the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Environmental changes at the seafloor of the Faro drift (Gulf of Cadiz) during the transition from the Early to the Middle Pleistocene

Giulia Silveira Molina

Gerhard Schmiedl

Francisco Jiménez-Espejo

Henning Kuhnert

Teresa Rodrigues

Antje Helga Luise Voelker

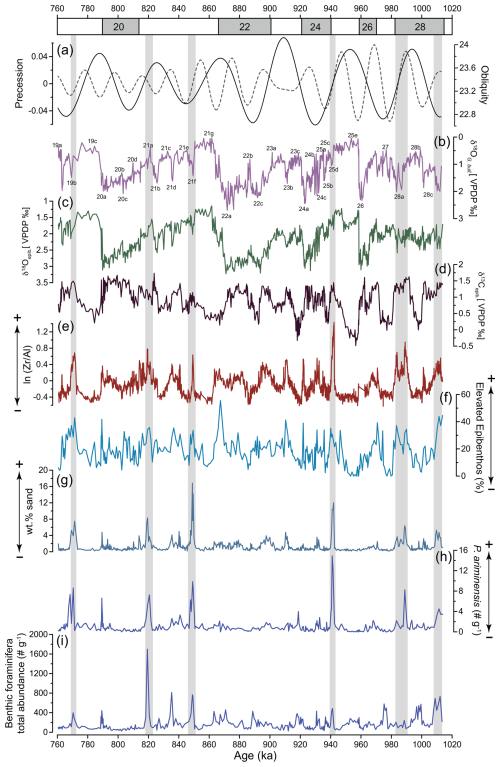

This study explores the ecology of the benthic foraminifera fauna and reconstructs bottom water oxygenation, organic matter fluxes, and Mediterranean Outflow Water (MOW) dynamics in the Gulf of Cadiz during the Early to Middle Pleistocene Transition (EMPT) interval of Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 28 to MIS 19 (1014–761 ka) using high-resolution multiproxy data from IODP Site U1387. Along with benthic foraminifera assemblages, we integrate stable isotopes (δ18O and δ13C), organic carbon, alkenone concentrations, and geochemical and sedimentological proxies ( ratio, grain size) to identify environmental drivers across glacial–interglacial cycles and millennial-scale events. Furthermore, the absolute abundance of Planulina ariminensis is applied as a proxy for bottom current strength. Principal component analysis confirms assemblage responses to variations in organic matter quality and oxygenation. Periods of intensified MOW during stadial climate stages correspond to enhanced bottom water ventilation, reflected in higher abundances of epifaunal and porcelaneous taxa, higher diversity, and increased dissolved oxygen, with the exception of the late MIS 22. Intervals of reduced ventilation (e.g. interglacial MIS 27, MIS 25e, MIS 21g, MIS 19c) coincide with higher total alkenone concentrations, potentially contributing to low oxygen conditions and increased proportions of infaunal taxa. Our results reveal that bottom water dynamics at Site U1387 were controlled by local oceanographic processes (e.g. coastal upwelling, river discharge, water column stratification) rather than by global ice volume changes only. These findings highlight the importance of understanding regional oceanographic variations during the EMPT and emphasize the value of combining food supply, oxygenation, and bottom current proxies to interpret benthic foraminifera ecological changes.

- Article

(9280 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1149 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The Mid-Pleistocene Transition or Mid-Pleistocene Revolution (e.g. Clark et al., 2006; Herbert, 2023; McClymont et al., 2013), after the ratification of the lower boundary of the Pleistocene at 2.58 Ma, stratigraphically correctly referred to as the Early to Middle Pleistocene Transition (EMPT) (Head and Gibbard, 2015), was a global climate event that occurred between 1400 and 424 thousand years (kyr) ago. It may have been initiated by changes in ocean–atmosphere coupling linked to the growth of the Northern Hemisphere ice sheets during glacial periods (Head and Gibbard, 2015; McClymont et al., 2013). Prior to the EMPT, the glacial cycles were dominated by the 41 kyr obliquity cycle and then changed to longer and more intense glaciations, occurring at a spacing of approximately 100 kyr. These cycles were commonly attributed to eccentricity, which also controls the amplitude of precession-driven seasonal insolation (Hays et al., 1976; Imbrie et al., 1992; Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005). The EMPT was marked by a drastic change in the deep thermohaline circulation (Elderfield et al., 2012; Farmer et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021; Raymo et al., 1997) and facilitated the simultaneous decrease in atmospheric CO2 (Farmer et al., 2019; Head and Gibbard, 2015; Hines et al., 2024; McClymont et al., 2013; Nuber et al., 2025; Scherrenberg et al., 2025).

Beyond the long-term orbital-scale changes, millennial-scale climate variability has been observed in North Atlantic climate records during the EMPT (e.g. Billups and Scheinwald, 2014; Hodell et al., 2023; Hodell and Channell, 2016). Although these events were relatively short in duration (lasting between 1 and 10 kyr), they had significant impacts on deep-ocean circulation and the global climate system (e.g. Hodell et al., 2023; Hodell and Channell, 2016; Thomas et al., 2022). Therefore, understanding the regional response to these global changes, particularly in sensitive areas such as the Gulf of Cadiz (e.g. Mega et al., 2025), is essential to reconstruct the mechanisms that drove this climatic transition.

The Mediterranean Outflow Water (MOW) is a key feature of the Gulf of Cadiz, representing a warm and saline intermediate-depth water mass that exits the Mediterranean Sea through the Strait of Gibraltar and flows along the southeast Iberian margin (Baringer and Price, 1997; Rogerson et al., 2012). This outflow contributes to the regional hydrography and global thermohaline circulation by injecting warm high-salinity water into the North Atlantic Ocean (Baringer and Price, 1997; Reid, 1979; Rogerson et al., 2012). Past fluctuations in MOW intensity and pathways have been associated with regional hydrographic changes during glacial–interglacial periods, impacting on seafloor conditions in the Gulf of Cadiz. Palaeoceanographic studies suggest that stronger MOW flow during cooler climate periods enhanced bottom current strength and ventilation of mid-depth waters in this region (Schönfeld, 1997; Singh et al., 2015; Voelker et al., 2015). Such variations in MOW have left imprints on sedimentary deposits and benthic faunal assemblages (García-Gallardo et al., 2017a; Lebreiro et al., 2018; Schönfeld and Zahn, 2000). However, the behaviour of MOW and its ecological impact during the EMPT remain poorly understood due to the lack of high-resolution benthic records from this interval.

Benthic foraminifera are widely used as a proxy to reconstruct past environmental conditions at the seafloor. They inhabit specific epifaunal and infaunal microhabitats (Corliss, 1985), reflecting adaptations to the food availability and biogeochemistry in the upper few centimetres of the sediment (Fontanier et al., 2002; Jorissen et al., 1995). Accordingly, the diversity and species composition of the benthic foraminiferal fauna can provide insights into bottom water oxygenation (Kaiho, 1999; Kranner et al., 2022), food supply (Altenbach, 1992; Grunert et al., 2015; Poli et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2022), and bottom current velocity (Saupe et al., 2023; Schönfeld, 1997, 2002a, b; Schönfeld and Zahn, 2000). Species-specific ecological preferences allow for the interpretation of oxygen levels (oxic vs. dysoxic), organic matter fluxes (labile vs. refractory), and hydrodynamic energy. This ecological sensitivity was especially important during the EMPT, when shifts in ocean circulation and productivity led to major impacts on benthic community stability.

During the EMPT, the benthic foraminifera showed a significant ecological turnover, which resulted in a global extinction of deep-sea species around 800 to 600 ka (Hayward et al., 2012; Hayward and Kawagata, 2005; Kawagata et al., 2005; Kender et al., 2016). Kender et al. (2016) showed that the EMPT benthic foraminifera extinction of the Stilostomella group was likely driven by changes in the food quality and a more seasonal food supply, linked to phytoplankton evolution, rather than bottom water hydrography itself. High-resolution records from the East Equatorial Pacific demonstrate that benthic foraminifera communities were highly sensitive to shifts in food supply and bottom water oxygenation during this period (Diz et al., 2020). These studies demonstrated that benthic foraminifera responded to the complex interactions between surface ocean productivity, carbon export, and bottom water oxygenation across the EMPT.

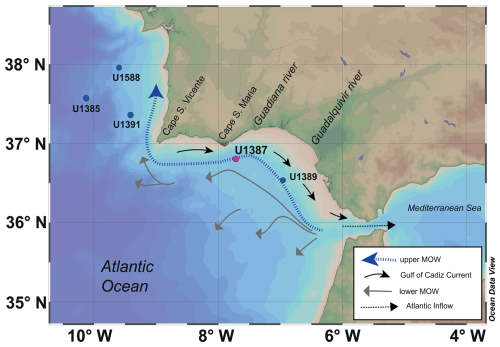

2.1 General circulation

The Gulf of Cadiz is located on the southwestern margin of the Iberian Peninsula in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 1). It is situated west of the Strait of Gibraltar, which connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean. At intermediate depths, the MOW is the dominant water mass in the Gulf of Cadiz (Carracedo et al., 2016), and it is more saline and warmer (> 36 practical salinity unit, PSU; temperature of approximately 13 °C) than the surrounding water masses (Ambar and Howe, 1979a; Carracedo et al., 2016; Louarn and Morin, 2011; Price et al., 1993). At present, most of the MOW encompasses warm, saline waters originating from the eastern Mediterranean Sea, including the Levantine Intermediate Water (LIW) and Western Mediterranean Deep Water (WMDW) (Millot et al., 2006; Rogerson et al., 2012). LIW forms in the Levantine Sea and plays a crucial role in preconditioning deep-water convection in the Adriatic and the Aegean seas, where the Eastern Mediterranean Deep Water (EMDW) is formed (Candela, 2001). Together, EMDW and LIW exit the eastern Mediterranean via the Strait of Sicily as Eastern Mediterranean Source Water (EMSW), which contributes to the formation of WMDW in the Gulf of Lions (Millot, 1987). WMDW and EMSW exit the Mediterranean Sea and flow into the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar, producing what is known as MOW (Millot, 1987). Once MOW flows through the Strait of Gibraltar, it sinks due to its higher salinity, flows down the continental slope, and creates two main core layers: the upper MOW layer at 500–800 m depth and the lower MOW layer at 800–1400 m depth (Ambar and Howe, 1979a, b; Baringer and Price, 1997).

Above the upper MOW, the subsurface Eastern North Atlantic Central Water (ENACW) is formed by subduction during winter, between 100 and 600 m. In addition, a low-salinity, oxygen-poor, and nutrient-rich intermediate water that corresponds to remnants of the Antarctic Intermediate Water has been identified in the Gulf of Cadiz (Cabeçadas et al., 2002; Carracedo et al., 2016; Louarn, 2008; Louarn and Morin, 2011). Its presence is observed overlying the lower MOW, between 700 and 1000 m water depth, but it is absent in the depth range of the upper MOW (Cabeçadas et al., 2002). To the west and offshore, beneath the lower MOW and at depths between 1600 and 2000 m, the basin is occupied by North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) (Cabeçadas et al., 2002).

Figure 1Map of the Gulf of Cadiz showing the indication of IODP Site U1387 (in magenta), along with the other discussed sites: Site U1588, Site U1391, Site U1385, and Site U1389 (in blue). Arrows indicate the general pathways of the upper and lower Mediterranean Outflow Water (MOW), the Gulf of Cadiz Current, and the Atlantic inflow into the Mediterranean Sea, based on Hernández-Molina et al. (2016) and Peliz et al. (2009). The dashed blue arrow represents the upper MOW, the grey arrows represent the lower MOW, the black arrows represent the Gulf of Cadiz Current, and the dashed black arrow represents the Atlantic. This map was generated using Ocean Data View (ODV) (Schlitzer, 2025).

2.2 The MOW in the Gulf of Cadiz

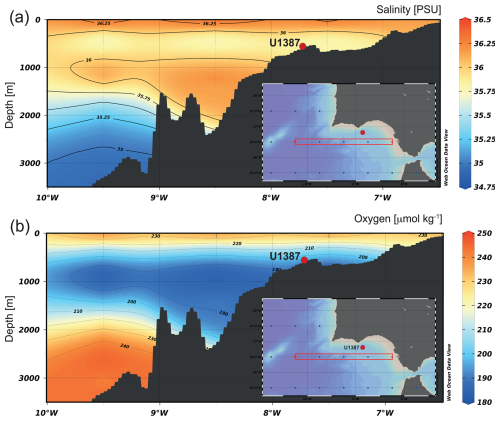

The water masses contributing to the MOW are relatively young, yet their oxygen content is lower compared to the ENACW ([O2] 180 to 190 µmol kg−1) and the underlying NADW ([O2] 190 to 210 µmol kg−1) (Fig. 2) (Ambar et al., 2002; Cabeçadas et al., 2002; Carracedo et al., 2016). Besides that, dissolved oxygen and nutrient concentrations differ between the two cores of the MOW. While the upper MOW is more oxygenated but nutrient-poor ([O2] 170 to 200 µmol kg−1; [NO3] 9 to 11 µmol kg−1; [PO4] 0.5 to 0.7 µmol kg−1), the lower MOW is less oxygenated and more nutrient-rich ([O2] 170 to 180 µmol kg−1; [NO3] 11 to 14 µmol kg−1; [PO4] 0.7 to 1.2 µmol kg−1) (Ambar et al., 2002; Cabeçadas et al., 2002; Carracedo et al., 2016).

Figure 2Vertical sections of (a) salinity (PSU) and (b) dissolved oxygen (µmol kg−1) in the Gulf of Cadiz, with the location of the IODP Site U1387 marked by a red dot. Figures were made with Ocean Data View (ODV) software (Schlitzer, 2025) using the data package of Reagan et al. (2024). Temperature data are not shown but exhibit a similar distribution pattern to salinity.

As it exits the Strait of Gibraltar, the MOW flows mostly northward and northwestward along the (south)western Iberian margin. As a result of its high density, the MOW forms a strong bottom current, with an average velocity of approximately 0.5 m s−1, a temperature of 13.7 °C, and a salinity of 37.1 (Ambar and Howe, 1979b; García et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 1999; Zenk, 1975). This flow is significantly influenced by the Coriolis force, which causes the water to descend the continental slope in a clockwise direction (Gasser et al., 2017; Price et al., 1993). The bottom current of the MOW favours the formation of contourite drift deposits (Contourite Depositional System) in the Gulf of Cadiz, providing the basis for palaeoceanographic studies (Expedition 339 Scientists, 2013; Hernández-Molina et al., 2016).

2.3 Productivity regime

The Gulf of Cadiz experiences seasonal upwelling driven by northerly winds in spring and summer, enhancing offshore Ekman transport and bringing cold and nutrient-rich waters to the surface (Sánchez and Relvas, 2003). In the absence of these favourable winds, a warmer coastal counter current from the Gulf of Cadiz transports nutrient-poor waters to the west, reducing the biological productivity (Cravo et al., 2013; Fiúza, 1983; Navarro and Ruiz, 2006). Among the upwelling regions off southern Portugal, Cape São Vicente and Cape Santa Maria both influence the study area, but they differ in their dynamics and contributions. Whereas Cape São Vicente is a major upwelling centre where strong coastal winds and abrupt changes in coastline orientation intensify upwelling, Cape Santa Maria upwelling is less pronounced and more sporadic (Sánchez and Relvas, 2003). Additionally, the Gulf of Cadiz receives significant river discharge, particularly from the Guadalquivir and Guadiana rivers. These rivers supply freshwater, clays, and nutrients to the basin, promoting primary production (Abrantes, 1990; Alonso et al., 2016; Prieto et al., 2009). Large rivers promote productivity significantly on the continental shelves, especially during periods of high fluvial discharge. Drivers may include intensification of the North African Monsoon and/or increased winter precipitation in the Mediterranean region and its adjacent areas related to the North Atlantic Oscillation (Bosmans et al., 2015, 2020; Toucanne et al., 2015).

3.1 Sample material, grain size analysis, and chronology

This study is based on Site U1387 (36.8° N, 7.7° W) retrieved during IODP Expedition 339 (Mediterranean Outflow) by the JOIDES Resolution and drilled on the middle slope of the Faro drift at a modern water depth of 559 m (Stow et al., 2013). Samples were obtained at an interval of every 12–13 cm along the revised spliced sequence (Voelker et al., 2018) at a depth range of 231.05 to 182.13 m below the seafloor (m b.s.f.), corresponding to 269.33 to 198.84 c-mcd (c-mcd denotes corrected metres composite depth). Sample preparation for foraminiferal and grain size analysis followed the established procedures of the Sedimentology and Micropaleontology Laboratory of the Division for Geology and Marine Georesources at the Portuguese Institute for the Sea and Atmosphere (IPMA) (Voelker et al., 2015), where the samples are permanently archived. The samples were weighted both before and after freeze-drying to determine their wet and dry weights, respectively. After freeze-drying, each sample was washed with water through a 63 µm mesh sieve. The coarse-fraction residue was then dried at 40 °C on filter paper and weighted. The sand content (wt %) was calculated by measuring the weight of the fraction > 63 µm and expressing it as a percentage of the total dry sediment weight ([weight > 63 µmtotal dry weight of sediment] ×100).

The chronostratigraphy was established based on the stable oxygen isotope record of Globigerinoides bulloides and by tuning the Site U1387 record to the one of Site U1385 (Mega et al., 2025; Voelker et al., 2025a, b). For Site U1387, the G. bulloides specimens were collected from the > 250 µm fraction and the stable isotope analyses conducted at MARUM, University of Bremen, using Finnigan MAT-251 and MAT-252 mass spectrometers coupled to a Kiel I or Kiel III automated carbonate preparation system, respectively, with a reproducibility of ±0.07 ‰ for δ18O for the internal standard (Solnhofen limestone). The latter was calibrated against NBS-19. Although part of the record was previously published based on a speleothem-related age model (Bajo et al., 2020), here, we apply the same age models (Voelker et al., 2025b) as those used in Mega et al. (2025). This model is based on a correlation with the LR04 stack (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005) and another with the Probstack of Ahn et al. (2017) (Fig. S1). This allows for a direct comparison between the results of both studies. Accordingly, the studied depth range corresponds to Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 28 to MIS 19, covering from 1013.73 to 760.70 ka. We adopt MIS boundaries from Lisiecki and Raymo (2005) and follow the substage nomenclature proposed by Railsback et al. (2015) for the last 1050 kyr. Identification of interglacial intervals is in conformity with the Past Interglacials Working Group of PAGES (2016) and the sea-level high stand indication (Rohling et al., 2014, 2021). Colder climate periods of the millennial-scale oscillations are referred to as stadials, and warm (temperate) climate periods are referred to as interstadials following the climatostratigraphic concept (Gibbard, 2018).

The sedimentation rate varies significantly across the studied interval (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). The highest sedimentation rate is observed during MIS 24, with values reaching 68.92 cm kyr−1, while other high values are present in MIS 22 (51.13 cm kyr−1) and MIS 19a (59.94 cm kyr−1). In contrast, the lowest sedimentation rates occur during MIS 19c (9.01 cm kyr−1) and MIS 21g (11.79 cm kyr−1). For the benthic foraminifera assemblage analyses, the sample spacing was, in general, between 24–25 cm, corresponding to an average temporal resolution of approximately 1 kyr. However, during intervals of reduced sediment deposition, the sampling spacing was decreased to 12–13 cm to keep the temporal resolution high.

3.2 Benthic foraminifera stable isotope analyses (δ13C and δ18O)

The epibenthic δ13C and δ18O data, published here for the first time, have, in general, a spacing of 12 to 13 cm, which was decreased to 6 cm during the MIS 22-MIS 21 transition. Two benthic foraminifera species, Cibicides pachyderma and Planulina ariminensis, were selected for the analyses as neither species was present continuously. For each species, two to eight specimens were picked from the > 250 µm fraction and subsequently analysed. For the studied interval, several benthic foraminifera isotope samples in the spliced interval between cores U1387B-20X and U1387A-26X were measured in the stable isotope laboratory of the GeoZentrum Nordbayern at the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg (Germany) in early 2014. There, the carbonate powders were reacted with 103 % phosphoric acid at 70 °C using a Gasbench II connected to a ThermoFinnigan Five Plus mass spectrometer. The values are reported in per mil relative to the VPDB standard by assigning δ13C and δ18O values of +1.95 ‰ and −2.20 ‰ to NBS19, −46.6 ‰ and −26.7 ‰ to LSVEC, and 0.13 ‰ and −5.78 ‰ to Sol 2 (internal Solnhofen limestone standard). Reproducibility was monitored by replicate analysis of all three laboratory standards and is better than ±0.05 ‰ for δ13C and better than 0.08 ‰ for δ18O (based on the lower reproducibility for Sol 2). Additional samples, especially from core sections added into the revised splice or where the resolution was increased later (e.g. U1387B-22X-3 to U1387B-22X-6), were measured at MARUM (University of Bremen, Germany) using a Finnigan MAT-251 mass spectrometer coupled to an automated Kiel I carbonate preparation system with a repeatability of ±0.04 ‰ for δ18O and ±0.03 ‰ for δ13C for the internal standard (Solnhofen limestone). No systematic offsets were observed between the benthic foraminifera samples measured at the GeoZentrum Nordbayern and at MARUM. The individual results were combined for the high-resolution and splice-corrected time series presented here. Although parallel measurements between C. pachyderma and P. ariminensis occasionally revealed differences in δ18O, no correction was applied following Marchitto et al. (2014) and Voelker et al. (2015). On the other hand, the δ13C values of C. pachyderma were adjusted by +0.3 ‰ to the P. ariminensis level, following Voelker et al. (2015).

3.3 Micropaleontological analyses

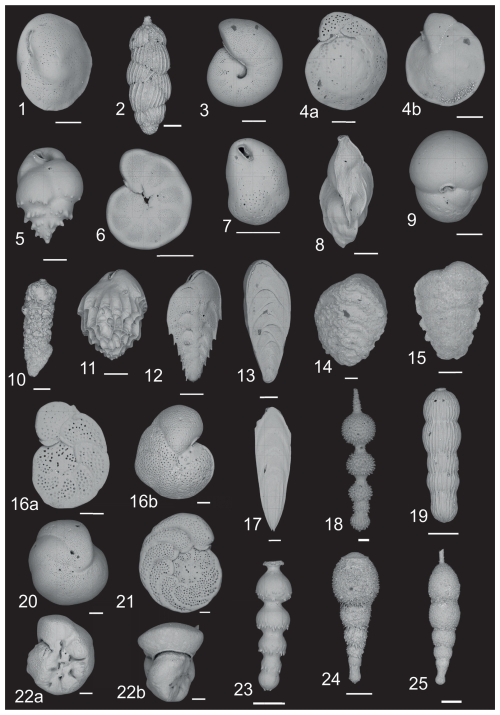

The material for benthic foraminifera identification was first sieved into two size fractions, namely > 250 and 250–125 µm, to ensure comparability with previous studies from the Iberian Margin. A minimum of 300 specimens were counted per sample from the combined fractions. Large samples were split into equal halves to facilitate counting, with the number of splits being carefully recorded to calculate the total number of foraminifera in each sample (Schönfeld, 2012). The number of specimens of C. pachyderma or P. ariminensis that were used for the carbon and oxygen isotopes analysis were added to the totals in the end. Once split, the specimens were identified at the species level and counted. Species assignment mainly followed Caralp (1984), Cita and Zocchi (1978), Jones (1994), Milker and Schmiedl (2012), and Schönfeld (2006). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were used to verify and confirm species identification. The SEM images were obtained with the Tabletop Scanning Electron Microscope Hitachi TM4000PlusII of the EMSO-GOLD laboratory of the Division for Geology and Marine Georesources at the Portuguese Institute for the Sea and Atmosphere (IPMA). The relative abundances of benthic foraminifera were calculated for both fractions separately (> 250 and 250–125 µm) and then summed for the totals. We used this approach to be comparable with other studies. However, the calculation of the group called “elevated epibenthos” only includes the total numbers of the > 250 µm size fraction, with the percentages being relative to the total number of epifaunal benthic foraminifera in the fraction of > 250 µm (Rogerson et al., 2011; Schönfeld, 1997, 2002a, b). This group encompasses Cibicides lobatulus, Cibicides refulgens, Discanomalina coronata, Discanomalina semipunctata, Gavelinopsis translucens, Hanzawaia concentrica, Planulina ariminensis, Textularia sagittula, and Vulvulina pennatula.

Although García-Gallardo et al. (2017a, b) questioned the reliability of using C. lobatulus and C. refulgens as indicators of the elevated epibenthos group, our study found very few specimens of allochthonous species (such as Elphidium spp., Ammonia spp., Asterigerinata spp., Planorbulina mediterranensis, and Rosalina spp.). Therefore, in this study, we include C. lobatulus and C. refulgens within the elevated epibenthos group. Additionally, we also calculated the total number of P. ariminensis specimens > 125 µm per gram of dry sediment as an indicator of strong bottom currents associated with the MOW, as well as total benthic foraminifera abundance > 125 µm g−1. The application of absolute numbers of P. ariminensis ensures that its ecological signal is not masked by variations in the overall community composition or the relative dominance of other taxa.

The abundances of epifaunal, deep-faunal, and infaunal taxa, along with the porcelaneous and agglutinated shell types of benthic foraminifera, have also been analysed and are listed in Appendices A and B. Following the approach of Schönfeld (2001) and Jorissen et al. (2007), Chilostomella spp. and Globobulimina spp. serve as qualitative proxies for significantly depressed oxygenation levels, whereas the porcelaneous and epifaunal taxa indicate well-ventilated environments with low organic carbon content in surficial sediments (Corliss and Chen, 1988; Kaiho, 1999). Additionally, infaunal species are associated with elevated organic carbon flux and potentially low oxygen conditions (Gooday, 2003; Jain et al., 2007).

To estimate dissolved oxygen levels, we used the relative abundances of taxa classified into oxic, suboxic, and dysoxic categories based on their modern microhabitat preferences (Jorissen et al., 1995; Kaiho, 1994; Kranner et al., 2022). Following this classification, the Enhanced Benthic Foraminifera Oxygen Index (EBFOI) was calculated, and the transfer function from Kranner et al. (2022) was applied using the full proportion of oxic species as suggested by Schmiedl et al. (2023) to estimate the dissolved oxygen values (mL L−1). The detailed discussion of changes in oxygen concentrations will be the focus of a future paper. The Shannon diversity index was determined based on the relative abundances in combined size fractions using the PAST software, version 4.15 (Hammer et al., 2001). The Shannon Index and EBFOI are both derived from the same foraminiferal assemblage and, therefore, are not independent datasets, whereby diversity tends to be low at both trophic extremes (oligotrophic and eutrophic conditions) and generally follows a unimodal relationship with oxygen content and food availability (Gooday et al., 2000).

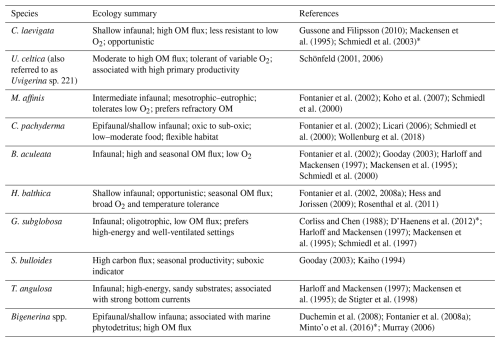

In addition to examining species variation, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to identify patterns and affinities within the extensive group of species. For this purpose, Q- and R-mode (Varimax-rotated) PCAs were applied to the faunal assemblages following Schmiedl and Mackensen (1997) (Table S1 in the Supplement). In this analysis, the different species belonging to the genera Dentalina, Fissurina, Lagena, Lenticulina, Pyrgo, and Quinqueloculina were lumped together as “spp.”, and species with relative abundances below 2 % were omitted. All relative abundances of the species are presented in File S2 in the Supplement, and the ecological interpretation for the 10 most abundant species is summarized in Table 1.

3.4 Organic geochemical analyses

The total organic carbon (TOC) content and alkenone concentration were measured on splits from the same samples that were washed for the benthic foraminifera assemblage analyses. Thus, the sample series are generally spaced at 24 to 25 cm intervals, whereby the lipid biomarker analyses have a higher resolution during the MIS 22–MIS 21 transition (Mega et al., 2025). The TOC content of the sediment was determined following the procedure described in Voelker et al. (2015). Sediment aliquots were analysed using a CHNS-932 LECO elemental analyser after drying and homogenization. To calculate organic carbon content, inorganic carbon was removed by burning a second aliquot at 400 °C, and the difference between total and inorganic carbon concentrations was used. The relative precision of repeated measurements was 0.03 wt %.

The total alkenone concentration, used to reconstruct phytoplankton (coccolithophore) productivity (Villanueva et al., 1998), was obtained for the Site U1387 samples through molecular lipid analysis. The organic compounds were extracted from the freeze-dried, ground samples using sonication with dichloromethane (described in detail in Villanueva et al., 1997). Hydrolysis with 6 % potassium hydroxide in methanol was performed to remove fatty acid and methyl esters, and neutral lipids were extracted with hexane, evaporated under a N2 stream, and derivatized with bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide. Lipids were analysed using a Varian Gas Chromatograph Model 3800 equipped with a septum programmable injector and flame ionization detector in the biogeochemistry laboratory of the EMSO-GOLD facility at IPMA (Rodrigues et al., 2017). The concentrations of haptophyte-synthesized C37 alkenones were determined (in ng g−1) using nonadecan-1-ol, hexatriacontane, and tetracontane as internal standards.

3.5 Major element analysis

Down-core variations in 31 elements were measured in the archive half-sections at 3 cm intervals using the AVAATECH Core Scanner II at the Bremen Core Repository (MARUM, Germany) (Bahr et al., 2014). The sediment sections were covered with a 4 µm SPEXCerti Prep Ultralene1 foil to prevent contamination and dehydration. Data acquisition involved three runs over a 1.2 cm2 area with a 20 s sampling time, employing generator settings of 10, 30, and 50 kV and currents of 0.2, 1.0, and 1.0 mA, respectively. Measurements were captured using a Canberra X-PIPS Silicon Drift Detector (Model SXD 15C-150-500) with 150 eV X-ray resolution and a Canberra Digital Spectrum Analyzer (DAS 1000). The scanner utilized an Oxford Instruments 50 W XTF5011 X-ray tube with rhodium (Rh) as the target material. Raw data spectra were processed using the iterative least-square software package from Canberra Eurisys (Bahr et al., 2014).

Under intensified bottom current activity, the ratio reflects the relative enrichment of heavy minerals such as zircon over less dense minerals. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, ln() was used as this ratio has been suggested as an effective indicator of bottom current strength at the studied location (Bahr et al., 2014; Lebreiro et al., 2018; Voelker et al., 2015).

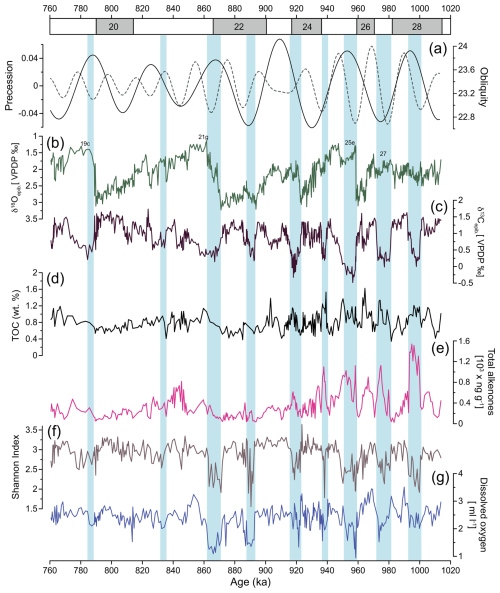

4.1 Epibenthic oxygen and carbon isotope records

The epibenthic δ18O record (Fig. 4) exhibits typical glacial–interglacial variations, showing higher epibenthic δ18O values during low-sea-level-stand glacial periods and lower values during higher-sea-level-stand interglacial and interstadial periods. Values vary between 1.1 ‰ and 3.2 ‰. The epibenthic δ13C record (Fig. 4) displays a pattern generally following the epibenthic δ18O record, with excursions to lower (higher) values occurring synchronously. Values range between −0.4 ‰ and 1.7 ‰. Low epibenthic δ13C values are observed during the interstadial MIS 28b, and pronounced minima occur during interglacial MIS 27 and MIS 25e. A notable excursion also occurred during the MIS 24-MIS 23 transition, although it is of lower magnitude compared to MIS 25e. From MIS 24 to MIS 19, the record reveals occasional periods of low epibenthic δ13C values, but these are not as pronounced as those observed in the earlier part of the studied interval.

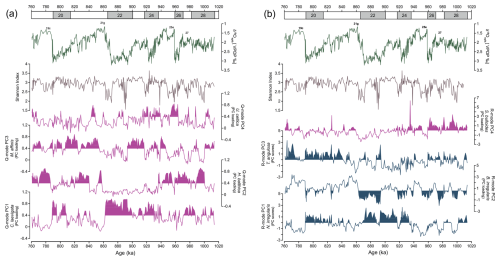

4.2 Benthic foraminiferal records

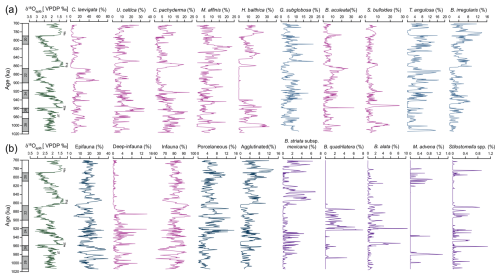

For this study, 323 samples were analysed for benthic foraminifera data, comprising a total of 125 identified species and 92 genera. The 10 most dominant species are illustrated in Appendix C; their relative abundances are presented in Fig. 3a. These species include Cassidulina laevigata, Uvigerina celtica, Melonis affinis, Cibicides pachyderma, Bulimina aculeata, Globocassidulina subglobosa, Sphaeroidina bulloides, Trifarina angulosa, and Bigenerina irregularis.

Species abundance trends across the EMPT reveal distinct temporal patterns associated with MIS and substages. C. laevigata reaches its highest relative abundances during MIS 24 (35.3 %) and MIS 22 (61.6 %) while exhibiting minimum values (near 0 %) in MIS 19, MIS 21, MIS 23, and MIS 25. U. celtica abundance varies markedly throughout the EMPT, with peaks during MIS 25e (34.3 %) and MIS 21f (28.7 %). C. pachyderma displays higher percentages (up to 23.2 %) during MIS 28b, MIS 27, MIS 24, MIS 21g, and MIS 19c, but abundance declines abruptly to near-zero values between MIS 23 and MIS 22. M. affinis exhibits variable abundances, with a notable maximum during MIS 21a (23.6 %) and minimums during MIS 28b and MIS 27. Similarly, H. balthica follows the trend of C. pachyderma, with 32.4 % during MIS 28b, decreasing to 0 % between MIS 24 to MIS 22. G. subglobosa, B. aculeata, and S. bulloides each reveal variable relative abundances, reaching maxima of 21.2 %, 33 %, and 27.4 %, respectively. G. subglobosa abundance has two prominent maxima in MIS 20 (21.5 %) and in MIS 21f (21.6 %) and minima during the interglacial MIS 19c and MIS 21g and the interstadial MIS 21e and MIS 28b. B. aculeata shows its highest abundance in MIS 25e (33 %) and elevated values during MIS 28b (18.6 %), MIS 21g (26.7 %), and MIS 19c (19.6 %). A similar pattern is observed for S. bulloides, with significant peaks during MIS 28b (19.6 %), MIS 25e (27.4 %), MIS 21g (9.9 %), and MIS 19c (8.9 %). In contrast, T. angulosa presents lower percentages during the interglacial MIS 25e, MIS 21g, and MIS 19c and the interstadial MIS 28b, but it increases to its maximum values (up to 17.4 %) during the stadial and glacial MIS 28c, MIS 24, MIS 22, and MIS 20. Finally, B. irregularis reaches its highest abundance (13.8 %) during interglacial MIS 21g and MIS 19c, but it is absent (0 %) in interglacial MIS 25e.

A few allochthonous species (Ammonia spp., Elphidium spp., P. mediterranensis, and Rosalina spp.) were identified within the samples. Due to their low abundance and sporadic occurrence, these species were not included in the infaunal and epifaunal groups. The epifaunal and infaunal taxa (Fig. 3b) show variability throughout the interval, with opposite trends. Higher percentages of the epifauna group and lower percentages of the infauna group are observed during MIS 28a, MIS 26, MIS 24, MIS 21g, and MIS 20, while the most pronounced minima (epifauna) and maxima (infauna) occur during MIS 27, MIS 25e, MIS 22c, and MIS 22a. The deep-infauna taxa (Fig. 3b) exhibit a general increase in percentages from MIS 28 to MIS 22, ranging from 14 % to 0 %.

Figure 3Epibenthic δ18O record and benthic foraminiferal relative abundances and selected ecological groups at IODP Site U1387. (a) Relative abundances of the 10 most dominant species across the studied interval. (b) Ecological groupings and additional species of paleoenvironmental significance. Magenta curves indicate species primarily associated with food flux. Blue curves represent species indicative of well-oxygenated or ventilated water conditions. Purple curves highlight species of special interest in this study.

Regarding the shell types of benthic foraminifera, the relative abundances of porcelaneous taxa constitute an average of 4.3 % for the entire interval, while agglutinated taxa account for 3.5 %. The abundances of the porcelaneous group (Fig. 3b) were higher, particularly during glacial periods, with a notable increase of 15.2 % recorded during MIS 24. In contrast, lower percentages were observed during the warmer climate intervals (e.g. MIS 25, MIS 21, MIS 19). Notably, some intervals within MIS 24 and MIS 22 show relative abundances close to 0 %. The abundance of the agglutinated group (Fig. 3b) exhibits distinct variability, with generally higher percentages during interglacial periods such as MIS 21g and MIS 19c but also in MIS 26 and in some intervals of MIS 24 and MIS 20. Lower percentages are recorded during MIS 27, MIS 25e, and MIS 22b in particular.

One striking feature is the absence of H. balthica (Fig. 3a), which begins at the onset of MIS 24 and continues until the beginning of MIS 21. The highest percentages are observed during interglacial periods, particularly MIS 27, MIS 25e, MIS 21g, and MIS 19c, with the maximum abundance occurring during the interstadial MIS 28b. In contrast, during glacial periods, its abundance declines sharply, or it is completely absent. For instance, when δ18O values increase abruptly at the onset of MIS 24, H. balthica disappears completely. Conversely, as δ18O values decrease at the onset of the interglacial MIS 21g, it becomes more abundant again. Similarly, during the stadial MIS 21f and glacial MIS 20, its abundance drops to nearly 0 %.

It is also worth noting that certain species exhibit similar or contrasting patterns of abundances such as Bulimina striata subsp. mexicana on one hand, and Bolivinita quadrilatera and Bolivina alata (Fig. 3b) on the other hand. B. striata subsp. mexicana reaches up to 8 % relative abundance during MIS 27, MIS 25, MIS 21, and MIS 19, intervals when B. quadrilatera and B. alata are generally absent or occur in very low percentages. In contrast, during MIS 28, MIS 23, and MIS 22, when B. striata subsp. mexicana is less abundant, B. quadrilatera and B. alata tend to show higher abundances.

At Site U1387, the Stilostomella group comprises Stilostomella spp. and Mucronina advena (Fig. 3b). The extinction of Stilostomella spp. is recorded at 203.08 c-mcd, with an estimated age of 780 ka, whereas Mucronina advena disappears at 203.90 c-mcd, with an estimated age of 788 ka. Notably, these extinction events occur earlier than previously reported (e.g. Hayward et al., 2012; Kender et al., 2016), likely because our most recent sample dates to 760 ka, which may explain the absence of these taxa in younger intervals.

Benthic foraminifera diversity is generally moderate (Fig. 4f), with an average Shannon index of 3.1. The values range from 1.8 (MIS 21) to 3.8 (MIS 24). Relatively large fluctuations in diversity are observed during older periods, from MIS 28 to the end of MIS 22. Low values are observed mainly during warmer climate periods (e.g. MIS 28b, MIS 27, MIS 25e, MIS 25a, MIS 22c). From the beginning of MIS 21 onward, the fauna becomes more diverse, with values ranging between 2.6 to 3.6.

4.3 Organic matter, elemental composition, and wt % sand

The TOC and total alkenone concentration datasets exhibit similar trends (Fig. 4d, e), reflecting variations in organic carbon preservation and primary productivity. Both parameters show higher values during interglacials (e.g. MIS 27, MIS 25e, and MIS 21g) and interstadial sub-stages (e.g. MIS 28b, MIS 25c). In contrast, lower values are observed during the glacial periods and during stadial sub-stages (e.g. MIS 28a, MIS 23b, MIS 21d, MIS 19b).

Figure 4(a) Precession and obliquity (Laskar et al., 2004). IODP Site U1387 records of (b) epibenthic δ18O record, (c) epibenthic δ13C record, (d) total organic carbon (TOC) showing enhanced organic matter input during period of increased productivity, (e) total alkenone concentrations indicating coccolithophorid productivity, (f) Shannon diversity index, and (g) estimated dissolved oxygen using species microhabitat preferences. Light-blue bars indicate intervals of low-oxygen conditions at IODP Site U1387.

Similarly to the trends in the epibenthic δ13C data, the ln () record shows higher values during glacial lower-sea-level-stand periods and lower values during interglacial higher sea level stands (Fig. 5e). Additionally, higher values are associated with several stadials (e.g. MIS 28c, MIS 24c, MIS 24a, MIS 22a, MIS 22c, MIS 20a), indicating episodes of intensified bottom current activity. Millennial-scale variations are also observed in the wt % sand (> 63 µm) record. The highest values occurred during stadial sub-stages MIS 25d and MIS 21f, with peaks of 16 % and 12 %, respectively. Additional wt % sand (> 63 µm) maxima were recorded during the stadial sub-stages MIS 28a, MIS 23b, MIS 21a, and MIS 19b (Fig. 5g).

Figure 5(a) Precession and obliquity (Laskar et al., 2004) and IODP Site U1387 records of (b) planktic δ18O of G. bulloides, used for stratigraphic reference (Voelker et al., 2025a); (c) epibenthic δ18O; (c) epibenthic δ13C, revealing MOW ventilation; (e) ln() ratio; (f) relative abundance of elevated epibenthos group (> 250 µm); (g) weight percentage of sand (> 63 µm); (h) total abundance of P. ariminensis (# g−1) in the fraction > 125 µm; and (i) total benthic foraminifera abundance (# g−1). Higher values in (e)–(h) indicate a stronger bottom current. Grey bars highlight concomitant peaks of wt % sand and total P. ariminensis abundance.

4.4 Bottom current velocity and bottom water oxygenation indicators

The percentages of the elevated epibenthos group (Fig. 5f) show significant variability within each MIS, with maximum values reaching nearly 55.5 % during MIS 22 and minimum values of 0 % during MIS 25. Consistently high values are observed during colder climate periods. As expected, P. ariminensis (Fig. 5h) shows abrupt increases in total abundance (above eight specimens per gram) during the stadial sub-stages MIS 28a, MIS 25d, MIS 21f, and MIS 21b but also during the interstadial sub-stage MIS 21a. Notably, all of these abrupt increases coincide with peaks in the wt % sand (> 63 µm) (Fig. 5g). Most of the P. ariminensis total abundance maxima coincide with total benthic foraminifera abundance (Fig. 5i). Dissolved oxygen levels (Fig. 4g) showed substantial variability over time and ranged from 0.9 to 3.5 mL L−1. High values were reconstructed for MIS 28a, MIS 26, MIS 24, MIS 23b-a, and MIS 22b, with relatively stable concentrations above 2 mL L−1 for MIS 21 to MIS 19. MIS 28b, MIS 27, MIS 25e, MIS 25c, MIS 23c, and MIS 22c-a exhibited low values around 1 mL L−1.

4.5 Principal component analysis

For the multivariate statistical analyses, only species with relative abundances greater than 2 % were considered. The Q-mode PCA, which focuses on identifying co-variation among samples and reducing noise by describing the shared variance of dominant taxa rather than treating each one in isolation revealed four main assemblages accounting for 78.7 % of the total variance (Table S1, Fig. 6a). This approach extracts dominant gradients that integrate various taxa simultaneously, converting parallel abundance patterns into a single metric that can be linked to environmental parameters. Generally, we considered loadings of ≥ 0.4 to be significant and loadings of ≥ 0.8 to be dominant and scores between 1 and 3 to be significant and scores of ≥ 0.3 to be dominant species of the assemblage. The communality values, which indicate how well each sample is represented by the respective model, varied between 0.9 and 0.1 (0.8 on average).

The C. laevigata fauna (Q-mode PC1) varies significantly throughout the studied interval, with higher loadings generally restricted to glacial intervals with little additional influence in MIS 28b, MIS 27, and MIS 23b. Q-mode PC2, dominated by H. balthica (Table S1) and C. pachyderma, is particularly evident during MIS 28 to MIS 24 and the interglacial MIS 21g and MIS 19c, and loadings decrease from MIS 24 to MIS 22. The M. affinis and G. subglobosa fauna (Q-mode PC3) exhibit moderate variability throughout the interval, with higher values during short intervals in MIS 25, MIS 23, and MIS 21–MIS 19 and the lowest loading values in short intervals in MIS 28b, MIS 27, MIS 25e, MIS 25a, MIS 23c, and MIS 22c. The U. celtica fauna (Q-mode PC4) reveals the most pronounced variability through time among the Q-mode components, showing prominent peaks during MIS 25e and MIS 21e and generally lower values during MIS 28b and MIS 22.

The R-mode PCA, which considers abundant and rare taxa with similar fluctuations, also exhibits four main assemblages representing 22.4 % of the total variance (Table S1, Fig. 6b). Despite its low explained variance, our objective with this approach was to identify underlying ecological patterns and to isolate coherent groupings that are often masked by abundant taxa. We considered loadings of > 0.4 or to be significant. The R-mode PC1 is more restricted to the glacial intervals, mainly during MIS 24–MIS 22, with minor influence during MIS 28a, MIS 26, and MIS 20. The R-mode PC2 presents higher score values during MIS 28b, MIS 27, MIS 25e, MIS 25a, MIS 23c, MIS 22, and MIS 20. The R-mode PC3 is highly variable throughout the entire interval but presents higher score values, mainly during MIS 22. The R-mode PC4 exhibits more influence during MIS 25a and MIS 21b.

5.1 Ecological significance of the benthic foraminiferal assemblages

To better understand the environmental conditions represented by the extracted PCs (i.e. species assemblages), we have analysed the ecological preferences of the dominant and significant species contributing to each principal component and other relevant species (Table 1). This allows us to identify the parameters most likely governing the structure of the foraminifera assemblages across the studied interval.

Table 1Microhabitat and ecological preferences for the 10 most abundant benthic foraminifera species and the corresponding bibliographic references. (OM denotes organic matter). References with * mark fossil-based studies.

The Q-mode PCA revealed four dominant assemblages (Fig. 6a). PC1 is dominated by C. laevigata, a species associated with environments with high food availability (Mackensen et al., 1995) and where oxygen levels remain sufficiently high (Gussone and Filipsson, 2010). It is part of a fauna that seems to be restricted to glacial time periods (e.g. MIS 24, MIS 22, and MIS 20).

Q-mode PC2, primarily characterized by high loadings of H. balthica, exhibits a behaviour inversely related to that of Q-mode PC1, dominated by C. laevigata. Specifically, as PC2 loadings increase, PC1 loadings decrease, suggesting a decoupling in species associations (Fig. 6a). H. balthica is commonly used for paleoclimatic reconstructions in the Mediterranean Sea (Spezzaferri and Yanko-Hombach, 2007). This opportunistic species is associated with cooler waters, is tolerant of a broad range of oxygen levels, and generally shows higher abundances during periods of increased primary productivity (Fontanier et al., 2002, 2008b; Hess and Jorissen, 2009; Rosenthal et al., 2011; Ross, 1984; Schmiedl et al., 2003; Spezzaferri and Yanko-Hombach, 2007). Although often described as an epifaunal species, typical of well-oxygenated environments (Fontanier et al., 2002; Schmiedl et al., 2000), the other dominant species of Q-mode PC2, C. pachyderma, can shift to a shallow infaunal habitat depending on food availability (Licari, 2006; Wollenburg et al., 2018). This indicates an adaptation to varying oxygen conditions. In our record, Q-mode PC2 exhibits higher abundances throughout the interval but declines between MIS 24 and MIS 22. Simultaneously, Bulimina striata subsp. mexicana also declines. In deep-sea environments off West Africa, B. mexicana responds to increased organic matter content rather than to specific oxygen levels (Licari et al., 2003) but is typically rare in severely dysoxic or anoxic environments (Licari et al., 2003; Schmiedl et al., 1998, 2000). On the other hand, increased abundances between MIS 24 to MIS 22 are observed in Bolivinita quadrilatera and Bolivina alata species (Fig. 3b). B. quadrilatera has been associated with high primary productivity accompanied by sustained organic matter fluxes (Gupta and Satapathy, 2000) as a result of increased river runoff (Romahn et al., 2015), and it is often more abundant during glacial periods (Guo et al., 2017).

Bolivina alata indicates severely reduced bottom water oxygenation (den Dulk et al., 2000). Together, these ecological observations suggest that organic matter fluxes were not interrupted or reduced during MIS 24 to MIS 22. Instead, shifts in the quality of organic matter (e.g. labile vs. refractory) combined with changing bottom water oxygen conditions led to the observed changes in Q-mode PC1.

Melonis affinis, dominating Q-mode PC3, inhabits mesotrophic to eutrophic environments with a moderate flux of organic matter (Corliss, 1985; Harloff and Mackensen, 1997; Jorissen et al., 1995; Schmiedl et al., 2000). This species tends to be rare or even absent under highly eutrophic or dysoxic conditions (Fontanier et al., 2002), as well as in environments of extremely low-quality organic matter (Licari et al., 2003). Another significant species of Q-mode PC3 is G. subglobosa that is associated with low to intermediate fluxes of organic material and is generally abundant in oligotrophic, well-ventilated environments in the Atlantic Ocean, influenced by strong bottom currents (De and Gupta, 2010; Mackensen et al., 1995; Schmiedl and Mackensen, 1997).

Q-mode PC4, which is dominated by U. celtica, is suggested to be related to episodic surface ocean productivity pulses. Uvigerina celtica prefers labile organic matter (Schönfeld, 2006) or shifts in organic matter sources, as also indicated by the closely related U. peregrina (Koho et al., 2008). With high abundances in the Q-mode PC2 and PC4, these three species might suggest periods of maximum fluxes of fresh, labile organic carbon, in agreement with the high phytoplankton productivity reflected in the high total alkenone concentrations (Fig. 4e).

Figure 6Temporal variability of principal components of benthic foraminifera assemblages alongside epibenthic δ18O record and Shannon index at Site U1387: (a) Q mode and (b) R mode. Magenta curves indicate principal components primarily associated with food flux. Blue curves represent species indicative of well-oxygenated or ventilated water conditions. Shaded areas in the Q- and R-mode curves of both panels highlight intervals of statistically significant loadings and scores.

The species contributing to the R-mode PC1 (Fig. 6b) are mostly porcelaneous and hyaline taxa with an epifaunal to shallow infaunal microhabitat, including T. angulosa and G. subglobosa. The majority of R-mode PC1 species are adapted to well-oxygenated conditions, likely associated with intensified current velocity. The species associated with R-mode PC2, including B. irregularis, B. striata subsp. mexicana, and M. affinis, do not tolerate extremely low oxygen levels but are positively related to the deposition of labile organic material (Fontanier et al., 2008b; Schmiedl et al., 2000). The R-mode PC3, characterized by species such as T. angulosa, is interpreted to reflect the combined influences of stronger bottom currents and enhanced organic matter supply under stable, well-oxygenated conditions (Harloff and Mackensen, 1997; Mackensen et al., 1995).

Compared with other R-mode components, R-mode PC4 shows less distinct patterns but variability in its scores, likely reflecting food flux changes throughout the record, with higher values implying enhanced flux. Such an interpretation aligns with observations from the southwestern Portuguese margin, where the S. bulloides assemblage is associated with elevated primary productivity (Guo et al., 2021).

To summarize, the Q-mode principal components primarily reflect variations associated with the quality and quantity of food, with secondary influences of oxygenation, whereas the R-mode principal components primarily reflect variations driven by bottom water ventilation and oxygenation.

In addition to the general patterns identified through the PCA, several species display distinct distribution changes likely linked to seasonal variability in productivity. For instance, B. aculeata reaches maximum abundance during interglacial MIS 25e (Fig. 3a). This species is typically found in highly productive, low-oxygen environments with seasonal organic matter deposition (Jannink et al., 1998; Schmiedl et al., 2000). S. bulloides, similarly associated with high primary productivity and elevated organic carbon fluxes (Gooday, 2003; Schönfeld, 2002b), also shows an abundance maximum in MIS 25e shortly after the maximum observed for B. aculeata (Fig. 3a). These species successions may be influenced by variations in phytoplankton communities (e.g. diatoms vs. coccolithophores), species competition, or varying oxygen levels.

Globobulimina affinis, Globobulimina turgida, and Chilostomella ovoidea are typically part of the deep infauna, adapted to suboxic–dysoxic environments and become more abundant with reduced oxygen availability (Jorissen, 2003; Jorissen et al., 1995). The abundance of this species group increases from the onset of MIS 28 and varies over time but remains relatively high until the end of MIS 22 (Fig. 3b). These conditions were similarly associated with reduced diversity and the dominance of a few opportunistic, low-oxygen-tolerant species. Baas et al. (1998) also recorded maxima of G. affinis and C. ovoidea during intervals of inferred oxygen depletion on the Portuguese margin.

Porcelaneous taxa at our site represent cosmopolitan deep-sea taxa. Despite this, porcelaneous taxa are likely to be more tolerant of high-salinity conditions, as known from hypersaline seas (e.g. glacial Red Sea) and shallow-water environments (Badawi et al., 2005; Murray, 2014). This tolerance can lead to rises in relative abundance under higher-salinity conditions; thus, these taxa have been used as an indicator for deep-water salinity (Badawi et al., 2005; Halicz and Reiss, 1981; Locke and Thunell, 1988). At Site U1391 (Guo et al., 2017) and in the Red Sea (Badawi et al., 2005), the increase in porcelaneous taxa abundance during glacial intervals is interpreted as reflecting more saline bottom water. Furthermore, a higher abundance of the taxa is observed under well-oxygenated conditions (Kaiho, 1994, 1999). At our site, their average relative abundance is about 4 %, increasing up to 15 % during glacial periods, mainly during MIS 24 and MIS 22 (Fig. 3b). Porcelaneous taxa increase during those periods, indicating the presence of both more saline and well-oxygenated bottom water at Site U1387. The strong inverse relationship between taxa indicative of well-ventilated bottom waters (e.g. elevated epibenthos, epifauna, and porcelaneous groups) and those associated with food-enriched and suboxic conditions (infauna and deep-infauna) suggests that bottom water ventilation and trophic conditions at Site U1387 are controlled by MOW dynamics (Fig. 3b) (see Sect. 5.3), consistently with the finding by Singh et al. (2015).

Besides the species already discussed here, P. ariminensis exhibits trends in our record that are relevant to address due to its reliability for tracing MOW in the past. Rogerson et al. (2011) showed that variation in the relative abundances of P. ariminensis can be used to distinguish hydrodynamically distinct sectors of the MOW plume. In the Gulf of Cadiz, its occurrence is confined to the northern sector, where MOW-related bottom current activity is strongest (Rogerson et al., 2011). Ecologically, this taxon belongs to the elevated epibenthos group due to the preference of living in elevated substrates to capture suspended food and is generally attached to hard particles (e.g. sponge skeletons, stones) (Lutze and Thiel, 1989; Schönfeld, 1997, 2002a, b). Geochemically, P. ariminensis tends to calcify at approximately isotopic equilibrium with ambient seawater and exhibits δ13C and δ18O values that closely track the MOW signal, supporting its use as a robust MOW indicator (García-Gallardo et al., 2017b; Guo et al., 2017; Rogerson et al., 2011) (see Sect. 5.3).

5.2 Oxygen levels and productivity in the intermediate-depth Gulf of Cadiz

As discussed in the previous subsection, the distribution, abundance, and diversity of benthic foraminifera from Site U1387 reveal clear variations in bottom water oxygenation and organic matter fluxes during the EMPT, reflecting changes in primary productivity, bottom water ventilation, and organic matter quality delivered to the seafloor. Overall, oxygen level and productivity variations exhibit orbital-scale precession (insolation)-related forcing and sub-orbital variability linked to stadial (cold) and interstadial (warm) climate states.

Colder climate periods, such as stadials MIS 28a, MIS 25d, MIS 23b, MIS 21f, and MIS 19b and all glacial intervals, were dominated by epifaunal species and elevated porcelaneous taxa (Fig. 3b), along with higher faunal diversity during stadials (Fig. 4f). They are generally linked to precession maxima (insolation minima) and reflect well-oxygenated bottom waters and nutrient-poor waters (Fig. 4a). These findings are consistent with observations at the same site from younger intervals (MIS 7 to MIS 5; Singh et al., 2015) and the Early Pliocene (García-Gallardo et al., 2017a). The latter authors linked this species group to improved oxygenation and reduced food supply, associated with the establishment of the Mediterranean–Atlantic water exchange. Enhanced ventilation during stadials has been reported in the Gulf of Cadiz (Bahr et al., 2014; Voelker et al., 2006) and the Mediterranean Sea, where Western Mediterranean Deep Water (WMDW) was well-oxygenated during cold phases (Cacho et al., 2006; Jiménez-Espejo et al., 2015). The increased oxygenation has been attributed to intensified cold and dry northwesterly winds that enhanced the formation of WMDW in the northern part of the basin (Cacho et al., 2006; Mesa-Fernández et al., 2022).

The lowest oxygen contents are suggested for periods of precession minima (insolation maxima) characterized by low epibenthic δ13C values, decreased diversity, increased infaunal abundances, and lower percentages of epifaunal and porcelaneous taxa during interstadials (e.g. MIS 28b, MIS 25a and c) and during interglacials (e.g. MIS 27, MIS 25e) (Figs. 4a, c, and f and 3b). Such conditions favour species feeding on refractory organic material within the sediment (e.g. Caralp, 1989; Fontanier et al., 2002, 2013; Jorissen et al., 1995). The increased abundance of deep-infauna taxa between MIS 28 to MIS 22, together with pronounced variability in foraminifera diversity and dissolved oxygen estimates (Kranner et al., 2022), supports a scenario of unstable bottom water conditions (Figs. 3b and 4f and g). Periods of reduced diversity align with reduced ventilation intervals, reinforcing the interpretation that changes in oxygen levels were relevant in shaping the regional benthic foraminifera community structure.

Similar patterns characterized by infaunal dominance and low diversity have been linked to mesotrophic to eutrophic conditions during reduced ventilation in the Gulf of Cadiz (García-Gallardo et al., 2017a; Singh et al., 2015). Similarly, Caralp (1988) and Baas et al. (1998) both associated increased abundances of deep-infaunal taxa with low-oxygen conditions accompanied by elevated organic matter flux. These findings support the use of deep-infaunal taxa and low epibenthic δ13C values as indicators of suboxic to dysoxic conditions at Site U1387. On the southwestern Portuguese margin, Guo et al. (2017) also investigated the relationship between benthic foraminifera and bottom water oxygenation. However, methodological differences may explain some divergent interpretations. Guo et al. (2020a, 2017) analysed the > 250 µm size fraction, which can potentially underrepresent smaller infaunal species. In contrast, our study also includes the 250–125 µm fraction, where most infaunal taxa are abundant. Nevertheless, Guo et al. (2017) likewise associated infaunal taxa with low-oxygen, high-organic-flux conditions, consistently with reduced bottom water ventilation. Unlike our study, Guo et al. (2017), García-Gallardo et al. (2017a), and Singh et al. (2015) do not incorporate independent productivity proxies (e.g. total alkenones concentration and TOC), limiting the robustness of their interpretations regarding organic matter delivery to the seafloor.

The enhanced primary productivity, reflected in the increased TOC and total alkenone concentrations during the interstadial MIS 28b and the interglacials MIS 27 and MIS 25e may suggest that bottom water oxygen depletion was driven by both reduced ventilation and elevated surface productivity (Fig. 4d, e) (Gooday et al., 2000; Villanueva et al., 1998). Although epibenthic δ13C values do not directly quantify oxygen levels, they reflect oxygen consumption during organic matter remineralization (Kroopnick, 1985). In addition to elevated TOC and total alkenone concentrations, elevated numbers of resting spores of the high-productivity-related diatom species Chaetoceros were also observed during warm climate phases, e.g. MIS 28b (referred to as MIS 27b in Ventura et al., 2017) and MIS 25e at the same site. These intervals coincide with maximum abundances of B. aculeata and S. bulloides, suggesting enhanced surface water productivity exported to the seafloor (Fig. 3a). While both species display other periods of relatively high abundance throughout the studied interval, the lack of diatom assemblage data during some periods limits further interpretation.

Periods of reduced TOC and total alkenone concentration might reflect a reduced carbon deposition rather than a decline in surface productivity. This scenario is observed during glacial periods (e.g. MIS 24, MIS 22) and stadial sub-stages (e.g. MIS 28a, MIS 23b, MIS 21d, MIS 19b). At Site U1387, low concentrations may reflect enhanced degradation of organic matter before its burial under well-ventilated bottom waters, which promote remineralization and reduce the amount of TOC preserved in the sediment (Burdige, 2006; Calvert and Pedersen, 1992; Hartnett et al., 1998). A similar mechanism has been observed in the Early Pleistocene record at Site U1387, where water column stratification and vertical mixing strongly influenced coccolithophore accumulation (Trotta et al., 2022). Therefore, we propose that comparable environmental conditions occurred during MIS 24 to MIS 22, when we observe increased Q-mode PC1 loadings (C. laevigata) despite low TOC and total alkenone concentrations, along with evidence of enhanced bottom water ventilation (Figs. 4c–e and g and 6a), with the exception of the stadial phases of MIS 22.

Primary productivity may also have been stimulated by micronutrients provided by dust deposition due to the increased aridity and wind strength during glacial periods (Bout-Roumazeilles et al., 2007; Moreno et al., 2006; Voelker et al., 2015). Similar aeolian fertilization mechanisms have been suggested for the last glacial in the Gulf of Cadiz (Penaud et al., 2022), supporting the hypothesis that dust may have also indirectly sustained benthic productivity. This is further supported by increased concentrations of terrestrial biomarkers and terrestrial organic matter during colder sea surface temperature (SST) intervals at Site U1387, indicating enhanced atmospheric delivery of continental material (Voelker et al., 2015). Besides aeolian and upwelling-driven productivity, nutrient inputs from the Guadiana and Guadalquivir rivers may also have contributed to regional fertilization (Caralp, 1988; Moal-Darrigade et al., 2022; Voelker et al., 2015). The complex interaction of different environmental drivers of surface water productivity explains why phases of enhanced food fluxes, along with shifts in food quality (e.g. marine vs. terrestrial, labile vs. refractory composition), occurred during both glacial and interglacial periods.

Within this framework, the two stadial phases of MIS 22 represent special cases. During those periods, we observed higher Q-mode PC1 loadings (C. laevigata) together with low TOC and poor ventilation (Figs. 3a, 4d, and 5d). These are periods when the lower SSTs (Fig. 7d) and maxima in Neogloboquadrina pachyderma relative abundance at Site U1387 indicate the presence of colder, less saline surface waters, consistently with extreme North Atlantic cooling events during glacials and stadials (e.g. Hodell et al., 2023; Mega et al., 2025; Trotta et al., 2025). These (subpolar) surface waters likely enhanced water column stratification as observed during the Heinrich events of the last glacial cycle (Colmenero-Hidalgo et al., 2004) and might have promoted the recycling of organic matter in the upper water column and thus a reduced carbon export to the seafloor.

This study reinforces the importance of combining faunal assemblage data and epibenthic δ13C and productivity-related data to interpret the environmental dynamics at the seafloor. While the dissolved oxygen estimates correlate well with these indicators, they should still be interpreted with caution. As noted by Schmiedl et al. (2023), the Enhanced Benthic Foraminiferal Oxygen Index (EBFOI) is based on benthic foraminifera microhabitat preferences, which can vary depending on regional or environmental conditions. For example, U. celtica has been designated as oxic species by Schönfeld (2001) yet has been classified as suboxic by Kranner et al. (2022), while the microhabitat preferences of C. pachyderma also remain debated. To address this issue, future reconstructions should incorporate additional independent redox proxies, such as trace element ratios, to improve the robustness of oxygenation reconstructions in different settings.

Our results indicate that bottom water oxygenation and organic matter fluxes at Site U1387 during MIS 28 to MIS 19 were largely governed by local oceanographic dynamics rather than glacial–interglacial cycles. Low-oxygen phases are consistently associated with enhanced productivity and a shift toward refractory organic matter delivery, particularly during MIS 24 to MIS 22. Reduced benthic foraminiferal diversity during these intervals acts as an indicator for stressed conditions. In contrast, from MIS 21 to MIS 19, the data reveal a gradual improvement in bottom water ventilation and a stable seafloor environment, supporting the persistence of a diverse benthic foraminiferal assemblage (Fig. 4c, f, and g).

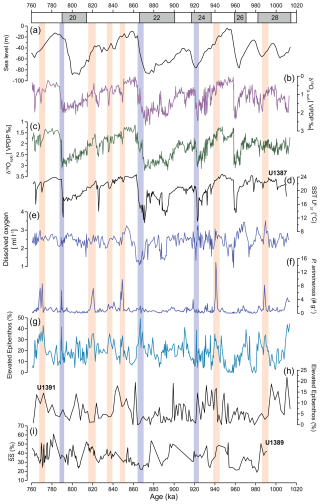

5.3 Mediterranean Outflow Water variability and bottom current strength

The sedimentological, geochemical, and micropaleontological records from Site U1387 demonstrate a considerable variability of bottom current strength across the EMPT, driven by both orbital and millennial-scale climatic forcing. These changes are documented by sedimentological proxies, including ratios and sand content (Fig. 5e, g), as well as by the relative abundance of the elevated epibenthos group (Figs. 5f and 7g), the absolute abundance of P. ariminensis (Figs. 5h and 7f), and PCA-derived R-mode component scores (Fig. 6b).

5.3.1 MOW at orbital timescales

At orbital timescales, bottom current intensity strongly corresponds with glacial–interglacial variability. It is modulated by precession as indicated by an inverse correlation with insolation (Fig. 5a). The epibenthic δ13C, ratio, proportions of the elevated epibenthos group, and scores in R-mode PC1 records from Site U1387 (Figs. 3b and 5d–f) indicate stronger bottom current activity during precession maxima (insolation minima), particularly evident during the glacial stages. Phases of enhanced bottom current activity were associated with increased ventilation and oxygenation (see Sect. 5.2) and are interpreted to reflect a stronger influence of Mediterranean-derived waters. This interpretation aligns with the findings of previous studies on MOW dynamics in the Gulf of Cadiz (García-Gallardo et al., 2017a; Voelker et al., 2006, 2015; Singh et al., 2015).

Higher epibenthic δ13C values during glacial periods, supported by our other evidence of improved oxygenation (Fig. 4), indicate the influence of a younger and better-ventilated water mass contributing to the MOW (Singh et al., 2015). Among MOW sources, WMDW plays an important role. It has been suggested by Voelker et al. (2006) that phases of increased MOW activity were associated with periods of enhanced convection in the western Mediterranean Sea. Higher (epi)benthic δ13C values showed that both Mediterranean water masses contributing to the outflow across the Strait of Gibraltar were better ventilated during glacial MIS 2 and the Greenland stadial phases of MIS 3, i.e. the WMDW (Cacho et al., 2006; Frigola et al., 2008), as well as the Levantine Intermediate Water (Toucanne et al., 2012). Despite the progressive sea level lowering during the glacials (Elderfield et al., 2012; Rohling et al., 2014, 2021) (Fig. 7a), restricting the exchange of water through the Strait of Gibraltar, Mediterranean-sourced waters continued to flow into the Gulf of Cadiz under glacial conditions, as observed in records from the western Iberian margin (Schönfeld and Zahn, 2000) and in the Gulf of Cadiz (e.g. McCave, 2023a; Rogerson et al., 2005; Voelker et al., 2006, 2015). Independent evidence from the sortable silt record of Site U1389 (644 m water depth; Fig. 1) further demonstrates sustained high flow despite a restricted exchange at the Gibraltar sill during glacial lowered sea levels (Fig. 7i) (McCave, 2023a).

Figure 7(a) Sea level relative to present (Rohling et al., 2021). (b) Planktic δ18O of G. bulloides of Site U1387 (Voelker et al., 2025a). (c) Epibenthic δ18O record (this study). (d) Alkenone-derived SSTs of Site U1387 (Voelker et al., 2025b). (e) Estimated dissolved oxygen. (f) Total abundance of P. ariminensis (this study, > 125 µm fraction). (g) Relative abundance of elevated epibenthos group (this study, > 250 µm fraction). (h) Relative abundance of elevated epibenthos of Site U1391 (Guo et al., 2020b; > 250 µm fraction). (i) Sortable silt ( %) of Site U1389 (McCave, 2023b). Orange bars indicate periods of increased bottom current velocity during falling sea levels, whereas bluish bars mark increased velocities associated with terminal stadial events. Possible age offsets with Sites U1389 and U1391 should be considered within the limitations of their respective age models.

In our record, increased δ13C, , and elevated epibenthos groups coincide with higher proportions of porcelaneous taxa (see Sect. 5.1). This may indicate higher salinity and, thus, the presence of a denser water mass. So, based on the Site U1387 evidence, the upper MOW acted as an intensified bottom current on the central Faro drift during glacials, leading to higher sedimentation rates (Fig. S1c).

Periods of reduced MOW intensity are marked by lower epibenthic δ13C, a decreased ratio, low elevated epibenthos group percentages, and a low influence of the R-mode PC1 assemblage (Figs. 5d, e and f and 6b). These characteristics are accompanied by a decrease in the porcelaneous group and diminished abundances of species typically associated with well-oxygenated conditions and point to transient phases of poor ventilation and weakened MOW influence (Fig. 3b). These conditions generally occur during precession minima and insolation maxima, typically during interglacial periods, and are associated with δ13C minima (Fig. 4a and c) (Voelker et al., 2015). Insolation maxima have also been related to sapropel formation in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, driven by an intensification of the North African Monsoon, which led to increased precipitation and freshwater input into the eastern Mediterranean Sea (Emeis et al., 2000; Grant et al., 2022). Similarly, pollen-based climate reconstructions from the western Mediterranean region during the EMPT show warmer and wetter conditions during interglacials (Joannin et al., 2011), which reinforces the evidence of regional humidity. More humid conditions could have influenced the study area by means of increased discharge from the Guadiana and Guadalquivir rivers, delivering nutrient-rich freshwater to the ocean and promoting primary productivity (see Sect. 5.2), which, in turn, enhanced organic remineralization and contributed to negative excursions in δ13C, and/or by reducing WMDW influence in the in the Alboran Sea (Cacho et al., 2006; Frigola et al., 2008; Trotta et al., 2022; Voelker et al., 2006, 2015). A decrease in δ13C values and the elevated epibenthos group was also observed during MIS 7 to MIS 5 at Site U1387 (Singh et al., 2015).

Records from the lower MOW core depth range on the southwestern Iberian margin present a contrasting perspective compared to our Site U1387 data (Guo et al., 2017; Fig. 7h). Guo et al. (2017, 2020a) suggest an enhanced lower MOW flow during interglacial periods at Site U1391 (1085 m water depth; Fig. 1). This was recently corroborated by the grain size record of IODP Site U1588 (1339 m water depth; Fig. 1), which revealed a stronger lower MOW core flow during the interglacials of the last 250 kyr and during the interstadials MIS 5c and MIS 5a (Chen et al., 2025). For the glacial periods over the last 1.3×106 years, Guo et al. (2017, 2020a) reported higher abundances of miliolids (referred to here as porcelaneous taxa) at Site U1391, which they interpret as being indicative of a denser but sluggish MOW. One has to be careful, however, because the southwestern Iberian margin is strongly influenced by vertical migration of the MOW cores, including periods when Site U1391 was not influenced by MOW at all (Nichols et al., 2020). Nichols et al. (2020) also observed two types of regimes at Site U1391, i.e. orbital-paced changes in MOW conditions between MIS 6 and MIS 10 in contrast to millennial-scale changes during MIS 11 and from MIS 4 to MIS 1. This regime shift might explain why, at Site U1391, under the influence of a lower MOW core, Nichols et al. (2020) reported a sluggish MOW during the glacial periods and stronger MOW flow during interglacials of the late Pleistocene, which is in contrast to our EMPT record.

5.3.2 MOW at millennial timescales

In addition to orbital-scale changes, our results also reveal millennial-scale oscillations in bottom current intensity. Both the epibenthic and planktic δ18O records exhibit millennial-scale oscillations and thus rapid shifts in bottom and surface water temperature and circulation (Voelker et al., 2015; Mega et al., 2025), linked to suborbital-timescale climate dynamics in the North Atlantic (e.g. Hodell et al., 2023; McManus et al., 1999; Raymo et al., 1998). The link between North Atlantic cold-climate events and increased MOW velocity (contourite layer formation) in the Gulf of Cadiz is well documented for the late Pleistocene (e.g. Bahr et al., 2015; Kaboth et al., 2016; Llave et al., 2006; Sierro et al., 2020; Toucanne et al., 2007; Voelker et al., 2006).

At Site U1387, millennial-scale events of increased MOW velocity are indicated by the P. ariminensis absolute abundance, proportion of the elevated epibenthos group, sand content, , and δ13C records (Figs. 5 and 7). While all proxies indicate enhanced MOW strength, the ratio, elevated epibenthos group, and δ13C data reflect the complete evolution of flow velocity change, i.e. the gradual increase, the velocity maximum, and then the gradual decline, in agreement with the bi-gradational sequence model for contourite layer formation (Faugèers et al., 1984). P. ariminensis total abundance and sand content, on the other hand, mark only periods of maximum flow velocity.

In our record, we identified two distinct millennial-scale response types: (i) events linked to terminal stadial events (Hodell et al., 2015; Mega et al., 2025), when the thermohaline circulation was weakened (Fig. 7, bluish bars), and (ii) events linked to lowering sea level (Fig. 7, orange bars). The first type is marked by increases in planktic δ18O values, lower SSTs, and higher proportions of the elevated epibenthos group during the terminations of MIS 24/23, MIS 22/21, and MIS 20/19, with the absence of a response during the MIS 26/25 terminal stadial event (Fig. 7b, d, and g). Except for MIS 20/19, these events are recorded primarily in the epibenthos group rather than in P. ariminensis total abundance. They are also the stadial events when MOW ventilation was reduced, which might be related to conditions in the North Atlantic, especially during MIS 22 (Thomas et al., 2022). Records from the surface and deep waters of the North Atlantic region (e.g. Hodell et al., 2023) and the Gulf of Cadiz (Mega et al., 2025; Voelker et al., 2006) reveal that one of the major forces controlling millennial-scale variations is the thermohaline circulation. At Site U1385 (Fig. 1), Hodell et al. (2023) showed that millennial-scale fluctuations persisted throughout the EMPT, generally accompanied by colder SSTs (Rodrigues et al., 2017). Rogerson et al. (2012) postulated that the cold surface waters entering into the Gulf of Cadiz during glacials and stadials (and Greenland stadials of MIS 2 and MIS 3) led to a higher density gradient, with the relatively warmer MOW favouring increased bottom flow velocity.

Although the MOW's highest flow at Site U1387 coincides with high planktic δ18O values (Fig. 7b), those periods are not always associated with colder SSTs (Mega et al., 2025). This suggests that MOW changes during the EMPT were influenced by other factors, likely a combination of sea level changes and density-driven circulation (potentially due to salinity), and not by surface water cooling alone. The second type, associated with a lowering sea level, is represented by MOW velocity increases during several stadial phases (e.g. MIS 28a, MIS 25d, MIS 21f, MIS 19b) and during the interstadial MIS 21a (Figs. 5, 7). This pattern, typical of glacial and stadial intervals, is consistent with previous observations of contourite layer formation by intensified MOW velocity at Site U1387 (Moal-Darrigade et al., 2022; Voelker et al., 2015).

At Site U1387, well-ventilated conditions consistently accompanied all episodes of intensified MOW, a feature also reported by Voelker et al. (2015) from MIS 31 to MIS 29. This might be explained by the contribution of well-ventilated LIW and WMDM to the MOW (Cacho et al., 2000, 2006; Frigola et al., 2008; Toucanne et al., 2012).

The abrupt increases in the absolute abundance of P. ariminensis support the sensitivity of regional ventilation to MOW strength, as already discussed in previous studies (García-Gallardo et al., 2017a; Rogerson et al., 2011). We therefore propose the use of P. ariminensis abundance combined with the sand content or ratio as a robust proxy for identifying the peak bottom current activity. In cases where grain size data are unavailable, P. ariminensis may serve as an independent and qualitative indicator of strong MOW influence. However, it needs to be tested for other sediment cores bathed by upper and lower MOW during the EMPT.

This study provides the first high-resolution multiproxy reconstruction of seafloor environment and benthic ecological changes at Site U1387 during the EMPT (MIS 28 to MIS 19). By combining benthic foraminifera assemblages, stable isotope records, sedimentological proxies, and organic geochemical data, we show that bottom water conditions in the Gulf of Cadiz responded sensitively to both orbital- and millennial-scale climate variability. Principal component analysis further supports the fact that food supply, oxygen availability, and bottom water dynamics controlled the benthic foraminiferal assemblage structure. Species-specific ecological responses, such as the decrease in H. balthica during low-oxygen intervals and the dominance of C. laevigata, highlight the sensitivity of benthic ecosystems to environmental stress such as possible shifts in food quality.

Our results demonstrate that seafloor conditions at Site U1387 reflect a combination of local productivity and regional MOW conditions. Enhanced productivity as a result of either upwelling or riverine inputs increased organic matter delivery and remineralization at the seafloor, favouring low-oxygen-tolerant species. An intensified, better-ventilated MOW as the bottom current favoured epifaunal and porcelaneous taxa, as well as higher faunal diversity during glacials and stadials. In contrast, interglacial intervals with weaker MOW flow strength were more affected by local processes.

In summary, this research emphasizes that organic matter remineralization must be considered when interpreting benthic foraminifera and TOC records. In this context, combining epibenthic and deep-infaunal δ13C gradients offers a viable approach to assess remineralization and bottom water oxygenation. In addition, the absolute abundance of Planulina ariminensis (numbers per gram of sediment) proved to be a reliable proxy for tracking bottom current intensification during the EMPT.