the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Tropical ecosystem shifts at the Eocene–Oligocene transition in the southwestern Caribbean region

Raúl Trejos-Tamayo

Darwin Garzón

Diana Ochoa

Angelo Plata-Torres

Fabrizio Frontalini

Felipe Vallejo-Hincapié

Fátima Abrantes

Vitor Magalhães

Viviana Arias-Villegas

Carlos Jaramillo

Jaime Escobar

Jason H. Curtis

José-Abel Flores

Constanza Osorio-Tabares

Mónica Duque-Castaño

Erika Bedoya

Andrés Pardo-Trujillo

The Eocene–Oligocene transition (EOT; ∼ 34 Ma) marks a pivotal climatic shift from a warm, ice-free world to a cooler, glaciated climate driven by a significant decline in atmospheric pCO2 levels. This global cooling event, characterized by the first major Antarctic glaciation and a ∼ 50 m sea-level fall, triggered selective extinctions in marine ecosystems and restructured sedimentary processes, making it one of the most significant climatic events of the Cenozoic. While the global impacts of the EOT are well documented, its effects on the marine environment of NW South America remain poorly understood. This region's unique position as a connection between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans before the closure of the Central American Seaway provides a valuable window into tropical ecosystem responses during this period. This study integrates micropaleontological and geochemical data from the ANH-SJ-1 drill core in the Colombian Caribbean to evaluate the impacts of global climatic shifts on tropical marine ecosystems. Palynological indicators, including the terrestrialmarine () index, along with XRF-derived elemental ratios (, , , and ), reflect enhanced continental input during the EOT. These patterns suggest intensified erosion and detrital transport to bathyal depths, likely driven by rapid sea-level fall and hypopycnal flows. Calcareous nannofossil trophic indices reveal elevated surface productivity, likely fueled by increased continental nutrient influx, supported by higher ratios that indicate enhanced organic matter export to the seafloor. The resulting oxygen depletion favored infaunal over epifaunal benthic foraminifera, marking a shift in community structure. Improved carbonate preservation across the transition, evidenced by a shift from agglutinated to calcareous benthic foraminifera and higher ratios, reflects a deepening of the carbonate compensation depth (CCD), likely due to enhanced alkalinity from continental weathering. A positive δ13Corg excursion (∼ 0.84 ‰) aligns with global records and supports contributions from organic carbon oxidation, volcanic inputs, and weathering. Although limited by the number of available samples and low fossil abundances in some intervals, our multiproxy approach enables a coherent reconstruction of environmental dynamics. The ANH-SJ-1 record highlights the sensitivity of tropical systems to global climatic shifts and reinforces the importance of tropical data for understanding Cenozoic climate evolution and anticipating future ecosystem responses.

- Article

(5950 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(3254 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The late Eocene–early Oligocene interval marks a pivotal epoch in the Cenozoic climatic history, during which the planet transitioned from a warm, largely ice-free state (warmhouse world) to a cooler, glaciated climate (icehouse world) (Zachos et al., 2001; Coxall and Pearson, 2007; Speijer et al., 2020; Westerhold et al., 2020; Hutchinson et al., 2021). This shift, known as the Eocene–Oligocene transition (EOT; ∼ 34 Ma and lasting ∼ 790 kyr), was driven by a pronounced decrease in atmospheric pCO2 levels (DeConto and Pollard, 2003; Pearson et al., 2009), triggering global cooling (Liu et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2023a), the expansion of Antarctic ice sheets (Zachos et al., 1992; Galeotti et al., 2016), and a sea-level drop of about 50–60 m (Miller et al., 2008, 2009, 2020). These changes caused widespread marine regressions, triggered the development of strong meridional thermal gradients that influenced precipitation, increased the flux of terrestrial organic matter to the oceans, and reshaped marine ecosystems (Merico et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2008; Pearson et al., 2009; Hutchinson et al., 2021; De Lira Mota et al., 2023).

Regression-driven weathering of exposed carbonate platforms released dissolved inorganic carbon, increased ocean alkalinity, and deepened the carbonate compensation depth (CCD) (Rea and Lyle, 2005; Merico et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2023b). Late Eocene cooling likely increased primary productivity at low latitudes (Rodrigues de Faria et al., 2024), whereas marginal environments experienced nutrient fluxes from terrestrial to marine systems, contributing to transient CO2 release (De Lira Mota et al., 2023). These changes led to a turnover in marine ecosystems, including shifts in communities of calcareous nannofossils and foraminifera (Coxall and Pearson, 2007). Specific taxa, such Discoaster barbadiensis, Discoaster saipanensis, and Reticulofenestra reticulata, went extinct, likely due to cooling and nutrient seasonality (Aubry, 1992; Bordiga et al., 2015), while planktonic foraminifera experienced a reduced biodiversity, with eight species going extinct near the Eocene–Oligocene boundary (EOB) (Wade and Pearson, 2008). Benthic foraminifera also declined in diversity, including a decrease in the abundances of rectilinear forms with complex apertures (Bordiga et al., 2015), which had become more abundant since the Paleocene, reaching their maximum percentages during the late Eocene (Alegret et al., 2021). Declines in agglutinated benthic foraminifera, often linked to CCD deepening, have been documented at site-specific locations such as ODP Site 647 (Kaminski and Ortiz, 2014); Portella Colla, Sicily (Benedetti, 2017); and the Carpatians (van Couvering et al., 1981), where the agglutinated abundance dropped at the EOT. However, global compilations (Alegret et al., 2021) suggest that agglutinated assemblages remained relatively stable across major ocean basins.

Globally, the EOT was characterized by a significant reorganization of ocean circulation, deep-sea oxygenation, remineralization rates, and the size of the carbon reservoir, ultimately reshaping phytoplankton communities and benthic foraminiferal assemblages (Alegret et al., 2021; Hutchinson et al., 2021). Although studies from mid- to high-latitude sites indicate a shift toward more oligotrophic, seasonally pulsed deep-sea ecosystems, the applicability of these patterns to tropical regions, such as the southwestern Caribbean, remains unclear.

The impacts of the EOT have been extensively documented in several terrestrial and marine ecosystems worldwide (Boersma, 1986; Aubry, 1992; Prothero and Berggren, 1992; Prothero et al., 2003; Coxall et al., 2005; Coxall and Pearson, 2007; Thomas, 2007; Kraatz and Geisler, 2010; Houben et al., 2012; Ozsvárt et al., 2016; Su et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2020; Hutchinson et al., 2021; De Lira Mota et al., 2023), but the tropical Caribbean remains understudied. Limited evidence suggests reduced palynofloral diversity (Jaramillo et al., 2006), a replacement of Pelliciera mangroves by Rhizophora (Rull, 2023), and the staggered extinction of larger benthic foraminifera on the Nicaraguan carbonate shelf (Robinson, 2003). These findings indicate significant ecosystem changes but leave many open questions about the region's response to global climatic shifts.

The Caribbean region of northwestern South America played a key role in connecting the Pacific and Atlantic water masses through the Central American Seaway (CAS), which influenced global ocean circulation, nutrient exchange, and marine biodiversity (Duque-Caro, 1990; Haug and Tiedemann, 1998; Haug et al. 2001; Iturralde-Vinent, 2006; Jain and Collins, 2007; O'Dea et al., 2016; Jaramillo, 2018; Vallejo-Hincapié et al., 2024). Despite its status as a marine biodiversity hotspot (Miloslavich et al., 2010), the paleoecological and paleoenvironmental evolution of the region during the Paleogene remains poorly understood. Late Paleogene sedimentation reflects a transgressive setting influenced by tectonic subsidence in the Colombian Caribbean region (Mora-Bohórquez et al., 2017, 2018, 2020; Celis et al., 2023, 2024). The ANH-SAN JACINTO-1 (hereafter referred to as ANH-SJ-1; Fig. 1) drill core provides a near-continuous marine record from the upper Eocene to the lower Miocene, encompassing the EOB (Arias-Villegas et al., 2023; Trejos-Tamayo et al., 2025a), and thus offers a unique opportunity to unravel ecosystem dynamics during this critical transition and evaluate whether tropical responses diverged from the combined effects of global cooling, Antarctic glaciation, and pCO2 drawdown.

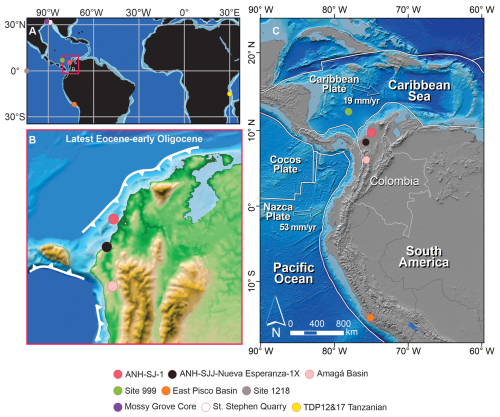

Figure 1Geographic and paleogeographic location of the ANH-SJ-1 drill core in the Caribbean region of NW South America. (A) Late Eocene (∼ 34 Ma) paleogeographic reconstruction, generated using the Plate Tectonic Reconstruction Service of the Ocean Drilling Stratigraphic Network (http://www.odsn.de, last access: 6 January 2025) and modified based on reconstructions for the Caribbean by Iturralde-Vinent and MacPhee (1999), Pindell et al. (2006), Pindell and Kennan (2009), and Montes et al. (2021). (B) Paleogeographic reconstruction of NW South America during the late Eocene to early Oligocene, modified from Moreno-Sánchez and Pardo-Trujillo (2003), Scotese and Wright (2018), and Montes et al. (2021). (C) Regional tectonic framework of the NW South America region (Colombia), illustrating the relative motion of the Caribbean, Nazca, and Cocos plates. Plate velocities are indicated in millimeters per year (mm yr−1). The maps show the location of the ANH-SJ-1 core along with other key study sites mentioned in the discussion, including ODP Site 999 in the SW Caribbean (Sigurdsson et al., 1997), the ANH-SJJ-Nueva Esperanza-1X (Celis et al., 2023) and the Amagá Basin in NW South America (Celis et al., 2023; Pardo-Trujillo et al., 2023), the East Pisco Basin in Peru (Malinverno et al., 2021), Site 1218 in the eastern equatorial Pacific (Taylor et al., 2023a, b), St. Stephen Quarry (Miller et al., 2008) and Mossy Grove Core (De Lira Mota et al., 2023) in the Gulf of Mexico, and TDP Sites 12 and 17 in Tanzania (Dunkley Jones et al., 2008).

This study represents the first systematic analysis of EOT sediments from this region, integrating palynological, calcareous nannofossil, foraminiferal, XRF, and δ13C data from the ANH-SJ-1 drill core. We aim to assess how tropical marine ecosystems in the southwestern Caribbean responded to global environmental changes during the EOT. We hypothesize that this region underwent significant ecological and geochemical shifts, including the reorganization of marine communities, increased terrigenous input, and enhanced carbonate preservation, reflecting its strong sensitivity to global climate forcing.

To evaluate this, we assess the timing, nature, and persistence of these changes by comparing key intervals: pre-EOT (∼ 36–34.4 Ma), EOT (∼ 34.4–33.4 Ma), and post-EOT (∼ 33.4–32 Ma), as well as the upper Eocene and lower Oligocene. Our analysis focuses on four main objectives: (1) to determine whether a sea-level fall occurred in NW South America, (2) to reconstruct changes in surface productivity, (3) to assess shifts in bottom-water oxygenation and carbonate preservation, and (4) to evaluate the influence of terrigenous input and freshwater dynamics on depositional environments.

2.1 Site location and sampling

Core ANH-SJ-1 (9°48′5.47′′ N, 75°7′33.95′′ W) was drilled in 2015 by the Colombian National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH) in NW Colombia, approximately 55 km from the Caribbean coast (Fig. 1). The core and all micropaleontological materials are permanently curated at the National Core Repository of the Colombian Geological Service (Piedecuesta, Santander), as part of the ANH project under contract FP44842-494-2017 and the Special Cooperation Agreement 730/327-2016. Sampling for micropaleontological analyses was conducted in 2018. All slide and sample identifiers used in this study are listed in Tables S1–S4 in the Supplement and are cross-referenced in the Zenodo record, which includes the complete supplementary dataset (tables and figures) (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17330356, Trejos-Tamayo et al., 2025b). Since the core was obtained from exploratory petroleum drilling, the sample volume was limited, which required a careful selection of analytical methods based on material availability. Biostratigraphic data based on calcareous nannofossils and palynology have recently been published by Arias-Villegas et al. (2023) and Pardo-Trujillo et al. (2023), while paleoenvironmental interpretations based on benthic foraminifera indicate water depths exceeding 1000 m during the late Eocene to early Oligocene (Trejos-Tamayo et al., 2024, 2025a).

The core reached a maximum depth of 524 m; however, due to the dip angle of the beds (40—60°), a corrected thickness of 342 m was calculated using simple trigonometric methods (Arias-Villegas et al., 2023). It encompasses a marine sequence spanning the upper Eocene to lower Miocene, with unconformities identified in the upper Eocene, lower Oligocene, and upper Oligocene to lower Miocene intervals (Arias-Villegas et al., 2023). However, the specific interval analyzed in this study (178.6–302.2 m) is continuous and unaffected by hiatuses, providing a reliable archive across the EOT. This study focuses on the 124 m section, which corresponds to the upper Eocene–lower Oligocene interval (Fig. 2). This sedimentary succession comprises massive or parallel-laminated black to brownish-gray calcareous mudstones and siltstones, both of which are frequently bioturbated (e.g., Chondrites, Palaeophycus, Taenidium, and Thalassinoides).

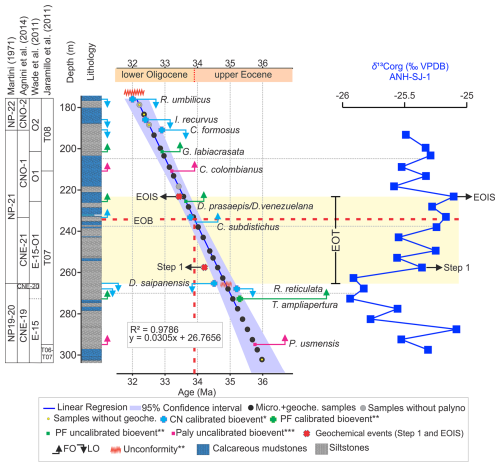

Figure 2Age model for the upper Eocene to lower Oligocene interval of the ANH-SJ-1 drill core. Calibration is based on biostratigraphic tie points from calcareous nannofossils (Arias-Villegas et al., 2023, *), planktonic foraminifera (this study, ), and palynology (Pardo-Trujillo et al., 2023, ). The figure displays the linear regression used to calculate sample ages (R2=0.98), along with its 95 % confidence interval. Biozones are shown for calcareous nannofossils (after Arias-Villegas et al., 2023), planktonic foraminifera (Wade et al., 2011), and palynology (Jaramillo et al., 2011), along with the lithological composition of the interval. First and last occurrences (FOs and LOs) of key taxa used as age markers are also indicated. Bulk δ13Corg values (blue curve) show two positive excursions: one at ∼ 258 m (∼ 34.2 Ma), corresponding to Step 1 of the carbon isotope excursion, and another at ∼ 223.2 m (∼ 33.7 Ma), which coincides with the Earliest Oligocene Oxygen Isotope Step (EOIS). Both excursions closely align with the global benthic δ13C curve from Westerhold et al. (2020). For a detailed comparison between our δ13Corg record and the global benthic δ13C curve from Westerhold et al. (2020), see also Fig. S1 in the Supplement. Together with the extinction of D. saipanensis at 265.3 m (∼ 34.4 Ma), these features constrain the EOT in the ANH-SJ-1 core. Chronostratigraphy follows Gradstein et al. (2020). Abbreviations: CN – calcareous nannofossils, PF – planktonic foraminifera, Paly – palynology, Micro – microfossils (CN, PF, and palynology), Geoche. – geochemistry.

2.2 Age model definition for the ANH-SJ-1 core

To construct the age model for the ANH-SJ-1 core, we integrated multiple biostratigraphic and geochemical datasets. Biochronological information was derived from calcareous nannofossils (Arias-Villegas et al., 2023), planktonic foraminiferal bioevents identified in this study, and palynological data (Pardo-Trujillo et al., 2023). Additionally, δ13C isotope data obtained from the core were correlated with the global benthic carbon isotope reference curve of Westerhold et al. (2020), as shown in the Supplement (Fig. S1).

A set of biostratigraphic tie points was defined based on the first and last occurrences of key taxa using published age calibrations (e.g., Agnini et al., 2014; Wade et al., 2011; Jaramillo et al., 2011). These tie points, including the depths and corresponding ages, are detailed in Table 1.

Linear regression was applied to the calibrated tie points using Python's scikit-learn library (Pedregosa et al., 2011) to generate a depth–age model for the interval spanning the late Eocene to early Oligocene. The resulting model integrates calcareous nannofossil and foraminiferal events as primary age anchors, with additional support from palynological zonations and δ13C trends.

2.3 Micropaleontology

A total of 26 samples were collected across the study section at ∼ 8.5 m intervals for palynological, calcareous nannofossil, and foraminiferal analyses. All samples were analyzed for calcareous nannofossils and foraminifera, while only 23 samples were analyzed for palynology due to insufficient material (Table S1). The nannofossil samples were previously studied by Arias-Villegas et al. (2023). This study includes additional palynological and benthic foraminiferal data not presented by Pardo-Trujillo et al. (2023) and Trejos-Tamayo et al. (2024), respectively. Sample preparations and analysis were conducted at the calcareous microfossils and organic matter laboratories of the Instituto de Investigaciones en Estratigrafía (IIES), Universidad de Caldas (Colombia).

2.3.1 Palynology

Sample preparation for palynology followed the standard procedure of Traverse (2007). Approximately 20 g of rock was cleaned and crushed to obtain fragments of 1–2 mm. Carbonates were removed using 50 mL of 37 % hydrochloric (HCl) acid, and silicates were dissolved in 70 % hydrofluoric (HF) acid, followed by washing and filtration through 100 µm and 10 µm mesh sieves. Samples were placed in an ultrasonic bath for ∼ 1 min to disaggregate any remaining mineral particles adhering to the organic residue. In some cases, this step caused fragmentation of large aggregates. The resulting suspension was re-filtered through a 10 µm mesh to recover the cleaned palynological fraction. Humic acids were removed by adding 10 % potassium hydroxide (KOH) to the sample, and the resulting mixture was centrifuged to concentrate the organic residue.

The recovered organic matter was divided into two subsamples: oxidized and unoxidized. One subsample was oxidized using a brief and controlled treatment with 65 % nitric acid (HNO3) to reduce amorphous organic material, followed by 5 % ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) to remove residual humic substances. This treatment did not compromise the preservation of dinoflagellate cysts. The unoxidized fraction was processed in parallel to preserve more delicate structures and confirm assemblage integrity. The oxidized material was filtered through a 10 µm mesh, and the organic film was mounted on a coverslip, fixed onto slides, and sealed with Canada balsam. Palynomorph identification, counting, and description were performed using a Nikon 80i transmitted light microscope with 40× and 100× objectives. Taxonomic identification was based on several regional references (e.g., Germeraad et al., 1968; Lorente, 1986; Muller et al., 1987; Hoorn, 1993; Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001; Plata-Torres et al., 2024) and the morphological database of Jaramillo and Rueda (2024).

Due to the low and variable abundances of palynomorphs, all specimens were counted and identified, with the complete species list presented in Table S1. For visualization, only the most abundant taxa are shown in Fig. S2. To assess the composition and behavior of palynological assemblages over the interval, diversity indices such as Shannon (H′) and Chao1, as well as dominance (D), were calculated using Past 4.08 software (Hammer et al., 2001). The terrestrialmarine index ( index), based on the relative proportions of terrestrial (spores and pollen) and marine palynomorphs (dinoflagellate cysts, scolecodonts, and foraminiferal organic linings), was used to reconstruct transgression–regression processes and regional sea-level changes in marine facies without direct links to coastal records (Peeters et al., 1998; Prauss, 2001; Olde et al., 2015). The index used in this study was calculated as the proportion of marine palynomorphs relative to the total sum of marine and terrestrial palynomorphs ( = Marine [Marine + Terrestrial]), with higher values indicating greater marine influence. Variations in dinoflagellate species richness were also used to infer changes in sea level. In this lower bathyal setting (>1000 m water depth; Trejos-Tamayo et al., 2024, 2025a), increased richness is interpreted as a response to elevated surface productivity, likely driven by enhanced terrigenous nutrient input during sea-level highstand rather than a direct consequence of expanded shelf areas (Olde et al., 2015). Terrestrial palynological components were included to provide insights into the composition of the tropical flora (Table S1).

2.3.2 Calcareous nannofossils

Slides for calcareous nannofossils were prepared using the standard smear-slide method, as described by Bown and Young (1998), at the IIES of the Universidad de Caldas. Taxonomic identification was conducted at ×1000 magnification using a Nikon Eclipse petrographic microscope. Quantitative analyses were performed by examining 10 transects or counting up to 300 individuals per slide whenever possible. Absolute abundances (i.e., total coccoliths) were used as a quantitative proxy for nannofossil productivity, following Jiang and Wise (2009).

Preservation was assessed according to the criteria of Roth and Thierstein (1972). Poor preservation (1) is characterized by high levels of dissolution and/or recrystallization, resulting in significant modification of diagnostic features. Moderate preservation (2) features some dissolution and/or recrystallization, with minor alteration of diagnostic features. Good preservation (3) is marked by minimal dissolution and/or recrystallization, with clear and intact specimen morphology. The taxonomic methodology is detailed in Arias-Villegas et al. (2023), with the filtered species list provided in the Supplement (Table S2).

Key bioevents, selected from Table 1 of Arias-Villegas et al. (2023), were calibrated using markers for Paleogene mid- to low-latitude deposits (e.g., Backman, 1987; Blaj et al., 2009; Fioroni et al., 2012; Agnini et al., 2014). These bioevents are consistent with the standard biozonation schemes established by Martini (1971), Backman (1987), and Agnini et al. (2014).

The Shannon (H′) and Chao1 diversity indices and dominance (D) were calculated for all samples. To interpret paleoenvironmental conditions, we identified taxa sensitive to temperature and trophic changes as indicators (Tables S5 and S6). Additionally, a temperature index (IT°) and a trophic index (Iτ) were constructed according to the criteria of Villa et al. (2008) and the paleoenvironmental index of Cappelli et al. (2019), respectively. The IT° is defined as IT° = %warm taxa (%cold taxa + %temperate taxa + %warm taxa). Values close to 0 indicate environments with a higher abundance of temperate and even cold taxa, while values close to 1 are associated with warm taxa. The Iτ is defined as Iτ = %eutrophic taxa (%eutrophic taxa + %mesotrophic taxa + %oligotrophic taxa). Values close to 0 indicate environments with a higher abundance of oligotrophic and mesotrophic taxa, while values close to 1 are associated with higher abundances of eutrophic taxa. For visualization, some major taxa are shown in Fig. S3.

2.3.3 Planktonic and benthic foraminifera

For planktonic and benthic foraminifera, approximately 30 g of rock per sample was disaggregated in water containing 5 % hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), washed through a 63 µm sieve, and dried at 45 °C for 48 h. The dried residue was then sieved using a 125 µm mesh for benthic foraminifera and a 150 µm mesh for planktonic foraminifera. Due to low abundances, all foraminifera specimens in the 125 and 150 µm fractions were extracted and analyzed. Foraminiferal specimens were examined using Nikon SMZ745 and SMZ1500 binocular stereoscopes. The state of preservation of planktonic and benthic foraminifera was assessed according to the criteria of Pälike et al. (2010), which we adapted by assigning numerical values to facilitate graphical representation: poor (1), characterized by significant overgrowth, dissolution, or fragmentation; moderate (2), minor but common occurrences of calcite overgrowth, dissolution, or abrasion; and good (3), minimal evidence of overgrowth, dissolution, or abrasion.

Identification of planktonic foraminifera followed the criteria of Pearson et al. (2006) and Wade et al. (2018), while benthic foraminifera were identified according to van Morkhoven et al. (1986), Loeblich and Tappan (1987), Bolli et al. (1994), Jones (1994), Kaminski and Gradstein (2005), and Holbourn et al. (2013). Tables S3 and S4 contain the counts of planktonic and benthic foraminiferal assemblages. Although the number of specimens per sample was often low, ecological trends in benthic assemblages were interpreted using a combination of qualitative observations and statistical indices (see Sect. 2.4 for methodological details). H′, Chao1, and D indices were calculated using Past 4.08 software. Planktonic foraminifera were primarily used for biostratigraphy using the biozone scheme of Wade et al. (2011) to complement the existing nannofossil-based age model. Ages were estimated from Wade et al. (2011, 2018).

To assess bottom-water paleoenvironmental conditions, including oxygenation, nutrient availability, and calcium carbonate preservation, we applied the enhanced benthic foraminifera oxygenation index (EBFOI) of Kranner et al. (2022). For this index, benthic foraminifera were categorized into oxic, suboxic, and dysoxic groups (Table S4), following the classifications of Mackensen and Douglas (1989), Kaiho (1994), Sen Gupta and Machain-Castillo (1993), Schumacher et al. (2007), Kaminski (2012), and Kranner et al. (2022). Although the study material was limited, with total specimen counts relatively low in most intervals (<100 individuals), we calculated the EBFOI while carefully considering these limitations and focused the interpretation on relative patterns rather than absolute oxygen concentrations. Additional proxies (e.g., infaunal epifaunal ratio, , and foraminiferal preservation) were integrated to strengthen the paleoenvironmental interpretations. EBFOI values between 50 and 100 indicate high oxygen levels, while values below 50 indicate low oxygen levels. Additionally, oxygen (O2) concentrations were estimated using Tetard et al. (2021): oxic O2 > 1.5 mL, suboxic O2 between 0.5 and 1.5 mL, and dysoxic O2 < 0.5 mL. The distribution of benthic foraminifera was further analyzed based on shell composition (agglutinated, hyaline, and porcelain) and infaunal vs. epifaunal proportions.

Despite the low and variable specimen counts in some samples, the indices applied (e.g., EBFOI, H′, Chao1) are based on relative abundances and remain informative. Still, their interpretation should be approached cautiously due to potential sampling and preservation biases. For visualization, some major benthic foraminifera taxa are shown in Fig. S4.

2.4 Geochemical analysis

A total of 22 bulk samples were analyzed for XRF and carbon isotopes (δ13C). However, only 11 were analyzed for total carbon (TC) and total inorganic carbon (TIC) due to insufficient sediment availability.

2.4.1 XRF analysis

XRF analyses were conducted to examine variations in the elemental composition of the sediments and provide insights into terrigenous and biological inputs, as well as environmental changes. The samples were ground to particle sizes of 0–500 µm using an agate mortar and transferred to 40 mm sample cups. Analyses were performed at the EMSO-GOLD Laboratory at the Portuguese Institute of the Sea and Atmosphere (DivGM-IPMA) using an Avaatech fourth-generation XRF core scanner (https://www.avaatech.com/, last access: 16 January 2025).

Scanning was done at 10, 30, and 50 kV, with currents of 200, 250, and 1000 µA, respectively. Parameters such as throughput (regulating signal flow to prevent detector overload) and area count (intensity measurement at each analysis point) were optimized to increase accuracy and efficiency. Detected data were normalized via throughput corrections to account for signal flow variability, ensuring consistent quantification of elements. Real-time (total acquisition time) and live time (effective detection time) were distinguished, and acquisition time at each position was adjusted to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio. Data were processed using BRIGHTSPEC bAxil software.

To further explore the structure of the dataset and support the interpretation of sediment sources, we applied a principal component analysis (PCA) to identify elemental loading patterns (Table S7; Fig. S5). This multivariate approach helped distinguish elements associated with biogenic inputs (e.g., Ca, Sr) from those linked to terrigenous sources (e.g., Ti, Al, Fe, K), thereby supporting the use of specific ratios as environmental proxies. Although log ratios are often recommended for XRF data obtained from core surface scans, they were not applied here because the scanner was used on homogenized, powdered discrete samples – not intact cores. Elemental intensities were internally normalized via throughput correction, ensuring consistency across measurements and making additional log transformation unnecessary. This methodological detail has been clarified to avoid confusion regarding data processing and comparability.

Based on the elemental data (Table S8), key geochemical ratios were calculated to interpret sedimentary and environmental processes. These include , , and as indicators of sediment grain size and aeolian inputs (Boyle, 1983; Dypvik and Harris, 2001; Kylander et al., 2011; Heymann et al., 2013); and as proxies for biogenic calcium carbonate production and detrital inputs (Bayon et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2023; Lear et al., 2003); as an indicator of weathering intensity (Hu et al., 2012; Bosq et al., 2020; Matys Grygar et al., 2020); and as a proxy for organic matter fluxes to the seafloor (Lowery and Bralower, 2022).

2.4.2 Carbon isotopes and carbon content

Total carbon (TC) and total inorganic carbon (TIC) were analyzed in bulk sediments. TC was measured by combustion using a Carlo Erba NA 1500 CNS elemental analyzer, while TIC was determined via acidification and coulometric titration (AutoMate Prep Device, UIC 5017 CO2 coulometer). Total organic carbon (TOC) was calculated as TOC = TC − TIC. Bulk sediment was pretreated with 2 N HCl to remove carbonate, and stable carbon isotope ratios (δ13Corg) were measured on the carbonate-free portion using a Carlo Erba NA 1500 CNS elemental analyzer coupled with a Thermo Electron DeltaV Advantage isotope ratio mass spectrometer. Carbon isotope data are expressed relative to VPDB in ‰. Carbonate loss provides valuable information on the availability of carbonates in the samples.

2.5 Statistical procedures

Our primary goal was to understand the ecological and geochemical changes that occurred across the EOT. To achieve this, we analyzed environmental and biological proxies using both two- and three-phase temporal subdivisions. The two-phase scheme compared the upper Eocene (∼ 36–33.9 Ma) and lower Oligocene (∼ 33.9–32 Ma) intervals (Tables S9 and S10; Fig. S6), while the three-phase approach distinguished between pre-EOT (302.2–267.8 m; n=8, ∼ 36–34.9 Ma), EOT (262.7–223.2 m; n=9), and post-EOT (218.3–178.6 m; n=9, ∼ 33.4–32.2 Ma) intervals (Tables S11 and S12; Fig. S7).

These subdivisions were initially defined based on standard chronostratigraphic boundaries reported in the literature (e.g., Hutchinson et al., 2021) and adapted to our record using our age model (see Sect. 4.1). To assess whether these divisions also reflect natural ecological structuring, we performed constrained hierarchical clustering (CONISS) on calcareous nannofossil, palynological, and benthic foraminiferal assemblages (Figs. S2, S3, and S4). The results revealed ecological breaks that broadly correspond to the biochronologically defined pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT intervals, thereby supporting their use as robust units for statistical and paleoenvironmental comparison.

Statistical analyses were performed using Python 3.13.0, employing the SciPy library for Shapiro–Wilk and Kruskal–Wallis tests, as well as for ANOVA and pairwise t tests. Data normalization and manipulation were performed using Pandas, with min–max scaling applied via scikit-learn. Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for non-parametric comparisons between upper Eocene and lower Oligocene assemblages, while ANOVA was applied to the three-segment framework after normalization. Where significant differences were found, pairwise comparisons were evaluated using t tests. All visualizations were generated with Matplotlib and Seaborn.

Although specific proxies, particularly foraminiferal assemblages, exhibited low and variable specimen counts in some samples, the use of diversity and dominance indices (e.g., Shannon H′, Chao1, dominance D) is well established in micropaleontological studies with limited material (Chao, 1984; Magurran, 2004; Hammer et al., 2001). Non-parametric tests were specifically chosen for their robustness in handling small sample sizes and non-normal data distributions. Furthermore, the EBFOI was used based on the proportional representation of ecological groups rather than absolute counts, making it appropriate even under low-abundance conditions (Kranner et al., 2022).

In cases where statistical power may be constrained, results were interpreted cautiously and supported by qualitative observations and independent geochemical or sedimentological proxies. This combined approach allowed for the detection of meaningful ecological trends while accounting for the inherent limitations of sample availability and fossil preservation.

3.1 Age model and biostratigraphic framework

Our age model integration establishes a robust biostratigraphic framework for the upper Eocene to lower Oligocene interval (Fig. 2; Table 1). The sedimentary succession spans the NP19–20 to NP22 calcareous nannofossil biozones of Martini (1971) and the CNE19 to CNO2 biozones of Agnini et al. (2014) from the first occurrence (FO) of Reticulofenestra reticulata at 270.2 m (35.2 Ma) to the last occurrence (LO) of R. umbilicus at 176 m (32 Ma; Table 1, Fig. 2).

Planktonic foraminiferal bioevents are consistent with the calcareous nannofossil age model. For instance, the FO of Turborotalia ampliapertura at 275.2 m, dated to 35.3 Ma (Berggren and Pearson, 2005), closely matches the overlying LO of R. reticulata (Table 1; Fig. 2). However, the low abundance and preservation of planktonic foraminifera between ∼ 268 and ∼ 228 m posed challenges for precisely defining the upper Eocene–lower Oligocene boundary. Nevertheless, the FOs of Dentoglobigerina prasaepis and Dentoglobigerina venezuelana at 225.7 m indicate the presence of the O1 biozone of Wade et al. (2011), while the FO of Globoturborotalita labiacrasata at 201.4 m marks the beginning of the O2 biozone (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Palynological biozones T07 and T08, identified following Jaramillo et al. (2011), are based on the FO of Polypodiisporites usmensis at ∼ 295 m and Crassiectoapertites columbianus at ∼ 211 m. The maximum likelihood method (Punyasena et al., 2012), applied to palynofloral assemblages, provides independent probability distributions for age assignments, illustrating the range of uncertainties associated with biostratigraphic correlation and supporting the temporal placement of palynological zones (Table S13, Fig. S8).

Linear regression analysis between calibrated ages and corrected core depths yielded a strong fit (R2=0.98). Age uncertainties range from ±0.20 to ±0.47 Ma and are based on the residuals of the regression model applied to the biostratigraphic and isotopic tie points. This age–depth relationship was subsequently used to interpolate ages for levels without direct age markers (Table S14). Notably, the δ13C record shows two prominent positive excursions at ∼ 258 and ∼ 223 m, which closely match the global benthic carbon isotope events known as Step 1 (∼ 34.2 Ma) and the Earliest Oligocene Oxygen Isotope Step (EOIS; ∼ 33.7 Ma), respectively (Coxall and Pearson, 2007; Speijer et al., 2020; Hutchinson et al., 2021). The strong agreement between our δ13C curve and the global stack of Westerhold et al. (2020), as illustrated in Fig. S1, reinforces the reliability of our age model. In conjunction with the extinction of Discoaster saipanensis at 265.3 m (dated at ∼ 34.4 Ma), these isotopic markers constrain the EOT interval in core ANH-SJ-1 to between 265.3 and 223.2 m depth.

Based on the integration of multiple biostratigraphic indicators, a robust age–depth regression model, and a clearly expressed δ13C signal corresponding to the EOIS event, we define the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT intervals used throughout the analyses. These intervals provide a stratigraphically and geochemically supported framework for evaluating paleoenvironmental change across the transition.

Notably, these time intervals align closely with shifts in microfossil assemblages identified through stratigraphically constrained cluster analyses (CONISS; Figs. S2–S4). The ecological groupings revealed by these dendrograms (indicated by dashed lines) change near the chronostratigraphic boundaries defined for the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT intervals. This correspondence provides independent, ecologically grounded support for the chosen divisions, thereby increasing our confidence that the statistical comparisons accurately reflect meaningful paleoenvironmental transitions rather than arbitrary sample grouping.

More specifically, the onset of the EOT is associated with transitions from group P1 to P2 in palynology, from N1b to N2a in calcareous nannofossils, and from F2a to F2b in benthic foraminifera (Figs. S2–S4). Similarly, the end of the EOT corresponds to shifts from group P3b to P3c, N2b to N2c, and F2d to F3, respectively. These transitions, which occur close to the biostratigraphically constrained EOT boundaries, reinforce the interpretive robustness of our multiproxy framework.

Arias-Villegas et al. (2023) suggested a possible hiatus between the LO of R. reticulata at 270.2 m and the LO of D. saipanensis at 265.3 m; however, our model suggests that any such gap is likely confined within sampling resolution. The EOB is inferred at ∼ 238 m based on the alignment between the regression-derived age model and a distinct positive δ13C excursion at that depth, which correlates with the EOIS. The integration of stratigraphic depth and isotopic data enables more precise placement of the EOB within the core. Despite the limited resolution of 26 samples, our dataset aligns with global events, reinforcing the reliability of the ANH-SJ-1 age model (Fig. 2). The relatively high stratigraphic position of the LO of R. reticulata in ANH-SJ-1 is consistent with tropical records from Java, where this event is also recorded close to the Discoaster extinction event, a rapid extinction of rosette-shaped Discoaster species at ∼ 34.44 Ma that marks the onset of significant biotic and environmental change at the start of the EOT (Jones et al., 2019).

Although the regression model demonstrates strong reliability (R2=0.98, accounting for nearly 98 % of the variability), a notable discrepancy exists between the expected depth of 34.4 Ma based on the regression line (249.5 m) and the observed extinction of D. saipanensis at 265.3 m. This is because the regression model was constructed using a combination of independent biostratigraphic markers, including both literature-based calibrations and locally observed bioevents, but did not assign a fixed age of 34.4 Ma to the D. saipanensis event. Therefore, the offset likely reflects localized variability in sedimentation rates, compaction, or preservation not captured by the linear model. Given the global significance of the LO of D. saipanensis as a marker for the onset of the EOT, we prioritize its observed depth (265.3 m) as the stratigraphic reference for this transition.

The regression model likely represents an averaged depth–age relationship across the core; however, local deviations, such as the possible hiatus proposed by Arias-Villegas et al. (2023), could explain this discrepancy. By prioritizing the extinction of D. saipanensis at 265.3 m as the primary marker while acknowledging the regression-predicted depth of 249.5 m for 34.4 Ma, we balance the high precision of the model with the critical biostratigraphic evidence needed for global correlations.

Table 1Microfossil bioevents for the upper Eocene to lower Oligocene interval in the ANH-SJ-1 drill core. Events marked with “a” correspond to calcareous nannofossil bioevents reported by Arias-Villegas et al. (2023); those marked with “b” indicate palynological events identified by Pardo-Trujillo et al. (2023). All depths are corrected for core recovery. Bioevent abbreviations: CN – calcareous nannofossil, F – foraminifera, P – palynology.

3.2 Palynology

The average palynomorph abundance per sample is 81 individuals (Fig. S9). Statistical analyses reveal that palynomorph abundances show no significant variability between the upper Eocene and lower Oligocene (Kruskal–Wallis (K–W) p=0.63) or among the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT periods (ANOVA p=0.53). Diversity indices (H′ and Chao1) display contrasting trends: H′ averages 2.4 and remains stable across the EOT (K–W p=0.9; ANOVA p=0.4; Figs. S6, S7, and S9). Conversely, Chao1 richness decreases to minimum values (<10) during the EOT and recovers to values above 20 in the lower Oligocene (K–W p=0.94; ANOVA p=0.87).

Dominance values average 0.13, with peaks (>0.2) between 249.5 and 228.1 m, corresponding to assemblages dominated by dinoflagellates (Spiniferites spp.), foraminiferal organic linings, fungi, and spores, including Cicatricosisporites dorogensis, Laevigatosporites spp., and Polypodiisporites spp. (Fig. S2). Statistical tests show no significant difference in dominance values between the upper Eocene and lower Oligocene (K–W p=0.13). However, dominance shows significant variation among the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT intervals (ANOVA p=0.04).

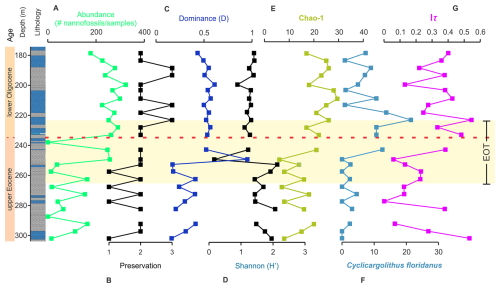

Figure 3Temporal and stratigraphic evolution of palynological variables showing statistically significant patterns across the upper Eocene–lower Oligocene interval in the ANH-SJ-1 drill core. Panels display the relative abundances of (A) pollen, (B) spores, and (C) the terrestrialmarine () index.

Spores, the most abundant palynomorph group (12 %–73 %), exhibit slight variability in abundance across the EOT (K–W p=0.097; ANOVA p=0.7). Their highest concentrations (60 %–73 %) occur between 243 and 213.2 m (Fig. 3). Pollen abundances range from 9 % to 58 %, peaking in the upper Eocene (>50 %) between 297.5 and 257.6 m but consistently falling below 25 % in the lower Oligocene. Statistical tests show significant differences in the relative abundance of pollen between the upper Eocene and lower Oligocene (K–W p=0.04) but no significant changes among the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT periods (ANOVA p=0.7).

Dinoflagellate abundances exhibit two peaks: one in the upper Eocene (262.7–249.5 m) and another in the lower Oligocene (208.9–199.6 m). Statistical analyses indicate no significant variability between the upper Eocene and lower Oligocene (K–W p=0.257) and across the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT periods (ANOVA p=0.7). Foraminiferal organic linings are abundant (∼ 40 %) at the beginning of the study interval (302.2–292.5 m), declining sharply and stabilizing at 11 %–5 % thereafter (K–W p=0.04; ANOVA p=0.16).

The index ranges from 1.8 to 1.1 in the upper Eocene, with lower Oligocene values averaging 1.1. Peaks exceeding 2 at 208.9 and 199.6 m reflect transient increases in marine influence (Fig. 3). Statistical tests reveal marginal variability in index values between the upper Eocene and lower Oligocene (K–W p=0.06) and no significant differences across the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT intervals (ANOVA p=0.3). While these intervals are based on a robust, multiproxy age model, we acknowledge that they may not fully capture the finer-scale oscillations observed in the raw signal, such as the marked peaks at 208.9 and 199.6 m. This applies more broadly to other environmental proxies as well, where predefined intervals support statistical comparison but may smooth over short-term paleoenvironmental fluctuations that are evident in the stratigraphic trends.

3.3 Calcareous nannofossils

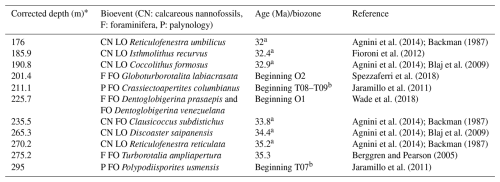

Absolute abundances of calcareous nannofossils exhibit temporal variation, averaging 71 individuals per sample between 302.2 and 252.9 m and increasing to ∼ 259 individuals per sample from 249.5 to 178.6 m (K–W p=0.0004; ANOVA p=0.0002; Fig. 4A; Arias-Villegas et al., 2023). Preservation improves over time, transitioning from poor to moderate between 302.2 and 228.1 m and from moderate to good between 223.2 and 178.6 m (Fig. 4B). Diversity indices show notable trends: H′ averages 1.6 in the upper Eocene and decreases to 1.3 in the lower Oligocene (K–W p=0.06; ANOVA p=0.2; Fig. 4C–E). Chao1 richness starts below 20 between 302.2 and 249.5 m, reflecting low richness during this interval, and increases to values above 20 from 243 m onward, peaking in the lower Oligocene (K–W p=0.0003; ANOVA p=0.0003). Dominance increases from values below 0.5 in the upper Eocene to peaks above 0.5 in the Oligocene, often associated with taxa such as Coccolithus pelagicus, Cyclicargolithus floridanus, Reticulofenestra bisecta, R. dictyoda, and R. locker (Fig. S3; Table S2).

Figure 4Temporal and depth evolution of calcareous nannofossil parameters in the ANH-SJ-1 drill core. The vertical axis represents time in Ma and the core lithology (depth in meters). Panel (A) shows the absolute abundance of nannofossils, while (B) shows the preservation index. Panel (C) shows the dominance index (D), and panels (D) and (E) show the Shannon (H′) and Chao1 diversity indices. Panels (F) and (G) show the relative abundance of Cyclicargolithus floridanus and the trophic index (Iτ), respectively. These indices reflect significant or near-significant trends in the Kruskal–Wallis (K–W) and ANOVA tests. The dashed red line indicates the EOB.

Temperate species dominate temperature-sensitive taxa throughout the interval (Fig. S10). Warm taxa exhibit periodic peaks, indicating transient warming events at 267.8, 252.9, 213.2, and 188.5 m (Fig. S10). Cold-water taxa are rare, peaking at 14 % at 292.5 m and declining to <0.5 % during the Oligocene. Temperature indices do not show significant variation between the Eocene and Oligocene (K–W p=0.4; ANOVA p=0.8) or across the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT periods (ANOVA p=0.7; Figs. S6 and S7).

The trophic index (Iτ) gradually increases throughout the study interval. In the upper Eocene, Iτ averages 0.29, reflecting lower trophic conditions. From 243 m onward, Iτ increases, peaking above 0.4 between 233.1 and 208.9 m (K–W p=0.1; ANOVA p=0.03; Fig. 4G). This trend coincides with an increase in eutrophic taxa, particularly C. floridanus, a species indicative of upwelling, which becomes more abundant after 243 m, reaching its highest abundance at 223.2 m (ANOVA p=0.04; Fig. 4F).

3.4 Foraminifera

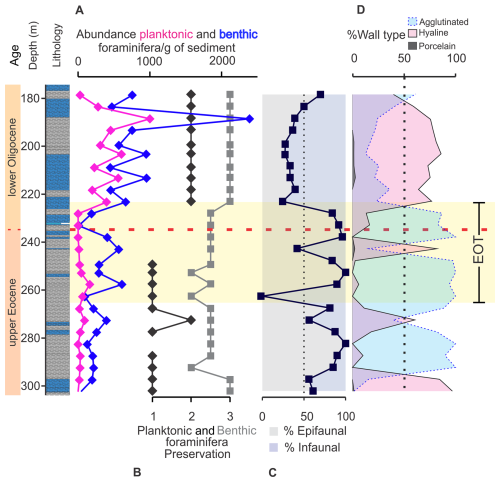

Planktonic foraminifera exhibit low abundances during the upper Eocene, increasing in the lower Oligocene after 223.2 m, with values exceeding 390 individuals per gram of sediment (Fig. 5A). Benthic foraminifera show variable abundances in the upper Eocene, peaking at 610 individuals per gram of sediment at 257.6 m and stabilizing in the Oligocene with a prominent peak at 188.5 m of more than 2000 benthic foraminifera per gram of sediment (K–W p=0.04; ANOVA p=0.7; Figs. 5A, S2, and S3). Preservation improves over time, with planktonic foraminifera transitioning from poor to moderate preservation in the upper Eocene to consistently moderate preservation in the Oligocene. Benthic foraminiferal preservation shifts from moderate to good in the upper Eocene to consistently good after 223.2 m (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5Temporal and depth evolution of indices measured in planktonic and benthic foraminiferal assemblages in the ANH-SJ-1 drill core. The vertical axis represents time (Ma) along with the core lithology (depth in meters). Panel (A) shows the abundance of planktonic and benthic foraminifera per gram of sediment, while (B) illustrates their preservation index. Panels (C) and (D) show the distribution of benthic foraminifera by microhabitat (epifaunal and infaunal) and their distribution by wall type.

Benthic foraminiferal diversity indices (Chao1 and H′) show variable values during the upper Eocene, with occasional peaks above 30, contrasting with consistently higher values in the Oligocene (K–W p=0.005 for Chao1; p=0.002 for H′; Fig. S11C–D). Dominance peaks during the upper Eocene, driven by changes in agglutinated foraminifera such as Psammosiphonella discreta, with contributions from Nothia excelsa and Neugeborina longiscata (Table S4; Fig. S4). In the Oligocene, calcareous foraminifera (hyaline and porcelaneous forms) become more abundant, with shifts between agglutinated and calcareous assemblages showing statistical differences across pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT periods (ANOVA p=0.003; Figs. S4, 5D).

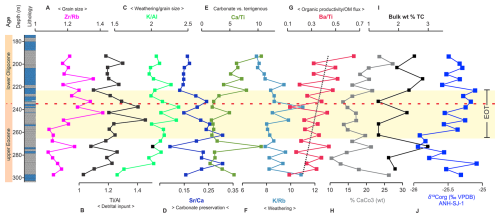

3.5 Geochemical and isotopic proxies

The PCA of XRF-measured elements distinguishes biogenic sources (e.g., Ca, Sr) from terrigenous inputs (e.g., Fe, Ti, K, Al), highlighting a clear separation between marine and continental sources in the analyzed samples (Fig. S5). Terrigenous-related ratios (e.g., ) show consistent patterns, with an increase during the EOT (e.g., : pre-EOT mean = 1.1, EOT mean = 1.2, p=0.0005; Tables S10 and S12) followed by a decrease in the lower Oligocene (post-EOT mean = 1.215). Similarly, increases significantly during the EOT (pre-EOT mean = 0.35, EOT mean = 0.45, p=0.005) before declining in the lower Oligocene (post-EOT mean = 0.17). In contrast, biogenic proxies (e.g., , ) exhibit increased stability and reduced variability after a depth of 228.1 m. , for instance, peaks during the EOT (mean = 0.2, p=0.021) but decreases in the lower Oligocene (mean = 0.154). shows a progressive increase from the upper Eocene to the lower Oligocene, indicating enhanced productivity or biogenic input during this transition (Fig. 6G).

Figure 6Temporal and depth trends of abiotic proxies across the ANH-SJ-1. The vertical axis represents time (Ma) and the core lithology (depth in meters). Panels (A) through (G) show XRF-derived elemental ratios: Zr/Rb (A), Ti/Al (B), K/Al (C), Sr/Ca (D), Ca/Ti (E), K/Rb (F), and Ba/Ti (G). Panel (H) shows the percentage of calcium carbonate (wt % CaCO3), (I) shows the total carbon content (wt % TC), and (J) shows the bulk δ13C organic values (‰ VPDB). The dashed red line indicates the EOB.

Carbonate loss varies between 10 % and 27 %, with higher losses observed after 228.1 m, coinciding with a shift in geochemical ratios. Total carbon (TC) fluctuates without a clear temporal pattern, ranging from 1.31 % to 3.04 %. The δ13Corg values (‰ VPDB) indicate dynamic changes in the carbon cycle, with more negative values (from −25.94 ‰ to −25.08 ‰; Fig. 6I) in the upper Eocene, including a sustained negative excursion at 262.7 m (−25.91 ‰). In the lower Oligocene, δ13Corg variability is reduced, averaging −25.3 ‰ between 228.1 and 193.3 m (Fig. 6J).

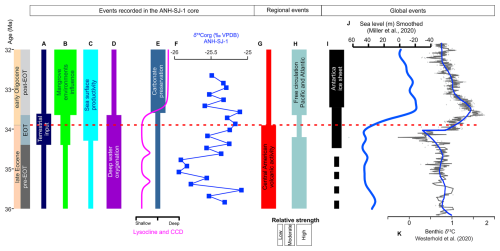

Global climatic changes associated with the EOT, including the growth of the Antarctic ice sheet and a relative drop in sea level (Hutchinson et al., 2021), may have influenced environmental conditions in the Caribbean region (Fig. 7). This study examines how global signals may have interacted with local settings to influence environmental and ecological dynamics in the southwestern Caribbean during this period. The interval under investigation coincides with a phase of relative tectonic stability in the region, attributed to a decreased convergence rate and more oblique motion between the Caribbean and South American plates (Mora-Bohórquez et al., 2017). We assess possible mechanisms behind observed changes in sediment delivery (e.g., sea-level fluctuations, gravity-driven flows) and explore how these processes, together with shifts in marine productivity and carbonate dynamics, may have influenced tropical marine ecosystems. The multiproxy record from the ANH-SJ-1 drill core presents a unique opportunity to assess these interactions during a pivotal climatic transition.

4.1 Was there a sea-level fall in NW South America during the EOT?

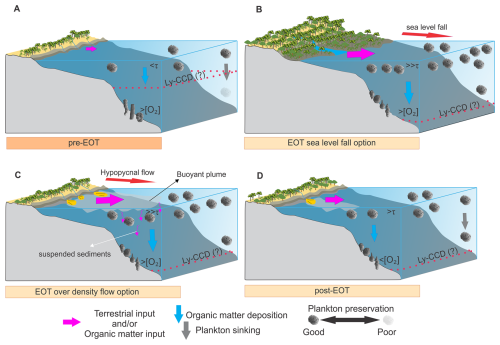

On a global scale, the EOT is widely associated with a significant eustatic sea-level fall, with estimates of up to 50 m reported in regions such as the Gulf of Mexico (Fig. 1; Miller et al., 2008; De Lira Mota et al., 2023). This change, linked to the expansion of Antarctic ice sheets (Miller et al., 2020), likely triggered adjustments in fluvial systems and influenced sediment delivery patterns in various basins. In the ANH-SJ-1 core interval, deposited in a lower bathyal setting (>1000 m; Trejos-Tamayo et al., 2024, 2025a), we observe no major lithological disruptions, but several proxies suggest changes in sediment input during the EOT. Geochemical indicators, including increased , , and ratios, and shifts in palynological assemblages (e.g., increased terrestrial pollen and spores), show elevated values toward the middle of the calculated EOT interval, particularly near the EOB (∼ 238 m; Figs. 3, 6). These trends could reflect intensified terrigenous input during this interval. The index exhibits relatively high values at the onset of the EOT, particularly associated with a high abundance of Polysphaeridium spp. and Spinifirites spp., which dominate the CONISS-defined palynological group P2 (Fig. S2) and are indicative of a stronger marine influence, but it declines toward the EOB, coinciding with an increase in terrestrial palynomorphs (Fig. 3). While suggestive of shifting depositional conditions, these trends should be interpreted cautiously, as transport processes and preservation biases can also influence values.

The ratio exhibits statistically significant changes (p=0.0005), indicating that more erosion-resistant material reaches the basin, potentially under more energetic or variable delivery mechanisms (Boyle, 1983; Dypvik and Harris, 2001; Kylander et al., 2011; Heymann et al., 2013). While does not differ significantly, its overall pattern aligns with a general increase in detrital input. The index, often used to evaluate the relative contribution of marine versus terrestrial input (Peeters et al., 1998; Prauss, 2001; Rull, 2002; Olde et al., 2015), shows a near-significant trend (p=0.06), indicating possible shifts in environmental dynamics. Dinoflagellate richness also declines slightly, although this trend is not statistically significant (K–W p=0.45) and must be interpreted with caution, given the potential for underrepresentation due to oxidation procedures. In this bathyal setting, such a decline could reflect a range of factors, including reduced productivity, taphonomic biases, or changes in nutrient delivery, as interpreted in other environments with similar characteristics (Sluijs et al., 2005; Olde et al., 2015), rather than local ecological collapse.

From ∼ 34.3 Ma (∼ 249.5 m), an increase in mangrove pollen, particularly during the EOT, suggests some reorganization of coastal vegetation or changes in transport pathways. These changes may reflect relative sea-level fluctuations or increased runoff, but the trends are modest (ANOVA p=0.09; K–W p=0.07) and should be viewed as preliminary. Although we do not observe macroscopic sedimentary evidence for regression in ANH-SJ-1, the globally documented sea-level fall supports the possibility of base-level lowering in the region. This could have enhanced erosion on land and sediment delivery to the basin. However, core data from nearby wells (e.g., ANH-SSJ-Nueva Esperanza-1x drill core, ∼ 145 km southwest; Celis et al., 2023; Fig. 1) do not show clear signs of regression, suggesting spatial variability in depositional responses. As an alternative or complementary mechanism, we consider the possibility of hypopycnal flows, sediment-laden freshwater plumes driven by river discharge under stratified conditions (Zavala, 2020). These flows could account for the fine-grained nature of the sediments and enhanced terrigenous signal without requiring direct evidence of regression. Both mechanisms, eustatic sea-level changes and freshwater-driven flows, may have acted in tandem or alternately to shape sedimentation during the EOT.

Tectonic uplift in northern Colombia (Restrepo-Moreno et al., 2009) may have further influenced detrital input, particularly through enhanced river erosion, such as the river systems originating in the Amagá Basin or nearby areas (Pardo-Trujillo et al., 2023; Osorio-Granada et al., 2020; Fig. 1). Fluvial transport likely carried pollen and spores, including mangrove elements (Fig. S12), from coastal and lowland environments into the basin. While these observations support increased terrestrial input, the data do not allow us to distinguish clearly between tectonic, climatic, or eustatic drivers.

In summary, although sedimentological evidence is limited, the integration of multiple proxies suggests enhanced terrigenous influence at ANH-SJ-1 during the EOT. This input may reflect a combination of global sea-level changes, freshwater runoff, and tectonic processes (Fig. 7). Further high-resolution studies would help refine the relative importance of these factors.

Figure 7Summary diagram illustrating the temporal evolution of key events during the late Eocene–early Oligocene interval (∼ 36–32 Ma) as recorded in the ANH-SJ-1 core, along with regional and global events. (A) Based on pollen and geochemical proxies (e.g., ), the terrestrial input indicates an increased continental influence during the EOT. (B) Mangrove environments reached their peak during the EOT and declined afterward, reflecting the dynamic nature of coastal processes. (C) Sea surface productivity, inferred from calcareous nannofossils and ratios, increased significantly during the EOT, driven by nutrient influx. (D) Deep-water oxygenation, as reflected in benthic foraminiferal assemblages, shows declining oxygen levels across the EOT. (E) Lysocline and carbonate compensation depth (CCD) deepened during the EOT, promoting improved carbonate preservation, and the carbonate preservation increased post-EOT, as seen in the higher ratios and greater abundance of calcareous benthic foraminifera. (F) δ13C from the ANH-SJ-1 core. (G) Regional events include volcanic activity in central America, which may have influenced ocean acidification and sedimentary dynamics. (H) Pacific–Atlantic circulation pathways evolved due to the progressive restriction of the CAS. (I) The Antarctic ice sheet expanded during the EOT, driven by global cooling and reductions in atmospheric CO2. (J) Global sea-level fluctuations (Miller et al., 2020) show a significant eustatic fall during the EOT. (K) Global composite δ13C (Westerhold et al., 2020).

4.2 Sea surface productivity

From ∼ 249.5 m onward, several proxies suggest possible increases in surface productivity during the lower Oligocene in NW South America. The Iτ index, used here as a proxy for trophic conditions, shows statistically significant differences between the upper Eocene and lower Oligocene (t test, p=0.02; ANOVA, p=0.03), coinciding with a higher relative abundance of eutrophic and mesotrophic taxa such as C. floridanus, Helicosphaera intermedia, and Reticulofenestra locker (Fig. S3). These taxa have previously been linked to nutrient-rich conditions in coastal upwelling systems, river plumes, or nutrient-enriched waters (Perch-Nielsen, 1985; Cachão and Moita, 2000; Ziveri et al., 2004; Auer et al., 2014), and their increased abundance may point to changes in nutrient dynamics at the site (Fig. 8). The Iτ index trends vary across the three segments (pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT). Pre-EOT values are generally low, suggesting mesotrophic conditions. During the EOT, a rise in eutrophic indicators coincides with increased terrigenous input, which may reflect enhanced nutrient delivery associated with sea-level regression and/or increased erosion. In the post-EOT interval, the Iτ index remains relatively elevated, potentially indicating sustained eutrophic conditions; however, the resolution and sampling frequency limit the detection of short-term variability.

Figure 8Schematic diagram illustrating environmental and depositional changes during the EOT in the Caribbean region of NW South America. (A) Pre-EOT conditions are characterized by a relatively shallow lysocline and carbonate compensation depth (Ly-CCD), with low marine productivity (<τ), high bottom-water oxygenation (> [O2]), and limited terrestrial input. Agglutinated benthic foraminifera dominated, while planktonic microfossil preservation was poor. (B) Sea-level fall option during the EOT, showing an intensified terrestrial and organic matter input and organic matter deposition, contributing to enhanced marine productivity (≫τ). This scenario also involves high bottom-water oxygenation (> [O2]), potential deepening of the Ly-CCD, and increased terrestrial vegetation encroachment. (C) Over-density flow option during the EOT, highlighting hypopycnal flows as a mechanism for increased terrestrial sedimentation. Fine suspended sediments, such as silt and clay, are transported in buoyant plumes, gradually depositing material. (D) Post-EOT conditions, with the establishment of stable coastal environments dominated by mangroves and deepened Ly-CCD. This interval also experienced sustained enhanced marine productivity (>τ) and reduced bottom-water oxygenation (< [O2]). The thickness of the arrows represents relative intensity or magnitude.

Comparable patterns in the Tanzanian Drilling Project (TDP) records from Sites 12 and 17 have linked nutrient enrichment during the EOT to continental-scale glaciation and platform exposure, which may have released organic matter and nutrients into marine systems (Dunkley Jones et al., 2008; Fig. 1). A similar mechanism is plausible for NW South America, where a potential regional regression, combined with fluvial input or sediment reworking, could have contributed nutrients to surface waters. Additionally, sediment gravity flows may have transported fine-grained, nutrient-rich material to deeper environments, although direct evidence for this remains limited. Modern analogs also demonstrate that opportunistic nannoplankton taxa can proliferate in nutrient-enriched environments, particularly in response to riverine inputs and seasonal upwelling (Cachão and Moita, 2000; Cavaleiro et al., 2020; Guerreiro et al., 2023). These analogs provide helpful context for interpreting similar signals in our EOT record, though we acknowledge that multiple variables influence species responses. Elemental ratios such as , , and (ANOVA, p<0.05) further support changes in sediment composition during the EOT. The significant increase in (p=0.0005) may reflect higher detrital input, while (p=0.01) may be linked to changes in carbonate and biogenic components. While not direct proxies for productivity, these geochemical indicators help frame the broader environmental context and support the idea of enhanced material flux to the basin.

The IT° index and the relative abundance of temperate taxa (e.g., C. floridanus and Reticulofenestra spp.) may indicate a shift in surface water conditions. However, the lack of a significant increase in cold-water taxa (ANOVA, p=0.4) suggests that the observed assemblage changes were likely driven more by nutrient availability than by temperature alone. Although regional SST declines of ∼ 6 °C have been documented in nearby areas, such as the Gulf of Mexico (Wade et al., 2012), the absence of temperature-sensitive proxies in our record precludes firm conclusions. Additional paleotemperature reconstructions are needed to clarify the role of cooling at ANH-SJ-1. Current evidence only supports nutrient-driven changes as the dominant factor. The EOB has been linked to reorganizations of global climate and ocean circulation, including enhanced thermal gradients between high and low latitudes (Moore et al., 2014). While our data cannot directly resolve such gradients, the occurrence of C. floridanus, a taxon associated with eutrophic open marine conditions (Auer et al., 2014), together with geochemical signals, may reflect local increases in productivity during the early Oligocene.

The role of ocean circulation in nutrient delivery to the southwestern Caribbean during the EOT remains poorly constrained. During the Paleogene, the Pacific and Atlantic were likely connected via the CAS (Iturralde-Vinent, 2006), although intermittent barriers such as the GAARlandia land bridge may have restricted water exchange (Iturralde-Vinent and MacPhee, 1999). Although our data do not allow direct inferences about circulation patterns, this paleogeographic framework may help contextualize possible nutrient sources. One alternative hypothesis involves proto-Humboldt systems, potential precursors to the modern Humboldt Current, which enhance productivity along the Pacific margin of South America through localized upwelling during the EOT (e.g., the Pisco Basin, Peru; Malinverno et al., 2021; Fig. 1). While their influence on the Caribbean side remains uncertain, this mechanism cannot be ruled out and warrants further investigation.

4.3 Bottom-water productivity

Several micropaleontological and geochemical signals in the ANH-SJ-1 core suggest that export productivity and benthic conditions evolved during the EOT and lower Oligocene. An increase in the relative abundance of infaunal benthic foraminifera (ANOVA, p=0.002; t test, pre-EOT vs. post-EOT, p=0.001) coincides with changes in oxygenation proxies, including estimated bottom-water [O2] and EBFOI values (ANOVA, p=0.02 and p=0.05, respectively). While the number of foraminiferal specimens per gram of sediment was often limited, the observed trends may reflect the development of low-oxygen microhabitats associated with increased organic matter input, as previously documented in similar settings (Jorissen et al., 1995; Jorissen, 1999; Loubere and Fariduddin, 1999; Schmiedl et al., 2003). The apparent increase in infaunal forms could indicate a greater availability of food sources within the sediment, particularly under conditions of enhanced organic matter accumulation. This interpretation is supported by a rise in benthic foraminiferal diversity, reflected in higher values of Shannon (H′) and Chao-1 indices (ANOVA, p=0.004 and p=0.01, respectively). While these increases suggest community restructuring under changing environmental conditions, the data should be viewed cautiously due to the generally low absolute abundances of foraminifera in some intervals.

The ratio also increases near the EOT (ANOVA, p=0.05; Fig. S13), which may reflect higher export productivity and organic matter flux to the seafloor. Barite (BaSO4) formation is linked to the remineralization of sinking organic matter, making Ba a useful, though indirect, proxy for productivity in some settings (Carter et al., 2020). In this case, the pattern complements micropaleontological indicators, suggesting that the benthic response may have been coupled to surface productivity dynamics.

Increased Iτ values in nannofossils (ANOVA, p=0.03) also point to possible nutrient enrichment in surface waters, potentially enhancing export fluxes. Together, these findings are consistent with mechanisms described in other global EOT records, where cooling, sea-level regression, and changes in ocean circulation may have redistributed nutrients and altered productivity (Armstrong McKay et al., 2016; Hutchinson et al., 2021). Additional geochemical indicators, such as lower δ13Corg values, slightly elevated ratios, and higher total carbon (TC), may reflect enhanced preservation or accumulation of organic matter under dysoxic or suboxic conditions. The shift to lighter δ13Corg values is in line with a greater contribution of isotopically light marine organic matter and/or less extensive remineralization during burial (Fig. S13). However, we note that these signals may also be influenced by terrigenous organic matter input, which could affect the interpretation of carbon isotope data.

Although the proxy signals vary in strength and resolution, their combined trends suggest that bottom-water conditions and benthic habitats may have been affected by the increased export of organic material during the EOT. These patterns likely reflect the interaction of regional sedimentary processes and global climatic forcing. Still, given the limitations in sample resolution, foraminiferal recovery, and proxy specificity, we interpret these signals as suggestive rather than conclusive. Future studies with higher-resolution records and more targeted geochemical analyses would help refine these interpretations.

Epifaunal forms dominate in the upper Eocene, except for short periods at 262.7 and 243 m when infaunal forms predominate. In the Oligocene, infaunal forms dominate consistently after 223.2 m (Fig. S11C). This transition toward infaunal dominance in the Oligocene is consistent with declining bottom-water oxygenation, as many infaunal taxa are more tolerant of low-oxygen conditions and can exploit organic-rich microenvironments within the sediment (Jorissen et al., 1995; Jorissen, 1999). Alternatively, or additionally, the increase in infaunal taxa may reflect enhanced phytodetritus export to the seafloor during the early Oligocene, associated with increased surface productivity and reduced microbial degradation under cooler conditions, as suggested by Thomas (1992). Oxygen ([O2]) estimates and EBFOI values indicate highly to moderately oxygenated conditions during the upper Eocene, transitioning to low-oxygen conditions in the Oligocene after 223.2 m (K–W p=0.02; ANOVA p=0.02; Fig. S11D). Notably, three key levels in the pre-EOT, EOT, and post-EOT intervals yielded >100 specimens (Table S4), falling within the recommended range for more robust EBFOI estimations. These points follow the same oxygenation trends observed throughout the record, lending additional confidence to the overall paleoenvironmental interpretation despite lower abundances in other intervals.

When compared to global records, particularly from mid- to high-latitude sites, which document a shift toward more oligotrophic and seasonally pulsed deep-sea ecosystems across the EOT (Alegret et al., 2021), the ANH-SJ-1 record suggests a contrasting pattern. The consistent increase in infaunal benthic foraminifera, along with higher productivity proxies and enhanced terrigenous input, indicates that local nutrient dynamics and organic matter fluxes played a more prominent role in shaping benthic conditions in the tropical Caribbean. By documenting these tropical patterns, our study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the spatial heterogeneity underlying global EOT-related environmental change.

4.4 Controls on carbonate preservation across the EOT

The ANH-SJ-1 core provides evidence of changes in carbonate preservation across the EOT, as indicated by shifts in benthic foraminiferal assemblages and geochemical indicators. In the upper Eocene (∼ 252.9 to ∼ 228.1 m), assemblages are predominantly composed of dissolution-resistant agglutinated taxa such as Ammosphaeroidina pseudoauciloculata, Haplophragmoides stomatus, and Psammosiphonella cylindrica (Fig. S4), suggesting reduced carbonate preservation. In contrast, calcareous forms, including Bulimina macilenta, Cibicidoides mundulus, and Uvigerina auberiana, become more abundant in the lower Oligocene (post-228.1 m; CONISS groups F3 and F4), coinciding with improved carbonate conditions (Figs. 5 and S4). On the other hand, geochemical proxies provide additional support. Lower ratios and wt % CaCO3 values in the upper Eocene (p=0.01) suggest carbonate undersaturation, which may reflect a shallower lysocline and/or CCD under warmer, higher-pCO2 conditions (Rea and Lyle, 2005; Pälike et al., 2012). The δ13Corg values during this time are more negative, potentially consistent with the global presence of isotopically light carbon, possibly originating from the remineralization of organic matter or volcanic emissions. These unfavorable conditions suppressed the preservation of calcareous taxa and favored agglutinated foraminifera, which are more resistant to dissolution (Ortiz and Kaminski, 2012; Kaminski and Ortiz, 2014).

Several regional factors could have contributed to limited carbonate preservation in this setting. Volcanic activity from the central American arc during the late Eocene, recorded at ODP Site 999 (Sigurdsson et al., 1997; Fig. 1), may have contributed to reduced carbonate preservation in the region. Although direct evidence of acidification at this site is lacking, such volcanic episodes could have increased pCO2 levels and delivered volcanic ash to the water column, potentially lowering carbonate saturation. Similar mechanisms have been documented in modern analogs, where volcanic eruptions triggered short-term ocean acidification and impacted carbonate systems (e.g., Santana-Casiano et al., 2013). The presence of agglutinated taxa and low foraminiferal abundance and diversity may also reflect mid-depth oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) conditions, where carbonate dissolution can be intensified (Gooday, 2003; Ortiz and Kaminski, 2012).

Globally, the late Eocene CCD shoaling has been linked to increased atmospheric pCO2 levels (Pälike et al., 2012). A ∼ 0.7 ‰ negative carbon isotope excursion (nCIE) at Site 1218 in the Pacific has been interpreted as the result of light carbon input during early cooling (Taylor et al., 2023a, b; Fig. 1), and model–data comparisons from the Gulf Coastal Plain suggest that sea-level fall may have released stored terrestrial organic carbon (De Lira Mota et al., 2023). These processes may have contributed to transient carbonate undersaturation in the deep ocean. In the lower Oligocene, higher ratios (p=0.01), an increased abundance of calcareous foraminifera, and overall improvements in carbonate preservation suggest a deepening of the CCD and lysocline, consistent with global cooling and declining atmospheric pCO2 (Rea and Lyle, 2005; Pälike et al., 2012). Increased detrital input from continental weathering, as inferred from elevated , , and ratios, may have supplied alkalinity and bicarbonates to marine environments, thereby contributing to the buffering of CO2-driven acidification (Nesbitt et al., 1980). Higher values (p=0.03) point to the weathering of potassium-bearing silicates, which release bicarbonate ions and consume atmospheric pCO2 (Gaillardet et al., 1999; Bosq et al., 2020). The lower ratios (p=0.021) observed may indicate reduced aragonite contribution or increased dominance of low-Sr producers such as coccolithophores (Stoll and Schrag, 2000). These patterns, together with rising diversity indices (H′ and Chao-1), suggest that carbonate preservation improved as calcareous taxa became more prominent in deep-water assemblages.

Overall, the transition into the lower Oligocene at ANH-SJ-1 appears to reflect the combined influence of global climate cooling, reduced atmospheric pCO2, enhanced weathering, and increased terrestrial input. While some of these interpretations are constrained by sample resolution and the complexity of proxy signals, the observed patterns are broadly consistent with trends reported from other basins. Together, they point to a scenario in which both global ocean chemistry and regional sediment dynamics played a role in modulating carbonate preservation during and after the EOT.

This study examines a marine sedimentary record spanning the upper Eocene to lower Oligocene in the southwestern Caribbean of South America, integrating marine and terrestrial microfossils with geochemical proxies. By combining multiple lines of evidence, we explore how tropical ecosystems may have responded to environmental changes during the EOT, a time of global climatic reorganization.

The data suggest that the global sea-level fall during the EOT may have enhanced continental sediment input in the study area, possibly through increased fluvial discharge and sediment transport processes. Geochemical ratios (e.g., , , ) and shifts in palynological assemblages, including an increase in mangrove pollen, indicate a stronger terrestrial influence, even in deep bathyal settings. While no macroscopic sedimentological evidence of regression is observed, sediment delivery via density flows may have contributed, suggesting a more complex interaction between regional and global processes.

Beginning around 34.3 Ma, enhanced surface productivity is inferred from increased calcareous nannofossil abundances and higher trophic index (Iτ) values. The dominance of eutrophic taxa, such as C. floridanus and Reticulofenestra spp., suggests that nutrient enrichment, likely linked to terrigenous inputs, played an important role in reshaping planktonic communities. However, other factors, such as surface water temperature or stratification, cannot be entirely ruled out.

A shift from agglutinated to calcareous benthic foraminiferal assemblages is observed across the transition, which may indicate improved carbonate preservation. This is supported by rising ratios, CaCO3 content, and an increase in calcareous taxa. Such changes could reflect the deepening of the lysocline and the carbonate compensation depth (CCD), potentially driven by increased ocean alkalinity resulting from continental weathering and global CO2 drawdown.

The δ13C signal recorded in the ANH-SJ-1 core exhibits excursions that are broadly consistent with global reference curves, including positive shifts at approximately 34.2 and 33.7 Ma. Although resolution constraints limit precise alignment, these trends likely reflect broader changes in the carbon cycle, influenced by regional factors such as freshwater influx and nutrient delivery.

Taken together, the results highlight environmental and ecological reorganization in the southwestern Caribbean during the EOT. Despite limitations such as a relatively low number of samples and modest microfossil abundance, common in studies of exploratory well material, the multiproxy approach yields a coherent picture of change across this interval.