the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Seasonal dynamics of mudflat foraminifera linked to diatom species and traits

Constance Choquel

Emmanuelle Geslin

Edouard Metzger

Bruno Jesus

Antoine Prins

Emilie Houliez

Magali Schweizer

Thierry Jauffrais

Éric Bénéteau

Aurélia Mouret

The trophic ecology of benthic foraminifera in intertidal mudflats is closely linked to diatoms, a dominant component of the microphytobenthos (MPB). Although experimental studies and metabarcoding have clarified foraminiferal diets, in situ assessments of the temporal dynamics of diatoms and foraminifera remain limited. In this study, we examined the seasonal dynamics of adult (> 150 µm) foraminiferal species over a notable 3.5-year monthly monitoring period at the La Coupelasse mudflat (Bay of Bourgneuf, French Atlantic coast). We related these dynamics to 25 environmental variables and to diatom assemblages, focusing on their traits (size, shape, and life-form). La Coupelasse exhibited a clear seasonal pattern driven by bay hydrodynamics, which regulated the availability of redox-sensitive metals, nutrients, and MPB biomass, thereby shaping the environmental context for benthic communities. Diatom traits, whether considered individually or in combination (“size + shape + life-form”), revealed distinct seasonal strategies that complemented species-level analyses. While species-level data provided a detailed understanding of foraminiferal temporal dynamics, combining diatom traits offered a more effective way to identify seasonal dietary shifts. The four dominant foraminiferal species occupied different seasonal niches, with Ammonia confertitesta and Haynesina germanica showing synchronized biannual peaks in spring and autumn, but differed in dietary responses, as H. germanica responded only to diatom shape. Elphidium oceanense displayed a single annual peak in early autumn, corresponding to a broader trophic flexibility across diatom traits, while Elphidium selseyense showed a late spring peak and remained enigmatic regarding its diatom food preferences. Overall, using combined diatom traits outperformed both species identity and MPB biomass in predicting foraminiferal patterns, highlighting their potential to simplify diatom–foraminifera trophic ecology by overcoming diatom taxonomic constraints. These findings shed light on our understanding of benthic ecology and suggest that trait-based approaches, when integrated with spatial and microbiome data, can enhance predictions of ecosystem responses to environmental change.

- Article

(8445 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(740 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Temperate intertidal mudflats are highly productive ecosystems, driven by photosynthetic microorganisms, such as diatoms (Bacillariophyceae, Haeckel, 1878; MacIntyre et al., 1996; Underwood and Kromkamp, 1999). These diatoms form dense biofilms on the upper sediment layers during daytime low tides, significantly contributing to the microphytobenthos (MPB) community (e.g., MacIntyre et al., 1996; Smith and Underwood, 1998; Decho, 2000; Méléder et al., 2003; Jesus et al., 2006). The spatial and temporal dynamics of diatom assemblages reflect seasonal variations. On the French Atlantic coast, especially in the Bay of Bourgneuf, they comprise 97 % of the MPB communities, highlighting their key role in these environmental settings (e.g., Méléder et al., 2007). These benthic diatoms exhibit various adaptive strategies to cope with environmental pressures like grazing, flow disturbances, nutrient availability, sediment type, temperature, and light intensity (Pinckney and Sandulli, 1990; Brotas et al., 1995; Underwood and Kromkamp, 1999; van der Grinten et al., 2005; Benyoucef et al., 2014). These adaptations give rise to diverse life-forms, including epipelic (benthic, with mobile cells), epipsammic (benthic, with sand-fixed cells), tychopelagic (both benthic and pelagic), and pelagic (true planktonic) forms (Round, 1965; Admiraal et al., 1984; Passy, 2007). Morphological traits of diatoms, such as frustule size and shape, are also critical in driving diatom succession, explaining seasonal variations in species dominance within specific environments (Kawamura and Hirano, 1992; Martínez De Fabricius et al., 2003; Litchman and Klausmeier, 2008; Sun et al., 2018; Kléparski et al., 2022; Laraib et al., 2023). Understanding the seasonal dynamics of morphological traits and life-forms in diatoms within MPB communities is crucial for elucidating ecological interactions in mudflat ecosystems. However, the impact of these seasonal diatom trait variations on higher trophic levels, especially benthic meiofauna such as foraminifera, remains inadequately explored (Lipps, 1983; Austin et al., 2005; LeKieffre et al., 2018).

Benthic foraminifera (Rhizaria; Cavalier-Smith, 2002) are marine unicellular eukaryotes that exhibit diverse and complex trophic strategies (Lopez, 1979; Murray, 2006). Both experimental and microbiome studies have highlighted the significant role of diatoms as a food source for common mudflat foraminifera species, particularly concerning the mode of ingestion and the size and shape of the diatoms (Austin et al., 2005; Pillet et al., 2011; LeKieffre et al., 2018; Chronopoulou et al., 2019; Schweizer et al., 2022; Jesus et al., 2022). The genus Ammonia is characterized by a highly adaptable feeding strategy, consuming various food sources, including diatoms when they are abundant (Pascal et al., 2009; Dupuy et al., 2010; Mojtahid et al., 2011; Jauffrais et al., 2018; LeKieffre et al., 2018; Wukovits et al., 2018; Chronopoulou et al., 2019; Schweizer et al., 2022). Haynesina germanica is a key model organism for studying active kleptoplasty in benthic foraminifera, i.e., the ability to retain chloroplasts from an algal source (Alexander and Banner, 1984; Clark et al., 1990; Jauffrais et al., 2016; Cesbron et al., 2017; Goldstein and Richardson, 2018; LeKieffre et al., 2018; Jesus et al., 2022). Its selective feeding behavior is closely tied to diatom size and shape, as H. germanica cracks the diatom frustule to extract cellular contents using its pseudopods (Austin et al., 2005; Jesus et al., 2022). Microbiome analyses highlight its dietary preference for medium to large elongated diatoms (Pillet et al., 2011; Chronopoulou et al., 2019; Schweizer et al., 2022). Within Elphidiidae, only Elphidium williamsoni has been conclusively shown to perform active kleptoplasty, while other species, such as Elphidium oceanense and Elphidium selseyense, lack direct evidence of this behavior despite hosting kleptoplasts (Lopez, 1979; Pillet et al., 2011; Jauffrais et al., 2018; Bernhard and Geslin, 2018; Jesus et al., 2022). Elphidium oceanense demonstrates a generalist feeding strategy, consuming diatoms of various sizes and morphologies supplemented by other prey when diatoms are scarce (Schweizer et al., 2022). Similarly, microbiome analysis of E. selseyense suggests an omnivorous diet that includes diatoms (Elphidium sp. S5; Chronopoulou et al., 2019).

The temporal dynamics of diatom and foraminifera assemblages in mudflats are widely recognized as indicators of seasonal environmental changes (e.g., Méléder et al., 2007; Debenay et al., 2006). However, in situ studies simultaneously addressing the dynamics of both groups remain scarce, primarily due to the challenges of co-sampling under identical environmental conditions and the distinct taxonomic expertise required for their identification. By advancing our understanding of diatom–foraminifera coupled assemblages, this study provides new insights into an understudied trophic level in mudflat ecosystems. In this context, the present study aims to enhance our understanding of the seasonal dynamics of mudflat foraminifera by examining environmental variables and the assemblage of diatom species, with a particular focus on their morphological traits (size and shape) and life-forms. Conducted at La Coupelasse, a mudflat in the Bay of Bourgneuf serving as a pilot site for long-term biomonitoring, we hypothesize that the four dominant foraminiferal species (Ammonia confertitesta, Haynesina germanica, Elphidium oceanense, and Elphidium selseyense) are characterized by distinct ecological niches and preferences for diatom food sources. The main objectives of this study were (1) to describe the seasonal environmental context in La Coupelasse mudflat, then (2) to characterize the seasonal dynamics of diatoms and foraminifera, and (3) to link diatom species and traits to seasonal patterns in foraminiferal species.

2.1 Site description

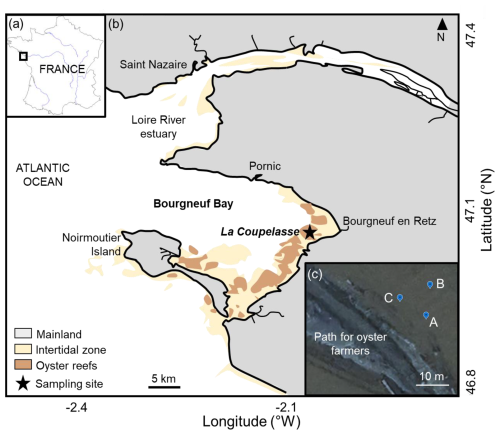

The Bay of Bourgneuf (46°52′–47°08′ N, 1°58′–2°20′ W) is situated on the French Atlantic coast, south of the Loire River estuary (Fig. 1a). This semi-enclosed bay, filled with freshwater channels, covers an area of 340 km2 and features a large intertidal mudflat of about 100 km2. It connects to the Atlantic Ocean through a passage located between the Loire River estuary and Noirmoutier Island (Fig. 1b). The sampling site was La Coupelasse (Fig. 1b), in the northern part of the Bay of Bourgneuf, known for its strong hydrodynamics (Debenay, 1978; Haure and Baud, 1995; Barillé-Boyer et al., 1997) and sandy mud sediment (Debenay, 1978; Service hydrographique et océanographique de la Marine – SHOM, https://www.shom.fr, last access: 14 January 2026). The three stations, A ( N, W), B ( N, W), and C ( N, W), located 10 m apart along a small tidal channel near a path used by oyster farmers, are considered to be replicates (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1(a) The Bay of Bourgneuf is situated on the French Atlantic coast. (b) On the southern side of the Loire River estuary, the sampling site La Coupelasse is marked with a star, and panel (c) highlights the three stations (A, B, C) along a path used by oyster farmers. Modified from Thomas et al. (2016).

2.2 Hydrological and meteorological variables

The monthly discharge of the Loire River (m3 s−1) was monitored at the Montjean-sur-Loire station, located approximately 120 km upstream from the Loire River estuary (http://www.hydro.eaufrance.fr/, last access: 14 January 2026). The tidal coefficient and the monthly air temperature (°C) were obtained from the weather station in Bourgneuf-en-Retz (Fig. 1) using information from SHOM.

2.3 Sediment sampling, processing, and analyses

One sediment core was collected per sampling at each station for geochemical analyses of pore water and solid phases. The cores, with an internal diameter of 10 cm, were transported to the laboratory in Angers and stored at in situ temperature for subsequent analyses the next day. To prevent oxygen contamination of the deeply reduced sediments, the cores were sliced in a nitrogen (N2)-filled bag. The cores were sectioned at 2 mm intervals down to a depth of 1 cm. The average of the first five 2 mm slices was used (i.e., corresponding to 1 cm slice thickness used for foraminiferal biomonitoring in Schönfeld et al., 2012). Each sediment slice was weighed and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 15 min. Pore water was filtered through 0.2 µm Minisart® RC25 cellulosic syringe filters and divided into three aliquots. One aliquot was used for dissolved nutrient colorimetric analyses (∑sum of ammonium, NH3 = NH3 + NH, and nitrate, NOx= NO + NO) and alkalinity. NOx concentrations were analyzed according to the Griess method (Hansen and Koroleff, 1999), with vanadium chloride serving as a nitrate reducer (Schnetger and Lehners, 2014; García-Robledo et al., 2014). The ∑NH3 was analyzed using the Berthelot method (Berthelot, 1859), adapted to small samples with variable salinity (Metzger et al., 2019). The second aliquot was used to measure pore water alkalinity through the colorimetric method of Sarazin et al. (1999). All spectrophotometric analyses were performed with a Genesys 20 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher). A third aliquot was acidified with a 1 % equivalent volume of concentrated HNO3 for ICP-AES analysis (Thermo Scientific iCAP 6300 Radial) after a 10-fold dilution with a 1 % HNO3 solution. Total silicium (Si), potassium (K), lithium (Li), calcium (Ca), barium (Ba), strontium (Sr), iron (Fe), phosphorus (P), manganese (Mn), and sulfur (S) were measured following the protocol for pore water analysis (Owings et al., 2019). Salinity was calculated from sodium (Na) measurements (details in Thibault de Chanvalon et al., 2015). The Redfield ratio N:P was also calculated (Tyrell, 1999).

The solid fraction was frozen and then freeze-dried. Porosity (Φ) was calculated from weight loss, assuming a particle density of 2.65 g cm−3 (Burdige, 2006), and a constant water density of 1 g cm−3 according to the following equation:

where mH2O and δH2O are the mass and density of water and msed and δsed are the mass and density of sediment (δsed=2.65 g cm−3), respectively.

Granulometric analyses were performed on the top centimeter of sediment collected from April 2017 to March 2019 at sampling stations A, B, and C. Measurements were done with a Malvern Mastersizer 3000 laser granulometer (LPG, Angers), and the data were analyzed using the RYSGRAN package in R (R Core Team, 2025). The median grain size (D50), defined as the particle size at which 50 % of the cumulative distribution occurs, was chosen as the main variable for this study. This measure is especially representative of skewed or non-uniform particle size distributions.

An additional core from station C was used to measure oxygen (O2) profiles with a microelectrode, enabling the quantification of oxygen penetration depth (OPD; mm) and dissolved oxygen uptake (DOU; nmol cm−2 s−1). Sediment oxygen profiles were measured the day after sampling in the laboratory in Angers under dark conditions to simulate aerobic mineralization, using a Clark electrode with a 50 µm tip diameter (Unisense, Denmark). A motorized micromanipulator enabled the measurement of O2 concentration profiles along the sediment core in 100 µm steps. Each oxygen profile was repeated 5 to 10 times at 5 min intervals to confirm the stability of the O2 gradient. An average of approximately 10 profiles was used to calculate OPD and DOU with the PROFILE software (Berg et al., 1998). For these calculations, the boundary conditions included the oxygen concentration in the overlying water and zero flux at the bottom of the oxic zone. The bulk sediment molecular diffusion coefficient (Ds) was estimated using the formula Ds=φ2D0 (Ullman and Aller, 1982), where φ indicates sediment porosity and D0 is the diffusion coefficient in water at the in situ temperature (Li and Gregory, 1974).

2.4 Microphytobenthos quantification and identification

2.4.1 NDVI

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI; Tucker, 1979) is commonly used to measure microphytobenthos (MPB) chlorophyll a in bare sediments at low tide. NDVI utilizes the optical properties of chlorophyll a in the red and near-infrared (NIR) spectral regions (Méléder et al., 2003; van der Wal et al., 2010; Brito et al., 2013; Benyoucef et al., 2014). Specifically, chlorophyll a absorbs strongly in the red part of the spectrum (around 680 nm), yet it reflects light in the NIR region, making these wavelengths effective for detecting chlorophyll a presence and levels. NDVI often serves as a proxy for MPB biomass (Kromkamp et al., 2006; Kazemipour et al., 2012; Benyoucef et al., 2014), since chlorophyll a is a common pigment in MPB organisms, especially diatoms. The NDVI is calculated using the following formula:

R750 represents the reflectance at 750 nm in the NIR, and R673 indicates the red reflectance of chlorophyll at 673 nm (Bargain et al., 2012). Samples for MPB biomass estimation and diatom assemblages were collected from three large sediment cores (12.5 cm diameter). Upon returning to the laboratory, the cores were immersed underwater at the sampling site and left in the dark to settle overnight. Reflectance measurements were taken the next day at low tide, when the MPB biofilms had migrated back to the surface. Cores were kept at very low light levels (10 µmol photons m−2 s−1) to stimulate maximum migration. Conducting all reflectance measurements under these conditions facilitated comparisons across different dates by eliminating the influence of environmental light history. The MPB biomass was estimated from three replicate cores, with three measurements taken at each core to account for spatial variability. All measurements were performed using a JAZ spectroradiometer (OceanOptics), which covers the spectral range of 400–900 nm.

2.4.2 Diatom sampling and species identification

The top 2 mm of the sediment cores, frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C, was subsampled for counting and identifying diatoms. Sediment samples were homogenized using a vortex mixer and transferred to 50 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes, to which 25 mL of fully concentrated Ludox was added, with a density of 1.31 g cm−3. Samples consisting of sandy sediment were ultrasonicated for 10 min to help detach epipsammic diatoms attached to the sand grains. The samples were then centrifuged at 3700 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was poured into a new tube and filled with ultrapure distilled water to rinse away excess Ludox. After centrifuging at 2000 rpm, the supernatant was discarded, and the tubes were refilled with distilled water. This process was repeated five times to ensure complete removal of Ludox residues (see Ribeiro, 2010, for full details). Diatoms were cleaned overnight using a 30 % hydrogen peroxide solution at 60 °C, followed by the addition of hydrochloric acid for 2 h at 60 °C. The cells were then rinsed seven times with ultrapure water, resulting in a final volume of 1.5 mL. A 50 µL subsample was permanently mounted on microscope slides using NaphraxTM. Cell counting, observation, and identification of diatom valves were performed with an Olympus optical microscope. At 1000× magnification, 10 fields were randomly selected until more than 300 individuals were counted. Identification was based on Paulmier (1997), Mertens et al. (2014), and Ribeiro (2010). For analysis, only diatom species with relative abundances above 5 % were identified individually; less abundant taxa were grouped under the category “others”.

2.4.3 Diatom morphological traits and life-forms

Diatom species were classified based on their morphological traits, such as shapes and size classes, and their life-forms. Frustule shapes were identified according to Hillebrand et al. (1999) and from the Atlas of Shapes (https://metadatacatalogue.lifewatch.eu/, last access: January 2026). Biovolumes were obtained from the literature and divided into three size classes: small (< 250 µm3), medium (250–1000 µm3), and large (> 1000 µm3) (Olenina et al., 2006; Ribeiro, 2010; Harrison et al., 2015). Additionally, diatom species were categorized into different life-forms: epipelic, epipsammic, tychopelagic, and pelagic (Méléder et al., 2007; Ribeiro, 2010). To facilitate future analyses by non-diatom taxonomic experts, we also analyzed combined traits, expressed as “size + shape + life-form”, which provide practical functional categories that are more straightforward to apply and interpret than taxonomy alone.

2.5 Foraminifera sampling and species identification

The first centimeter of sediment cores (diameter 8.1 cm) from stations A, B, and C was analyzed for foraminiferal assemblages. Foraminifera densities were standardized and expressed as individuals per 50 cm3 (Schönfeld et al., 2012). Immediately after collection, the top centimeter of the cores was sliced and stained with rose bengal. The sediment slices were then washed and sieved; the fraction larger than 150 µm was examined under a stereomicroscope (Leica S9i, 10× magnification). The foraminifera were wet-picked, and only pink-stained specimens in all chambers except the last one were considered living at the time of sampling. For high-density samples, subsampling was performed with an Otto Microsplitter (Alve and Murray, 2001), allowing the extraction of a sample fraction with at least 300 stained individuals. Foraminifera were placed on micropaleontological slides and identified based on morphological criteria described in the literature (Darling et al., 2016; Richirt et al., 2019; Jorissen et al., 2022).

2.6 Overview of sampling strategies and temporal framework

The monitoring project involves a multidisciplinary team of experts in diatoms, foraminifera, and sediment geochemistry. Sampling was carried out at three stations (A, B, and C), serving as replicates at the La Coupelasse site (Fig. 1). The use of multiple stations as replicates is justified by the strong spatial heterogeneity (patchiness) typical of intertidal mudflats, which can cause significant variability at decametric scales. The initial chosen sampling interval is monthly, corresponding to the estimated response time of benthic foraminifera to integrate environmental variations in accordance with biomonitoring recommendations (Murray and Alve, 2000; Schönfeld et al., 2012). The sampling strategies used between March 2016 and October 2019 are detailed in Table S1 in the Supplement. All variables were measured with replication, except for diatom counting and identification and oxygen profiling. Diatom counting and identification were conducted only at station B to optimize the process, given the limited workforce available at the project's outset. Oxygen profiling was performed exclusively at station C because only one profiling device was available, which prevented measurements at all three stations on the same day. Microphytobenthos sampling was conducted monthly from March 2017 to July 2019. The data were analyzed by season: spring (March, April, May), summer (June, July, August), autumn (September, October, November), and winter (December, January, February).

2.7 Statistical analyses

2.7.1 Selection of environmental variables

First, multicollinearity among environmental variables was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), and highly collinear predictors (VIF > 5) were removed. Spearman's rank correlations were used to evaluate significant monotonic relationships between environmental variables (p<0.05). Since most variables did not follow a normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test, p<0.05), differences between stations and seasons were analyzed with a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc tests. Only variables showing significant seasonal variation were retained for further analyses.

2.7.2 Seasonal patterns in diatom and foraminifera assemblages

To assess the similarity of foraminiferal and diatom assemblages across stations, seasons, or traits, an Analysis of Similarity (ANOSIM) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity was performed, using a significance threshold of p<0.05. The ANOSIM R statistic ranges from 0 to 1, where R≤0.25 indicates weak group separation, indicates moderate separation, and R> 0.50 indicates strong separation. A one-way ANOSIM was used to test the effect of a single independent variable, while a two-way ANOSIM evaluated interactions between stations and seasons for foraminiferal densities. A post hoc Similarity Percentage (SIMPER) analysis was then conducted to identify the species or traits that contribute most to the differences between groups.

2.7.3 Relationship between the environmental variables and the assemblages

To identify the most relevant environmental variables influencing assemblages, a multi-step selection process was used. First, Spearman's correlations (p<0.05) were performed to keep only environmental variables significantly associated with at least one diatom species, diatom trait, or foraminiferal species. Next, a forward selection process (using the ordistep function) based on Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) was applied to find the best set of explanatory variables. The significance of the chosen variables and canonical axes was tested with 999 permutation tests. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA; using the cca function) was conducted to examine relationships between environmental factors and assemblages. All environmental variables were standardized for comparability across datasets. Statistical analyses were carried out using R version 4.5.1 (R Core Team, 2025), the vegan package (Oksanen et al., 2022), and PAST version 5 (Hammer, 2001).

2.7.4 Prediction of the foraminiferal dynamics by diatoms

The distance-based linear model (DistLM) analysis was performed using PRIMER v.6.0.2 software (Clarke and Gorley, 2006). The DistLM model was employed to identify which diatom species could predict temporal changes in foraminiferal species at station B. Foraminiferal species densities were transformed using the square root function, and a Bray–Curtis similarity matrix was generated. Two types of test were conducted with the DistLM model: Marginal and Sequential tests. Marginal tests evaluated the individual contribution of each diatom species to the variation in foraminiferal species densities, considering each diatom species separately when p<0.05. Sequential (or conditional) tests assessed the contribution of each diatom species in the context of those already included in the Marginal test, adding diatoms one by one based on their AIC and p<0.05 values. In this study, diatom species identified by the Sequential test but not by the Marginal test were regarded as occasional species, indicating their less consistent but still significant influence on the temporal variation of foraminiferal species.

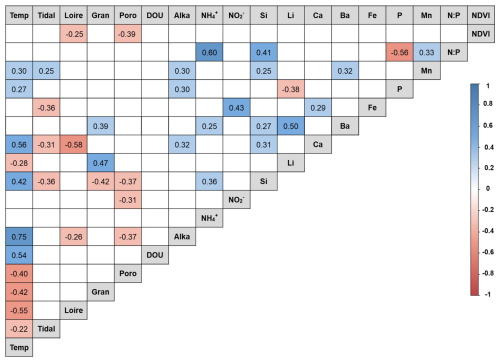

3.1 Selection of environmental variables

A total of 25 environmental variables were measured, including air temperature, tidal coefficient, Loire River discharge, granulometry, porosity, DOU, OPD, salinity, alkalinity, NH, NO, NO, Si, K, Mg, Li, Ca, Ba, Sr, Fe, P, Mn, S, N:P ratio, and NDVI. Nitrates were not detected. Based on VIF analysis, 6 variables (K, Mg, S, Sr, OPD, and salinity) were excluded due to high multicollinearity with other variables, such as salinity and OPD, in relation to the Loire River discharge and porosity. Spearman correlation analysis among the remaining 18 variables revealed several significant associations (Fig. 2). Full details of the environmental dataset are provided in Table S2.

Figure 2Spearman correlation matrix between environmental variables. Positive correlations are represented in blue, and negative correlations are represented in red, according to the color scale. Temp = air temperature; Loire = Loire River discharge; Poro = porosity; DOU = dissolved oxygen uptake; Alka = alkalinity.

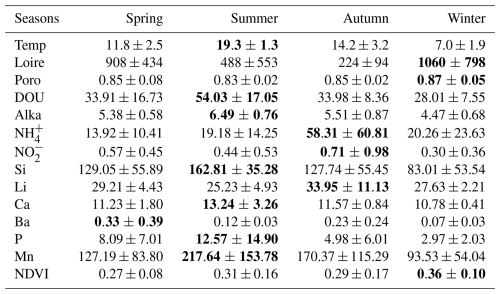

No significant differences were observed between stations (p<0.05). However, 14 variables showed significant seasonal variations (see Table S3). These variables are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1Mean and standard deviation of environmental variables showing significant seasonal variations. The highest values are highlighted in bold. Temp = air temperature (°C); Loire = Loire River discharge (m3 s−1); Poro = porosity; DOU = dissolved oxygen uptake (nmol cm−2 s−1); Alka = alkalinity (mmol L−1); NH = ammonium (µmol L−1); NO = nitrites (µmol L−1); Si = silicium (µmol L−1); Li = lithium (µmol L−1); Ca = calcium (mmol L−1); Ba = barium (µmol L−1); P = phosphorus (µmol L−1); Mn = dissolved manganese (µmol L−1); NDVI = Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. Some variables exhibit standard errors that exceed their mean values, reflecting high underlying variability.

3.2 Analyses of seasonal variations in diatoms

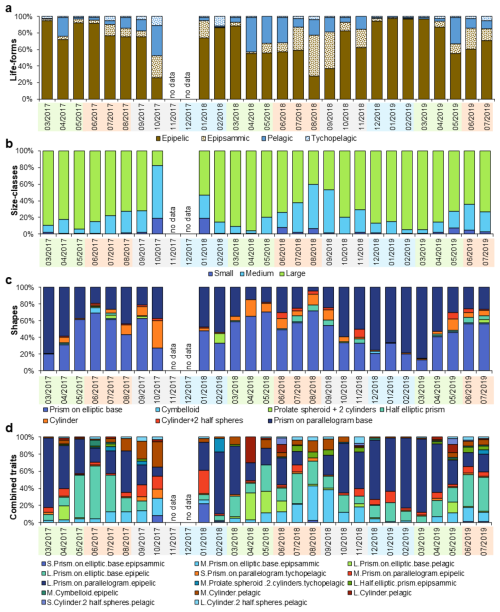

In total, 28 diatom species were identified, and their morphological traits and life-forms are summarized in Table S4. Seven frustule shapes were identified and are illustrated in Fig. 3.

3.2.1 Seasonal patterns in diatoms

A total of 15 diatom species indicated significant seasonal variations (details in Table S4), with the most notable difference observed between summer and winter (R=0.49). Winter assemblages were particularly dominated by Pleurosigma angulatum and Gyrosigma fasciola. Apparent differences also appeared between spring and autumn (R=0.36), with Gyrosigma wansbeckii being most abundant in spring. Meanwhile, Thalassiosira sp., Podosira stelligera, Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii, and Navicula cf. flagellifera were more common in autumn. A moderate change was seen between spring and summer (R=0.27), with summer assemblages marked by increased proportions of Podosira stelligera, Eutonogramma dubium, and Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii.

Trait-based analyses revealed patterns in diatom seasonality that complemented species-level observations (Fig. 4). Epipelic life-forms largely dominated diatom assemblages throughout the year (Fig. 4a). However, seasonal shifts were evident. Epipelic forms peaked in winter, while pelagic forms became more prominent in summer (R=0.32) and again in autumn (R=0.39). In contrast, no seasonal trends were identified for either epipsammic or tychopelagic forms. Concerning diatom size, assemblages were generally dominated by large-sized specimens (Fig. 4b), with a marked dominance in spring. Medium-sized diatoms were also particularly abundant during both spring (R=0.41) and autumn (R=0.51). Small-sized diatoms did not exhibit any discernible seasonal pattern. Regarding morphological shape, seasonal structuring was especially evident. A substantial dissimilarity was observed between winter and summer assemblages (Fig. 4c), with winter communities characterized by prisms with parallelogram bases. In contrast, summer communities showed a dominance of prisms with elliptic bases and cylindrical forms (R=0.80). Autumn was distinguished by the prevalence of cylindrical forms, including cylinders with half-spheres (R=0.38).

When examining combined trait categories, covering size, shape, and life-form, distinct seasonal patterns emerged (Fig. 4d). Winter assemblages were dominated by diatoms classified as “large + prism on parallelogram base + epipelic.” In contrast, summer assemblages showed a higher presence of “large + half-prism on elliptic base + epipsammic” and “large + cylinder with half-spheres + pelagic” combinations (R=0.70), indicating a shift in both functional and morphological composition across seasons.

3.2.2 Correlations between diatoms and environmental variables

A total of 10 environmental variables were strongly associated with both diatom species and traits, confirming the influence of abiotic factors on assemblage composition (see Fig. 5 and detailed outputs in Table S5). Air temperature was negatively correlated with Gyrosigma fasciola but positively correlated with several species, including Entomoneis paludosa, Eutonogramma dubium, Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii, Thalassiosira sp., and Podosira stelligera. Discharge of the Loire River was positively related to Gyrosigma wansbeckii and negatively associated with most of the previous taxa (Fig. 5). Alkalinity demonstrated a strong negative correlation with Pleurosigma angulatum and positive associations with Eutonogramma dubium, Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii, Cymatosira belgica, Thalassiosira sp., and Podosira stelligera. Additional significant correlations were found for porosity (Plagiotropis vanheurckii), (Gyrosigma wansbeckii), Si (Gyrosigma fasciola and Navicula spartinetensis), NH (Navicula spartinetensis), Ca (Eutonogramma dubium and Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii), and P (Entomoneis paludosa). Some species, such as Pleurosigma aestuarii, Nitzschia cf. distans, Navicula cf. flagellifera, and Skeletonema sp., showed no detectable relationships.

Figure 5Sort summary of the significant Spearman correlations between environmental variables and diatom species and traits. Positive correlations are represented in blue, and negative correlations are represented in red, according to the color scale. Temp = air temperature; Loire = Loire River discharge; Poro = porosity; Alka = alkalinity.

3.3 Analyses of seasonal and spatial variations in foraminifera

The dominant foraminiferal species identified were Ammonia confertitesta (Zheng, 1978; phylotype T6 in Hayward et al., 2021), Haynesina germanica (Ehrenberg, 1840), Elphidium oceanense (d'Orbigny in Fornasini, 1904), and Elphidium selseyense (Heron-Allen and Earland, 1911) (Fig. 6). The total density of individuals varied considerably over the ∼ 3.5-year time series, with a mean of 638 ± 460 individuals per 50 cm3. Densities ranged from a minimum of 29 individuals per 50 cm3 recorded in spring 2019 at station B to a peak of 3542 individuals per 50 cm3 observed in summer 2018 at station C. The foraminiferal species dataset is detailed in Table S6.

No spatial differences were detected for the average densities of the four foraminiferal species (p > 0.05), but notable differences in densities were observed between seasons (p<0.05). On the other hand, spatiotemporal structuring effects were identified with some station–season interactions.

Figure 6Scanning electron microscope images of the dominant foraminifera species (a) Ammonia confertitesta, (b) Haynesina germanica, (c) Elphidium oceanense, and (d) Elphidium selseyense. The scale bar indicates 100 µm.

3.3.1 Seasonal and spatial patterns in foraminifera

Ammonia confertitesta was the dominant species. Its population exhibited a biannual cycle, with density peaks typically occurring in spring and autumn, except in 2019 (Fig. 7). Significant station–season interactions were observed, particularly in autumn, indicating increased spatial variability (Table S7). Densities of A. confertitesta frequently exceeded 1000 individuals per 50 cm3 during spring and late summer/autumn, with the maximum recorded density of 1507 individuals per 50 cm3 in September 2017 at station C (Fig. 7).

While A. confertitesta shared a similar distribution pattern with Haynesina germanica (Spearman ρ=0.68), only a weak station–season interaction was detected for H. germanica, specifically between spring and autumn at station B (R=0.18). Haynesina germanica densities peaked predominantly in autumn, reaching a maximum of 1099 individuals per 50 cm3 in late August 2018 at station B (Fig. 7).

Similarly, A. confertitesta showed a moderate correlation in distribution with Elphidium oceanense (Spearman ρ=0.56), while H. germanica and E. oceanense were more strongly correlated (Spearman ρ=0.65). Elphidium oceanense exhibited a marked seasonal shift, with significant differences between spring and autumn (R=0.61), indicating a time lag in population dynamics relative to the two previous dominant species. Multiple station–season interactions were identified, especially in autumn, coinciding with increased spatial variability and elevated densities of E. oceanense. Peak densities were recorded in summer and autumn, with a maximum of 1367 individuals per 50 cm3 in late August 2018 at station C (Fig. 7).

Elphidium selseyense displayed consistently lower densities than the other species. The most notable seasonal differences occurred between summer and winter (R = 0.19) and between summer and autumn (R = 0.18). No significant station–season interaction was found (p > 0.05). Density peaks were observed in late spring and summer, with the highest density of 463 individuals per 50 cm3 recorded in April 2016 at station C (Fig. 7).

Figure 7Foraminiferal densities (individuals per 50 cm3) of the four dominant species at the three stations A, B, and C in La Coupelasse. No data labels indicate that no sampling occurred for a month. Colors indicate seasons with spring (green), summer (orange), autumn (gray), and winter (blue). Pay attention to the change in scale for E. selseyense.

3.3.2 Correlations between foraminifera and environmental variables

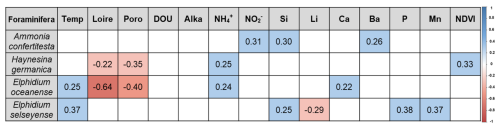

A total of 12 environmental variables exhibited significant correlations with at least one foraminiferal species (Fig. 8). Interestingly, Haynesina germanica was the only species that correlated with NDVI. Both H. germanica and E. oceanense showed negative correlations with Loire River discharge and porosity and positive correlations with NH. Ammonia confertitesta also correlated with another nutrient, NO, and with Si content, like E. selseyense. Both Elphidium species exhibited positive correlations with air temperature; however, E. selseyense was the only species to show positive correlations with P and Mn concentrations.

Figure 8Significant Spearman correlations between environmental variables and foraminiferal species. Positive correlations are represented in blue, and negative correlations are represented in red, according to the color scale. Temp = air temperature; Loire = Loire River discharge; Poro = porosity; DOU = dissolved oxygen uptake; Alka = alkalinity.

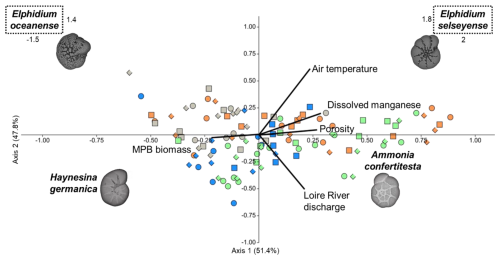

Following the forward selection, the placement of foraminiferal species along the CCA axes revealed distinct ecological niches influenced by five environmental variables (Fig. 9). The first and second axes explained 51.4 % and 47.8 % of the constrained variance, respectively, totaling 99.2 % (p0.001, n=999). Ammonia confertitesta (AC) was positively correlated with Axis 1 and negatively affected by the discharge of the Loire River, which shaped Axis 2. Haynesina germanica (HG) was negatively positioned along both axes, showing negative correlations with Loire River discharge and porosity and a positive correlation with NDVI. Elphidium oceanense (EO) exhibited a negative position on Axis 1 and a positive position on Axis 2, with a positive correlation to air temperature and a negative correlation to Loire River discharge and porosity. In contrast, E. selseyense (ES) was positively positioned along both axes, correlating positively with air temperature and dissolved manganese (Mn).

Figure 9Canonical correspondence analysis after forward selection based on air temperature, dissolved manganese, porosity, Loire River discharge, and NDVI as constrained variables (black lines), with benthic foraminifera densities as secondary variables. Pay attention to the scale concerning both Elphidium species. Colors represent seasons: spring (green), summer (orange), autumn (gray), and winter (blue). Shapes indicate stations: station A (dot), station B (square), and station C (diamond).

3.4 Linking key diatom species to seasonal foraminiferal species dynamics

Among the 28 diatom species identified at La Coupelasse, 16 species exhibited correlations with the seasonal variability of foraminiferal species at station B (Fig. 10). Six diatom species, mainly epipelic form, were associated with A. confertitesta, including diatoms of various sizes and shapes (see details in Fig. 10). Two diatom species, Pleurosigma aestuarii and Gyrosigma fasciola, were linked to both A. confertitesta and H. germanica. Six diatom species correlated with H. germanica dynamics, all large and epipelic (Fig. 10). For E. oceanense, 10 diatom species were associated, showing the most remarkable diversity in shape, size, and life-form (Fig. 10). Among these, Plagiotropis vanheurckii and Navicula cf. flagellifera were also linked to H. germanica. Additionally, Thalassiosira sp. and Navicula spartinetensis overlapped with A. confertitesta. No diatom species were shared among these three foraminiferal species (white area, Fig. 10). The seasonal variability of E. selseyense appeared to be influenced by a single, occasional diatom species, Navicula abscondita, characterized by its large size and epipelic form (Fig. 10). The distLM model dataset is available in Table S8.

Figure 10Selected diatom species that explain the most foraminiferal seasonal dynamics in La Coupelasse mudflat. The diatom species are classified based on their shape, size, and life-form. Underlined names indicate occasional species. Diatoms within the blue-framed area correspond to Ammonia confertitesta; those in the green-framed area correspond to Haynesina germanica. Diatoms shown in the gray-framed area are associated with Elphidium oceanense, while those in the yellow-framed area are linked to Elphidium selseyense.

4.1 Seasonal environmental context in La Coupelasse mudflat

Understanding the seasonal hydrodynamic and geochemical conditions at La Coupelasse mudflat is essential for interpreting changes in diatoms and foraminiferal assemblages. The mudflat undergoes a shift between a winter–spring period of disturbance and a summer–autumn phase of stabilization.

The influence of the Loire estuary on the Bay of Bourgneuf remains debated, particularly regarding freshwater inputs and associated chemical fluxes (Barillé-Boyer et al., 1997). Nevertheless, the seasonal hydrodynamics of the Bay of Bourgneuf are characterized by intense sediment resuspension during winter and early spring, driven by river flooding, strong currents, tidal dynamics, precipitation, and wind events (Haure and Baud, 1995; Barillé-Boyer et al., 1997; Méléder et al., 2005, 2007). In contrast, late spring and summer are marked by more stable conditions with reduced freshwater inputs. These resuspension events can generate flood deposits on mudflats; however, the thickness of such deposits at La Coupelasse remains undetermined. In comparable environments along the French Atlantic coast, flood deposits typically range from 5 to 10 cm (Deloffre et al., 2006; Goubert et al., 2010; Guilhermic et al., 2023). While granulometry, particularly particles < 63 µm, has traditionally served as a proxy for hydrodynamic energy (Méléder et al., 2007; Jesus et al., 2009), grain size at La Coupelasse remained relatively constant. Instead, sediment porosity emerged as a more responsive indicator. Increased porosity during winter may suggest the formation of flood deposits or sediment reworking, indicating sediment instability (Fig. 2). Conversely, compaction during summer, driven by warmer temperatures and lower hydrodynamic conditions, leads to reduced porosity, indicating sedimentary stability. This seasonal pattern parallels findings from Les Brillantes (Loire estuary), where flood deposits exhibited high porosity and were enriched in labile organic matter (OM) and reactive oxides such as Fe and Mn (Thibault de Chanvalon et al., 2016).

Transition metals, such as Fe and Mn, are sensitive redox indicators that reflect seasonal sedimentary processes. Although Fe showed limited variability and lacked correlation with Mn, a pronounced increase in dissolved Mn post-winter suggests a transient diagenetic state (Deflandre et al., 2002; Thibault de Chanvalon et al., 2016). During this phase, oxygen and nitrate are sequentially consumed during OM degradation (Aller, 2004), followed by Mn and Fe oxide reduction (Hyacinthe et al., 2001; Anschutz et al., 2005). This results in elevated pools of reduced metals, particularly in spring and summer, as reflected by higher dissolved Mn concentrations and concurrent increases in alkalinity and DOU (Table 1). These findings suggest that winter oxide deposition is succeeded by intensified remineralization in warmer months, jointly regulating the seasonal dynamics of Mn and Fe. Ca and Si also exhibit seasonal variability and serve as tracers of hydrological inputs. In the nearby Vie estuary, Ca is associated with oceanic influence during summer, while Si is linked to freshwater input in winter (Debenay et al., 2006). This pattern is consistent with La Coupelasse, where Ca concentrations peak in summer, corresponding to elevated temperatures and diminished Loire River discharge (Table 1). Si, however, exhibited unexpectedly high concentrations in summer (Table 1). While increased freshwater input typically elevates Si in winter, summer peaks may reflect evaporation or reduced uptake by MPB, notably diatoms. Lower Si in winter might be explained by enhanced MPB assimilation, as suggested by higher NDVI values during that season (Table 1). Other elements, such as Ba and Li, displayed notable but complex seasonal trends (Table 1). Ba is a known proxy for marine productivity (Carter et al., 2020), and Li is indicative of continental weathering within the Loire basin (Millot and Négrel, 2021). Given the multiple biogeochemical pathways governing Ba and Li, site-specific studies are needed to unravel their seasonal behavior in the Bay of Bourgneuf.

Among nutrients, P, which can be limiting in estuarine systems (Thibault de Chanvalon et al., 2016), showed no correlation with NDVI in the study area (Fig. 2). Phosphorus cycling occurs primarily at depth and is released during OM oxidation and reductive dissolution of Fe oxides (Thibault de Chanvalon et al., 2015, 2016). This process likely explains elevated P concentrations in summer (Table 1). However, P remains scarce at the sediment surface due to adsorption onto Fe oxides and assimilation by MPB. The lack of significant bioturbation at La Coupelasse limits the upward transport of P, emphasizing the need for investigations into deeper sediment layers. NH concentrations exceeded those of P and showed marked variability, particularly in autumn (Table 1), exceeding those reported in other estuaries such as the Tagus (Jesus et al., 2009). A strong positive correlation was observed between NH and the N:P ratio, though NDVI remained uncorrelated (Fig. 2). As a preferred nitrogen source for MPB (Welker et al., 2002), NH likely originates from anoxic sediment layers and diffuses upward (Metzger et al., 2019). Nitrite concentrations were low but seasonally variable (Table 1), indicative of ongoing nitrification, while nitrate was undetectable, likely due to rapid denitrification or MPB uptake.

A complex interplay emerges between NDVI values and sediment properties. Although there is a negative trend between NDVI and porosity and Loire River discharge (Fig. 2), higher NDVI values were observed in winter (Table 1). Previous studies have demonstrated that compact, stable muds can promote MPB growth by minimizing physical disturbance and enhancing biofilm development through extracellular polymeric substances (Decho, 2000; Blanchard et al., 2006; Jesus et al., 2009; Mariotti and Fagherazzi, 2012). This underscores the nuanced and non-linear relationships between hydrodynamic stability, nutrient fluxes, and primary productivity at La Coupelasse.

In summary, La Coupelasse mudflat undergoes a cyclical sequence: winter disturbances promote oxide deposition and sediment reworking, while summer stabilization enhances compaction, remineralization, and the release of nutrients. These processes jointly regulate the availability of redox-sensitive metals, nutrients, and MPB activity, providing the seasonal environmental framework necessary to interpret the dynamics of diatom and foraminiferal assemblages.

4.2 Seasonal dynamics of diatoms and foraminifera

4.2.1 Seasonal dynamics of diatoms

This work focused on diatoms, which dominate the MPB community and represent a key food source for the benthic foraminifera inhabiting this area (Méléder et al., 2007; Schweizer et al., 2022). Although the sampling interval applied in this study did not capture all MPB bloom events, some of which may last less than a month, the diatom assemblages observed at La Coupelasse (Table S4) were consistent with previous records from the bay and resembled those in other European mesotidal and macrotidal estuaries (e.g., Ribeiro et al., 2003; Sahan et al., 2007; Méléder et al., 2007; Chronopoulou et al., 2019; Schweizer et al., 2022). Although species composition remains a useful ecological indicator, trait-based approaches provide complementary insights and are easier to identify for non-specialists in diatoms. Previous research already indicates that morphological and functional traits at the individual level serve as better predictors of phytoplankton dynamics than species richness alone (Fontana et al., 2018). In this study, not all diatom species chosen to predict the temporal dynamics of foraminifera correlate with environmental data, prompting an additional focus on individual traits and combined traits as alternatives.

Life-form traits revealed marked seasonal patterns (Fig. 4a). Epipelic diatoms dominated in winter, aligning with turbulent conditions and cooler temperatures typical of temperate muddy intertidal zones (Méléder et al., 2007; Jesus et al., 2009; Ribeiro et al., 2021). Pelagic diatoms became more prevalent in summer and autumn, as they may settle on the sediment surface after being transported by currents and tides (Padisák et al., 2003), suggesting a weaker hydrodynamic regime and possible increased marine influence. Epipsammic and tychopelagic forms contributed less to seasonal dissimilarity. The scarcity of epipsammic taxa compared to epipelic ones, typical of sandier environments like the northern Bay of Bourgneuf (Méléder et al., 2007), suggests limited sandy input at La Coupelasse. Their occurrence correlated with reduced sediment porosity, possibly indicating sporadic sand transport. Tychopelagic diatoms were sporadically detected, likely underestimated due to sampling methods favoring the motile epipelic fraction (Ribeiro et al., 2003, 2021). These diatoms, which shift between pelagic and benthic phases, exploit estuarine turbidity and tidal resuspension for dispersal (Ribeiro et al., 2021). A correlation with higher alkalinity suggests an increased presence of tychopelagic organisms during summer, although further investigation is needed. The size class distribution also followed seasonal trends. Large diatoms peaked in spring, while medium-sized forms dominated during summer and autumn (Fig. 4b), possibly responding to a seasonal cycle characterized by lower hydrodynamic stress and higher air temperatures. Small diatoms were underrepresented, limiting further interpretation. Nonetheless, shape-based traits also highlighted seasonal structuring (Fig. 4c): winter assemblages featured prisms on a parallelogram base (e.g., Gyrosigma wansbeckii). At the same time, summer communities favored prisms on an elliptic base (e.g., Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii, Entomoneis paludosa) and cylinders with half-spheres (e.g., Podosira stelligera). Regarding the combined traits, the winter combination “large + prism on parallelogram base + epipelic” was associated with high Loire River discharge and low air temperatures, corresponding to the dominance of Pleurosigma and Gyrosigma, especially G. wansbeckii. The prevalence of elongated, high surface area forms may suggest an adaptive advantage for light and nutrient uptake (Karp-Boss and Boss, 2016; Laraib et al., 2023). In contrast, summer assemblages were marked by “medium + prism on elliptic base + epipsammic” (Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii) and “large + cylinders with half-spheres + pelagic” (Podosira stelligera), consistent with weaker hydrodynamics.

In summary, the analysis of individual and combined traits reveals distinct seasonal strategies in diatom assemblages, with (1) winter communities reflecting adaptations to high Loire River discharge and turbulent conditions and (2) summer communities associated with weaker hydrodynamics and a more marine influence in the bay. This highlights the importance of trait-based approaches as complementary indicators to species-level analyses.

4.2.2 Seasonal dynamics of foraminifera

Low species richness in adult foraminifera (> 150 µm) was observed at La Coupelasse, a typical characteristic of temperate Atlantic intertidal mudflats (Debenay et al., 2006; Mojtahid et al., 2016; Fouet et al., 2022; Pavard et al., 2023; Daviray et al., 2024; Daché et al., 2024). Few studies in the Bay of Bourgneuf have explored foraminiferal ecology, with most of them focusing on spatial gradients (Debenay, 1978; Debenay and Guillou, 2002). The La Coupelasse site has primarily been used for foraminiferal experimental research (e.g., Morvan et al., 2004; Jauffrais et al., 2016; Jesus et al., 2022; Guilhermic et al., 2023).

The patchiness observed in foraminiferal density, also noted in this study, is a well-documented challenge in intertidal environments (e.g., Bouchet et al., 2007; Thibault de Chanvalon et al., 2015, 2022; Buzas et al., 2015; Fouet et al., 2022). The lack of significant spatial differences between the three stations may be due to their situation within the same sector of the bay and may not represent a land–sea gradient, as typically defined in estuarine studies (Debenay et al., 2000). However, some season–station interaction effects were observed for Ammonia confertitesta and Elphidium oceanense, suggesting that seasons, particularly autumn when densities were higher, affect the spatial distribution at the decametric scale. While Haynesina germanica densities exhibited station-specific seasonal variability, with higher densities at Station B, the most distant from the path (Figs. 1 and 7), the patchy distribution of foraminifera can complicate the interpretation of natural population dynamics, especially for bioindicator species (Schönfeld et al., 2012). Similar issues may also apply to MPB (Guarini et al., 1997; Seuront and Spilmont, 2002; Jesus et al., 2006). Therefore, this study only used foraminiferal data from station B for comparison with diatom assemblages, highlighting that a more integrated MPB–foraminifera station–season analysis should be investigated in future research.

Despite spatial variability, the studied foraminiferal species showed clear seasonal ecological preferences (Fig. 9). Ammonia confertitesta, H. germanica, and E. oceanense displayed similar temporal patterns. However, interannual shifts in their reproductive peaks were observed (Fig. 7). For example, A. confertitesta and H. germanica reproduced in spring and late autumn 2016, early autumn 2017, and late summer 2018. These shifts likely reflect environmental variability, including hydrodynamic conditions. Notably, A. confertitesta and H. germanica alternated in dominance across seasons, indicating niche partitioning through seasonal shifts in dominance. Individual environmental variables significantly linked to A. confertitesta densities (Fig. 8) were not selected by the CCA (Fig. 9), making interpretation more difficult. This could be due to the high ecological tolerance of the species. Additionally, the CCA suggests that A. confertitesta preferred cooler, more hydrodynamic environments (Fig. 9), which aligns with its classification as an euryhaline and opportunistic species (Richirt et al., 2019; Bird et al., 2020; Fouet et al., 2022; Pavard et al., 2023).

Haynesina germanica, another euryhaline species, usually inhabits shallow zones and salt marshes along estuarine gradients (Debenay and Guillou, 2002; Darling et al., 2016; Mojtahid et al., 2016; Pavard et al., 2023). In this study, its densities showed a positive correlation with NDVI and NH and a negative one with sediment porosity and Loire River discharge (Fig. 8). These relationships align with the CCA (Fig. 9), indicating a preference for low hydrodynamic, higher-productivity environments, which supports its known trophic strategies, such as kleptoplasty (Lopez, 1979; Jauffrais et al., 2016). These field-based results support experimental findings from Guilhermic et al. (2023), who showed that H. germanica is vulnerable to sediment disturbance, a condition incompatible with its photosynthetic activity, which requires stable access to light. This is consistent with its lower disturbance tolerance compared to A. confertitesta. Seasonal niche differentiation between these species may also reduce trophic competition (Cesbron et al., 2017). While the seasonal photosynthetic performance of H. germanica remains poorly understood, its presence year-round suggests that kleptoplasts serve as an additional nutrient source, supporting a mixotrophic strategy during periods of low productivity (Cesbron et al., 2017). Additionally, it may benefit from higher light levels through photoregulatory mechanisms (Jauffrais et al., 2017; Jesus et al., 2022).

Elphidium oceanense was less common than A. confertitesta and H. germanica, a pattern consistent with earlier estuarine research (Debenay et al., 2006; Darling et al., 2016; Fouet et al., 2022; Pavard et al., 2023). Reproductive activity at La Coupelasse was observed in late summer and early autumn (Fig. 7). Elphidium oceanense exhibited the strongest environmental correlations, including those shared with H. germanica, and positive links to Ca and air temperature (Fig. 8). These patterns were confirmed by the CCA, which indicated a preference for warm, low-energy environments and a greater influence of marine conditions in the bay (Fig. 9).

In contrast, E. selseyense was uncommon and showed one small reproductive peak observed in spring and summer (Fig. 7), suggesting that local environmental conditions may be suboptimal for this species. Although E. selseyense is widely distributed along the European Atlantic coast from Norway to the Bay of Biscay, its limited presence in the Bay of Bourgneuf contradicts its supposed tolerance of colder waters compared to E. oceanense (Darling et al., 2016; Fouet et al., 2022). The occurrence of E. selseyense probably reflected increased oceanic influence during the summer, aligning with minimal freshwater input in the Bay of Bourgneuf. This idea was supported by correlations with summer environmental data (Fig. 8) and CCA results (Fig. 9). Summer sediments were enriched in phosphorus and potentially in dissolved OM, which could be beneficial for the food sources of E. selseyense.

Although efforts were made to connect MPB to foraminiferal ecology, NDVI proved to be a limited predictor of foraminiferal seasonal changes, except for H. germanica (Fig. 8). This suggests that combining species-level and trait-based analyses of diatoms may provide deeper insights into foraminiferal trophic dynamics, as discussed in the next subsection.

4.3 Linking diatom species and traits to seasonal patterns in foraminiferal species

The predictive model identified 16 diatom species as potential predictors of the temporal dynamics of foraminiferal species (Fig. 10). This model was especially suitable for Haynesina germanica and both Elphidium species, which are known to feed mainly on diatoms (Pillet et al., 2011; Chronopoulou et al., 2019; Schweizer et al., 2022). Half of these diatom species showed clear seasonal patterns: Thalassiosira sp., Gyrosigma fasciola, Navicula cf. flagellifera, Eutonogramma dubium, Gyrosigma wansbeckii, Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii, and Podosira stelligera (Fig. 10). The other species did not display seasonality and required the use of morphological and life-form traits to understand their role in foraminiferal seasonal patterns.

Ammonia confertitesta, considered omnivorous with a predatory tendency toward small metazoans, also feeds on phototrophic organisms, including diatoms (Dupuy et al., 2010; Chronopoulou et al., 2019; Schweizer et al., 2022). While interpreting the selected diatom predictors for A. confertitesta, caution should be exercised, as evidence from the Bay of Bourgneuf suggests that this species may rely more heavily on diatoms when they are abundant (Schweizer et al., 2022). The diatoms associated with A. confertitesta were diverse in shape and size, with a predominance of elongated, cylindrical, and epipelic or pelagic forms (Fig. 10), such as Gyrosigma and Thalassiosira, which were also found in microbiome analyses from the Bay of Bourgneuf (Schweizer et al., 2022). Other selected genera, such as Pleurosigma, Cymatosira, and Navicula, although not directly identified in microbiome studies at this site, may reflect the patchiness of diatoms across mudflats or variation in microhabitats. Additional diatom species, such as Petrodictyon sp. and Actinocyclus sp., have been detected in the Ammonia microbiome from other mudflats, including those found in the Dutch Wadden Sea (Chronopoulou et al., 2019). However, all these diatoms exhibit morphological traits that are suited to the diet of A. confertitesta. Most of the selected diatom species did not show pronounced seasonality; therefore, understanding seasonal dynamics requires considering the combined traits of these species. Ammonia confertitesta may experience seasonal changes in its diatom food sources, shifting from “large + prism on parallelogram base + epipelic” diatoms in winter and spring to “large + prism on elliptical base + epipelic” and “medium + cylindrical + pelagic” diatoms during summer and autumn.

Haynesina germanica, in contrast, exhibited a more selective feeding behavior, preferring large, elongated epipelic diatoms with prism on elliptic or prism on parallelogram frustule shapes (Fig. 10). This selectivity is supported by microbiome studies from the Bay of Bourgneuf (Schweizer et al., 2022) and earlier research by Pillet et al. (2011), which identified Gyrosigma, Pleurosigma, and Navicula as primary food sources. Although some diatoms, such as Nitzschia cf. distans, Entomoneis paludosa, and Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii, were not previously detected in microbiomes, they share morphological and life-form traits with confirmed dietary items and may still be important. This idea is also confirmed by other pennate diatoms, like Petrodictyon sp., Donkinia sp., and Cylindrotheca sp., as well as other Bacillariophyceae found in another mudflat, the Dutch Wadden Sea; however, H. germanica is found living deeper in the sediment there (Chronopoulou et al., 2019). Similar to A. confertitesta, H. germanica might also undergo a seasonal shift, focusing on diatom shapes that were “large + prism on parallelogram base + epipelic” in winter and spring and “large + prism on elliptic base + epipelic” in summer and autumn. Diatom morphology could influence the efficiency of kleptoplasty in H. germanica, as this species cracks diatom frustules externally and retains chloroplasts (Austin et al., 2005; Jauffrais et al., 2016; Jesus et al., 2022). Seasonal changes in dominant diatom shapes (Fig. 4c) might affect kleptoplast performance, especially if linked to pigment content and frustule morphology (Jauffrais et al., 2017). This hypothesis still needs further investigation.

Elphidium oceanense exhibited the broadest trophic range among the species studied, consuming diatoms across a broad spectrum of sizes, shapes, and life-forms (Fig. 10), consistent with microbiome results from the Bay of Bourgneuf (Schweizer et al., 2022). Diatom species like Navicula, Thalassiosira, and Entomoneis were selected as predictors and are known to be dietary components. Others, such as Odontella and Nitzschia, although present in microbiome data, did not show temporal correlation in this study, possibly due to patchiness. In fact, information on E. oceanense ecology in the literature is quite limited, as this species was often confused with others in the E. excavatum morphospecies group (Schweizer et al., 2022). The preference of E. oceanense for pelagic diatoms likely reflects its tendency to occur in more oceanic conditions during warmer, less hydrodynamic periods (Debenay et al., 2000; Mojtahid et al., 2016; Darling et al., 2016; Fouet et al., 2022). Most of the selected species exhibited clear seasonal patterns, and the combined traits provided comparable and valuable insights into their ecology. The identified species were mainly associated with summer and autumn, exhibiting traits such as “large + prism on elliptic base + epipelic”, “large + cylinder with half-spheres + pelagic”, and “medium + cylindrical + pelagic” forms. Species like Eutonogramma dubium (epipsammic) and Plagiogrammopsis vanheurckii (tychopelagic) were also included in this seasonal group. In contrast, Gyrosigma wansbeckii, characterized as “large + prism on parallelogram base + epipelic”, indicates an occurrence during winter and spring. This pattern also aligned with the seasonal dynamics of E. oceanense.

The food source of Elphidium selseyense remained enigmatic. No diatom species clearly explained its seasonal dynamics, except Navicula abscondita, associated with late spring and summer periods, corresponding to E. selseyense peaks (Fig. 7). Previous microbiome data from the Dutch Wadden Sea (Chronopoulou et al., 2019) revealed a different set of dietary diatoms, Climacosphenia, Rhaphoneis, and Thalassiosira, suggesting either regional variation or broader trophic flexibility. In the Bay of Bourgneuf, green algae (e.g., Euglenophyceae) are more abundant in summer (Méléder et al., 2007), raising the possibility that E. selseyense might rely more heavily on other food sources, such as non-diatom microalgae or dissolved OM. Additional microbiome studies are needed to clarify its trophic ecology.

The species-based predictive model participated in explaining the temporal dynamics of foraminifera in La Coupelasse mudflat. However, interpreting diatom species based on their individual traits and, importantly, their combined traits helped us understand the dietary shifts of the foraminiferal species within seasonal contexts. These findings emphasize the importance of considering combined traits to interpret diatom–foraminifera trophic interactions.

This study has showed that coupling diatom–foraminifera assemblages provides valuable insight into an overlooked trophic level within the La Coupelasse mudflat (Bay of Bourgneuf), a pilot site for long-term biomonitoring along the French Atlantic coast. The seasonal hydrodynamic and geochemical cycles at La Coupelasse mudflat structure benthic communities through alternating phases of disturbance and stabilization: winter–spring seasons enhance oxide deposition and sediment reworking, whereas summer–autumn seasons promote sediment compaction, remineralization, and nutrient release. These processes regulate redox-sensitive metal availability, nutrient cycling, and MPB biomass, shaping the environmental framework that drives diatom and foraminiferal responses. The NDVI appears to be a limited predictor of foraminiferal species dynamics, while diatom assemblages indicate pronounced seasonal shifts. Morphological (frustule size and shape) and life-form traits, particularly when considered combined (“size + shape + life-form”), are as informative as taxonomic composition for capturing ecological responses to environmental variability. The diatom species linked to Ammonia confertitesta are morphologically diverse, encompassing a wide range of sizes and shapes, with a predominance of elongated and cylindrical shapes, and epipelic or pelagic life-forms. Ammonia confertitesta shows seasonal variations, with two annual density peaks in spring and autumn corresponding to shifts in its diatom food sources, from “large + prism on parallelogram base + epipelic” diatoms in winter and spring to “large + prism on elliptical base + epipelic” and “medium + cylindrical + pelagic” diatoms during summer and autumn. Haynesina germanica, although displaying two annual density peaks in spring and autumn synchronous with those of A. confertitesta, exhibits a more selective feeding pattern. Haynesina germanica prefers to consume large, elongated epipelic diatoms, with a seasonal change in shape, characterized as “large + prism on a parallelogram base + epipelic” during winter and spring and “large + prism on an elliptical base + epipelic” during summer and autumn. Elphidium oceanense shows the broadest trophic range, consuming diatoms across a wide range of sizes, shapes, and life-forms. The preference of E. oceanense for pelagic diatoms likely reflects its occurrence under more oceanic, low-energy conditions typical of warmer periods in the bay. The diatom species identified are mainly associated with summer and autumn, corresponding to the annual density peak of E. oceanense in early autumn, exhibiting traits such as “large + prism on elliptic base + epipelic”, “large + cylinder with half-spheres + pelagic”, and “medium + cylindrical + pelagic”. In contrast, the food source of Elphidium selseyense involving diatoms remains uncertain, although its late spring density peak may be associated with one “large + prism on elliptic base + epipelic” diatom. These results emphasize the importance of functional diversity in shaping diatom–foraminifera trophic interactions. Notably, the findings suggest that focusing on diatom traits, rather than species or MPB biomass, provides an encouraging method for understanding foraminiferal dynamics. Future studies should explore larger spatial and temporal scales to strengthen this work. Ultimately, by linking trait-based primary producer activities to consumer behavior, this research enhances predictions of ecosystem responses to seasonal change and offers insights for conserving and sustainably managing biodiversity and productivity in intertidal mudflats.

All datasets discussed in this work are available in Tables S1–S8 in the Supplement.

The samples are stored at the UMR 6112 LPG, Angers University, CNRS, France, and Nantes University, Mer Molécules Santé, EA 2160, France.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-45-51-2026-supplement.

CC: writing (original draft), investigation, formal analysis, data curation. EG: writing (review and editing), supervision, investigation. EM: writing (review and editing), supervision, investigation, data curation. EH: writing (review and editing), data curation. BJ: writing (review and editing), supervision, data curation. MS: writing (review and editing), data curation. AP: writing (review and editing), data curation. TJ: writing (review and editing), data curation. EB: sampling, data curation. AM: writing (review and editing), supervision, data curation.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Advances and challenges in modern and benthic foraminifera research: a special issue dedicated to Professor John Murray”. It is not associated with a conference.

The authors thank Vona Méléder and Julia Courtial for their feedback on the data analysis. The authors are also grateful for constructive criticism and feedback from the two reviewers and the editors.

This research was funded by the Region Pays de la Loire through the following projects: COSELMAR, FRESCO, and OSUNA-RS2E. The French national program EC2CO-LEFE also financed this study through the project Manga-2D. Core data from the OSUNA project MUDSURV also support this research.

This paper was edited by Francesca Sangiorgi and Babette Hoogakker and reviewed by Giacomo Galli and one anonymous referee.

Admiraal, W., Peletier, H., and Brouwer, T.: The Seasonal Succession Patterns of Diatom Species on an Intertidal Mudflat: An Experimental Analysis, Oikos, 42, 30–40, https://doi.org/10.2307/3544606, 1984.

Alexander, S. P. and Banner, F. T.: The functional relationship between skeleton and cytoplasm in Haynesina germanica (Ehrenberg), Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 14, 159–170, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.14.3.159, 1984.

Aller, R. C.: Conceptual models of early diagenetic processes: The muddy seafloor as an unsteady, batch reactor, Journal of Marine Research 62, https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/journal_of_marine_research/64 (last access: January 2026), 2004.

Alve, E. and Murray, J.: Temporal variability in vertical distributions of live (stained) intertidal foraminifera, Southern England, The Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 31, 12–24, https://doi.org/10.2113/0310012, 2001.

Anschutz, P., Dedieu, K., Desmazes, F., and Chaillou, G.: Speciation, oxidation state, and reactivity of particulate manganese in marine sediments – ScienceDirect, Chemical Geology, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.01.008, 2005.

Austin, H. A., Austin, W. E. N., and Paterson, D. M.: Extracellular cracking and content removal of the benthic diatom Pleurosigma angulatum (Quekett) by the benthic foraminifera Haynesina germanica (Ehrenberg), Marine Micropaleontology, 57, 68–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2005.07.002, 2005.

Bargain, A., Robin, M., Le Men, E., Huete, A., and Barillé, L.: Spectral response of the seagrass Zostera noltii with different sediment backgrounds, Aquatic Botany, 98, 45–56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2011.12.009, 2012.

Barillé-Boyer, A-L., Haure, J., and Baud, J-P.: L'ostréiculture en Baie de Bourgneuf. Relation Entre La Croissance Des Huîtres Crassostrea Gigas et Le Milieu Naturel: Synthèse de 1986 à 1995, https://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00000/1633/ (last access: January 2026), 1997.

Benyoucef, I., Blandin, E., Lerouxel, A., Jesus, B., Rosa, P., Méléder, V., Launeau, P., and Barillé, L.: Microphytobenthos interannual variations in a north-European estuary (Loire estuary, France) detected by visible-infrared multispectral remote sensing, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 136, 43–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2013.11.007, 2014.

Berg, P., Risgaard-Petersen, N., and Rysgaard, S.: Interpretation of Measured Concentration Profiles in Sediment Pore Water, Limnology and Oceanography 43, 1500–1510, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1998.43.7.1500, 1998.

Bernhard, J. M. and Geslin, E.: Introduction to the Special Issue entitled “Benthic Foraminiferal Ultrastructure Studies”, Marine Micropaleontology, 138, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2017.11.002, 2018.

Berthelot, M. P. E.: Répertoire de Chimie appliquée, vol. 1. 284–293, https://books.google.fr/books?id=hsRQAQAAMAAJ (last access January: 2026), 1859.

Bird, C., LeKieffre, C., Jauffrais, T., Meibom, A., Geslin, E., Filipsson, H. L., Maire, O., Russell, A. D., and Fehrenbacher, J.: Heterotrophic Foraminifera Capable of Inorganic Nitrogen Assimilation, Frontiers in Microbiology 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.604979, 2020.

Blanchard, G. F., Agion, T., Guarini, J. M., Herlory, O., and Richard, P.: Analysis of the short-term dynamics of microphyto-benthos biomass on intertidal mudflats, in: Functioning of microphytobenthos in estuaries, edited by: Kromkamp, J. C., de Brouwer, J. F. C., Blanchard, G. F., Forster, R. M., and Créach, V., Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Amsterdam, 85–97, https://www.vliz.be/imisdocs/publications/138754.pdf (last access January 2026), 2006.

Bouchet, V. M. P., Debenay, J.-P., Sauriau, P.-G., Radford-Knoery, J., and Soletchnik, P.: Effects of short-term environmental disturbances on living benthic foraminifera during the Pacific oyster summer mortality in the Marennes-Oléron Bay (France), Marine Environmental Research, 64, 358–383, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2007.02.007, 2007.

Brito, A. C., Benyoucef, I., Jesus, B., Brotas, V., Gernez, P., Mendes, C. R., Launeau, P., Dias, M. P., and Barillé, L.: Seasonality of microphytobenthos revealed by remote-sensing in a South European estuary, Continental Shelf Research, 66, 83–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2013.07.004, 2013.

Brotas, V., Cabrita, T., Portugal, A., Serôdio, J., and Catarino, F.: Spatio-temporal distribution of the microphytobenthic biomass in intertidal flats of Tagus Estuary (Portugal), in: Space Partition within Aquatic Ecosystems, edited by: Balvay, G., Springer Netherlands, 93–104, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0293-3_8, 1995.

Burdige, D. J.: Geochemistry of Marine Sediments, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-09506-6, 2006.

Buzas, M. A., Hayek, L.-A., Jett, J. A., and Reed, S. A.: Pulsating Patches: History and Analyses of Spatial, Seasonal, and Yearly Distribution of Living Benthic Foraminifera, Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, https://doi.org/10.5479/si.19436688.97, 2015.

Carter, S. C., Paytan, A., and Griffith, E. M.: Toward an Improved Understanding of the Marine Barium Cycle and the Application of Marine Barite as a Paleoproductivity Proxy, Minerals, 10, 421, https://doi.org/10.3390/min10050421, 2020.

Cavalier-Smith, T.: The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa, International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 52, 297–354, https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-52-2-297, 2002.

Cesbron, F., Geslin, E., Kieffre, C. L., Jauffrais, T., Nardelli, M. P., Langlet, D., Mabilleau, G., Jorissen, F. J., Jézéquel, D., and Metzger, E.: Sequestered Chloroplasts in the Benthic Foraminifer Haynesina germanica: Cellular Organization, Oxygen Fluxes and Potential Ecological Implications, Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 47, 268–278, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.47.3.268, 2017.

Chronopoulou, P. M., Salonen, I., Bird, C., Reichart, G.-J., and Koho, K. A.: Metabarcoding insights into the trophic behaviour and identity of intertidal benthic foraminifera, Frontiers Microbiology, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01169, 2019.

Clark, K. B., Jensen, K. R., and Stirts, H. M.: Survey for functional kleptoplasty among west Atlantic Ascoglossa (= Sacoglossa) (Mollusca: Opisthobranchia), The Veliger, 33, 339–345, 1990.

Clarke, K. R. and Gorley, R. N.: User manual/tutorial, Primer-E Ltd., Plymouth 93, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235425881_Primer_v6_User_ManualTutorial (last access: January 2026), 2006.

Daché, E., Dessandier, P-A., Radhakrishnan, R., Foulon, V., Michel, L., de Vargas C., Sarrazin, J., and Zeppilli, D.: Benthic foraminifera as bio-indicators of natural and anthropogenic conditions in Roscoff Aber Bay (Brittany, France), PLoS ONE, 19, e0309463, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309463, 2024.

Darling, K. F., Schweizer, M., Knudsen, K. L., Evans, K. M., Bird, C., Roberts, A., Filipsson, H. L., Kim, J.-H., Gudmundsson, G., Wade, C. M., Sayer, M. D. J., and Austin, W. E. N.: The genetic diversity, phylogeography and morphology of Elphidiidae (Foraminifera) in the Northeast Atlantic, Marine Micropaleontology, 129, 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2016.09.001, 2016.

Daviray, M., Geslin, E., Risgaard-Petersen, N., Scholz, V. V., Fouet, M., and Metzger, E.: Potential impacts of cable bacteria activity on hard-shelled benthic foraminifera: implications for their interpretation as bioindicators or paleoproxies, Biogeosciences, 21, 911–928, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-21-911-2024, 2024.

Debenay, J.-P.: Distribution des foraminifères vivants et des tests vides en Baie de Bourgneuf, PhD Thesis, Université de Paris VI, 196 pp., 18 pl, https://www.sudoc.fr/042141923 (last access: January 2026), 1978.

Debenay, J.-P. and Guillou, J.-J.: Ecological transitions indicated by foraminiferal assemblages in paralic environments, Estuaries, 25, 1107–1120, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02692208, 2002.

Debenay, J.-P., Guillou, J.-J., Redois, F., and Geslin, E.: Distribution Trends of Foraminiferal Assemblages in Paralic Environments, in: Environmental Micropaleontology: The Application of Microfossils to Environmental Geology, edited by: Martin, R. E., Springer US, 39–67, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4167-7_3, 2000.