the percentage per sample (Table S3) (Fig. 6).

For quantitative analyses, we picked all fish teeth present in the sample aliquot from which 300 benthic foraminifera were retrieved. The number of fish teeth per gram of sediment was then calculated (Table S3) (Fig. 6).

4.1 Quantitative analyses of benthic foraminiferal assemblages

A total of 82 taxa (73 calcareous and 9 agglutinated) were recognized at the species taxonomic level or higher. Benthic foraminiferal assemblages are strongly dominated by calcareous taxa (≥ 93 % of the assemblages) across the study interval. Agglutinated foraminifera are a minor component (Fig. 2), and they mostly consist of infaunal biserial–triserial taxa such as Karreriella bradyi or Dorothia sp. (Fig. 3). Infaunal morphogroups dominate, making up 52.5 %–76.2 % of the assemblages (Fig. 2), and they are represented by common uniserial elongated Nodosariidae and stilostomellids, biserial–uniserial pleurostomellids, triserial buliminids s.l., planispiral biconvex taxa such as Lenticulina spp., subglobular species (Globocassidulina subglobosa), and the trochospiral Oridorsalis umbonatus. Among epifaunal morphogroups, which make up 23.9 %–47.5 % of the assemblages, Nuttallides truempyi, Hanzawaia ammophila, Osangularia spp., Gyroidinoides beisseli, and Cibicidoides praemundulus are the most common taxa (Fig. 3).

The assemblages are moderately to relatively highly diverse throughout the study interval. The Fisher-α diversity index ranges between 11.84–25.47 (average 19.84). The heterogeneity H(S) index, with an average of 3.21, ranges from a minimum of 2.78 to a maximum of 3.46. BFAR values, with an average of 168.39, range between 323.82–105.04 specimens cm−2 kyr−1. The minimum values of these indices are reached between 75.3–75.5 rmcd, coinciding with the negative CIE and OIE, warmer temperatures, the highest XRF Fe area, lower CaCO3 values, and maximum dissolution, all of which mark the LLTM (Westerhold and Röhl, 2013; Westerhold et al., 2018) (Figs. 2, 3).

Changes in diversity and in the relative abundance of benthic foraminiferal taxa, coupled with corresponding shifts in geochemical proxies, enabled the identification of six intervals.

Interval 1 (76.6–76.017 rmcd/41.6552–41.5501 Ma) is characterized by the dominance (>10 %) of stilostomellids and Nodosariidae; other abundant (>4 %) infaunal taxa include Lenticulina spp., pleurostomellids, and G. subglobosa (Fig. 3). The calcareous epifaunal species N. truempyi is likewise dominant (Fig. 3). Diversity (Fisher-α average = 23.72) shows the highest values of the study record (>25) (Fig. 2). Heterogeneity of the assemblages (average of 3.34), the percentage of the superfamily Buliminacea and CaCO3, and the XRF Fe area show relatively stable values across interval 1 (Fig. 2). BFAR values (average of 180.97 specimens cm−2 kyr−1) range between 145.15–231.10 specimens cm−2 kyr−1, with a positive peak recorded at 76.10 rmcd (Fig. 2). The preservation of the benthic foraminiferal tests is very good across this interval, and it declines higher up (Fig. 6).

Interval 2 (76.017–75.775 rmcd/41.5501–41.5397 Ma) is characterized by the highest dominance of infaunal calcareous taxa across the study record, mostly due to the high percentage of buliminids s.l. (which make up to 39.83 % of the assemblages at 75.83 rmcd; Fig. 2) and stilostomellids (Fig. 3). The pleurostomellids, Nodosariidae, and G. subglobosa are abundant. The relative abundance of Lenticulina spp. decreases from abundant in interval 1 to common in interval 2, and the percentage of Chrysalogoniidae and Fursenkoina fusiformis slightly increases, showing their maximum values of the record across this interval (Fig. 3). N. truempyi shows the lowest percentage of the study record, but it still forms a dominant component of the assemblages. Diversity (Fisher-α average = 23.19) and heterogeneity of the assemblages (average of 3.28) are slightly lower than in interval 1. In contrast to the buliminids s.l., which show a remarkable peak and reach the highest values of the study record, the percentage of superfamily Buliminacea remains relatively constant (Fig. 2). The percentage of CaCO3 and the XRF Fe area also remain constant in this interval (Fig. 2). BFAR values drop down to an average of 113.61 specimens cm−2 kyr−1 (Fig. 2). The preservation of the benthic foraminiferal tests is good (Fig. 6).

Interval 3 (75.775–75.501 rmcd/41.5397–41.5279 Ma) is marked by gradual changes, including a gradual decrease in benthic δ13C values, the onset of a negative OIE in bulk sediment, increased XRF Fe area, and decreased CaCO3 values (from ∼ 75 % to ∼ 65 %) (Fig. 2). Infaunal calcareous taxa, including stilostomellids, still dominate the assemblages, but they show lower percentages than in previous intervals (Fig. 2). The infaunal Nodosariidae, pleurostomellids, G. subglobosa, Lenticulina spp., and O. umbonatus are abundant, and L. plummerae shows an abundance peak towards the top of this interval, from rare (<2 %) to abundant. The polymorphinids and the species Bulimina alazanensis, Bulimina trinitatensis, and Anomalinoides spissiformis show minor abundance peaks in this interval, and their percentages decrease towards interval 4. Among epifaunal taxa, the percentage of N. truempyi is significantly higher than in interval 2, reaching a maximum in the middle part of interval 3 (at 75.63 rmcd). Diversity (Fisher-α average = 20.19) and heterogeneity (average of 3.16) of the assemblages show a decreasing trend. The buliminids s.l. decrease, showing percentages similar to interval 1 (Fig. 2). BFAR values (average of 243.39 specimens cm−2 kyr−1) show a significant peak, reaching the highest values of the study record at 75.58 rmcd (323 specimens cm−2 kyr−1) (Fig. 2). Preservation of the benthic foraminiferal tests is good (Fig. 6).

Interval 4 (75.501–74.957 rmcd/41.5279–41.5042 Ma) corresponds to the interval previously identified as the LLTM at Site 1260 by Westerhold and Röhl (2013) and Westerhold et al. (2018) (Fig. 3). According to our age model, which is based on the CENOGRID (Westerhold et al., 2020), the event spans 23.7 kyr from its onset until background levels are re-established. Combining our results with those previous findings, the interval is divided into subinterval 4a, which comprises the first 27.8 cm/11.9 kyr (between 75.501–75.223 rmcd/41.5279–41.5160 Ma), and subinterval 4b, which includes the rest of the interval (26.6 cm/11.8 kyr, between 75.223 rmcd–74.957 rmcd/41.5160–41.5042 Ma) (Figs. 2, 3).

The definition of subinterval 4a is based on the lowest δ13Cbulk and δ18Obulk values and the highest XRF Fe values, which, along with a dark, clay-rich layer, indicate strong dissolution and relative enrichment of the clay fraction in the sediment across the LLTM (Röhl and Abrams, 2000; Röhl et al., 2007; Westerhold and Röhl, 2013; Westerhold et al., 2018) (Figs. 2, 3, 6). This subinterval shows the lowermost carbonate content of the study (decrease from ∼ 65 % to ∼ 37 %), with the minimum values recorded in the lowermost part (Westerhold et al., 2018) (Fig. 2) and the worst preservation of the study record (moderate at 75.32 and 75.47 rmcd; poor between 75.37–75.42 rmcd) (Fig. 6). Some benthic foraminifera could only be identified to the genus level (e.g. Anomalinoides spp., Nuttallides spp., Globocassidulina spp., Osangularia spp.) due to their poor preservation, mainly in samples from core 5, section 2, 19–21 cm (75.37 rmcd) and 24–26 cm (75.42 rmcd). Additionally, the sample at 75.37 rmcd contains very small specimens with thin, poorly preserved tests, and six specimens were classified as “trochospiral calcareous tentatively identified”.

Subinterval 4a shows the highest percentages of epifaunal morphogroups (47.54 % at 75.37 rmcd) and calcareous tests (100 % at 75.47 rmcd) and the lowest diversity, heterogeneity, and BFAR values, although these start to recover in the upper half of the interval (Fig. 2). The superfamily Buliminacea show the highest peak of the study record (17.52 % at 75.37 rmcd) and then decrease in abundance (Fig. 2). Although the stilostomellids are one of the dominant groups, their abundance shows the lowest values of the record in the middle part of this subinterval, at 75.37 rmcd (Fig. 3). The nodosariids and pleurostomellids, which are abundant, also show the lowest values of the record across this subinterval (Fig. 3). Some infaunal taxa (e.g. Bulimina glomarchallengeri, Chrysalogoniidae, Fissurina, Fursenkoina fusiformis from 75.47–75.37 rmcd, Karreriella bradyi) are absent, especially during the interval of minimum CaCO3 values (Fig. 3). In contrast, the relative abundances of O. umbonatus, Lenticulina, Pullenia eocenica, Alabamina dissonata, Gyroidinoides beisseli, and Hanzawaia ammophila increase (Fig. 3). The genus Nuttallides shows its maximum relative abundance at 75.37 rmcd, and the infaunal Bulimina simplex, Bolivina huneri, and Globocassidulina spp. show theirs at 75.47 rmcd (Fig. 3). The abundance of the epifaunal Anomalinoides spp. increases from above 75.37 rmcd (Fig. 3). The epifaunal genera Cibicidoides and Osangularia show higher values across the whole interval 4, and a peak in abundance of Osangularia is recorded at 75.42 rmcd (Fig. 3). The species Aragonia aragonensis, which was absent before the upper part of subinterval 4a, reaches its maximum values of the record (3.9 %) at 75.22 rmcd (Fig. 2).

Subinterval 4b marks the gradual recovery of the δ13C and δ18Obulk values, and the %CaCO3 and XRF Fe area show values similar to interval 2 (Fig. 2). The dominant taxa include stilostomellids, Nodosariidae, and N. truempyi; the latter two taxa show their highest relative abundance in the lower part of this subinterval (at 75.19 rmcd), decreasing upwards. Abundant taxa include G. subglobosa, Lenticulina spp., O. umbonatus, B. simplex, pleurostomellids, C. praemundulus, and Osangularia spp. (Fig. 3). A. aragonensis is a common species, and its abundance decreases upwards in intervals 5 and 6 (Fig. 3). B. glomarchallengeri reappears in subinterval 4b, increasing in abundance upwards (Fig. 3). The diversity and heterogeneity of the assemblages, the percentage of the superfamily Buliminacea, buliminids s.l., and the BFAR gradually increase towards the upper part of this subinterval (Fig. 2). The preservation of the benthic foraminiferal tests improves, and it is good, becoming very good in the upper part of the subinterval (Fig. 6).

In interval 5 (74.957–74.580 rmcd/41.5042–41.4871 Ma), the carbon and oxygen isotopic values and %CaCO3 increase and are similar to those in the pre-LLTM intervals (Fig. 2). Calcareous infaunal foraminifera show values similar to interval 1, with stilostomellids and Nodosariidae being the dominant taxa; B. semicostata, G. subglobosa, and Lenticulina spp. are abundant (Fig. 3). Among epifaunal taxa, N. truempyi is dominant, and A. dissonata, Cibicidoides, and Osangularia are abundant (Fig. 3). The diversity and heterogeneity of the assemblages increase, and in the upper part of this interval they reach values similar to those in interval 1 (Fig. 2). The BFAR shows a peak at 74.81 rmcd, followed by a decrease to values similar to those in subinterval 4b (Fig. 2). The abundance of B. semicostata, Anomalinoides spp., N. truempyi, and Nodosariidae increases across this interval, while the percentages of Lenticulina spp. and stilostomellids decrease (Fig. 3). Turrillina brevispira, which was common before the onset of the LLTM, decreases its abundance gradually, reaching its lowest values in this interval (Fig. 3). The preservation of the benthic foraminiferal tests is very good (Fig. 6).

Interval 6 (74.580–74.4 rmcd/41.4871–41.4789 Ma) shows carbon and oxygen isotope values, %CaCO3, XRF Fe area, BFAR values, and percentage of infaunal calcareous foraminifera similar to the upper part of interval 5 (Fig. 2). The percentages of N. truempyi and the stilostomellids slightly increase across interval 6 (Fig. 3). The preservation of the benthic foraminiferal tests is very good (Fig. 6).

The six stratigraphic intervals are differentiated in the Q-mode DCA plot (Fig. 5). Samples from subinterval 4a are significantly separated from the rest, showing the most positive values along the x axis. Samples from subinterval 4b show intermediate values, and the samples from the other intervals (1–3, 5, 6) score the most negative values along this axis.

4.2 Other components of the sediment samples

4.2.1 Semi-quantitative analyses of radiolarians, foraminifera, and sponge spicules

The semi-quantitative analysis of other components of the sediment (Fig. 6) shows that the proportion of radiolarians is inversely proportional to that of planktic foraminifera. The relative abundance of radiolarians increases in subinterval 4a, where the percentage of planktic foraminifera decreases. The relative abundance of benthic foraminifera is very low throughout the entire study interval, as expected in a deep-sea setting. The proportion of sponge spicules is slightly higher than that of benthic foraminifera throughout the study interval, reaching its highest values in subinterval 4a.

4.2.2 Quantitative analyses of fish teeth

The quantitative analysis of fish teeth, performed on the same sample aliquot used for foraminifera assemblage studies, shows relatively low values throughout the entire study interval (Fig. 6). The exception is subinterval 4a, which exhibits the highest peak in the number of fish teeth per gram of sediment, particularly in the lowermost 10.4 cm of the LLTM, coinciding with significant CaCO3 dissolution.

Figure 6XRF core scanning Fe intensities (Westerhold and Röhl, 2013), coulometric CaCO3 content (Westerhold et al., 2018), semi-quantitative analyses (%) of various microfossil groups (Table S3), quantitative analyses on fish teeth (number of fish teeth per gram of sediment) (Table S3), quantitative analyses of benthic foraminifera (% calcareous and agglutinated tests) (Table S2), and preservation of benthic foraminiferal tests (Table S4) at ODP Site 1260, plotted against depth (rmcd). The dashed black line marks the limit between subintervals 4a and 4b, and the red one corresponds to the depths of maximum CaCO3 corrosivity.

5.1 Palaeobathymetry

Benthic foraminiferal assemblages at ODP Site 1260 are dominated by calcareous taxa and indicate deposition above the calcite compensation depth. Nuttallides truempyi and stilostomellids are dominant at this site, and they are predominantly found at lower bathyal and abyssal depths during the Eocene, with the latter most common between 1000 and 3000 m (Pflum and Frerichs, 1976; Tjalsma and Lohmann, 1983; Katz et al., 2003). Abundant and common species at this site, such as Globocassidulina subglobosa, Anomalinoides spissiformis, Bulimina semicostata, Bulimina trinitatensis, Cibicidoides praemundulus, and Nonion havanense, are typical of lower bathyal to abyssal depths (Tjalsma and Lohmann, 1983; Van Morkhoven et al., 1986; Hayward et al., 2001, 2004, 2010). Other bathyal to abyssal species include Oridorsalis umbonatus, Bulimina glomarchallengeri, and Aragonia aragonensis (Tjalsma and Lohmann, 1983; Van Morkhoven et al., 1986; Alegret et al., 2009; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2018). Middle bathyal to abyssal taxa (Anomalinoides semicribratus, pleurostomellids) (Tjalsma and Lohmann, 1983; Van Morkhoven et al., 1986; Bignot, 1998) are also present. Turrillina brevispira is an outer neritic to lower bathyal species, and it also occurs at abyssal sites (Van Morkhoven et al., 1986).

The upper depth limit of Globocassidulina subglobosa was located at upper bathyal depths during the Eocene; Bulimina trinitatensis, Nuttallides truempyi, Osangularia mexicana, and Hanzawaia ammophila had their upper depth limit at 500–700 m, and Alabamina dissonata and Cibicidoides grimsdalei had their upper depth limit at 1000–1500 m (Van Morkhoven et al., 1986).

These data indicate a minimum palaeodepth at lower bathyal settings (1000–2000 m; Van Morkhoven et al., 1986), and the record of specific foraminifera points to an upper abyssal palaeodepth (2000–3000 m; Van Morkhoven et al., 1986). Key evidence includes the identification of Hanzawaia ammophila and Bolivina huneri, which are also abundant at abyssal environments (Van Morkhoven et al., 1986; Müller-Merz and Oberhänsli, 1991; Grira et al., 2018), the lower bathyal to upper abyssal Osangularia mexicana (Tjalsma and Lohmann, 1983), and the primarily abyssal species Alabamina dissonata (Tjalsma and Lohman, 1983; Van Morkhoven et al., 1986). The dominance of Nuttallides truempyi (Müller-Merz and Oberhänsli, 1991) also supports the upper abyssal palaeodepth. This interpretation is consistent with previous palaeodepth estimates of ∼ 2500 m for Site 1260 (Erbacher et al., 2004; Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold and Röhl, 2013; Westerhold et al., 2018).

5.2 Palaeoenvironmental interpretation

Benthic foraminiferal assemblages from this upper abyssal environment, where calcareous infaunal morphogroups are more abundant (average 66.1 %) than epifaunal ones (average 33.9 %) (Fig. 2), point to oligo-mesotrophic conditions according to the TROX model of Jorissen et al. (1995). This interpretation is supported by low BFAR values (average 168.4 specimens cm−2 kyr−1), the common occurrence of the oligotrophic species N. truempyi (Thomas et al., 2000; Arreguín-Rodríguez and Alegret, 2016; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020), and the low relative abundance of buliminids s.l. (average 28.4 % of the assemblages) and the superfamily Buliminacea (average 8.6 %) (Figs. 2, 3, 7), which in the modern oceans are most common at sites with an abundant food supply (e.g. Fontanier et al., 2002).

Figure 7Carbon and oxygen stable isotopes measured on bulk carbonate (Sexton et al., 2006; Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold et al., 2018), XRF core scanning Fe intensities (Westerhold and Röhl, 2013), and coulometric CaCO3 content (Westerhold et al., 2018); percentages of radiolaria (%R) and planktic foraminifera (%P.f) and benthic foraminiferal analyses (this study; percentage of calcareous and agglutinated foraminifera, preservation of the tests, benthic foraminiferal accumulation rates (BFAR), diversity of the assemblages, and percentage of selected benthic foraminiferal taxa) at ODP Site 1260, plotted against age (Ma). The dashed black line marks the limit between subinterval 4a and 4b, and the red one corresponds to the depths of maximum dissolution.

Interval 1 (76.6–76.017 rmcd/41.6552–41.5501 Ma) contains diverse benthic foraminiferal assemblages with well-preserved calcareous infaunal foraminifera. The abundance of shallow infaunal stilostomellids and Nodosariidae, the oligotrophic species N. truempyi, the oxic indicator G. subglobosa, and pleurostomellids (Figs. 3, 7) indicates stable oligo-mesotrophic conditions and well-oxygenated bottom waters (Jorissen et al., 2007; Palmer et al., 2020; Alegret et al., 2021b).

A change in trophic conditions is inferred for interval 2 (76.017–75.775 rmcd/41.5501–41.5397 Ma). More organic matter particles in suspension, as a result of higher-energy bottom-water currents, may have favoured infaunal suspension-feeders (e.g. stilostomellids) over epifaunal taxa, decreasing the relative proportion of other epifaunal species such as N. truempyi. The interpretation of the lower BFAR values observed in interval 2 (ca. 114 specimens cm−2 kyr−1) in terms of export productivity is not straightforward. It has been suggested that its use in settings with biophysical coupling of food supply to the current regime cannot be assumed (e.g. Genin, 2004; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2016), and a solid interpretation of this index thus cannot be provided due to the higher-energy bottom-water currents interpreted in interval 2.

Interval 3 (75.775–75.501 rmcd/41.5397–41.5279 Ma) is marked by a gradual decrease in the δ18Obulk, %CaCO3, and diversity and heterogeneity of the assemblages, along with increased δ13Cbulk, XRF Fe, and BFAR values, which are interpreted as the onset of warming and environmental instability prior to the LLTM (Figs. 2, 3, 7). Increased δ13C values could indicate enhanced primary productivity, as a result of accelerated phytoplankton growth and metabolic rates within optimal temperature ranges (Grant and Dickens, 2002). Increased BFAR values point to higher export productivity across this interval (Figs. 2, 7). This is further supported by a qualitative study of samples from interval 3, which reveals larger individuals within the benthic foraminiferal assemblages, as a result of enhanced food supply reaching the seafloor. The higher percentage of L. plummerae (Figs. 2, 7), whose abundance increased during the Middle Eocene Climatic Optimum (MECO) warming in the Southern Ocean, also points to an increased nutrient supply to the seafloor (Moebius et al., 2014). Infaunal morphogroups did not become more abundant in this interval, likely due to increased CaCO3 corrosivity acting as the limiting factor for the foraminiferal assemblages. The ∼ 15 % drop in %CaCO3, along with the increase in abundance of CaCO3 corrosive-resistant taxa like Lenticulina spp., N. truempyi, or O. umbonatus (Tjalsma and Lohmann, 1983; Alegret and Thomas, 2009; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020), suggest more CaCO3-corrosive bottom waters in interval 3 (Fig. 2, 7). A. spissiformis, a highly resilient species (Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020) with intermediate resistance to dissolution (Nguyen et al., 2009), also increased in abundance. This scenario suggests that the increase in CaCO3 corrosivity was the primary limiting factor for infaunal morphogroups in interval 3. The majority of the infaunal foraminifera in this interval are characterized by calcareous uniserial, biserial, and triserial hyaline taxa that exhibit lower resistance to CaCO3 dissolution (e.g. Nguyen et al., 2009; Putra et al., 2023). In contrast, the epifaunal species Nuttallides truempyi, which has been argued to be CaCO3 corrosive-resistant (Thomas, 1998), increased in interval 3. The qualitative study of benthic foraminiferal test preservation, which shifts from good to moderate by the end of this interval, along with the increased percentage of radiolarians and fish teeth and a decrease in planktic foraminifera, supports increased CaCO3 corrosivity in interval 3 (Figs. 6, 7).

Interval 4 (75.501–74.957 rmcd/41.5279–41.5042 Ma) corresponds to the LLTM, which was identified at ODP Site 1260 based on inorganic geochemistry, XRF-derived iron intensity records, and cyclostratigraphy (Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold and Röhl, 2013; Westerhold et al., 2018). The LLTM is associated with the highest insolation value of the last 45 Ma at 41.52 Ma, along with a negative CIE (0.86 ‰ in bulk sediment and 1.26 ‰ in planktic foraminifera) and a negative OIE (1.8 ‰ in bulk sediment and 0.3 ‰ in planktic foraminifera), the lowest percentages of CaCO3, and the highest values of XRF Fe area (Figs. 2, 7). It has been subdivided into subintervals 4a and 4b, according to previous studies and our analysis of the benthic foraminiferal assemblages. The slight differences in the duration of this interval and its different phases are attributed to the age model, since Westerhold et al. (2018) used the astronomical age model of Westerhold and Röhl (2013), and the age model of the present study is based on the CENOGRID (Westerhold et al., 2020) in order to more precisely compare the response of benthic assemblages with other publications on benthic foraminifera across the LLTM (Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020; Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2024).

Subinterval 4a, spanning approximately 12 kyr, is characterized by a lower carbonate content, indicative of CaCO3 corrosivity, and the warmest temperatures of the LLTM (Westerhold et al., 2018), as shown by the lowest δ18Obulk values in the lower half of this subinterval, followed by gradual recovery. Benthic assemblages show their lowest diversity and heterogeneity (Figs. 2, 7), indicating the highest environmental stress of the LLTM, likely related to CaCO3-corrosive bottom waters resulting from warming and changes in the carbon cycle. A qualitative observation of the assemblages shows a decrease in size of benthic foraminiferal tests, consistent with environmental stress. Alternatively, lower diversity might simply be related to a taphonomic bias due to CaCO3 corrosivity. Although infaunal taxa are typically more shielded from corrosive waters than epifaunal taxa due to carbonate supersaturation in pore waters (e.g. Ilyina and Zeebe, 2012; Foster et al., 2013; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2016), intense bottom-water corrosivity is inferred during the LLTM at Site 1260, as both morphogroups show the worst preservation of their tests across subinterval 4a (Figs. 6, 7) (Table S4). Infaunal taxa with morphologies less resistant to CaCO3 corrosivity (e.g. uniserial stilostomellids or nodosariids) decrease in abundance, and morphologies that are more resistant to carbonate corrosivity, like planispiral (Lenticulina) or trochospiral taxa (Oridorsalis umbonatus), among others (Nonion, Globocassidulina, Pullenia) (e.g. Nguyen et al., 2009; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020; Putra et al., 2023), become more abundant or show abundance peaks (Figs. 3, 7). Among epifaunal morphogroups that are less susceptible to carbonate-corrosive waters, the trochospiral Nuttallides truempyi dominates the assemblages, and Osangularia, Anomalinoides, Hanzawaia, Alabamina, Gyroidinoides or Cibicidoides are abundant (Figs. 3, 7) (e.g. Nguyen et al., 1990; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020; Putra et al., 2023).

The integration of benthic foraminiferal results with the quantitative and semi-quantitative analyses of the other components of the sediment supports the scenario of CaCO3 corrosivity during the peak warming. The semi-quantitative analysis shows a drastic decrease in the percentage of planktic foraminifera, which are more susceptible to dissolution than benthic foraminifera (Nguyen et al., 2009), along with increased percentages of siliceous components such as radiolaria or sponge spicules. Regarding fish teeth, which are more resistant to carbonate dissolution due to their high phosphate content, a higher number of fish teeth per gram of sediment has been recorded (Figs. 6, 7). Benthic foraminifera also point to more corrosive bottom waters, as the worst preservation of their tests is observed across subinterval 4a (Figs. 6, 7) (Table S4).

The lower BFAR values in subinterval 4a are likely a result of taphonomic bias due to CaCO3 corrosivity. One might argue that the decreased BFAR could also be linked to reduced export productivity resulting from changes in primary productivity (linked to excessive insolation or carbonate dissolution affecting primary producers) and/or increased organic matter remineralization in the water column under higher temperatures. However, CaCO3 dissolution led to a taphonomic bias of the assemblages, which were selectively enriched in CaCO3 corrosion-resistant taxa (infaunal trochospiral and planispiral taxa, such as Lenticulina and Oridorsalis, and epifaunal taxa such as Nuttallides, Alabamina, or Osangularia), obscuring the environmental signal of lower export productivity. Some of the species that peak in abundance in subinterval 4a, such as O. umbonatus and N. truempyi, have been documented to thrive under oligotrophic and corrosive conditions (Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2016; Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020), and C. praemundulus, G. beisseli, and N. havanense are high-resilience species (Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020). Osangularia and B. huneri have been described as stress-tolerant taxa, and B. huneri has been related to low-quality organic matter (D'haenens et al., 2012, Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2019). A. aragonensis is an opportunistic species that commonly thrives during Paleogene hyperthermal events (Thomas, 1990, 1998, 2003; Alegret et al., 2009, 2016, 2018; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2016), and B. simplex was also documented during an early Eocene hyperthermal event (Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2016). A more robust palaeoenvironmental interpretation of this interval, however, is limited by the taphonomic effects of carbonate dissolution on the assemblages.

Finally, one might wonder why agglutinated foraminifera did not increase in abundance in interval 4a, coinciding with the lowermost %CaCO3 values. Agglutinated taxa were very scarce across all the study intervals, and calcareous, CaCO3 corrosion-resistant taxa were more abundant, particularly in interval 4a. We argue that CaCO3 corrosivity introduced a taphonomic bias in the assemblages in interval 4a, affecting preservation of the foraminiferal tests (Fig. 6), but that dissolution was not pervasive at the seafloor. Under strong CaCO3 dissolution, assemblages would only contain organic-cemented agglutinated foraminifera.

Subinterval 4b represents the gradual recovery of the oxygen isotopes and a faster recovery of the carbon isotopes and the %CaCO3 and XRF values to background values (similar to intervals 1 and 2). B. simplex and C. praemundulus are still abundant, and A. aragonensis is common, pointing to the persistence of the environmental stress. In contrast, the percentages of some taxa that dropped in relative abundance (e.g. F. fusiformis, L. plummerae, Nodosariidae, Glandulonodosariidae) or temporarily disappeared (A. semicribratus, B. glomarchallengeri, Chrysalogoniidae, Fissurina spp., Martinottiella sp.) during subinterval 4a increase in subinterval 4b (Figs. 3, 7). Diversity of the assemblages and BFAR values gradually recover, but they are still below pre-LLTM values. The preservation of the tests becomes good (Figs. 6, 7). The percentage of planktic foraminifera reaches values similar to interval 1, and the percentage of siliceous components and the number of fish teeth decrease (Figs. 6, 7). These results indicate that, although environmental stress persisted, CaCO3 corrosivity did not play a significant role during interval 4b, and temperatures were cooler than in subinterval 4a, accounting for the slight – but still partial – recovery of the BFARs and export productivity.

Intervals 5 (74.957–74.580 rmcd/41.5042–41.4871 Ma) and 6 (74.580–74.4 rmcd/41.4871–41.4789 Ma) are characterized by δ13Cbulk values that are similar to pre-LLTM intervals and δ18Obulk values that are slightly more positive, suggesting the return to cooler temperatures (Figs. 2, 7). The XRF Fe area shows lower values, and the %CaCO3 shows the highest values of the record, pointing to CaCO3-saturated bottom waters (Figs. 2, 7). This is supported by the preservation of benthic foraminifera tests, which is very good in both intervals. In addition, the percentage of planktic foraminifera from interval 5 is higher than in the previous intervals, and the percentage of radiolaria shows the opposite trend (Figs. 6, 7). Environmental stress at the seafloor decreased, as inferred from the gradual increase in diversity and heterogeneity of the benthic assemblages, and their taxonomic composition is similar to intervals 1 and 2 (Fig. 2), suggesting the return to stable, oligo-mesotrophic conditions at the seafloor. The dominance of stilostomellids and Nodosariidae is consistent with this stable scenario.

The Q-mode statistical analysis supports the environmental perturbation related to the LLTM at ODP Site 1260, although the interpretation of the DCA axes (Fig. 5) is complex. Subinterval 4a, which reflects the most significant environmental perturbation associated with CaCO3 corrosivity, shows the highest values along axis x. Subinterval 4b, associated with less environmental stress, scores intermediate values along this axis, and the samples from the rest of the study (pre- and post-LLTM event), with more stable conditions at the seafloor, score the lowest values along axis 1.

5.3 Comparison with previous LLTM studies

The LLTM was first described at ODP Site 1260 in the equatorial Atlantic Ocean (Edgar et al., 2007; Westerhold and Röhl, 2013) and later identified in the South Atlantic Ocean ODP Site 702 (Islas Orcadas Rise) and ODP Site 1263 (Walvis Ridge) (Westerhold et al., 2018). The LLTM at these Atlantic sites is marked by a negative CIE and OIE, a pronounced peak in Fe intensity, and a decrease in CaCO3 content.

Our study on the response of benthic foraminiferal assemblages to the LLTM significantly expands the available data at Site 1260. Documenting the benthic foraminiferal turnover is crucial to understand how hyperthermal events associated with exceptionally strong insolation affect the marine ecosystems and the climate system dynamics, but so far there are only three studies available. This is partly related to the fact that the LLTM is difficult to identify in deep-sea sediments due to its short duration. The compilation of the benthic foraminiferal results from the three studies available, two from the Atlantic Ocean (the middle bathyal Cape Oyambre section, northeast Atlantic (Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al., 2018) and the lower bathyal ODP Site 702 in the South Atlantic (Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020)) and one from the southwestern Pacific (IODP Site U1508 in the Tasman Sea; Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2024), reveals key similarities and differences across diverse oceanic basins and depths, thereby advancing our knowledge on the impact of hyperthermal events on deep-sea environments.

In these three studies, the LLTM is marked by the negative CIE and OIE (suggesting warming of the water column and changes in the carbon cycle), decreased carbonate content, and decreased diversity of the benthic foraminiferal assemblages, indicative of environmental stress. These results align with the results from ODP Site 1260.

The shallowest site is located in the continental marginal setting of Cape Oyambre, where Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al. (2018) reported the dominance of clay minerals and quartz grains across the LLTM, alongside sea-surface eutrophication attributed to elevated continental nutrient runoff. The increased nutrient flux to the seafloor, related to the enhanced hydrological cycle during the LLTM, correlates with the research at Site 1260 of Westerhold and Röhl (2013), which highlighted exceptionally high insolation levels at 41.5 Ma. No evidence of carbonate dissolution was found in the calcareous nannofossils and benthic foraminifera from Oyambre, and the decrease in carbonate content was mainly related to dilution of the pelagic carbonate sedimentation (Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al., 2018). Benthic foraminifera point to a higher input of organic matter to the seafloor under oxic conditions (Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al., 2018).

In contrast, benthic foraminifera indicate more oligotrophic conditions and lower BFAR values at the deep-sea sites (i.e. Atlantic Sites 702 and 1260 and Pacific Site U1508). Rivero-Cuesta et al. (2020) interpreted the lower BFAR values at Site 702 as indicative of increased metabolic rates of heterotroph organisms under warmer temperatures, as limited food resources cause a population decline. At Site U1508, the warming-induced stratification (which led to the proliferation of dysoxic taxa) and increased remineralization of the organic matter in the water column led to decreased export productivity (Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2024). At Site 1260, CaCO3 corrosivity may have triggered decreased primary and export productivity. The three studies report a decrease in CaCO3 content, but our study at Site 1260 is the only one that documents carbonate dissolution. The dissolution is reflected by remarkable changes in previously published XRF and carbonate content analyses (Westerhold and Röhl, 2013; Westerhold et al., 2018), in the components of the sediment (e.g. drastic decrease in planktic foraminifera, increase in % radiolaria and in the number of fish teeth g−1), and by changes in the benthic foraminiferal assemblages, which display the worst test preservation of the study record during the warming event. Additionally, benthic assemblages at Site 1260 are dominated by corrosive-resistant taxa (e.g. N. truempyi, O. umbonatus), along with infaunal taxa and some rotaliines. Infaunal organisms live buried in the sediment, where pore waters are typically more carbonate-saturated and less corrosive than the overlying bottom waters (Foster et al., 2013; Arreguín-Rodríguez et al., 2021), and the test characteristics of infaunal and epifaunal rotaliines point to an intermediate resistance to dissolution (Nguyen et al., 2009). At Sites 702 (Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020) and U1508 (Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2024), the authors documented increased CaCO3 corrosivity of bottom waters but no CaCO3 dissolution at the seafloor. The biotic turnover at Site 702 (Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020) indicates changes in the type of organic matter reaching the seafloor during the LLTM, and benthic assemblages at Sites 1260 and U1508 point to a decrease in the organic matter flux to the seafloor. Decreased oxygenation of bottom waters, due to warming-induced stratification of the water column, has only been reported at the Pacific site, as suggested by changes in benthic foraminiferal assemblages (e.g. the decrease in the oxic species G. subglobosa and increased abundance of the dysoxic genus Lenticulina) and organic geochemistry (e.g. BIT index, Methane Index, AOM index, GDGT-2/3 ratio) (Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2024).

This compilation of the benthic foraminiferal response to the LLTM highlights different responses to the same forcing factor, supporting the hypothesis that the palaeoceanographic setting may account for the observed divergences (Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2024). The biotic response to the LLTM at the shallowest site (the Atlantic Cape Oyambre section), located on a continental margin, was significantly different from the deeper Atlantic sites. Intxauspe-Zubiaurre et al. (2018) documented an increased nutrient flux to the seafloor during the LLTM as an effect of the increased hydrological cycle, which is associated with the highest insolation. The deeper sites are open-ocean settings and indicate more oligotrophic conditions at the seafloor across the LLTM. It is important to note that the consequences of the LLTM and the biotic response were likely shaped by the different oceanic circulation patterns during the Eocene. Site U1508 is located in the Tasman Sea, a crucial area where the tectonics, and thus ocean circulation, were highly variable during the Eocene, and still presents gaps of knowledge (Sutherland et al., 2019, 2020; Alegret et al., 2021a, 2021b; Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2025a). Consequently, it is difficult to draw conclusions when comparing Site U1508 with the Atlantic locations. Site 702 (Rivero-Cuesta et al., 2020) was located in the South Atlantic, and Site 1260 was located in the equatorial Atlantic, with different environmental conditions related to a wide variety of factors such as the continent distribution (and proximity to the continental areas) and the resulting deep-water formation and ocean circulation. Model simulations (e.g. Zhang et al., 2022; Pineau et al., 2025) suggest that deep-water masses that circulated in the Atlantic during the early and middle Eocene were likely formed in the Southern Ocean, as the palaeogeography of the North Atlantic at the time prevented its own deep-water formation. We speculate that under this palaeoceanographic scenario, South Atlantic Site 702, located closer to the Southern Ocean (Fig. 1), may have been influenced by younger, less acidified (e.g. Tripati and Elderfield, 2005; Bohaty et al., 2009; Bijl et al., 2010) water masses than Site 1260 (equatorial Atlantic), thus limiting carbonate dissolution on the seafloor. Further in-depth studies of benthic foraminiferal assemblages, integrated with multiproxy analyses, are needed at a regional scale to understand the influence of deep-ocean circulation on the LLTM effects in the Atlantic basin.

The Late Lutetian Thermal Maximum (LLTM) is a middle Eocene hyperthermal event linked to the highest insolation values of the last 45 million years on Earth's surface. At ODP Site 1260, in the equatorial western Atlantic, the LLTM is defined by a sharp negative excursion of δ18O and δ13C, and it coincides with a dark, clay-rich layer with low CaCO3 values, indicating carbonate dissolution during the event. Detailed quantitative analyses of the benthic foraminiferal turnover at this upper abyssal site complement previous studies on the LLTM, improving the understanding of the effects of global warming in the largest habitat on Earth, the deep seafloor.

Decreased diversity of benthic foraminiferal assemblages indicates environmental stress at the seafloor during the LLTM, associated with increased CaCO3 corrosivity of bottom waters. Low %CaCO3 values, the increased relative abundance of corrosive-resistant taxa, the poor preservation of the tests, the increase in the number of fish teeth per gram of sediment and in the percentage of siliceous components (radiolaria and sponge spicules), and the decrease in planktic foraminifera (which are more susceptible to dissolution) also indicate CaCO3 corrosivity during the first half of the LLTM, followed by rapid recovery. Reduced export productivity, associated with decreased primary productivity or increased organic matter remineralization in the water column, may have contributed to the environmental stress during the peak warming of the LLTM.

The comparison with other studies that document the benthic foraminiferal response to the LLTM expands our knowledge on the effects of global warming in the deep-sea ecosystems. Oligotrophic conditions at the seafloor have been reported across the LLTM at deep-sea Atlantic Sites 702 and 1260 and at Pacific Site U1508. In contrast, a shallower site near a continental margin in the NE Atlantic was more influenced by changes in runoff and terrestrial input, resulting in enhanced delivery of organic matter to the seafloor. The scarce studies available led us to conclude that the response of the benthic foraminiferal assemblages to the LLTM was strongly influenced by the palaeogeographic and palaeoceanographic setting.

Data generated in this study are available in the Supplement and at Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17599663 (Peñalver-Clavel et al., 2025b).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-44-713-2025-supplement.

IPC: writing (original draft and review and editing), investigation, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization. TW: writing (review and editing), data curation. LA: writing (review and editing), sample curation, conceptualization, supervision.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Journal of Micropalaeontology. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We acknowledge the use of Servicio General de Apoyo a la Investigación-SAI, Universidad de Zaragoza, and Cristina Gallego for SEM imaging. We acknowledge funding from the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) to the International Subcommission on Paleogene Stratigraphy. This research used samples and data provided by the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP).

This research has been supported by projects PID2023-149894OB-I00 (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, FEDER, UE) and E33_23R (Gobierno de Aragón). IP was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCIN) (FPI grant PRE2020-092638).

This paper was edited by Sev Kender and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Alegret, L. and Thomas, E.: Upper cretaceous and lower Paleogene benthic foraminifera from northeastern Mexico, Micropaleontology, 47, 269–316, 2001.

Alegret, L. and Thomas, E.: Food supply to the seafloor in the Pacific Ocean after the Cretaceous/Paleogene boundary event, Mar. Micropaleontol., 73, 105–116, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2009.07.005, 2009.

Alegret, L., Ortiz, S., Orue-Etxebarria, X., Bernaola, G., Baceta, J.I., Monechi, S., Apellaniz, E., and Pujalte, V.: The Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum: new data from the microfossil turnover at Zumaia section, Palaios, 24, 318–328, https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2008.p08-057r, 2009.

Alegret, L., Ortiz, S., Arenillas, I., and Molina, E.: What happens when the ocean is overheated? The foraminiferal response across the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum at the Alamedilla section (Spain), GSA Bull., 122, 1616–1624, 2010.

Alegret, L., Reolid, M., and Vega Pérez, M.: Environmental instability during the latest Paleocene at Zumaia (Basque-Cantabric Basin): the herald of the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 497, 186–200, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.02.018, 2018.

Alegret, L., Ortiz, S., Arreguín-Rodríguez, G.J., Monechi, S., Millán, I., and Molina, E.: Microfossil turnover across the uppermost Danian at Caravaca, Spain: Paleoenvironmental inferences and identification of the latest Danian event, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 463, 45–59, 2016.

Alegret, L., Arreguín-Rodríguez, G. J., Trasviña-Moreno, C. A., and Thomas, E.: Turnover and stability in the deep sea: benthic foraminifera as tracers of Paleogene global change, Glob. Planet. Chang., 196, 103372, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103372, 2021a.

Alegret, L., Harper, D. T., Agnini, C., Newsham, C., Westerhold, T., Cramwinckel, M. J., Dallanave, E., Dickens, G. R., and Sutherland, R.: Biotic response to early Eocene warming events: integrated record from offshore Zealandia, North Tasman Sea, Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol., 36, e2020PA004179, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020PA004179, 2021b.

Arreguín-Rodríguez, G. J. and Alegret, L.: Deep-sea benthic foraminiferal turnover across early Eocene hyperthermal events at Northeast Atlantic DSDP site 550, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 451, 62–72, 2016.

Arreguín-Rodríguez, G. J., Alegret, L., and Thomas, E.: Late Paleocene-middle Eocene benthic foraminifera on a Pacific seamount (Allison Guyot, ODP Site 865): Greenhouse climate and superimposed hyperthermal events, Paleoceanography, 31, 346–364, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015PA002837, 2016.

Arreguín-Rodríguez, G. J., Thomas, E., D'haenens, S., Speijer, R. P., and Alegret, L.: Early Eocene deep-sea benthic foraminiferal faunas: recovery from the Paleocene Eocene thermal maximum extinction in a greenhouse world, PLoS ONE 13, e0193167, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193167, 2018.

Arreguín-Rodríguez, G. J., Barnet, J., Leng, M., Littler, K., Kroon, D., Thomas, E., and Alegret, L.: Benthic foraminiferal turnover across the Dan-C2 event in the eastern South Atlantic Ocean (ODP Site 1262), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 572, 110410, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110410, 2021.

Arreguín-Rodríguez, G. J., Thomas, E., and Alegret, L.: Some like it cool: Benthic foraminiferal response to Paleogene warming events, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 593, 110925, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.110925, 2022.

Bignot, G.: Middle Eocene benthic foraminifers from Holes 960A and 960C, central Atlantic Ocean, edited by: Mascle, J., Lohmann, G.P., and Moullade, M., Proc. ODP, Sci. Results, 159: College Station, TX (Ocean Drilling Program), 433–444, https://doi.org/10.2973/odp.proc.sr.159.017.1998, 1998.

Bijl, P. K., Houben, A. J. P., Schouten, S., Bohaty, S. M., Sluijs, A., Reichart, G.-J., Damste, J. S. S., and Brinkhuis, H.: Transient middle Eocene atmospheric CO2 and temperature variations, Science, 330, 819–821, 2010.

Bohaty, S. M. and Zachos, J. C.: Significant Southern Ocean warming event in the late middle Eocene, Geology, 31, 1017–1020, 2003.

Bohaty, S. M., Zachos, J. C., Florindo, F., and Delaney, M. L.: Coupled greenhouse warming and deep-sea acidification in the middle Eocene, Paleoceanography, 24, PA2207, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008PA001676, 2009.

Boltovskoy, E. and Totah, V. I.: Preservation index and preservation potential of some foraminiferal species, Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 22, 267–273, 1992.

Buzas, M. A., Culver, S. J., and Jorissen, F. J.: A statistical evaluation of the microhabitats of living (stained) infaunal benthic foraminifera, Mar. Micropaleontol., 20, 311–320, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-8398(93)90040-5, 1993.

Corliss, B. H.: Morphology and microhabitat preferences of benthic foraminifera from the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, Mar. Micropaleontol., 17, 195–236, 1991.

Corliss, B. H. and Chen, C.: Morphotype patterns of Norwegian Sea deep-sea benthic foraminifera and ecological implications, Geology, 16, 716–719, 1988.

D'haenens, S., Bornemann, A., Stassen, P., and Speijer, R. P.: Multiple early Eocene benthic foraminiferal assemblage and δ13C fluctuations at DSDP Site 401 (Bay of Biscay – NE Atlantic), Mar. Micropaleontol., 88–89, 15–35, 2012.

Edgar, K. M., Wilson, P. A., Sexton, P. F., and Suganuma, Y.: No extreme bipolar glaciation during the main Eocene calcite compensation shift, Nature, 448, 908–911, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06053, 2007.

Erbacher, J., Mosher, D. C., Malone, M. J., et al.: Proc. ODP, Init. Repts., 207: College Station, TX (Ocean Drilling Program), https://doi.org/10.2973/odp.proc.ir.207.2004, 2004.

Fontanier, C., Jorissen, F. J., Licari, L., Alexandre, A., Anschutz, P., and Carbonel, P.: Live benthic foraminiferal faunas from the Bay of Biscay: faunal density, composition and microhabitats, Deep-Sea Res. I, 49, 751–785, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-0637(01)00078-4, 2002.

Foster, L. C., Schmidt, D. N., Thomas, E., Arndt, S., and Ridgwell, A.: Surviving rapid climate change in the deep sea during the Paleogene hyperthermals, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 9273–9276, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1300579110, 2013.

Foster, G. L., Hull, P., Lunt, D. J., and Zachos, J. C.: Placing our current “hyperthermal” in the context of rapid climate change in our geological past, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 376, 20170086, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2017.0086, 2018.

Genin, A.: Bio-physical coupling in the formation of zooplankton and fish aggregations over abrupt topographies, J. Mar. Syst., 50, 3–20, 2004.

Gooday, A. J.: Benthic foraminifera (protista) as tools in deep-water palaeoceanography: environmental influences on faunal characteristics, Adv. Mar. Biol., 46, 1–90, 2003.

Grant, K. M. and Dickens, G. R.: Coupled productivity and carbon isotope records in the southwest Pacific Ocean during the late Miocene–early Pliocene biogenic bloom, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 187, 61–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-0182(02)00508-4, 2002.

Grira, C., Karoui-Yaakoub, N., Negra, M. H., Rivero-Cuesta, L., and Molina, E.: Paleoenvironmental and ecological changes during the Eocene-Oligocene transition based on foraminifera from the Cap Bon Peninsula in North East Tunisia, J. Afr. Earth Sci., 143, 145–161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2018.02.013, 2018.

Hammer, Ø. and Harper, D.: Paleontological Data Analysis, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 351 pp., ISBN 1 4051 1544 0, 2005.

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T., and Ryan, P. D.: PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis, Paleontol. Electron., 4, 1–9, 2001.

Hayward, B. W., Carter, R., Grenfell, H. R., and Hayward, J. J.: Depth distribution of recent deep-sea benthic foraminifera east of New Zealand, and their potential for improving paleobathymetric assessments of Neogene microfaunas, N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys., 44, 555–587, 2001.

Hayward, B. W., Grenfell, H. R., Carter, R., and Hayward, J. J.: Benthic foraminiferal proxy evidence for the Neogene palaeoceanographic history of the Southwest Pacific, east of New Zealand, Mar. Geol., 205, 147–184, 2004.

Hayward, B. W., Grenfell, H. R., Sabaa, A. T., Neil, H., and Buzas, M. A.: Recent New Zealand deepwater benthic foraminifera: taxonomy, ecologic distribution, biogeography, and use in paleoenvironmental assessment, GNS Sci. Monogr., 26, 363, 2010.

Hayward, B. W., Kawagata, S., Sabaa, A. T., Grenfell, H. R., van Kerckhoven, L., Johnson, K., and Thomas, E.: The Last Global Extinction (Mid-Pleistocene) of Deep-Sea Benthic Foraminifera (Chrysalogoniidae, Ellipsoidinidae, Glandulonodosariidae, Plectofrondiculariidae, Pleurostomellidae, Stilostomellidae), Their Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic History and Taxonomy, Vol. 43, Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research Special Publication, p. 408, ISSN 0070-2242, 2012.

Herguera, J. C.: Last glacial paleoproductivity patterns in the eastern equatorial Pacific: benthic foraminifera records, Mar. Micropaleontol., 40, 259–274, 2000.

Herguera, J. C. and Berger, W. H.: Paleoproductivity from benthic foraminifera abundance: glacial to postglacial change in the West-Equatorial Pacific, Geology, 19, 1173–1176, 1991.

Holbourn, A., Henderson, A. S., and MacLeod, N.: Atlas of Benthic Foraminifera, Natural History Museum, London, Wiley-Blackwell, 642 pp., 2013.

Ilyina, T., and Zeebe, R. E.: Detection and projection of carbonate dissolution in the water column and deep-sea sediments due to ocean acidification, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L06606, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051272, 2012.

Intxauspe-Zubiaurre, B., Martinez-Braceras, N., Payros, A., Ortiz, S., Dinares-Turell, J., and Flores, J. A.: The last Eocene hyperthermal (Chron C19r event, ∼ 41.5 Ma): chronological and paleoenvironmental insights from a continental margin (Cape Oyambre, N Spain), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 505, 198–216, 2018.

Jennions, S. M., Thomas, E., Schmidt, D. N., Lunt, D., and Ridgwell, A.: Changes in benthic ecosystems and ocean circulation in the Southeast Atlantic across Eocene Thermal Maximum 2, Paleoceanography, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015PA002821, 2015.

Jones, R. W. and Charnock, M. A.: “Morphogroups” of agglutinated foraminifera. Their life positions and feeding habits and potential applicability in (paleo)ecological studies, Rev. Paleobiol., 4, 311–320, 1985.

Jorissen, F. J., Stigter, H. C., and Widmark, J. G. V.: A conceptual model explaining benthic foraminiferal microhabitats, Mar. Micropaleontol., 26, 3–15, 1995.

Jorissen, F. J., Fontanier, C., and Thomas, E.: Chapter seven, Paleoceanographical proxies based on deep-sea benthic foraminiferal assemblage characteristics, Dev. Mar. Geol., 1, 263–325, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-5480(07)01012-3, 2007.

Katz, M. E., Katz, D. R., Wright, J. D., Miller, K. G., Pak, D. K. Shackleton, N. J., and Thomas, E.: Early Cenozoic benthic foraminiferal isotopes: Species reliability and interspecies correction factors, Paleoceanography, 18, 1024, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002PA000798, 2003, 2003.

Kaminski, M. A. and Gradstein, F. M.: Cenozoic cosmopolitan deep-water agglutinated foraminifera, Grzybowski Found. Spec. Publ., 10, 1–547, 2005.

Leon-Rodriguez, L. and Dickens, G. R.: Constraints on ocean acidification associated with rapid and massive carbon injections: the early Paleogene record at ocean drilling program site 1215, equatorial Pacific Ocean, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 298, 409–420, 2010.

Loeblich Jr., A. R. and Tappan, H.: Foraminiferal Genera and their Classification, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, 970 pp., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-5760-3, 1987.

Lyle, M., Lyle, A. O., Backman, J., and Tripati, A. K.: Biogenic sedimentation in the Eocene equatorial pacific – the stuttering greenhouse and Eocene carbonate compensation depth, edited by: Wilson, P. A., Lyle, M., and Firth, J. V., Proc. Ocean Drilling Prog. Sci. Results 199, 1–35, 2005.

Meunier, M. and Danelian, T.: Astronomical calibration of late middle Eocene radiolarian bioevents from ODP Site 1260 (equatorial Atlantic, Leg 207) and refinement of the global tropical radiolarian biozonation, J. Micropalaeontol., 41, 1–27, https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-41-1-2022, 2022.

Moebius, I., Friedrich, O., and Scher, H. D.: Changes in Southern Ocean bottom water environments associated with the Middle Eocene Climatic Optimum (MECO), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 405, 16–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.04.004, 2014.

Müller-Merz, E. and Oberhänsli, H.: Eocene bathyal and abyssal benthic foraminifera from a South Atlantic transect at 20–30° S, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 83, 117–171, https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(91)90078-6, 1991.

Murray, J. W.: Ecology and Paleoecology of Benthic Foraminifera, Longman, Harlow, 397 pp., https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315846101, 1991.

Nguyen, T. M. P., Petrizzo, M. R., and Speijer, R. P.: Experimental dissolution of a fossil foraminiferal assemblage (Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, Dababiya, Egypt): Implications for paleoenvironmental reconstructions, Mar. Micropaleontol., 73, 241–258, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2009.10.005, 2009.

Palmer, H. M., Hill, T. M., Roopnarine, P. D., Myhre, S. E., Reyes, K. R., and Donnenfield, J. T.: Southern California margin benthic foraminiferal assemblages record recent centennial-scale changes in oxygen minimum zone, Biogeosciences, 17, 2923–2937, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-2923-2020, 2020.

Pearson, P. N.: Increased atmospheric CO2 during the middle Eocene, Science, 330, 763–764, 2010.

Peñalver-Clavel, I., Agnini, C., Westerhold, T., Cramwinckel, M. J., Dallanave, E., Bhattacharya, J., Sutherland, R., and Alegret, L.: Integrated record of the Late Lutetian Thermal Maximum at IODP site U1508, Tasman Sea: The deep-sea response, Mar. Micropaleontol., 191, 102390, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2024.102390, 2024.

Peñalver-Clavel, I., Batenburg, S. J., Sutherland, R., Dallanave, E., Dickens, G. R., Westerhold, T., Agnini, C., and Alegret, L.: Intensified bottom water formation in the southwest Pacific during the early Eocene greenhouse – insights from neodymium isotopes, Geology, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1130/G52974.1, 2025a.

Peñalver-Clavel, I., Westerhold, T., and Alegret, L.: Supplementary Information: Deep-sea benthic foraminiferal response to the Late Lutetian Thermal Maximum at Demerara Rise (ODP Site 1260, equatorial western Atlantic), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17599663, 2025b.

Pflum, C. E. and Frerichs, W. E.: Gulf of Mexico Deep-water Foraminifers, in: Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research (Volume 14), edited by: Sliter, W. V., Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research, ISBN 9781970168082, 1976.

Pineau, E., Donnadieu, Y., Maffre, P., Lique, C., Huck, T., Gramoullé, A., and Ladant, J.-B.: A model-based study of the emergence of North Atlantic deep water during the Cenozoic: A tale of geological and climatic forcings, Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 40, e2024PA005020, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024PA005020, 2025.

Putra, P. S., Yulianto, E., and Nugroho, S. H.: Distribution patterns of foraminifera in paleotsunami layers: A review, Natural Hazards Research, 3, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nhres.2022.12.004, 2023.

Renaudie, J., Danelian, T., Saint Martin, S., Le Callonnec, L., and Tribovillard, N.: Siliceous phytoplankton response to a Middle Eocene warming event recorded in the tropical Atlantic (Demerara Rise, ODP Site 1260A), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 286, 121–134, 2010.

Rivero-Cuesta, L., Westerhold, T., Agnini, C., Dallanave, E., Wilkens, R.H., and Alegret, L.: Paleoenvironmental changes at ODP Site 702 (South Atlantic): Anatomy of the Middle Eocene Climatic Optimum, Paleoceanogr. and Paleoclimatol., 34, 2047–2066, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019PA003806, 2019.