the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Agglutinated foraminifera from the Turonian–Coniacian boundary interval in Europe – paleoenvironmental remarks and stratigraphy

Richard M. Besen

Kathleen Schindler

Andrew S. Gale

Ulrich Struck

Agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages of the Turonian–Coniacian from the GSSP (Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point) of Salzgitter–Salder (Subhercynian Cretaceous Basin, Germany) and other sections, including Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm (Münsterland Cretaceous Basin, Germany) and the Dover–Langdon Stairs (Anglo-Paris Basin, England), from the temperate European shelf realm were studied in order to collect additional stratigraphic and paleoenvironmental information. Stable carbon isotopes were measured for the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section to establish a reliable stratigraphic correlation with other sections. Highly diverse agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages were obtained from sections in the German basins, whereas the fauna from Dover is less rich in taxa and less abundant. In the German basinal sections, a morphogroup analysis of agglutinated foraminifera and the calculated diversities imply normal marine settings and oligotrophic to mesotrophic bottom-water conditions. Furthermore, acmes of agglutinated foraminifera correlate between different sections and can be used for paleoenvironmental analysis. Three acmes of the species Ammolagena contorta are recorded for the Turonian–Coniacian (perplexus to lower striatoconcentricus zones, lower scupini Zone, and hannovrensis Zone) and likely imply a shift to more oligotrophic bottom-water conditions. In the upper scupini Zone below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary, an acme of Bulbobaculites problematicus likely indicates enhanced nutrient availability.

In general, agglutinated foraminiferal morphogroups display a gradual shift from Turonian oligotrophic environments towards more mesotrophic conditions in the latest Turonian and Coniacian.

- Article

(9870 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(417 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

In the search for a GSSP (Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point) for the base of the Coniacian stage and subsequent proposal of the Salzgitter–Salder quarry as a potential candidate defined by the first occurrence of the inoceramid bivalve Cremnoceramus deformis erectus (Wood et al., 1984), the quarry section was the subject of intense studies and discussions (e.g. Voigt and Hilbrecht, 1997; Wood and Ernst, 1998; Walaszczyk and Cobban, 1999, 2000; Walaszczyk and Wood, 1998; Sikora et al., 2004; Wiese et al., 2004; Walaszczyk et al., 2010; Wiese et al., 2015). Recent studies have clarified all stratigraphic issues of the Salzgitter–Salder quarry, approved its status as the GSSP for the Turonian–Coniacian boundary, and added biostratigraphical and paleoecological data (e.g. Čech and Uličný, 2020; Voigt et al., 2020; Jarvis et al., 2021; Walaszczyk et al., 2022). While records of planktonic organisms including foraminifera (Sikora et al., 2004; Walaszczyk et al., 2010), palynomorphs, and calcareous nannofossils (Jarvis et al., 2021) are documented, little information on benthic microfossils and only on calcareous foraminifera has been published (Walaszczyk et al., 2022).

Several studies have shown the diverse abundances of agglutinated foraminifera in Turonian–Coniacian calcareous deposits (e.g. Kuhnt, 1990; Kaminski et al., 2011; Besen et al., 2021, 2022a, b), while the utility of these forms in assemblages originally dominated by calcareous foraminifera as a proxy for paleoenvironmental reconstruction was the subject of studies on recent and past deposits (e.g. Murray and Alve, 1994, 1999a, b, 2011; Murray et al., 2003). Even with the existence of calcareous benthic foraminiferal assemblages, highly diverse agglutinated foraminifera are present and can be used to reconstruct past environments.

In this study, we present results of the records of agglutinated foraminifera from the Turonian–Coniacian boundary interval of Salzgitter–Salder and other European sections as well as their implications for biostratigraphy and paleoecology. Additional carbon isotope data for the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section (Münsterland Cretaceous Basin, Germany) enable a precise stratigraphic correlation of micropaleontological information.

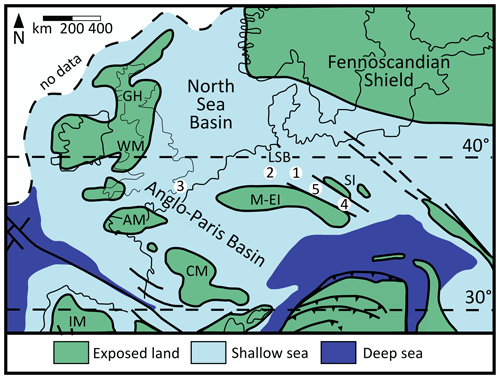

The study area (Fig. 1) is characterised by the former temperate (“boreal”) mid-Cretaceous shallow shelf sea, which spanned northern to middle Europe north of the Central Massif, Mid-European Island, and Sudetic islands; east of the Armorican and Welsh Massif; south of the Fennoscandian Shield landmass; and west of the Danish–Polish Trough (Skelton, 2003; Voigt et al., 2008; Janetschke et al., 2015).

Figure 1Paleogeographical map of Europe during the mid-Cretaceous, modified after Philip and Floquet (2000); locations: (1) Salzgitter–Salder, (2) Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, (3) Dover–Langdon Stairs, (4) Bch-1 – Běchary, (5) Graupa – Graupa. Abbreviations: AM – Amorican Massif, CM – Central Massif, GH – Grampian High, IM – Iberian Massif, M–EI – Mid-European Island, SI – Sudetic islands, WM – Welsh Massif, LSB – Lower Saxony Basin.

2.1 Salzgitter–Salder, Niedersachsen, Germany

The strata of the Salzgitter–Salder quarry are part of the Salzgitter Anticline with WGS84 coordinates 52.124294∘ N and 10.329261∘ E in the Subhercynian Cretaceous Basin (Fig. 1). The section contains around 220 m of extended middle Turonian to lower Coniacian marl–limestones of the Söhlde, Salder, and Erwitte formations (see Sect. 4.1). The Söhlde Formation is expressed by thin-bedded marl–limestone rhythmites in the lower 6.50 m (−87.5 to −94 m) of the studied interval. Highly lithified limestones of the Salder Formation follow (−87.5 to 20 m). Above, marl–limestone alternations of the Erwitte Formation are exposed (20 to 99 m). As the ratified GSSP section for the Turonian–Coniacian boundary, detailed stratigraphic information is provided by several authors (e.g. Wood et al., 1984; Voigt and Hilbrecht, 1997; Wood and Ernst, 1998; Sikora et al., 2004; Walaszczyk and Wood, 1998; Walaszczyk et al., 2010; Voigt et al., 2020; Jarvis et al., 2021; Walaszczyk et al., 2022).

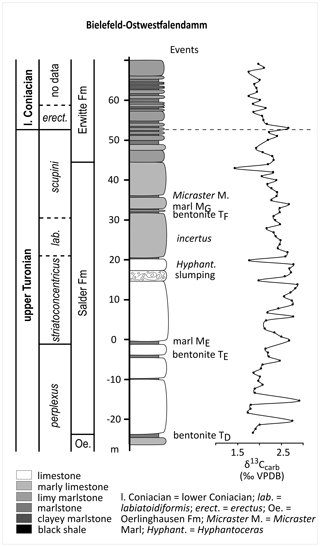

2.2 Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany

The Ostwestfalendamm section in Bielefeld is a roadcut of the B61 through the Osning in the northern Teutoburger Wald. The section lies at the north-eastern edge of the Münsterland Cretaceous Basin (Fig. 1) with WGS84 coordinates 52.004188∘ N and 8.501601∘ E. The exposed lithology comprises upper Cenomanian to lower Coniacian marlstones to limestones. The lithological interval covered in this study includes a 67.5 m thick succession of highly lithified limestones of the Salder Formation (−22 to 44.5 m) and 25.5 m of marlstone to limestone alternations of the Erwitte Formation (44.5 to 70 m) of late Turonian to early Coniacian age (Fig. 2). The section was documented in detail regarding its lithology, event stratigraphy, and biostratigraphy based on inoceramid bivalves, ammonites, planktic foraminifera, and calcareous nannofossils by Appfel (1993) and Wray et al. (1995). Good comparison potential is given with the well-studied sections Oerlinghausen and Halle–Hesseltal (Wray et al., 1995; Voigt et al., 2007; Kaplan, 2011).

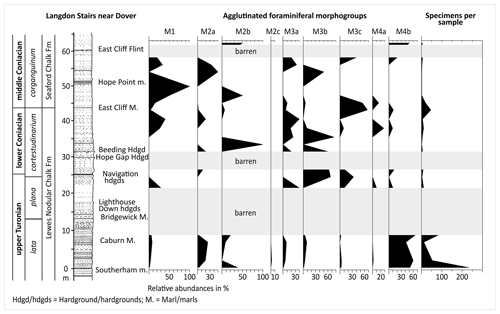

2.3 Dover–Langdon Stairs, Kent, England

The Langdon Stairs pathway section east of the Dover port is accessible over a zigzag path to the sea along the cliff. Its Cretaceous strata were deposited in the Anglo-Paris Basin. The WGS84 coordinates of the section are 51.133829∘ N and 1.351213∘ E. The stratigraphic succession covered in this study at the Langdon Stairs is expressed by an upper Turonian to middle Coniacian ca. 66 m thick chalk succession with intercalated cherts and hardgrounds belonging to the Lewes Nodular Chalk Formation (0 to 44 m) and the Seaford Chalk Formation (44 to 65 m). The studied interval stretches from the Southerham marls at the base to shortly above the East Cliff Flint (see Sect. 4.1). As a reference section for the English Chalk a detailed stratigraphic framework is provided by many authors (e.g. Jenkyns et al., 1994; Jarvis et al., 2006; Lees, 2008).

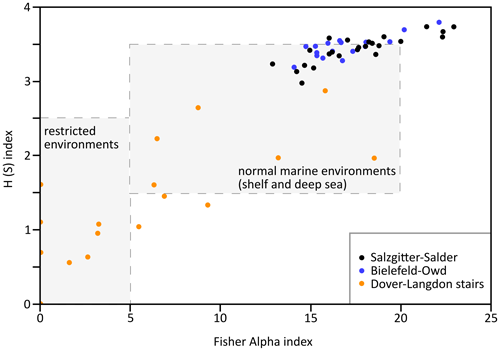

The section Langdon Stairs was sampled at 2 m intervals, while at the sections Ostwestfalendamm and Salzgitter–Salder samples were taken every 5 to 10 m because of their higher sedimentation rates. Preferably, limestones were chosen for sampling. After chemical treatment with formic acid following Besen et al. (2022b) on around 100 g for each sample, the residues were washed, dried, and studied for the examination and determination of agglutinated foraminifera. If needed, the samples were split with a micro-splitter. This study follows the taxonomic works of Loeblich and Tappan (1987), Frieg and Price (1982), Frieg and Kemper (1989), Kaminski and Gradstein (2005), Kaminski et al. (2011), and Setoyama et al. (2017). In total, 509 specimens of 44 different taxa in 25 samples from the Langdon Stairs, 5937 specimens of 75 different taxa in 17 samples from the Ostwestfalendamm section, and 7813 specimens of 87 taxa in 24 samples from the Salzgitter–Salder section were determined on the species level. At least 300 specimens were counted per sample, excluding all samples from the Langdon Stairs section due to low abundances of specimens per gram. All tubular specimen counts were divided by a factor of 5 to limit the statistical impact of fragmented specimens (Bubík, 2019). The Fisher alpha index (Fisher et al., 1943) and the H(S) index (Shannon, 1948) were calculated to show fluctuations of foraminiferal diversity. Assemblages with lower Fisher alpha and/or H(S) indices show lower diversity, and vice versa. Both indices were plotted against each other to make assumptions about the depositional environment following observations on modern and past assemblages (Murray, 2006; Nagy et al., 2011, 2013; Hjálmarsdóttir et al., 2022). A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the PAST programme package (Hammer et al., 2001) to attribute paleoenvironmental factors to relative abundances of certain taxa. For this analysis, taxa with low occurrences (≤10 specimens) or only a single appearance in the samples were excluded. First and last occurrences (FOs and LOs) are documented and correlated between the studied sections.

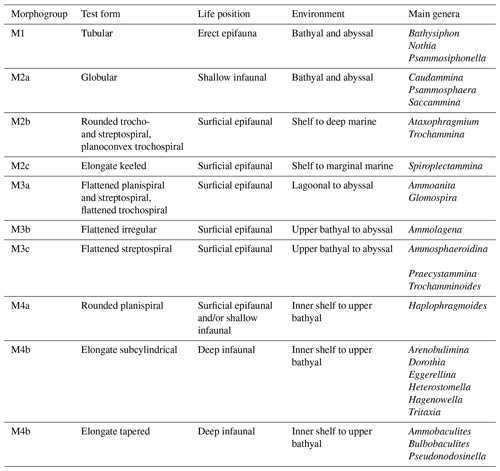

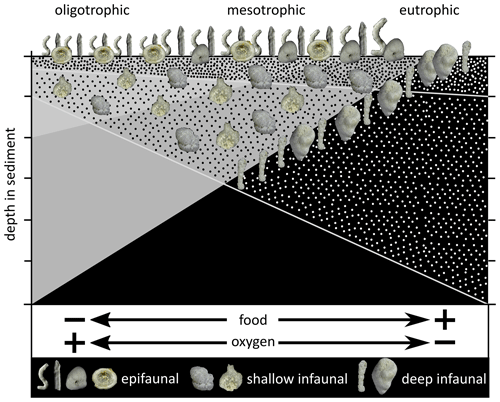

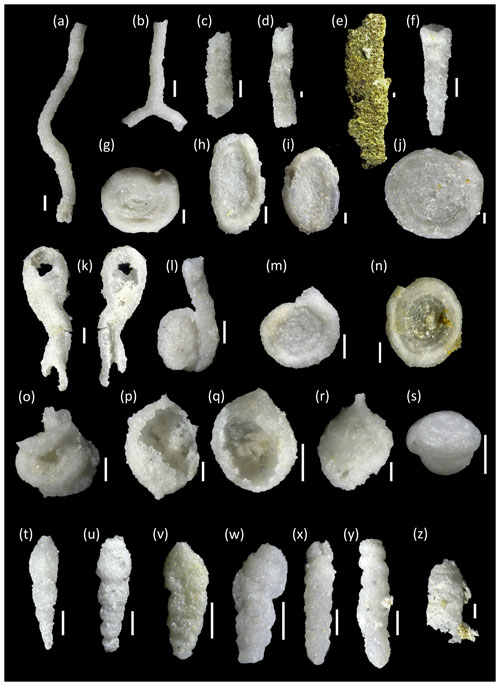

With morphogroups of different agglutinated foraminifera (Table 1), which are dependent on their living and feeding strategies, environmental changes can be reconstructed based on the scheme of Jones and Charnock (1985). This model was subsequently modified and improved by Bąk et al. (1997), Peryt et al. (1997, 2004), van den Akker et al. (2000), and Murray et al. (2011). The scheme presented here (Table 1) was adapted for Cretaceous assemblages by Frenzel (2000), Cetean et al. (2011a), and Setoyama et al. (2017). High relative abundances of at least 10 % of the fauna, expressed as acmes or foraminiferal bioevents of agglutinated foraminiferal species, were documented. All displayed photographs of agglutinated foraminifera were processed on a Keyence VHX-1000 digital microscope multi-scan at the Freie Universität Berlin (paleontology section).

Table 1Agglutinated foraminiferal morphogroups, morphotypes and test forms, and life environments modified after Frenzel (2000), Cetean et al. (2011a), and Setoyama et al. (2017) correlated with the main genera treated within this study.

The Ostwestfalendamm section was sampled in a 1 m interval for bulk-carbonate carbon isotope measurements. Those were applied by using a GasBench II linked to a Thermo Fischer Scientific DeltaV isotope ratio mass spectrometer at the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin. All given values are displayed in permil (‰) versus VPDB (Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite).

4.1 Stable carbon isotopes

Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm

The upper Turonian to lower Coniacian of the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section yields δ13C values between 1.43 ‰ and 2.87 ‰ (Fig. 2). From the bentonite TD up to strata around the Hyphantoceras Event values continuously increase from 1.85 ‰ to 2.87 ‰. A distinct positive peak is visible at the Hyphantoceras Event. Up-section measured δ13C values decrease with several smaller minima and maxima to 1.9 ‰ shortly below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary. Another significant maximum shortly above the Turonian–Coniacian boundary contains δ13C values of up to 2.66 ‰.

4.2 Agglutinated foraminifera

4.2.1 Salzgitter–Salder

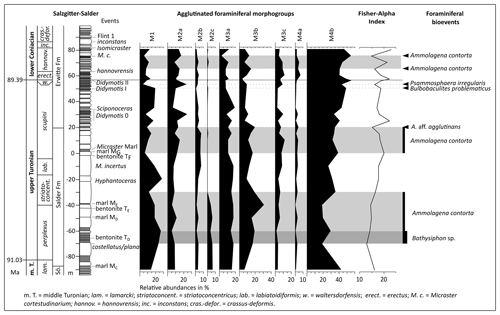

Diverse agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages are recorded at the Salzgitter–Salder quarry section with 6.8 to 25 specimens g−1 with a Fisher alpha index between 14.7 and 22.9 (Fig. 3). Ammobaculites aff. agglutinans, Ammolagena contorta, Arenobulimina preslii, Bathysiphon sp., Bulbobaculites problematicus, Eggerellina brevis, and Psammosphaera irregularis are the most common taxa. While the relative abundance of morphogroup M4b ranges between 33.5 and 55.1, morphogroups M1, M2a, M3a, and M3b do not exceed 20 % relative abundance, and morphogroups M2b, M3c, and M4a show relative abundances lower than 10 % (Fig. 3). An interval of enhanced relative abundances of Ammolagena contorta appears from the bentonite TF to 20 m above, ending with an acme of Ammobaculites aff. agglutinans. Above the Didymotis Event I, an acme of Bulbobaculites problematicus appears, shortly followed by enhanced abundances of Psammosphaera irregularis. Shortly above the C. w. hannovrensis Event and at the M. cortestudinarium Event, acmes of Ammolagena contorta occur (Fig. 3).

Figure 3Chrono-, litho-, and biostratigraphy of the Turonian–Coniacian of the Salzgitter–Salder section with agglutinated foraminiferal morphogroups, Fisher alpha index, and foraminiferal events (acmes) indicated by bars and arrows. For log legend, see Fig. 2; log redrawn after Niebuhr et al. (2007; fig. 16); events are from Wood et al. (1984), Niebuhr et al. (2007), and Walaszczyk et al. (2010), and biostratigraphy is from Voigt et al. (2020).

In the Turonian of the Salzgitter–Salder quarry Uvigerinammina jankoi (Plate 1) has its FO shortly below the marl MD in the I. perplexus Zone. About 3 m above the Turonian–Coniacian boundary, the FO of Heterostomella carinata (Plate 1) is recorded. In overlying Coniacian strata, the FOs of Spiroplectammina sp. (Plate 1) and Dorothia conula are recorded about 6 m and 1 m below the M. cortestudinarium Event in the C. w. hannovrensis Zone, respectively (see Sect. 5.2).

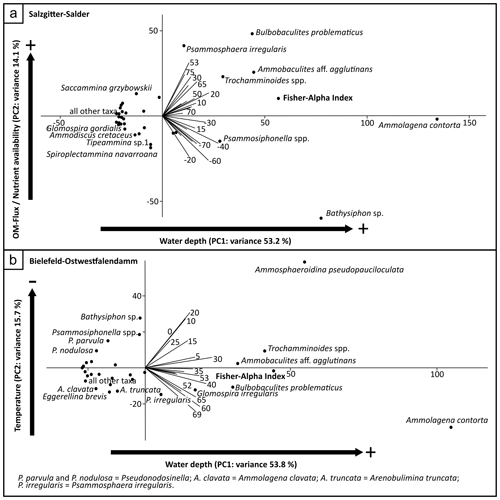

The PCA performed on the dataset from the Salzgitter–Salder quarry showed that PC1 and PC2 are reasonable for 53.2 % and 14.1 % of the variance, respectively (see Sect. 6).

4.2.2 Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm

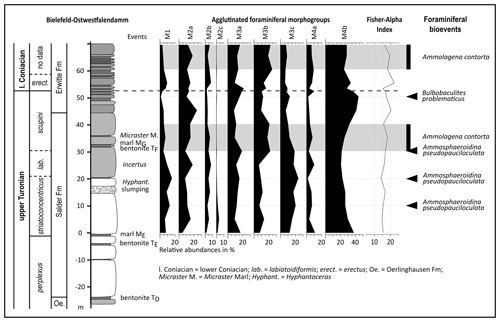

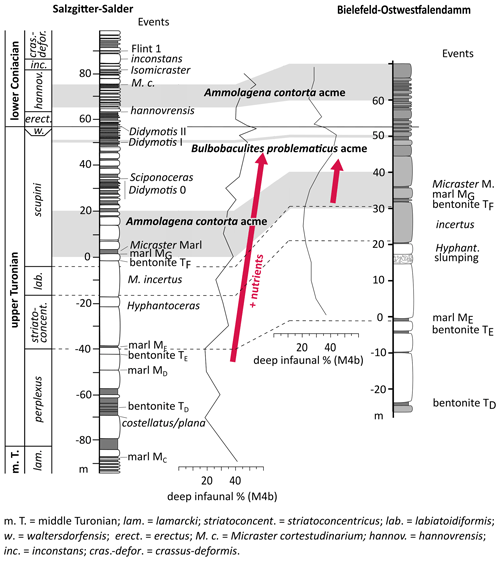

The upper Turonian to lower Coniacian strata of the Ostwestfalendamm section at Bielefeld yield diverse agglutinated foraminiferal faunas with 3.3 to 8.7 specimens g−1 (Fig. 4). The Fisher alpha index fluctuates between 14.1 above the Hyphantoceras Event and 22.2 shortly above the Turonian–Coniacian boundary. Commonly occurring taxa are Ammobaculites aff. agglutinans, Ammolagena contorta, Ammosphaeroidina pseudopauciloculata, Bulbobaculites problematicus, Glomospira gordialis, and Psammosphaera irregularis (Plate 1). The infaunal morphogroup M4b as the main group ranges between 20 % and 43 % of the foraminiferal fauna in the Ostwestfalendamm section with a maximum abundance shortly below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary. Other morphogroups do not exceed 20 % relative abundances (Fig. 4). Ammosphaeroidina pseudopauciloculata appears in three acmes in the upper Turonian: 10 m above the marl ME, at the Hyphantoceras Event, and shortly below the bentonite TF. Ammolagena contorta has enhanced abundances from shortly below bentonite TF to about 3 m above the Micraster Marl and between 8 m above the Turonian–Coniacian boundary and the top of the studied section. Shortly below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary, Bulbobaculites problematicus appears in high numbers (Fig. 4).

Figure 4Chrono-, litho-, and biostratigraphy of the Turonian–Coniacian of the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section with agglutinated foraminiferal morphogroups, Fisher alpha index, and foraminiferal events (acmes) indicated by bars and arrows. For log legend, see Fig. 2; log redrawn after Appfel (1993).

About 5 m above the marl ME, Uvigerinammina jankoi has its FO at Bielefeld. The FO of Heterostomella carinata was observed at the top of the section about 13 m above the Turonian–Coniacian boundary. Dorothia conula and Spiroplectammina spp. were not recorded in the Ostwestfalendamm section (see Sect. 5.2).

PC1 of the performed PCA on the dataset from the Ostwestfalendamm section explains 53.8 % of the variance, while PC2 relates to 15.7 % (see Sect. 6).

4.2.3 Dover–Langdon Stairs

Samples of the Langdon Stairs pathway section yield only low-abundance agglutinated foraminiferal faunas. In most of the samples, the specimen per gram ratio does not exceed 0.5 specimens g−1 (Fig. 5). Intervals around the Bridgewick marls and Lighthouse Down hardgrounds, below the Hope Gap Hardground, and at the East Cliff Flint are barren of agglutinated foraminifera. Only in one sample shortly above the Southerham marls was rich foraminiferal fauna documented (Fig. 5). While samples in the basal part of the studied stratigraphical interval, between Southerham marls and Caburn Marl, are mainly dominated by the occurrence of infaunal foraminifera of the morphogroup M4b, such as Ataxophragmium depressum, Eggerellina brevis, and Hagenowella elevata, samples up-section are expressed by epifaunal dominated foraminifer assemblages, with taxa such as Ammoanita sp., Ammolagena contorta, and Bathysiphon sp. (Fig. 5 and Plate 1). Due to the incomplete foraminiferal record at Dover, no FOs or LOs could be identified. One specimen of Uvigerinammina jankoi was recorded at the base of Langdon Stairs section in the Southerham marls.

5.1 Carbon isotope stratigraphy

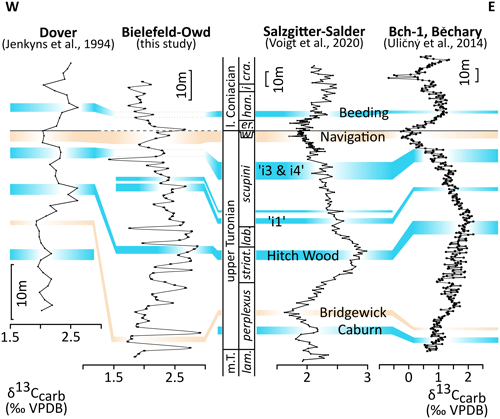

The measured carbon isotope pattern of Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm (Fig. 2) was studied for its carbon isotope events (CIEs) and correlated with reference sections in Europe: Salzgitter–Salder (Voigt and Hilbrecht, 1997; Walaszczyk et al., 2010; Voigt et al., 2020), Dover–Langdon stairs (Jenkyns et al., 1994; Jarvis et al., 2006), and the Bch-1 core (Uličný et al., 2014; Jarvis et al., 2015; Olde et al., 2015) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6Carbon isotope correlation between Dover–Langdon Stairs (Jenkyns et al., 1994), Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm (this study), Salzgitter–Salder (Voigt and Hilbrecht, 1997; Voigt et al., 2020), and Bch-1 at Běchary (Uličný et al., 2014). Carbon isotope events are from Voigt et al. (2020), and chrono- and biostratigraphy (see Fig. 3) are from Voigt et al. (2020) and Walaszczyk et al. (2022). Blue: positive carbon isotope events, orange: negative carbon isotope events. Abbreviations: Bielefeld–Owd – Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm.

The Bridgewick CIE, which is expressed as a distinct minimum at Salzgitter–Salder (Walaszczyk et al., 2010) and Dover (Jarvis et al., 2006) (Fig. 6), most likely occurs about 10 m above the bentonite TD at Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm.

Indicated by the most pronounced maximum in the interval, the Hitchwood CIE is recognised in all sections (Fig. 6). While this CIE appears at the Hitch Wood Hardground at Dover (Gale, 1996; Jarvis et al., 2006), it is synchronous with the Hyphantoceras Event in Germany (Walaszczyk et al., 2010; Richardt and Wilmsen, 2012). At Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm it appears about 5 m below the Hyphantoceras Event (Figs. 2 and 6). This offset may be explained by intense redeposition of strata at this stratigraphical interval in the eastern Münsterland Cretaceous Basin. In the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin (Bch-1 core), the CIE is recorded shortly above the Hyphantoceras Event.

Above, some smaller positive peaks are recognisable in the carbon isotope records (Fig. 6). The peak i1 after Jarvis et al. (2006) and Peak+2, which correlates with the Micraster Event in Germany (Wiese, 1999), are well correlatable between the German sections (Salzgitter–Salder and Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm) (Fig. 6). The minor peaks i3 and i4 occurring at the Didymotis Event I and the Sciponoceras Event at Salzgitter–Salder likely correlate with pronounced positive peaks which occur several metres below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary at Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm (Fig. 6). In the southern Münsterland Cretaceous Basin, these peaks are not visible due to an extensive hiatus in the scupini Zone (Richardt and Wilmsen, 2012).

The Navigation CIE, which is a complemental criterion to define the Turonian–Coniacian boundary, correlates well between all sections (Fig. 6). This CIE is described in detail at Salzgitter–Salder, Dover, and the Bch-1 core (Jarvis et al., 2006; Uličný et al., 2014; Voigt et al., 2020; Walaszczyk et al., 2022). At Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, the Navigation CIE is well developed (Fig. 2) and its upper extent fits the reported first occurrence of Cremnoceramus rotundatus by Appfel (1993). C. rotundatus is seen to be a junior synonym of C. deformis erectus (see Walaszczyk and Cobban, 1999, 2000; Walaszczyk and Wood, 1998). A directly following pronounced positive peak in lower Coniacian strata at Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm (Fig. 2) was not recorded in the Dover, Salzgitter–Salder, and Bch-1 core sections or in the southern Münsterland Basin (Richardt and Wilmsen, 2012).

Coniacian CIEs such as the Beeding CIE are not reliably determinable in the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section (Figs. 2 and 6).

5.2 Agglutinated foraminiferal biostratigraphy

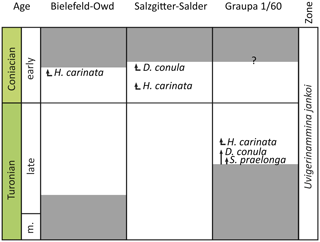

All sections can be assigned to the Uvigerinammina jankoi biozone (Fig. 7). While this species is already abundant from the base in the Langdon Stairs section, it first appears in the I. perplexus Zone at Bielefeld and in the M. labiatoidiformis Zone at Salzgitter–Salder. However, U. jankoi was observed to appear earlier in the middle Turonian in nearby sections: in Oerlinghausen (own observations by RMB) at about 15 km distance from the Ostwestfalendamm section and in Söhlde (Besen et al., 2021) at about 10 km distance from the Salzgitter–Salder section. The absence of this taxa in the basal metres of both studied sections is probably induced by the generally rare occurrence of U. jankoi in the German basins.

Figure 7Recorded Turonian to Coniacian FOs (first occurrences) of agglutinated foraminiferal taxa and an agglutinated foraminiferal zonation from the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section (this study), the Salzgitter–Salder section (this study), and the Graupa core (Besen et al., 2022a). Grey – not studied or exposed. Abbreviations: m. – middle, D. conula – Dorothia conula, G. carinata – Heterostomella carinata, S. praelonga – Spiroplectammina praelonga.

Other typical late Turonian agglutinated foraminifera such as Dorothia conula, Heterostomella carinata, and Spiroplectammina sp. occur in the studied sections, except in the Langdon Stairs section. D. conula first occurs in the lower Coniacian at Salzgitter (Fig. 7). This species is also documented from the upper Cenomanian (Elicki et al., 2020) and upper Turonian of Saxony (Besen et al., 2022a), whereas D. conula from the Cenomanian more likely represents Plectina cenomana because it lacks nearly parallel sides and increasing growth of chambers. G. carinata and S. praelonga firstly occur in the lower Coniacian in the Salzgitter–Salder section (Fig. 7). G. carinata is observed 13 m above the Turonian–Coniacian boundary at Bielefeld, while S. praelonga is absent (Fig. 7). Both taxa are reported from the upper Turonian of Saxony (Besen et al., 2022a). The stepwise appearance of these species possibly reflects a westward migration pattern from the central Tethyan realm during the transgressive phase in the late Turonian.

6.1 Salzgitter–Salder

Agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages of the middle Turonian to lower Coniacian from the Salzgitter–Salder quarry are composed of tubular, epifaunal, and attached foraminifera (M1–M4a) with relative abundance usually below 20 %. Relative abundances of infaunal foraminifera (M4b) – including typical shelf related taxa – range between 20 % and 55 % (Fig. 3). Thus, recorded assemblages can be assigned to the mid-latitude shelf biofacies proposed by Besen et al. (2021). The consistent occurrence of all morphogroups and the recorded diversities (Fig. 8) indicate a normal marine shelf environment considering observations of modern, Mesozoic, and Paleozoic shelf assemblages (Murray, 2006; Nagy et al., 2011, 2013; Hjálmarsdóttir et al., 2022). The presence of tubular forms in all samples could indicate the existence of a weak bottom current following assumptions by Murray et al. (2011).

Figure 8Sample plots of Fisher alpha vs. H (S) indices of all samples from Salzgitter–Salder (black), Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm (blue), and Dover–Langdon Stairs (orange); common indices for restricted and normal marine (shelf and deep sea) environments are indicated as grey boxes. Note: indices can plot outside the boxes; for a detailed explanation see Sect. 3 or Murray (2006).

Figure 9TROX model (redrawn and modified after Jorissen et al., 1995; Van der Zwaan et al., 1999; Setoyama et al., 2017). Shelf-associated deep infaunal morphotypes are added, reflecting the mid-latitude shelf biofacies.

Applying the TROX model after Jorissen et al. (1995), Van der Zwaan et al. (1999), and Setoyama et al. (2017) (Fig. 9), mesotrophic to slightly oligotrophic bottom-water conditions during the middle Turonian to early Coniacian are likely. Upper Turonian strata, especially belonging to the Salder Formation, at Salzgitter yield comparably lower relative abundances of infaunal foraminifera (Fig. 3), indicating more oligotrophic bottom-water conditions. This is in accordance with trophic conditions postulated for the upper water layers during the Turonian nutrient crisis (Wiese et al., 2015; 2017) and observations of the performed PCA (Fig. 10), which indicates the lowest organic matter influx from the costellatus/plana marl up to the M. incertus Event (−70 to −10 m section). Agglutinated foraminiferal taxa favoured by these conditions are Bathysiphon sp., Psammosiphonella spp., Spiroplectammina navarroana, and Tipeammina sp. 1 (see Plate 1). A decline in diversity in this interval as observed for planktic assemblages is not visible in the agglutinated foraminiferal record. The possible adaption of many DWAF (deep-water agglutinated foraminifera) taxa to oligotrophic conditions in deeper habitats (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005) limited the impact on agglutinated foraminiferal diversity during a shift to oligotrophic conditions.

Figure 10Principal component analyses based on agglutinated foraminiferal abundances and the Fisher alpha indices for the following: (a) Salzgitter–Salder, variance – PC1 (water depth) 53.2, PC2 (OM–flux–nutrient availability) 14.1; (b) Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, variance – PC1 (water depth) 53.8, PC2 (temperature) 15.7.

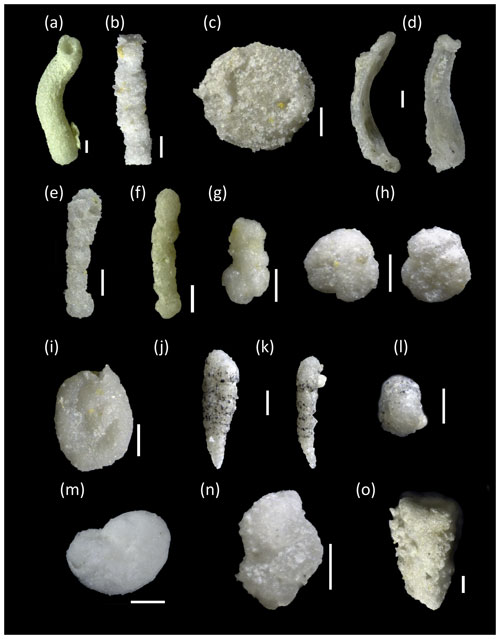

Plate 1Middle Turonian to lower Coniacian agglutinated foraminifera from northern Europe used for paleoenvironmental interpretations; scale bars are 100 µm. (a) Bathysiphon sp., Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 69.00 m. (b) Psammosiphonella sp., Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (c) Psammosphaera irregularis, Salzgitter–Salder, 25.00 m. (d) Ammolagena contorta, Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 10.00 m. (e) Ammobaculites agglutinans, Salzgitter–Salder, 20.00 m. (f) Bulbobaculites problematicus, Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 5.00 m. (g) Bulbobaculites problematicus, Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 0.00 m. (h) Ammosphaeroidina pseudopauciloculata, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m, left: dorsal view, right: ventral view. (i) Glomospira gordialis, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (j–l) Spiroplectammina navarroana, Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 5.00 m, (k) side view, (l) apertural view. (m) Ammoanita sp., Dover–Langdon stairs, 43.50 m. (n) Uvigerinammina jankoi, Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 5.00 m. (o) Heterostomella carinata, Salzgitter–Salder, −10.00 m.

A relative abundance maximum of the attached morphogroup (M3b) at the marl ME (Fig. 3) likely correlates with conditions during maximum flooding supported by the PCA (Fig. 10), indicating a relatively higher water depth (−40 to −30 m section). Slower carbonate sedimentation rates during maximum flooding due to a breakdown of bioproductivity in the upper water layers shown by Wiese et al. (2015) likely favoured the bloom of incrusting agglutinated foraminiferal taxa, e.g. Ammolagena contorta. A similar acme of A. contorta (Plate 1) appears at the Micraster Marl (Fig. 3), which is also related to maximum flooding (Wiese et al., 2004, 2015), and overlying strata. A relatively higher water depth at the base of the Erwitte Formation (20 m section) is indicated by the PCA (Fig. 10), which fits observations made by Wiese et al. (2004). In addition, A. contorta, Ammobaculites aff. agglutinans, Bathysiphon sp., and Bulbobaculites problematicus (Plate 1) likely favour deeper water depths. Conditions of the relatively lower water depth indicated by the PCA (Fig. 10) are located below the marl MC (−90 m section), shortly below the Sciponoceras Event (35 m section), at the Turonian–Coniacian boundary (56 to 57.2 m section), and in the hannovrensis Zone (70 m section).

A general increase in relative abundance of infaunal taxa (M4b) during the late Turonian until the Turonian–Coniacian boundary (Fig. 3) likely indicates a smooth transition to more mesotrophic bottom-water conditions in the early Coniacian. PCA indicates the highest organic matter flux at this interval with taxa occurring such as A. aff. agglutinans, B. problematicus, Psammosphaera irregularis (Plate 1), and Trochamminoides spp. Features indicating higher nutrient availability are observed in planktic calcareous nannofossil assemblages at Salzgitter–Salder and other European sections (Jarvis et al., 2021). Jarvis et al. (2021) even postulate a regional paleoproductivity pulse caused by upwelling in the lower hannovrensis Zone contemporaneous with the Beeding Event. Peaks of relative abundances of infaunal agglutinated foraminiferal morphogroups at Salzgitter–Salder (Fig. 3) – indicating higher food availability – occur earlier shortly below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary and later in the higher hannovrensis Zone contemporaneous with the M. cortestudinarium Event. The planktic paleoproductivity pulse interpreted by Jarvis et al. (2021) likely did not affect the agglutinated foraminiferal fauna, and furthermore, intervals of high food availability in bottom waters were not necessarily caused by enhanced productivity in the upper water layers.

6.2 Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm

At Bielefeld, agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages can be assigned to the mid-latitude shelf biofacies. Diversity patterns indicate a normal marine shelf environment (Fig. 8). While the infaunal morphogroup (M4b) ranges 20 %–45 % for all assemblages, other morphogroups do not exceed 20 % (Fig. 4). Overall, assemblages are well comparable to those recorded at Salzgitter–Salder.

Decreasing relative abundances of M4b (Fig. 4) from shortly above marl ME (0 m section) up to the M. incertus Event (25 m section) reflect a continuous shift to more oligotrophic conditions. But, following the TROX model (Fig. 9), food supply was likely comparably low for such shelf conditions. Above, increasing relative abundances of M4b (Fig. 4) to shortly below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary (45 to 50 m section) indicate higher food availability thus more mesotrophic conditions of the bottom water. High food availability shortly below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary is also supported by an acme of Bulbobaculites problematicus (Fig. 4; see the discussion in Sect. 6.1). Above the boundary, decreasing relative abundances of infaunal foraminifera again likely refer to lower food availability.

Higher relative sea levels are likely indicated by increased abundances of Ammolagena contorta and PCA (Figs. 4 and 10). Following the PCA, sea level was likely relatively higher around the Micraster Marl (30 to 40 m section) and in the early Coniacian (60 to 69 m section).

Likely indicated by increased relative abundances of Ammosphaeroidina pseudopauciloculata, which likely prefers colder and deeper habitats (Nagy et al., 2000), and PCA (Figs. 4 and 10), the bottom-water conditions were colder from marl ME up to the M. incertus Event (0 to 25 m section). Three distinct acmes of A. pseudopauciloculata (Fig. 4) below (10 m section) and at the Hyphantoceras Event (20 m section), as well as shortly below bentonite TF (30 m section), can probably be interpreted as regional cold pulses. Maybe these indications of relatively colder environments are partly related to phase III of the Late Turonian Cooling Event proposed by Voigt and Wiese (2000) and Wiese and Voigt (2002). Relatively warmer bottom-water conditions are most likely for the early Coniacian (60 to 69 m section), as indicated by results of the PCA (Fig. 10).

6.3 Dover–Langdon Stairs

The agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages recorded in the Langdon Stairs section are, with the exception of one sample, of low diversity at the Southerham marls with only a few specimens having a few different species per sample (Fig. 5). Diverse agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages of the Southerham marls at the base of the section (Fig. 5) likely indicate well-oxygenated mesotrophic bottom-water conditions according to the TROX model (Fig. 10) established by Jorissen et al. (1995) and Van der Zwaan et al. (1999). Those compare well to assemblages found in the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm and the Salzgitter–Salder sections (Figs. 3 and 4).

Above, intervals yielding less diverse foraminiferal assemblages (Fig. 5) indicate a stressed bottom-water environment. Less diverse agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages from the upper Turonian to middle Coniacian from the Dover–Langdon Stairs mainly consist of tubular and other epifaunal or shallow infaunal taxa (Fig. 5), which indicate highly oligotrophic bottom-water conditions according to the TROX model (Fig. 9). Murray et al. (2011) relate the consistent appearance of tubular taxa to the existence of tranquil bottom-water currents.

The agglutinated foraminiferal barren intervals, which are above the Caburn Marl up to above the Lighthouse Down hardgrounds, above the Navigation hardgrounds, and at the East Cliff Flint (Fig. 5), indeed yield abundant calcareous benthic foraminifera (own observation), which suggest a loss of agglutinated foraminifera during taphonomic or diagenetic processes. Alve (1996) and Kuhnt et al. (2000) described depletion of agglutinated foraminiferal taxa from recently deposited sediments.

Figure 11Correlation of agglutinated foraminiferal acmes and relative abundances of deep infaunal foraminifera of the Salzgitter–Salder and Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm sections; foraminiferal acmes are indicated by grey bars. The Salzgitter–Salder log is redrawn after Niebuhr et al. (2007), and the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm log is redrawn after Appfel (1993); for log legend see Fig. 2.

6.4 Inter-regional implications

The gradual increase in relative abundances of deep infaunal foraminifera is clearly visible in both the Salzgitter–Salder and Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm sections (Fig. 11). It properly marks the transition from the Turonian nutrient crisis with widespread oligotrophic conditions throughout the European shelf sea towards more mesotrophic conditions in the Coniacian. A distinct maximum of relative abundances of deep infaunal foraminifera shortly below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary in both German sections coincides with higher nutrient availability in the upper water layers proposed by Jarvis et al. (2021). An agglutinated foraminiferal acme of Bulbobaculites problematicus related to this maximum can be correlated inter-regionally. Furthermore, acmes of Ammolagena contorta in the upper Turonian around the Micraster Marl and in the lower Coniacian occur contemporaneously in Salzgitter–Salder and Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm. These acmes probably reflect increased relative water depth with low sediment accumulation, favouring the bloom of attached agglutinated foraminifera (see the discussion in Sect. 6.1).

In this study, Turonian–Coniacian agglutinated foraminiferal assemblages from Salzgitter–Salder (GSSP) and other European sections from the temperate realm were studied to yield additional stratigraphic and paleoenvironmental information. To ensure the stratigraphical correlation, stable δ13Ccarb patterns of the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section from the Münsterland Cretaceous Basin were obtained and correlated with other published European reference sections. From three sections a total of 14 259 agglutinated foraminiferal specimens could be assigned to 87 different taxa. While residues from Dover (SE England) contain mainly low-diversity foraminiferal assemblages, those from Salzgitter–Salder and the Münsterland Cretaceous Basin are highly diverse with Fisher alpha indices up to 22.9. The most common taxa recorded in these deposits are Ammobaculites aff. agglutinans, Ammolagena contorta, Arenobulimina preslii, Ammosphaeroidina pseudopauciloculata, Bathysiphon sp., Bulbobaculites problematicus, Eggerellina brevis, Glomospira gordialis, and Psammosphaera irregularis. The occurrence of all morphogroups of agglutinated foraminifera and the calculated diversities imply normal marine settings and oligotrophic to mesotrophic bottom-water conditions for the German basins, as well as partly restricted environments for the Turonian–Coniacian at Dover. Nevertheless, a partial loss of agglutinated foraminifera in samples from Dover due to dissolution and/or diagenetic effects cannot be excluded, so all further interpretation remains doubtful.

However, agglutinated foraminiferal acmes can be used to correlate different sections and enable strong paleoenvironmental implications.

Three distinct acmes of Ammolagena contorta occur in the Turonian–Coniacian (perplexus to lower striatoconcentricus zones, lower scupini Zone, hannovrensis Zone). These acmes are like associated with a shift to more oligotrophic conditions which favoured the bloom of the attached taxon Ammolagena contorta.

An acme of Bulbobaculites problematicus is notable in the upper scupini Zone shortly below the Turonian–Coniacian boundary. This species is a deep infaunal taxa indicating enhanced nutrient availability in bottom waters for this interval.

Overall, agglutinated foraminiferal morphogroups display a gradual shift from oligotrophic conditions expressed through the Turonian nutrient crisis towards more mesotrophic conditions in the latest Turonian and Coniacian.

All recorded genera or species are named in the taxonomical reference list alphabetically sorted. First descriptions and the literature used for determination are mentioned in the synonymy lists of the taxa. Only commonly occurring and important species are described in detail. All mentioned references for the synonymy list are not included in the reference list.

Plate A1Middle Turonian to lower Coniacian agglutinated foraminifera from northern Europe; scale bars are 100 µm. (a) Bathysiphon sp., Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (b) Bathysiphon sp., Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (c) Psammosiphonella sp., Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (d) Psammosiphonella sp., Salzgitter–Salder, –50.00 m. (e) Nothia sp. (pyritised), Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 50.00 m. (f) Hippocrepina depressa, Salzgitter–Salder, 25.00 m. (g) Ammodiscus glabratus, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (h) Ammodiscus peruvianus, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (i) Ammodiscus peruvianus, Salzgitter–Salder, −70.00 m. (j) Ammodiscus tenuissimus, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (k) Ammolagena clavata, Salzgitter–Salder, −70.00 m. (l) Lituotuba lituoformis, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (m) Dolgenia pennyi, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (n) Ammodiscus cretaceus, Salzgitter–Salder, −70.00 m. (o) “Glomospira” irregularis, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (p) Caudammina ovula, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (q) Caudammina ovula, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (r) Saccammina grzybowskii, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (s) Glomospira charoides, Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 0.00 m. (t) Pseudonodosinella parvula, Salzgitter–Salder, −30.00 m. (u) Pseudonodosinella nodulosa, Salzgitter–Salder, −30.00 m. (v) Eobigenerina variabilis, Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm, 0.00 m. (w) Pavigenerina sp. 3, Salzgitter–Salder, −30.00 m. (x) Gerochammina stanislawi, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (y) Rectogerochammina aff. eugubina, Salzgitter–Salder, −50.00 m. (z) Spiroplectammina sp., Salzgitter–Salder, −10.00 m.

-

Agathamminoides serpens (Grzybowski, 1898)

-

pars 1898. Ammodiscus serpens Grzybowski: p. 285, pl. 10, fig. 31 (non figs. 32 and 33)

-

1993. Glomospira serpens (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Geroch, p. 256, pl. 6, figs. 2–5

-

2005. “Glomospira” serpens (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 189, pl. 27, figs. 1a–6b

-

2021. Agathamminoides serpens (Grzybowski); Kaminski et al., p. 347, pl. 2, fig. 11

Remarks. This species is typical for bathyal to abyssal settings (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Ammoanita sp.

Plate 1, fig. h

Occurrence. Rare in the Coniacian from Dover–Langdon Stairs.

-

Ammobaculites aff. agglutinans (d'Orbigny, 1846)

Plate 1, fig. e

-

1846. Spirolina agglutinans d'Orbigny: p. 137, pl. 7, figs. 10–12

-

1952. Ammobaculites agglutinans (d'Orbigny); Bartenstein, p. 318, pl. 1, fig. 1a–c; pl. 2, figs. 10–16

-

2005. Ammobaculites agglutinans (d'Orbigny); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 324, pl. 70, figs. 1–8

-

2021. Ammobaculites agglutinans (d'Orbigny); Besen et al., p. 413, fig. 7g

Description. Initial chambers arranged involute planispiral, last four chambers uniserial and more broad than high.

Remarks. This species is usually observed in deeper depositional settings (e.g. Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005) and is reported from Upper Cretaceous deposits from the Barents Sea (Campanian to Maastrichtian; Setoyama et al., 2011) and the Labrador margin (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005). Specimens from this study are generally less robust than Ammobaculites agglutinans (d'Orbigny, 1846). Besen et al. (2021) report this species from the Cenomanian to Turonian from the Lower Saxony Basin.

Occurrence. Common in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Ammodiscus cretaceus (Reuss, 1845)

Plate A1, fig. n

-

1845. Operculina cretacea Reuss: p. 35, pl. 13, figs. 64, 65

-

1934. Ammodiscus cretacea (Reuss); Cushman, p. 45

-

2005. Ammodiscus cretaceus (Reuss); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 145, pl. 14, figs. 1a–10

-

2021. Ammodiscus cretaceus (Reuss); Besen et al. 2021, p. 406, fig. 6l

Description. Test planispiral with 8 to 11 whorls, evolute with distinct sutures. The final whorls have increasing width and may have radial striations. Finely agglutinated and smooth finish.

Occurrence. Common to rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins, rare in Dover.

-

Ammodiscus glabratus Cushman and Jarvis, 1928

Plate A1, fig. g

-

1928. Ammodiscus glabratus Cushman and Jarvis: p. 87, pl. 12, fig. 6a, b

-

2005. Ammodiscus glabratus Cushman and Jarvis; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 148, pl. 15, figs. 1a–6

-

2011. Ammodiscus glabratus Cushman and Jarvis; Kaminski et al., p. 85, pl. 1, fig. 10

-

2021. Ammodiscus glabratus Cushman and Jarvis; Besen et al., p. 406, fig. 6m.

Description. Planispiral with about 10 whorls, involute, biconcave. Width slowly increases, while thickness increases rapidly in the last whorls.

Remarks. This species was previously reported to range from the Santonian to Eocene (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005; Kaminski et al., 2011). This study extends the range of A. glabratus, while Besen et al. (2021) already observed the species in the Cenomanian to Turonian from the Lower Saxony Basin. A. glabratus indicates bathyal settings (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Common to rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Ammodiscus peruvianus Berry, 1928

Plate A1, figs. h–i

-

1928. Ammodiscus peruvianus Berry: p. 392, fig. 27

-

2005. Ammodiscus peruvianus Berry; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 157, pl. 18, figs. 1a–6

-

2021. Ammodiscus peruvianus Berry; Besen et al., p. 406, fig. 6n

Remarks. A. peruvianus usually is reported from bathyal to abyssal deposits (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Ammodiscus tenuissimus Grzybowski, 1898

Plate A1, fig. j

-

1898. Ammodiscus tenuissimus Grzybowski: p. 282, pl. 10, fig. 35

-

2005. Ammodiscus tenuissimus Grzybowski; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 163, pl. 20, figs. 1a–7

-

2021. Ammodiscus tenuissimus Grzybowski; Besen et al., p. 406, fig. 6o

Remarks. A. tenuissimus is reported from middle bathyal to abyssal deposits (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Ammolagena clavata (Jones and Parker, 1860)

Plate A1, fig. k

-

1860. Trochammina irregularis (d'Orbigny) var. clavata Jones and Parker: not figured

-

1987. Ammolagena clavata (Jones and Parker); Loeblich and Tappan, p. 49, pl. 36, fig. 16

-

2005. Ammolagena clavata (Jones and Parker); Kaminski and Gradstein, pp. 165–168, pl. 21, fig. 21

-

2021. Ammolagena clavata (Jones and Parker); Besen et al., p. 404, fig. 6g–h

Remarks. Ammolagena clavata occurs predominantly in bathyal settings (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005). However, Besen et al. (2021) reported it from middle shelf deposits from the Cenomanian in the Lower Saxony Basin with assumed water depth not deeper than 50 m (Wilmsen, 2003).

Occurrence. Rare to very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Ammolagena contorta Waters, 1927

Plate 1, fig. d

-

1927. Ammolagena contorta Waters: p. 132, pl. 22, fig. 4

-

2017. Ammolagena contorta Waters; Setoyama et al., p. 211, pl. 1, fig. 2.

-

2021. Ammolagena contorta Waters; Besen et al., p. 404, fig. 6i

Description. Attached test with an oval and elongated proloculus which is only barely wider than the following slender tubular second chamber; often contorted appearance of the tubular part with an aperture at the open end of the tube, very finely agglutinated. General morphology of the tubular section is due to the incrusted medium.

Remarks. Setoyama et al. (2017) report A. contorta from bathyal settings from the Labrador margin, the Vøring Basin offshore of Norway, and the Barents Sea. Differs from A. clavata in its more slender proloculus, which is barely wider than the following tubular chamber.

Occurrence. Abundant in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Ammosphaeroidina pseudopauciloculata (Mjatliuk, 1966)

Plate 1, fig. h

-

1966. Cystamminella pseudopauciloculata Mjatliuk, p. 264, pl. 1, figs 5–8; pl. 2, fig. 6; pl. 3, fig. 3.

-

1988. Ammosphaeroidina pseudopauciloculata (Mjatliuk); Kaminski et al., p. 193, pl. 8, figs 3a–5.

-

2005. Ammosphaeroidina pseudopauciloculata (Mjatliuk); Kaminski and Gradstein, pp. 376–381, pl. 87a, b, figs. 1–5, 1–10

Remarks. The range of A. pseudopauciloculata was described by Kaminski and Gradstein (2005) as Campanian to Eocene. Findings of A. pseudopauciloculata in this study resemble the oldest observation of this species and extend the range of the taxon to the upper Turonian.

Occurrence. Abundant in the upper Turonian of the Bielefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section; otherwise very rare.

-

Arenobulimina barnardi Frieg and Price, 1982.

-

1982. Arenobulimina (Pasternakia) barnardi Frieg and Price: p. 58, pl. 2.2, fig. f

-

1989. Arenobulimina (Pasternakia) barnardi (Frieg and Price); Frieg and Kemper, p. 90, pl. 2, figs. 1–5

Occurrence. Rare to very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Arenobulimina bochumensis Frieg, 1980

-

1980. Arenobulimina (Pasternakia) bochumensis Frieg: p. 235, pl. 2, figs. 1–3

-

1980. A. (Arenobulimina) macfadyeni elongata Barnard and Banner, p. 403, pl. 2, fig. 7, pl. 6, figs. 2–4

-

1989. A. (Pasternakia) bochumensis Frieg; Frieg et al., p. 90, pl. 3, figs. 1–29

-

2021. Arenobulimina bochumensis Frieg; Besen et al., p. 422, fig. 8k

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Arenobulimina preslii (Reuss, 1845)

-

1845. Bulimina preslii Reuss: p. 38, pl. 13, fig. 72

-

1972. Arenobulimina preslii (Reuss); Voloshina, p. 59, pl. 1, figs. 2–3

-

2021. Arenobulimina preslii (Reuss); Besen et al., p. 422, fig. 8l

Occurrence. Rare to very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian.

-

Arenobulimina truncata (Reuss, 1844)

-

1844. Bulimina truncata Reuss: p. 215, pl. 8, fig. 73

-

1937. Arenobulimina truncata (Reuss); Cushman, p. 40, pl. 4, figs. 15, 16

-

2021. Arenobulimina truncata (Reuss); Besen et al., p. 422, fig. 8m

Occurrence. Common to rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins, rare in the Dover–Langdon Stairs section.

-

Arenobulimina sp. indet.

Remarks. Non-determinable specimens from the genus Arenobulimina.

-

Ataxophragmium depressum (Perner, 1892)

-

1892. Bulimina depressum Perner: p. 55, pl. 3, fig. 3

-

1972. Ataxophragmium depressum (Perner); Voloshina, p. 104, pl. 11, fig. 6

-

2021. Ataxophragmium depressum (Perner); Besen et al., p. 423, fig. 8n–o

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Ataxophragmium variabile (d'Orbigny, 1840)

-

1840. Bulimina variabile d'Orbigny: p. 40, pl. 4, figs. 9–11

-

1980. Ataxophragmium variabile (d'Orbigny); Gawor-Biedowa, p. 21, pl. 2, figs. 16, 17

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Ataxophragmium sp. indet

Remarks. Specimens not further determined belonging to the genus Ataxophragmium.

-

Bathysiphon sp.

Plates 1, fig. a; A1, figs. a–b

Description. Test tubular unbranched, finely agglutinated, always fragmented.

Remarks. All counts were divided by the factor of 5 to reduce the effect of multiple fragmentation of single specimens of this genus on statistical analysis.

Occurrence. Abundant to common.

-

Bicazammina sp.

Remarks. Specimens of this species are often poorly preserved. Most of the specimens likely belong to Bicazammina lagenaria as this species was already observed in Turonian deposits from the Lower Saxony Basin (Besen et al., 2021).

Occurrence. Very rare in Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Bulbobaculites problematicus (Neagu, 1962)

Plate 1, figs. f, g

-

1962. Ammobaculites agglutinans problematicus Neagu: p. 61, pl. 2, figs. 22–24

-

1970. Ammobaculites problematicus (Neagu); Neagu, p. 39, pl. 6, figs. 1–5

-

1990. Haplophragmium problematicum (Neagu); Kuhnt, p. 312, pl. 4, figs. 3–9

-

1990. Bulbobaculites problematicus (Neagu); Kuhnt and Kaminski, p. 465, text fig. 5, 5A

-

2013. Bulbobaculites problematicus (Neagu); Holbourn et al., p. 86–87, figs. 1–2.

-

2021. Bulbobaculites problematicus (Neagu); Besen et al., p. 413, fig. 7i

Description. Initial chambers are small, streptospiral coiled, followed by a uniserial rectilinear part of variable length usually consisting of three to four chambers. The chambers are subcylindrical and inflated with distinct depressed sutures; walls are non-alveolar and finely to coarsely agglutinated. The last chamber possesses a rounded terminal aperture which usually has a smooth collar.

Remarks. Kuhnt (1990) described a tendency towards a reduced and more rectilinear uniserial part of B. problematicus in the Turonian and Coniacian, which can also be observed for specimens from the German basins (see also Besen et al., 2021). Nevertheless, specimens with a longer uniserial which can be less rectilinear also occur in our samples. Overall, specimens found in the German basins resemble those from the Polish Carpathians described by Huss (1966).

Occurrence. Abundant to common in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Caudammina ovula (Grzybowski, 1896)

Plate A1, figs. p–q

-

1896. Reophax ovulum Grzybowski: p. 276, pl. 8, figs. 19–21

-

1988. Hormosina ovulum ovulum (Grzybowski); Kaminski et al., p. 186, pl. 2, fig. 10

-

2005. Caudammina ovula (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 233, pl. 41, figs. 1a–8

-

2021. Caudammina ovula (Grzybowski); Besen et al., p. 405, fig. 6j

Remarks. C. ovula commonly occurs in bathyal to abyssal settings (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Common to rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Caudammina sp.

Remarks. Broken specimens which probably refer to C. ovula.

Occurrence. Rare.

-

Clavulinoides sp.

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Dolgenia pennyi (Cushman and Jarvis, 1928)

Plate A1, fig. m

-

1928. Ammodiscus pennyi Cushman and Jarvis: p. 87, pl. 12, figs. 4, 5

-

2005. Ammodiscus pennyi Cushman and Jarvis; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 155, pl. 17, figs. 1–6

-

2011. Dolgenia pennyi Cushman and Jarvis; Setoyama et al., p. 271, pl. 3, fig. 12a–b

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Dorothia conula (Reuss, 1845)

-

1845. Textularia conulus Reuss: pp. 38, 39, pl. 8, fig. 59a–b, pl. 13, fig. 75a–b

-

1937. Dorothia conula (Reuss); Cushman, pp. 76, 77, pl. 8, figs. 11–14

-

2022. Dorothia conula (Reuss); Besen et al., p. 175, text-fig. 5K

Occurrence. Very rare in the Coniacian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Eggerellina brevis (d'Orbignyi, 1840)

-

1840. Bulimina brevis d'Orbigny: p. 41, pl. 4, figs. 13, 14

-

1972. Eggerellina brevis (d'Orbigny); Voloshina, p. 92, pl. 9, figs. 2, 3; pl. 21, fig. 2

-

2000. Eggerellina brevis (d'Orbigny); Frenzel, p. 34, pl. 7, fig. 1, text-fig. 13

-

2021. Eggerellina brevis (d'Orbigny); Besen et al., p. 419, fig. 8d–e

Occurrence. Common to very rare.

-

Eggerellina mariae Ten Dam, 1950

-

1950. Eggerellina mariae Ten Dam: p. 15, pl. 1, fig. 17a–e

-

1975. Eggerellina mariae Ten Dam; Magniez-Jannin, p. 94, pl. 6, figs. 12–21

-

2000. Eggerellina mariae Ten Dam; Szarek et al., p. 451, pl. 4, figs. 10–15

-

2021. Eggerellina mariae Ten Dam; Besen et al., p. 420, fig. 8f

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Eobigenerina kuhnti Cetean et al., 2011b

-

2011b. Eobigenerina kuhnti Cetean et al.: p. 22, pl. 1, figs. 13–16

-

2021. Eobigenerina kuhnti Cetean et al.; Besen et al., p. 416, fig. 7n

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Eobigenerina variabilis (Vašíček, 1947)

Plate A1, fig. v

-

1947. Bigenerina variabilis Vašíček: p. 246, pl. 1, figs. 10–12

-

1970. Pseudobolivina variabilis (Vašíček); Neagu, p. 41, pl. 5, figs. 13–16

-

2011b. Eobigenerina variabilis (Vašíček); Cetean et al., pp. 6, 7, pl. 1, figs. 1–12

-

2021. Eobigenerina variabilis (Vašíček); Besen et al. p. 417, fig. 7o

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Falsogaudryinella sp.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Coniacian from the Dover–Langdon Stairs section.

-

Gaudryinella irregularis Tappan, 1943.

-

1943. Gaudryinella irregularis Tappan: p. 493, pl. 78, figs. 22–24

-

1990. Gaudryinella irregularis Tappan; Weidich, p. 104, pl. 9, figs. 10–11; pl. 35, fig. 7

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Gerochammina aff. lenis (Grzybowski, 1896).

-

1896. Spiroplectina lenis Grzybowski: p. 288, pl. 9, figs. 24, 25

-

1990. Gerochammina lenis (Grzybowski); Neagu, p. 260, pl. 2, figs. 22–32, p. 254, pl. 4, figs. 28–31

Remarks. The taxon Gerochammina lenis has its reported FO in the Campanian (Neagu, 1990). The specimens from the Coniacian from Germany resemble G. lenis in their well-developed early trochospiral stage and a following biserial part that is less filiform than observed in G. stanislawi. Due to the extended stratigraphical gap our specimens are assigned affinity to G. lenis.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Coniacian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Gerochammina stanislawi Neagu, 1990

Plate A1, fig. x

-

1990. Gerochammina stanislawi Neagu: p. 253, pl. 1, figs. 1–26

-

2021. Besen et al., p. 417, fig. 7q

Occurrence. Common to very rare.

-

Glomospira charoides (Jones and Parker, 1860)

Plate A1, fig. s

-

1860. Trochammina squamata var. charoides Jones and Parker: p. 304

-

1990. Glomospira charoides (Jones and Parker); Berggren and Kaminski, p. 60, pl. 1, fig. 2

-

2001. Repmanina charoides (Jones and Parker); Alegret and Thomas, p. 300, pl. 10, fig. 11

-

2011. Repmanina charoides (Jones and Parker); Kaminski et al., p. 86, pl. 1, figs. 17a–b

-

2021. Repmanina charoides (Jones and Parker); Besen et al., p. 408, fig. 6r

-

2021. Glomospira charoides (Jones and Parker); Wolfgring et al., p. 5, fig. 4.6

Occurrence. Common to very rare.

-

Glomospira sp. 1

-

2021. Besen et al., p. 407, fig. 6p

Remarks. This species resembles G. diffundens in its initial glomospirally coiling, two irregular planispiral whorls, and a fine agglutinated test. However, Glomospira sp. 1 is usually smaller than G. diffundens and appears much earlier in the Cenomanian (Besen et al., 2021) than G. diffundens with its FO in the late Campanian.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Glomospira gordialis (Jones and Parker, 1860)

Plate 1, fig. i

-

1860. Trochammina squamata (Jones and Parker) var. gordialis Jones and Parker: pp. 292–307 (no type figure given)

-

1990. Glomospira gordialis (Jones and Parker); Berggren and Kaminski, p. 73, pl. 1, fig. 1

-

2005. Glomospira gordialis (Jones and Parker); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 181, pl. 25, figs. 1–8.

-

2021. Glomospira gordialis (Jones and Parker); Besen et al., p. 407, fig. 6q

Remarks. Bathymetrical preferences of G. gordialis are described as bathyal to abyssal (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Common to rare.

-

“Glomospira” irregularis (Grzybowski, 1898)

Plate A1, fig. o

-

1898. Ammodiscus irregularis Grzybowski: p. 285, pl. 11, figs. 2, 3

-

1984. Glomospira? irregularis (Grzybowski); Hemleben and Troester, p. 519, pl. 1, fig. 22

-

1993. Glomospira irregularis (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Geroch, p. 256, pl. 6, figs. 6–8b

-

2005. “Glomospira” irregularis (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 185, pl. 26, figs. 1a–7

Remarks. “Glomospira” irregularis usually occurs in bathyal to abyssal settings (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Rare.

-

Hagenowella elevata (d'Orbignyi, 1840)

-

1840. Globigerina elevata d'Orbigny: p. 34, pl. 3, figs. 15, 16

-

1982. Hagenowella elevata (d'Orbigny); Frieg and Price, p. 55, pl. 2.1, fig. 1; pl. 2.2, figs. a–b

-

2021. Hagenowella elevata (d'Orbigny); Besen et al., p. 423, fig. 8p

Occurrence. Common in the upper Turonian from the Dover–Langdon Stairs section; otherwise rare to very rare.

-

Hagenowella obesa (Reuss, 1851)

-

1851. Bulimina obesa Reuss: p. 40, pl. 4, fig. 12; pl. 5, fig. 1

-

1982. Hagenowella obesa (Reuss); Frieg and Price, p. 56, pl. 2.2, figs. c–d; pl. 2.3, fig. i

-

2000. Hagenowella obesa (Reuss); Frenzel, p. 45, pl 6, figs. 10–12, text-fig. 17

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Haplophragmoides aff. bubiki Setoyama et al., 2011

-

2011. Haplophragmoides bubiki, Setoyama et al.: p. 273, pl. 6, figs. 12a–b, pl. 7, figs. 9a–c, 10a–c

Remarks. The specimens from this study resemble H. bubiki but are of much older age.

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Haplophragmoides bulloides (Beissel, 1891)

-

1891. aff. Haplophragmium bulloides Beissel: p. 17, pl. 2, figs. 1–3, pl. 4, figs. 24–30

-

1966. Haplophragmoides bulloides (Beissel); Huss, p. 23, pl. 3, figs. 17–24

Occurrence. Rare to very rare from the Bieldefeld–Ostwestfalendamm section.

-

Haplophragmoides eggeri Cushman, 1926

-

1926. Haplophragmoides eggeri Cushman: p. 583, pl. 15, fig. 1a, b

-

2005. Haplophragmoides eggeri Cushman; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 342, pl. 75, figs. 1–6

Occurrence. Very rare from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Haplophragmoides aff. stomatus (Grzybowski, 1898)

-

1898. Trochammina stomata Grzybowski: p. 290, pl. 11, figs. 26, 27

-

1993. Haplophragmoides stomatus Grzybowski; Kaminski and Geroch, p. 311, pl. 11, figs. 1a–2b

-

2005. Haplophragmoides stomatus Grzybowski; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 357, pl. 80, figs. 1a–6b

Remarks. Specimens of H. aff. stomatus resemble H. eggeri despite a smoother appearance. H. stomatus (Grzybowski, 1898) is of much younger age (e.g. Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005) than specimens from this study.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Haplophragmoides suborbicularis (Grzybowski, 1896)

-

1896. Cyclammina suborbicularis Grzybowski: p. 63, pl. 9, figs. 5–6

-

1988. Haplophragmoides suborbicularis (Grzybowski); Kaminski et al., p. 189, pl. 5, figs. 12–13

-

2005. Haplophragmoides suborbicularis (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Gradstein, pp. 358–360, pl. 81, figs. 1–4

-

2021. Haplophragmoides suborbicularis (Grzybowski); Besen et al., p. 412, fig. 6e

Remarks. This species was previously reported from bathyal settings (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Haplophragmoides walteri (Grzybowski, 1898)

-

Trochammina walteri Grzybowski: 1898, p. 290, pl. 11, fig. 31

-

1993. Haplophragmoides walteri Grzybowski; Kaminski and Geroch, p. 263, pl. 10, figs. 3a–7c, p. 309, pl. 10, figs. 3a–c

-

2005. Haplophragmoides walteri Grzybowski; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 365, pl. 83, figs. 1–6

-

2021. Haplophragmoides walteri Grzybowski; Besen et al., p. 412, fig. 7f

Occurrence. Very rare in the German basins.

-

Haplophragmoides sp. indet.

Remarks. Non-determinable specimens from the genus Haplophragmoides.

-

Hemisphaerammina batalleri Loeblich and Tappan, 1957

-

1957. Hemisphaerammina batalleri: Loeblich and Tappan, p. 224, pl. 72, fig. 3

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Hemisphaerammina glandiformis Hercogová and Kriz, 1983

-

1983. Hemisphaerammina glandiformis Hercogová and Kriz: p. 210, pl. 5, fig. 5a, b.

Occurrence. Rare to very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Heterostomella carinata (Franke, 1914)

Plate 1, fig. o

-

1914. Gaudryina carinata Franke: p. 431, pl. 27, figs. 4–6

-

1992. Heterostomella carinata (Franke); Gawor-Biedowa, pp. 35–37, pl. 3, figs. 3

-

2022. Gaudryina carinata Franke; Besen et al., p. 175, text-fig. 5L

Remarks. Heterostomella carinata occurs first in the lower Coniacian in the Lower Saxony and Münsterland basins; it is reported for the upper Turonian in the Saxony Cretaceous Basin (Besen et al., 2022a).

Occurrence. Common to rare in the lower Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Hippocrepina depressa Vašíček, 1947

Plate A1, fig. f

-

1947. Hippocrepina depressa Vašíček: p. 243, pl. 1, fig. 1a, b

-

1995. Hippocrepina depressa Vašíček; Bubík, p 82, pl. 8, fig. 13

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Hormosinella fusiformis Kaminski et al., 2011

-

2011. Hormosinella fusiformis Kaminski et al.: p. 87, pl. 2, figs. 6–12

Remarks. This species was previously reported from the Santonian to Maastrichtian and recently from the Cenomanian from the Lower Saxony Basin (Besen et al., 2021).

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Hormosinelloides guttifer (Brady, 1884)

-

1884. Reophax guttifera Brady: p. 278

-

2011. Hormosinelloides guttifer (Brady); Kaminski, p. 87, pl. 2, fig. 13

Remarks. Hormosinelloides guttifer is reported from upper bathyal to abyssal environments (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Hyperammina elongata Brady, 1884

-

1884. Hyperammina elongata Brady: p. 257, pl. 23, figs. 4, 7–10

-

1995. Hyperammina elongata Brady; Bubík, p. 83, pl. 8, fig. 13

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Kechenotiske sp. indet

Remarks. Specimens not further determined belonging to the genus Kechenotiske. They differ from Tipeammina in their much finer agglutinated test and smooth finish.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Lagenammina difflugiformis (Brady, 1879)

-

1879. Reophax difflugiformis Brady: p. 51, pl. 4, fig. 3

-

1990. Lagenammina difflugiformis (Brady); Charnock and Jones, p. 146, pl. 1, fig. 2, pl. 13, fig. 2

-

2022. Lagenammina difflugiformis (Brady); Besen et al., p. 177, text-fig. 5c

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Lituotuba lituiformis (Brady, 1879)

Plate A1, fig. l

-

1879. Trochammina lituiformis Brady: p. 59, pl. 5, fig. 16

-

1990. Lituotuba lituiformis (Brady); Kuhnt, p. 318, pl. 1, figs. 17, 18

-

2005. Lituotuba lituiformis (Brady); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 287, pl. 38, figs. 1–8

-

2011. Lituotuba lituiformis (Brady); Kaminski et al., p. 88, pl. 3, fig. 12

-

2021. Lituotuba lituiformis (Brady); Besen et al., p. 408, fig. 6s

Remarks. This species is reported from bathyal to abyssal settings (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Rare to very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Marssonella trochus (d'Orbigny, 1840)

-

1840. Textularia trochus d'Orbigny: 1840

-

1953. Marssonella trochus (d'Orbigny); Barnard and Banner, p. 204, text-figs. 5o–s

-

2000. Marssonella trochus (d'Orbigny); Frenzel, pp. 52–53, pl. 5, fig. 7

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Nothia sp. indet.

Plate A1, fig. e

Remarks. Large fragments belonging to this genus are usually flattened and pyritised. All counts were divided by the factor of 5 representing the minimum fragmentation factor.

Occurrence. Very rare.

-

Parvigenerina sp. 3 (Kuhnt, 1990)

Plate A1, fig. w

-

1990. Pseudobolivina sp. 3 Kuhnt: p. 324, pl. 6, fig. 5.

-

2011. Parvigenerina sp. 3 (Kuhnt); Kaminski et al., p. 93, pl. 5, figs. 13–14.

-

2021. Parvigenerina sp. 3 (Kuhnt); Besen et al., p. 416, fig. 7m

Remarks. This species possesses a biserial part which is characterised by a change of growth direction of about 90∘. Parvigenerina sp. 3 was previously reported from the Santonian and Campanian (Kuhnt, 1990). The findings of this study extend the range into the Turonian.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Placentammina placenta (Grzybowski, 1898)

-

1898. Reophax placenta Grzybowski: p. 276, pl. 10, figs. 9, 10

-

1993. Saccammina placenta (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Geroch, p. 249, pl. 2, figs. 5–7

-

2005. Placentammina placenta (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 136, pl. 11, figs. 1–6

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Placopsilina sp. indet

Remarks. One broken specimen from the Turonian from the Dover–Langdon Stairs section. Not further determined.

-

Praecystammina sp.

Remarks. One specimen recorded in the upper Turonian from the Salzgitter–Salder section resembles P. globigerinaeformis Krasheninnikov, 1973, following the definition from Moullade et al. (1988).

-

Psammosiphonella spp.

Plates 1, fig. b; A1, fig. c–d

Description. Tubular fragments, test cylindrical, coarsely to finely agglutinated. More coarsely agglutinated than Bathysiphon. All counts were divided by the factor of 5 to reduce the effect of multiple fragmentation of single specimens of this genus on statistical analysis.

Occurrence. Common to rare.

-

Psammosphaera fusca Schultze, 1875

-

1875. Psammosphaera fusca Schultze: p. 113, pl. 2, fig. 8a–f

-

2005. Psammosphaera fusca Schultze; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 125, pl. 8, figs. 1–9

-

2021. Psammosphaera fusca Schultze; Besen et al., p. 402, fig. 6b

-

2022. Psammosphaera fusca Schultze; Besen et al., pp. 177–178, text-fig. 5A

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Psammosphaera irregularis (Grzybowski, 1896)

Plate 1, fig. c

-

1896. Keramosphaera irregularis Grzybowski: p. 273, pl. 8, figs. 12, 13

-

2005. Psammosphaera irregularis (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 131, pl. 9, figs. 1–9

-

2022. Psammosphaera irregularis (Grzybowski); Besen et al., p. 178, text-fig. 5B

Remarks. P. irregularis is reported from bathyal settings (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005).

Occurrence. Abundant to rare.

-

Pseudonodosinella nodulosa (Brady, 1879)

Plate A1, fig. u

-

1879. Reophax nodulosa Brady: p. 52, pl. 4, figs. 7–8

-

2005. Pseudonodosinella nodulosa (Brady); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 259, pl. 49, figs. 1–9

-

2017. Pseudonodosinella nodulosa (Brady); Setoyama, p. 193, pl. 1, fig. 21

-

2021. Pseudonodosinella nodulosa (Brady); Besen et al., p. 410, fig. 7b

Remarks. This species is reported to occur in bathyal to upper abyssal conditions (Kaminski and Gradstein, 2005). The first report occurrence of this species is late Senonian. Besen et al. (2021) documented P. nodulosa in the Cenomanian.

Occurrence. Common to rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Pseudonodosinella parvula (Huss, 1966)

Plate A1, fig. t

-

1966. Reophax parvulus Huss: p. 21, pl. 1, figs. 26–30

-

1995. Pseudonodosinella parvula (Huss); Geroch and Kaminski, p. 118, pl. 2, figs. 1–19

-

2011. Pseudonodosinella parvula (Huss); Kaminski et al., p. 88, pl. 3, fig. 11

-

2017. Pseudonodosinella parvula (Huss); Setoyama et al., p. 193, pl. 1, fig. 22

-

2021. Pseudonodosinella parvula (Huss); Besen et al., p. 410, fig. 7c

Occurrence. Common to rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Pseudotextulariella cretosa (Cushman, 1932)

-

1932. Textulariella cretosa Cushman: p. 97, pl. 11, figs. 17–19

-

1953. Pseudotextulariella cretosa (Cushman); Barnard and Banner, p. 198, text-fig. 6 B–I

-

1980. Pseudotextulariella cretosa (Cushman); Frieg, p. 238, pl. 2, fig. 12, 13

-

2021. Pseudotextulariella cretosa (Cushman); Besen et al., p. 424, fig. 8s

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Rectogerochammina aff. eugubina Kaminski et al., 2010

Plate A1, fig. y

-

2010. Rectogerochammina eugubina Kaminski et al.: p. 122, text-figs. 1–2

-

2011. Rectogerochammina eugubina Kaminski et al.; Kaminski et al., p. 94, pl. 5, figs. 17a–b

-

2021. Rectogerochammina eugubina Kaminski et al.; Besen et al., p. 417, fig. 7p

Remarks. Rectogerochammina aff. eugubina resembles R. eugubina in its high trochospiral coiling followed by a biserial part of about four chambers and differs from it in having a lax-uniserial terminal part out of four chambers, not a rectilinear uniserial part. Besen et al. (2021) described specimens from the Cenomanian and Turonian from the Lower Saxony Basin. These specimens also possess a terminal lax-uniserial part and can likely be assigned to R. aff. eugubina. Aside from that, R. eugubina was documented as not being older than Campanian age.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Recurvoides spp.

Remarks. All specimens belonging to the genus Recurvoides.

-

Reophax globosus Sliter, 1968

-

1968. Reophax globosus Sliter: p. 43, pl. 1, fig. 12

-

2005. Reophax globosus Sliter; Kaminski and Gradstein, pp. 269–271, pl. 52, figs. 1–6

-

2022. Reophax globosus Sliter: Besen et al., p. 178, text-fig. 5F

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Reophax scorpiurus de Montfort, 1808

-

1808. Reophax scorpiurus de Montfort: p. 331

-

1971. Reophax scorpiurus de Montfort; Fuchs, p. 9, pl. 1, fig. 3

Occurrence. Very rare in the Coniacian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Reophax subfusiformis Earland, 1933 emend. Höglund, 1947

-

1933. Reophax subfusiformis Earland: p. 74, pl. 2, figs. 16–19

-

2005. Reophax subfusiformis (Earland); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 275, pl. 54, figs. 1–8

-

2021. Reophax subfusiformis (Earland); Besen et al., pp. 409–410, fig. 6a

-

2022. Reophax subfusiformis (Earland); Besen et al., p. 178, text-fig. 5G

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Reophax sp. indet

Remarks. Undeterminable specimens from the genus Reophax.

-

Rhabdammina sp.

Remarks. Tubular branched form. All counts were divided by the factor of 5 to reduce the effect of multiple fragmentation of single specimens of this genus on statistical analysis.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Rzehakina minima Cushman and Renz, 1946

-

1946. Rzehakina epigona (Rzehak) var. minima Cushman and Renz: p. 24, pl. 3, fig. 5

-

2005. Rzehakina minima Cushman and Renz; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 215, pl. 35, figs. 1a–10

-

2011. Rzehakina minima Cushman and Renz; Kaminski et al., p. 86, pl. 1, fig. 19

-

2021. Rzehakina minima Cushman and Renz; Besen et al., p. 409, fig. 6t

Remarks. Kaminski and Gradstein (2005) described this species as related to bathyal to abyssal settings.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Saccammina grzybowskii (Schubert, 1902)

Plate A1, fig. r

-

1902. Reophax grzybowskii Schubert: p. 20, pl. 1, fig. 13a–b

-

1993. Saccammina grzybowskii (Schubert); Kaminski and Geroch, p. 248, pl. 2, figs. 1a–4b

-

2005. Saccammina grzybowskii (Schubert); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 132, pl. 10, figs. 1–9

-

2021. Saccammina grzybowskii (Schubert); Besen et al., pp. 401–402, fig. 6a

-

2022. Saccammina grzybowskii (Schubert); Besen et al., p. 179, text-fig. 5D

Occurrence. Common to very rare.

-

Saccammina sphaerica Brady, 1871

-

1871. Saccammina sphaerica Brady, p. 183.

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Spiroplectammina navarroana Cushman, 1932

Plate 1, figs. j–l

-

1932. Spiroplectammina navarroana Cushman: p. 96, pl. 11, fig. 14

-

1989. Spiroplectammina navarroana Cushman; Gradstein and Kaminski, p. 83, pl. 9, figs. 1a–12

-

2005. Spiroplectammina navarroana Cushman; Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 426, pl. 103, figs. 1a–12

-

2017. Spiroplectammina navarroana Cushman; Setoyama et al., p. 196, pl. 2, fig. 12.

-

2021. Spiroplectammina navarroana Cushman; Besen et al., p. 415, fig. 7j

Remarks. Kaminski and Gradstein (2005) describe this species as preferring bathyal to abyssal conditions.

Occurrence. Common in the middle Turonian and basal upper Turonian from the Salzgitter–Salder section; otherwise rare to very rare.

-

Spiroplectammina sp.

Plate A1, fig. z

Remarks. Fragmented specimens from the genus Spiroplectammina. They possibly belong to Spiroplectammina praelonga (Reuss, 1845), which was also found in the Turonian to Coniacian from the Saxony Cretaceous Basin (see Besen et al., 2022a).

Occurrence. Very rare in the Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Subbdelloidina haeusleri Frentzen, 1944

-

1944. Subbdelloidina haeusleri Frentzen: p. 332, pl. 18, figs. 12–22

-

1987. Subbdelloidina haeusleri Frentzen; Leary, p. 54, pl. 1, fig. 13

Occurrence. Rare to very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Subreophax scalaris (Grzybowski, 1896)

-

1896. Reophax guttifera (Brady) var. scalaria Grzybowski: p. 277, pl. 8, figs. 26a–b

-

1988. Subreophax scalaris (Grzybowski); Kaminski et al., p. 187, pl. 2, figs. 16–17

-

2005. Subreophax scalaris (Grzybowski); Kaminski and Gradstein, p. 278, pl. 55, figs 1–7

-

2011. Subreophax scalaris (Grzybowski); Kaminski et al., p. 87, pl. 3, fig. 7

-

2021. Subreophax scalaris (Grzybowski); Besen et al., p. 405, fig. 6k

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian from the Salzgitter–Salder section.

-

Tipeammina elliptica (Deecke, 1884)

-

1884. Rhabdammina elliptica Deecke: p. 23, pl. 1, fig. 1a, b

-

2004. Tipeammina elliptica (Deecke); Neagu, pl. 1, figs. 10–12, fig. 2

-

2021. Tipeammina elliptica (Deecke); Besen et al., p. 402, fig. 6c

-

2022. Tipeammina elliptica (Deecke); Besen et al., p. 179, text-fig. 5E

Occurrence. Very rare in the Turonian to Coniacian from the German basins.

-

Tipeammina sp. 1

-

2021. Tipeammina sp. 1, Besen et al., p. 403, fig. 6d–e

Remarks. Differs from T. elliptica in its much faster growth in diameter.

Occurrence. Rare to very rare.

-

Tolypammina sp. indet.

Remarks. Fragments from specimens from the genus Tolypammina.

-

Tritaxia tricarinata (Reuss, 1845)

-