the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Morphometric divergence in Cyprideis (Ostracoda) during the Middle and Late Miocene of the Central Paratethys realm

Martin Gross

Dušan Starek

A morphometric outline analysis of the brackish-water ostracod Cyprideis examines a 2.0-million-year period during which the Central Paratethys region underwent significant geographic and environmental transformations.

Based on hingement anatomy, the polymorphic Cyprideis pannonica, characterized by considerable variation in valve outline and size, inhabited the marginal marine environments of the Central Paratethys during the late Middle Miocene. With the transition to lacustrine conditions in the Late Miocene, Cyprideis colonized the brackish Lake Pannon and adapted to different water depths. However, compared to its Middle Miocene ancestors, it lost its total variability in outline due to a fragmented lacustrine environment.

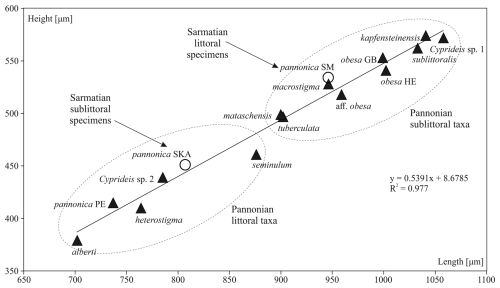

Less than 0.5 million years after the lake's formation, a regression event eliminated littoral C. pannonica morphotypes. When a new transgressive cycle began, these morphotypes were replaced by neoendemic littoral taxa, which exhibited only limited morphometric similarity to their ancestors and contemporaneous sublittoral relatives. While littoral taxa evolved rapidly in terms of outline, sublittoral species increased in size, consistent with Bergmann's rule, and were more conservative in the outline, maintaining a higher degree of morphometric similarity to their ancestors.

Despite a physiological adaptation to brackish waters, Cyprideis were outnumbered in Lake Pannon by primarily freshwater candonins and marine/brackish leptocytherids. It is concluded that lacustrine habitat heterogeneity and tectonic activity in the Central Paratethys had impacted the adaptive radiation and the polycyclic evolution of Cyprideis.

- Article

(9405 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(705 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Long-lived lakes serve as biodiversity hotspots for freshwater species and marine-like animals. However, only certain ostracod groups exhibit a higher predisposition for speciation in these environments (Martens, 1994). Adaptive radiation can occur from ancestors inhabiting both the lake and the surrounding biotopes. This radiation is generally considered adaptive, influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors, and strongly driven by tectonic activity and climatic changes (von Rintelen et al., 2004; Schön and Martens, 2004). New species can evolve rapidly (Martens et al., 1994) due to habitat fragmentation (Altizer et al., 2003; Gross et al., 2013), often forming small populations with limited geographical distribution (Cohen, 1994).

The most favourable period for adaptive radiation occurs when a species invades a new or unoccupied niche, competing with other species. Successive morphological adaptations are associated with distinct habitat preferences, dietary shifts (Schluter, 1996), sexual selection pressures, time-related factors, and developmental and historical constraints (Schön and Martens, 2004). However, highly fluctuating environmental conditions can hinder morphological changes, leading species to remain in morphological stasis or experience only occasional evolutionary shifts, particularly in shallow-water taxa and temperate zones (Cronin, 1985; Sheldon, 1996). When environmental conditions exceed critical thresholds (Sheldon, 1996), the surviving lineages may have a greater potential to develop novel phenotypes (Regan et al., 2003).

This theoretical framework is applied here to the Miocene long-lived Lake Pannon fauna. We focus on the morphometric traits of calcitic ostracod valves, examining both intrinsic and extrinsic factors that influence their morphological variability in terms of outline and hingement, particularly in the brackish-water mussel-shrimp Cyprideis. This genus first appeared in the Central Paratethys region at the end of the Middle Miocene and subsequently established itself in Lake Pannon during the Late Miocene (Kollmann, 1960). Our analysis covers a period of approximately 2.0 million years, during which Cyprideis exhibited adaptive processes while the geographical region underwent two significant ecological and geographical transformations.

Cyprideis is a benthic, euryhaline genus primarily adapted to brackish environments but capable of tolerating a wide range of salinity conditions (Van Harten, 1990). It rapidly became cosmopolitan following its emergence in the Late Oligocene (Malz and Triebel, 1970; Kadolsky, 2008) and has been found in numerous endemic and morphologically highly variable populations in non-marine basins across South America, Europe, and Türkiye (Bassiouni, 1979; Jiříček, 1985; Krstić, 1985; Whatley et al., 1998; Ligios and Gliozzi, 2012; Gross et al., 2013, 2014). The morphologically most spectacular species radiation is known from Lake Tanganyika (Wouters and Martens, 2001).

In Europe, Cyprideis spread in the Middle Miocene, forming the Mediterranean phyletic lineage and the Paratethyan phyletic lineage represented by the endemic species of Lake Pannon (Gliozzi et al., 2017).

The living species, Cyprideis torosa (Jones, 1850), originated in the Late Miocene Mediterranean from the Mediterranean phyletic lineage (Gliozzi et al., 2017) and is now widely distributed in coastal oligo-miohaline (brackish) waters across Europe, Asia, and Africa (Wouters, 2002, 2017). As a “pioneer” species, it possesses a highly efficient osmoregulatory system, enabling it to survive in both freshwater and hypersaline environments where salinity can reach up to 200 g L−1 (Aladin and Potts, 1996; Gamenick et al., 1996). Its ability to tolerate a wide range of temperatures, oxygen, salinity, and substrate conditions (De Deckker and Lord, 2017) significantly influences the shape, size, and ornamentation of the valve. These variations are phenotypic responses to environmental conditions or may be induced by physiological and genetic changes (Kilenyi, 1972; Van Harten, 1975, 2000; Bodergat, 1983, 1985). Consequently, they are not considered reliable diagnostic characteristics for C. torosa (Wouters, 2002, 2017). However, some of these characteristics, such as details of the hinge and posteroventral spines, can be significant for the taxonomy of endemic species (Gross et al., 2008, 2014).

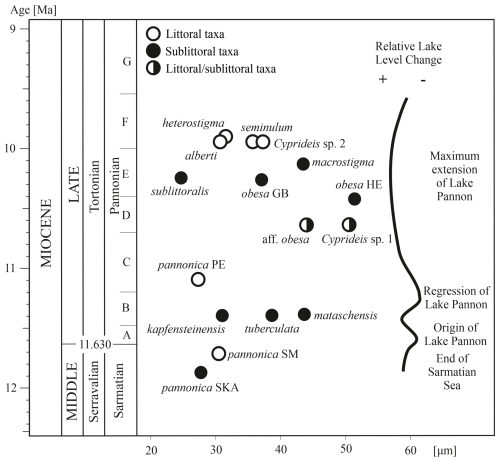

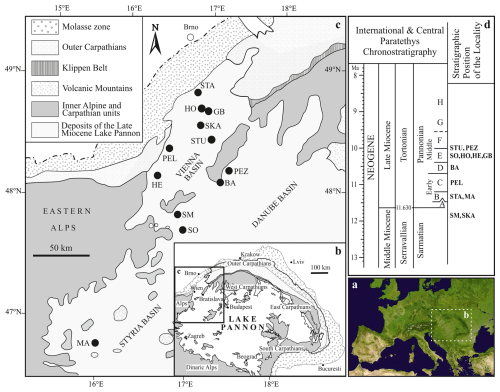

Figure 1Geographical location of the studied localities. The biozonation of the Pannonian is based on brackish molluscs and is divided into zones A–H (sensu Papp, 1951), reflecting the ecological preferences of the Lake Pannon meiofauna (Magyar et al., 1999; Harzhauser and Piller, 2007). Stratigraphic position of the localities based on Geary et al. (2010), Gross et al. (2008), Harzhauser et al. (2002, 2003, 2009), Harzhauser and Tempfer (2004), Magyar et al. (2007), Pipík (1998, 2007), Pipík et al. (2004), Starek et al. (2010), and Šujan et al. (2021). Abbreviations: BA: Bratislava; GB: Gbely; HE: Hennersdorf; HO: Hodonín; MA: Mataschen; PEL: Pellendorf; PEZ: Pezinok; SM: Sankt Margarethen; SKA: Skalica; SO: Sopron; STA: Stavěšice; STU: Studienka.

C. torosa reproduces sexually, exhibiting pronounced sexual dimorphism in valve morphology. Females possess a brood pouch within the carapace, which protects eggs and juveniles during the first ontogenetic stage (Meisch, 2000). Ontogenetic development is positively correlated with water temperature, and under optimal conditions, Cyprideis can form dense local populations. As a microphagous detritus feeder, its abundance depends on the bacterial decomposition of organic matter (Heip, 1976).

At the end of the Middle Miocene, a semi-isolated epicontinental sea – the Sarmatian Sea – developed in the Central and Eastern Paratethys regions, characterized by an endemic and significantly impoverished fauna lacking most stenohaline taxa (Harzhauser et al., 2007; Fig. 1). In the Central Paratethys, fine siliciclastic sedimentation gave way to alkaline, carbonate-oversaturated deposition. Oolites and coquina-dominated sands spread across nearshore environments and shallow shoals (Harzhauser and Piller, 2004a, b). The early Sarmatian polychaete–bryozoan communities collapsed and were replaced by unique foraminiferal build-ups, contributed by the sessile genus Sinzowella (Harzhauser et al., 2007). The latest Sarmatian was marked by the final occurrence of brachyhaline and marine ostracods. During this time, Cyprideis appeared for the first time in marginal marine environments (Jiříček, 1985; Krstić, 1985).

Paleogeographical changes between the Middle and Late Miocene led to a significant reduction and fragmentation into smaller water bodies, a drop in salinity, faunal turnover, and the emergence of an isolated brackish Lake Pannon (Geary et al., 1989; Magyar et al., 1999, 2025). In its early phase (zones A, B), the lake's chemical composition remained similar to the Sarmatian one in terms of alkalinity, carbonate content, and sulfur isotopic composition (Mátyás et al., 1996; Harzhauser et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2023). The formation of Lake Pannon without deep-water subbasins (Magyar et al., 1999) posed a challenge for molluscs (Müller et al., 1999) and ostracods, which evolved from a few surviving marine and freshwater lineages (Magyar et al., 2025). They adapted to ecological niches characterized by sandy deltaic and clay-rich offshore sedimentation in the north half of the lake and carbonatic precipitation in the south of the lake, with relatively stable brackish salinity (Geary et al., 1989; Magyar et al., 1999).

Less than 0.5 million years later (zone C), a regression led to the deposition of thick sandy sedimentary bodies (Kováč et al., 1998). However, between approximately 11.04 and 9.8 million years ago, Lake Pannon expanded and reached its maximum extent due to intensified basin subsidence (zone E; Magyar et al., 2007). Benthic animal communities, differentiated by depth, occupied fully oxic and brackish environments (Cziczer et al., 2009) under a temperate climate with distinct seasonality (Harzhauser et al., 2023). In some areas, riverine discharge and anoxic events influenced the bottom meiofauna (Harzhauser et al., 2007; Magyar et al., 2007; Starek et al., 2010).

Following this period, the sudden retreat of Lake Pannon (zones F–H) led to the formation of extensive alluvial lowlands, ephemeral lakes, and swamps (Harzhauser and Tempfer, 2004; Harzhauser et al., 2004). The progressive freshening of the lake (Geary et al., 1989; Neubauer et al., 2016) resulted in local extinctions and the migration of the brackish fauna to the southern part of Lake Pannon and the Eastern Paratethys (Pipík, 2007; Cziczer et al., 2009; Neubauer et al., 2016).

4.1 Sampling and measurement strategy

Our sampling strategy aimed to encompass all types of depositional environments with well-defined palaeoecological settings along the western margin of Lake Pannon, covering a stratigraphic range from the pre-lacustrine late Sarmatian to the lacustrine middle Pannonian (approximately 2.0 million years; Fig. 1, Table S1). All collected samples were dried naturally in the laboratory, washed through a 0.09 mm sieve, and examined under a stereo microscope for species identification. The relative abundance of Cyprideis was calculated based on all adult ostracod valves in the sieve residue to determine their dominance in the paleocommunity.

Only well-preserved, transparent, or milky female right valves were used for outline analysis. Species identification was based on Kollmann's revision of the genus (Kollmann, 1960) and on taxonomic studies of Cyprideis from the Vienna and Styrian Basins (Pokorný, 1952; Gross et al., 2008). A list of the species treated and their descriptions can be found in Table S2. Typically, more than 20 valves of each species were selected (Table S3); however, for Cyprideis sp. 1, only 14 valves were available. Valve lengths and heights (Fig. 2a) were measured using EclipseNET software (version 1.20), determining the maximum distance between two parallel lines: one tangential to the lowest point of the ventral margin and the other tangential to the highest point of the dorsal margin.

Figure 2(a) Measured parameters of the right valve (external view). The anterior and posterior spines were removed using graphical software. (b) The anterior socket and its hingement on the left valve (internal view). (c) Approximation of the valve outline using Morphomatica software with B-splines drawn over the outline. The control points of the corresponding control polygon are numbered and used to display differences between species for total area (all points), ventral area (points v1–v7), and dorsal area (points d1–d7).

SEM images of left valves in the internal lateral view were analysed to examine the arrangement and subtle variations of the hinge structure (Table S2), following the terminology of Van Morkhoven (1962, p. 79). The maximum width of the anterior socket (Fig. 2b) was measured from SEM images, spanning from the proximal part of the anterior slip bar to the distal part of the anterior socket, which is bordered by a shallow groove above it.

4.2 Computation of the outline

Valves were photographed in external lateral view using a Nikon light microscope and a Nikon digital camera, then processed with TPS-dig software (version 1.40; Rohlf, 2004; Fig. 2a). Morphometric analysis of the outlines was subsequently conducted using Morphomatica software (version 1.6; see Brauneis et al., 2006a, b for details), which is based on the B-splines approach. This method is particularly suited for smoothing and analysing slightly ornamented ostracods that lack distinct landmarks (for a detailed methodological approach, see Minati et al., 2008).

Mean shape outlines of the original TPS data were computed using Morphomatica 1.6, allowing the valve outlines to be displayed in a format suitable for visualizing shape differences. Multivariate statistical analyses were performed using the Primer 6 software package (Clarke and Gorley, 2006). Non-metric multidimensional scaling (n-MDS) was used to display differences between the normalized and non-normalized mean shape outlines. Additionally, analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) was conducted with a one-way layout to test the null hypothesis that no differences exist between Cyprideis species in the approximated B-spline curves.

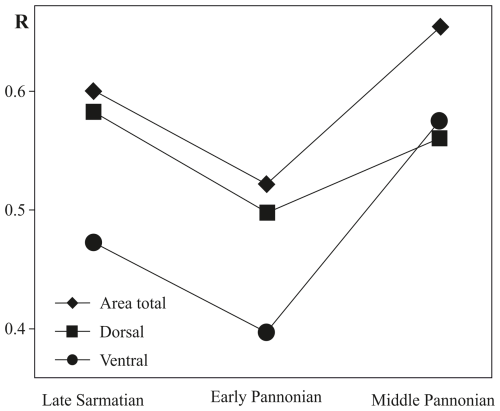

The R value in ANOSIM ranges from 1, indicating complete separation of samples, to 0, meaning no significant differences among samples. According to Clarke and Gorley (2001), R values of R≥0.75 indicate well-separated groups, suggest overlapping but distinct groups, and R≤0.5 denotes barely separable groups.

Since the general shape of the ostracod valve is influenced by the extension and arrangement of its inner soft parts (Van Morkhoven, 1962), a one-way layout ANOSIM test is also applied to assess differences between species at the same stratigraphic level for total area, ventral area, and dorsal area (Brauneis et al., 2006a; Fig. 2a, c). A standardized principal component analysis (PCA) eliminates the horseshoe effect and illustrates the morphometric space occupied by all analysed specimens and its shift over time.

5.1 Shape differences

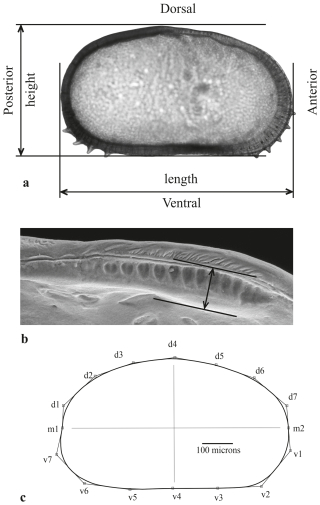

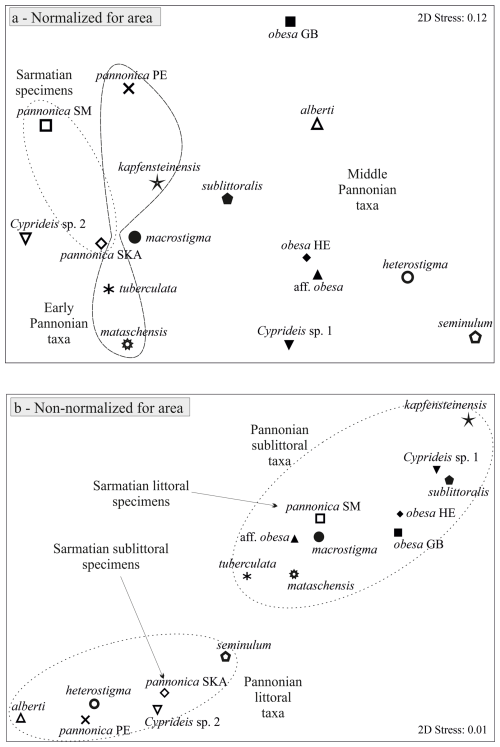

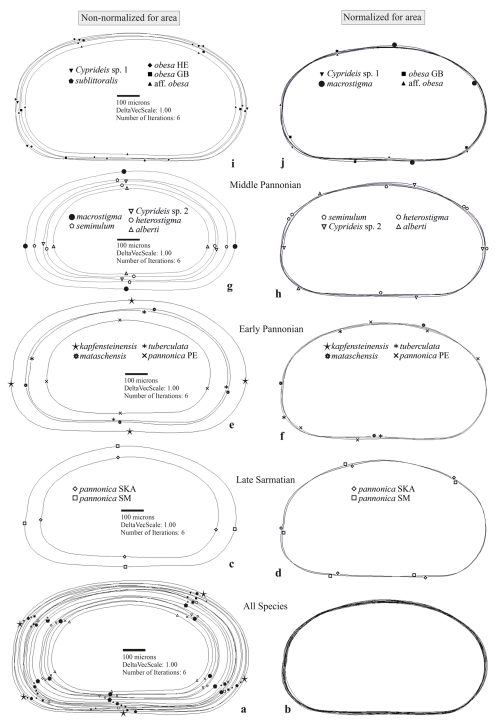

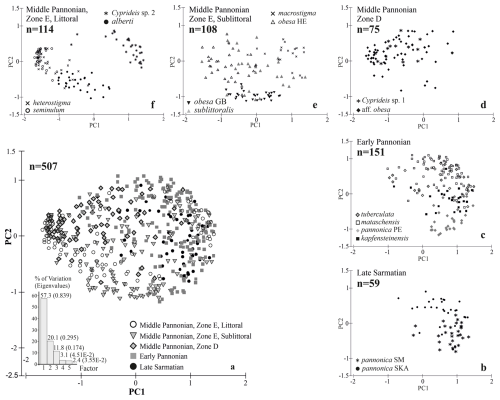

Mean outlines, normalized for area and placed in a multidimensional space, display an increasing trend in variability from the Sarmatian to the middle Pannonian (Fig. 3a). This variation is evident along the entire outline (Fig. 4b, d, f, h, j). The early Pannonian normalized outlines of C. kapfensteinensis, C. pannonica, C. tuberculata, and C. mataschensis closely resemble those of the Sarmatian C. pannonica, but morphospace variability increases within the group (Fig. 3a). Middle Pannonian taxa exhibit significant variability, occupying nearly the entire multidimensional space defined for the studied Cyprideis species. Cyprideis sp. 2, C. macrostigma, and C. sublittoralis are closely related to the Sarmatian and early Pannonian Cyprideis groups, while C. obesa, C. alberti, C. aff. obesa, C. heterostigma, Cyprideis sp. 1, and C. seminulum differ considerably, showing a large morphometric distance from the older taxa.

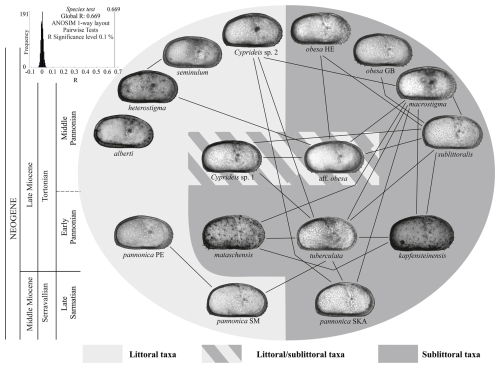

Sarmatian C. pannonica are closely grouped in the normalized n-MDS plot but are relatively distant in the non-normalized for area n-MDS plot, which separates the species into two clusters based on mean species size and water depth (Fig. 3b). The upper-right corner of the plot regroups larger species found in sublittoral deposits, alongside C. aff. obesa and Cyprideis sp. 1, which are known from littoral/sublittoral environments. In contrast, the lower-left corner regroups smaller species from littoral sediments characterized by fluctuating environmental conditions. Interestingly, Sarmatian C. pannonica shows an inverse position concerning water depth (Table S1). The mean outline differs in size (Fig. 4c) and exhibits variation along the ventral and dorsal margins, remaining parallel at the posterior and nearly identical at the anterior (Fig. 4d).

The early Pannonian Cyprideis species (Fig. 4e, f) exhibit variations in size, with noticeable differences in shape along the dorsal, posterior, and ventral margins. This variability is particularly pronounced in C. mataschensis, C. tuberculata, and C. pannonica, whereas the mean outline of C. kapfensteinensis falls within the calculated range of shape differences. A trend of increasing differentiation in size and shape continues into the middle Pannonian taxa, where variations are also observed along the anterior margin (Fig. 4g–j). The greatest area of deviation occurs among littoral taxa, with all species in this group contributing to the variability (Fig. 4g, h). Among sublittoral taxa, C. aff. obesa, C. obesa GB, and Cyprideis sp. 1 are primarily responsible for variability along the posterior and ventral margins, while C. macrostigma contributes to variations along the dorsal, anterior, and ventral margins (Fig. 4j). The ANOSIM (Fig. 5) of species from the same stratigraphic level reveals a decrease in variability in the total area from the late Sarmatian (R=0.6) to the early Pannonian (R=0.521), followed by a sharp increase in the middle Pannonian (R=0.654).

Figure 3n-MDS plot for mean Cyprideis specimens: (a) normalized for area, (b) non-normalized for area.

Figure 4Mean outlines of the right valves and differences in shape: (a, c, e, g, i) non-normalized for area, (b, d, f, h, j) normalized for area.

Figure 5ANOSIM pairwise test of approximated B-spline curves comparing species within the same stratigraphical level for total area, ventral area, and dorsal area, as well as their changes over time. The significance level for all tests is p<0.1 %.

Superimposed mean outlines of all taxa display variations in size (a) and in differences in outline shape (b). The time slices indicate an increase in shape disparity (right column) and the area of deviation (left column) over time (c–j). Symbols representing mean normalized outlines indicate only the species contributing to variability in specific outline areas. For better readability of the large taxa outlines (i), the non-normalized outline of C. macrostigma is plotted alongside the small middle Pannonian taxa (g).

This trend is also observed in the dorsal and ventral areas, with a significant rise in variability in the ventral area (R=0.573) from the early to middle Pannonian.

The differences between Cyprideis species at the same stratigraphic level, as represented by approximated B-spline curves for total, ventral, and dorsal areas, are evident. Therefore, the null hypothesis can be rejected.

5.2 Size changes of the anterior socket

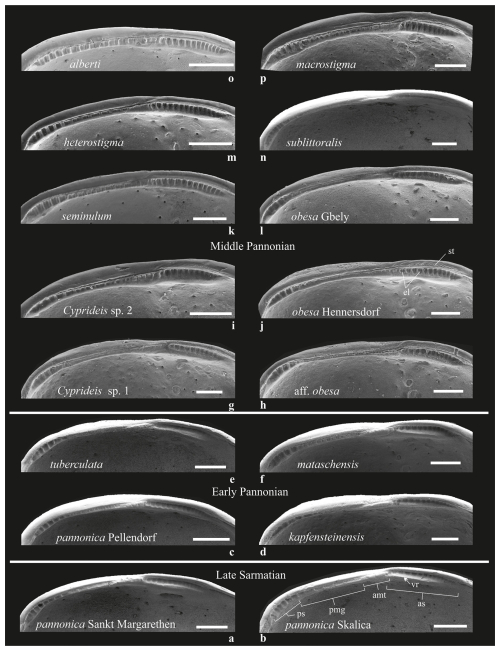

The size and morphology of the anterior socket vary, with the most significant differentiation observed in middle Pannonian species (Fig. 6). This parameter exhibits non-linear growth over time, forming a flower-like shape. The socket size in Sarmatian species ranges from 28–30 µm, while in early Pannonian species, it increases, ranging from 27–44 µm.

In littoral species from zone E/F, the anterior socket size varies between 30 and 37 µm, whereas sublittoral taxa from the same zone show the highest variability, ranging from 25–51 µm. The largest anterior sockets are found in the sublittoral species C. obesa HE, C. macrostigma, and C. mataschensis. However, two other large sublittoral species, C. sublittoralis and C. kapfensteinensis, have narrower anterior sockets.

The socket width does not correlate with species size or water depth. Instead, it has an independent taxonomic and evolutionary significance.

5.3 Polymorphism in the Sarmatian Sea

Sarmatian paleopopulations of C. pannonica likely occurred in the marginal facies of the late Sarmatian Sea (Cernajsek, 1974; Krstić, 1985). The two studied paleopopulations of C. pannonica, originating from different environments (Table S1, Fig. 7b), exhibit a relatively high statistical separation (R=0.6), indicating some overlap but also clear species differentiation (Clarke and Gorley, 2001, 2006). However, this differentiation is not supported by variations in hingement composition. Both Sarmatian paleopopulations share identical hingements, with only minor variations in the anteromedian element – very fine crenulations in the lacustrine-brackish environment (Table S2, Fig. 8a, Table S1, Sankt Margarethen) and a bilobate structure in the brachyhaline environment (Fig. 8b, Skalica). These differences are interpreted here as intraspecific variations.

Figure 7A graphical representation of the morphospace occupied by all analysed specimens using PCA (a). The morphospace of the Sarmatian Cyprideis (b) expanded with the formation of Lake Pannon in the early Pannonian, although the general valve outline remained conservative (c). A subsequent shift in morphospace variability occurred in response to the basin's re-flooding and the increased ecological heterogeneity of middle Pannonian Lake Pannon (d–f).

5.4 Emergence of Lake Pannon – loss of morphometric variability

C. pannonica shares the same hinge arrangement as its Sarmatian ancestors and exhibits distinct morphometric differences from contemporaneous sublittoral Cyprideis species (Figs. 3, 9). The early Pannonian sublittoral taxa (C. tuberculata, C. kapfensteinensis, C. mataschensis) show minimal morphometric variation and a hinge pattern similar to that of the Sarmatian C. pannonica (Fig. 8c–f). Notably, C. tuberculata displays morphometric similarity to both Sarmatian morphotypes of C. pannonica (Figs. 7, 9).

5.5 The maximal extent of Lake Pannon and species diversity

Cyprideis sp. 1 and C. aff. obesa appeared after the re-flooding of the basin in the middle Pannonian, exhibiting similar outlines (R=0.352) and comparable anterior socket widths. However, C. aff. obesa possesses striae at its socket. Sublittoral Cyprideis from zone E inhabited fully oxygenated basinal clayey environments (C. sublittoralis, C. obesa HE) and silty environments (C. obesa GB) influenced by riverine input. C. macrostigma was found in clayey and silty deposits of the open lake facies (Cziczer et al., 2009).

Figure 8Hingement composition of Lake Pannon Cyprideis (see also Table S2). The basic hingement plan of Sarmatian species (a–b) was also observed in early Pannonian species, albeit with subtle modifications in the anterior and median elements of sublittoral taxa. These changes included small elevations within the crenulation (C. mataschensis) and smoothening to slight crenulation (C. tuberculata) (c–f). In middle Pannonian taxa, the hingement became more robust and coarser, displaying a segmented anteromedian tooth (C. macrostigma, Cyprideis sp. 2, C. alberti), a thinner structure with fine denticulation (C. sublittoralis, Cyprideis sp. 1), or the presence of striae above the anterior socket on the outer lamella (C. obesa HE, C. aff. obesa, Cyprideis sp. 2) (g–p). Abbreviations: amt – anteromedian tooth; as – anterior socket; el – elevations; pmg – posteromedian groove; ps – posterior socket; st – striae; vr – ventral rim. Scale bar 0.1 mm.

ANOSIM separates C. obesa HE from C. obesa GB (R =0.667), supporting their classification as separate species based on the wider anterior socket, the presence of striae (Fig. 8j, l), and differences at the dorsal and ventral margins. In contrast, C. obesa HE is morphometrically identical to C. aff. obesa ( %). Both taxa have very similar hinges differing in the fine elevations of the posterior socket and the width of the posteromedian groove. They probably represent a single species (Table S4).

The outlines of sublittoral taxa were linked to Sarmatian sublittoral and brachyhaline C. pannonica, as well as to early Pannonian sublittoral Cyprideis (Fig. 9). Most of these relationships involve C. macrostigma and C. sublittoralis, whose outlines statistically overlap (R=0.327) but exhibit significantly different hingement (Fig. 8n, p). This suggests minor morphometric differences and a slow gradualistic evolution in outline within the sublittoral habitat.

While sublittoral species are morphometrically conservative, littoral species exhibit a high diversity of outlines. C. heterostigma is closely related to the littoral/sublittoral C. aff. obesa. Cyprideis sp. 2, characterized by a fairly robust segmented anteromedian tooth and striae above the anterior socket, shows similarities to sublittoral Sarmatian, early Pannonian, and contemporaneous sublittoral species. C. alberti is the most distinct among all species (), possessing a hinge structure without an apparent posterior socket and with the same width as the posteromedian groove (Fig. 8o). In contrast, C. heterostigma and C. seminulum exhibit very low statistical separation (R=0.253) and an almost identical hingement; therefore, their species status is based on the sigmoidal ventral margin and narrow furrows in posterior socket observed in C. seminulum (Table S2).

6.1 The ancestor of Lake Pannon Cyprideis

Due to its broad paleoenvironmental tolerance, Sarmatian C. pannonica exhibited notable intraspecific variation in both valve outline and size. A morphometric approach, combined with hingement as an independent taxonomic characteristic, indicates the absence of reproductive barriers and suggests a shared gene pool among Sarmatian C. pannonica paleopopulations.

According to this study, based on the biostratigraphic findings of Kollmann (1960) and Jiříček (1985), C. pannonica was the ancestor of the Cyprideis Paratethyan lineage. Specimens from low-energy brackish marsh environments were bigger and dominated over the freshwater genera Notodromas, Potamocypris, Candonopsis, and Heterocypris (Pipík et al., 2009). Specimens from the brachyhaline sublittoral outer estuary were smaller and associated with Cyamocytheridea, Hemicytheria, Loxoconcha, and Euxinocythere (Fordinál and Zlínska, 1998). It exhibited the same negative size–salinity relationship (Van Harten, 1975; Boomer et al., 2017; Fig. 10) and occurred in ostracod associations with a composition similar to that of C. torosa (Frenzel, 1991; Pint and Frenzel, 2017).

Based on hinge anatomy, only one species – C. pannonica – inhabited the Sarmatian Sea, displaying significant size variation (SD of length: ±36.02 for C. pannonica SKA and ±35.85 for C. pannonica SM; Table S3). The large C. pannonica SM thrived in the low-energy brackish marsh, comprising 53 % of the sieve residuum. In contrast, smaller specimens (C. pannonica SKA) were subdominant in the brachyhaline sublittoral outer estuary, making up only 13 % of the sieve residuum.

Lake Tanganyika is a model example of adaptive radiation. The ancestor of Cyprideis is believed to have originated from an estuarine stock, from which ecological segregation has led to a wide variety of valve ornamentation, while the soft body parts have remained relatively conservative (Wouters and Martens, 2001). However, molecular data indicate that the Cyprideis species flock in Lake Tanganyika is approximately 15 million years old, predating the lake's formation (Schön and Martens, 2012).

Figure 9Graphic presentation of the ANOSIM pairwise test among Lake Pannon Cyprideis. Lines connect paired samples (species) with R≤0.5 (Table S4). A founder effect in early Pannonian Lake Pannon led to the segregation of the polymorphic euryhaline Sarmatian C. pannonica. Water-level changes between Pannonian zones C and D facilitated the gradualistic evolution of sublittoral morphotypes and the rapid evolution of neoendemic littoral taxa, which replaced the paleoendemic C. pannonica. The illustrated species are not drawn to scale.

The similarity in hingement patterns between late Sarmatian and early Pannonian Cyprideis (Fig. 8) suggests that the observed Cyprideis diversity in Lake Pannon resulted from a single colonization event followed by successive radiation. This hypothesis aligns more closely with the model of the Cytherissa species flock – a genus in the same subfamily (Cytherideinae) as Cyprideis – which radiated after the formation of Lake Baikal (Schön and Martens, 2012).

6.2 Adaptation and radiation of Cyprideis in Lake Pannon

Well adapted to brackish and unstable lacustrine environments, C. pannonica survived intensive but short-lived paleogeographical changes between the Middle and Late Miocene. Over time, it became dominant in shallow, brackish sandy littoral habitats transitioning towards the freshwater environment, comprising 83 % of the sieve residuum (locality Pellendorf). C. kapfensteinensis and C. mataschensis coexisted in a sublittoral mesohaline environment. However, C. kapfensteinensis thrived during the interval of highest ostracod diversity, which coincided with the lake deepening and clay sedimentation and salinity above 13 psu (Gitter et al., 2015). In contrast, C. mataschensis was associated with prograding prodelta deposits composed of clay and fine sand (Gross et al., 2008; Gitter et al., 2015) and salinity below 13 psu. Comprising 10 % of the sieve residuum, C. tuberculata inhabited a prodeltaic calcareous silt deposited during a lowstand period (Kováč et al., 1998).

Figure 10Changes in the mean species size of Cyprideis from the late Sarmatian (empty circle) to the middle Pannonian (black triangle). After the Sarmatian, Cyprideis established themselves in Lake Pannon, undergoing speciation into two groups: smaller littoral taxa and larger sublittoral taxa. Species size exhibited a positive correlation with water depth.

A brackish early Pannonian lacustrine environment led to the segregation of polymorphic Sarmatian paleopopulations along a continuous environmental gradient, primarily represented by water depth and salinity changes (Gross et al., 2011). Early Pannonian taxa inhabited littoral and sublittoral biotopes, and despite this adaptation, their overall morphometric variability declined compared to their ancestor (Fig. 5) because subsidence of the peripheral subbasins had ceased, and Lake Pannon consisted of relatively shallow, occasionally dry, and temporarily fragmented water bodies (Magyar et al., 1999).

The bottle-necked Middle Miocene paleopopulations adapted to the diverse habitats of Lake Pannon, marking the first phase of the founder effect. A second environmental fluctuation in the Late Miocene (zone C), occurring shortly after the lake's formation, coincided with the retreat of Lake Pannon. This event led to the disappearance of the pre-Lake Pannon littoral Cyprideis morphotype and other species that had persisted since the Sarmatian, such as Hemicytheria omphalodes (Pipík, 2007).

During the subsequent transgression (the second phase of the founder effect) and rapid subsidence, which formed multiple deep subbasins (Magyar et al., 1999; Šujan et al., 2021), the lake expanded, flooding the vast area inside the forming Carpathian arc. This expansion allowed significant species radiation of all ostracod genera, including Cyprideis, throughout the entire area of Lake Pannon (Sokač, 1972; Krstič, 1985). This process isolated surviving sublittoral early Pannonian Cyprideis and led to the speciation of new sublittoral taxa with low morphometric variability – C. obesa, C. macrostigma, and C. sublittoralis. The transgression created new habitats, fostering the adaptive radiation of littoral neoendemics (Fig. 9). The resulting vacant littoral environment increased the speciation rate, leading to the emergence of four species – C. alberti, C. seminulum, C. heterostigma, and Cyprideis sp. 2. One of them, C. alberti, formed a hinge (Fig. 8o) that differs from the typical Cyprideis plan, and its anteroventral margin is covered with numerous densely spaced short spines. This species may represent a new Cyprideis subgenus or genus. These taxa appeared suddenly at the onset of the transgressive cycle, displaying limited morphometric similarity to sublittoral species. They replaced C. pannonica in the littoral community, becoming dominant in eutrophic estuaries (C. heterostigma, comprising 60 % of the sieve residue) and brackish shallow lagoons (C. seminulum, C. alberti, and Cyprideis sp. 2, collectively comprising 83 % of the sieve residue; Pipík, 1998, 2007; Pipík et al., 2004). Thus, the number of Cyprideis species increased in the entire area of Lake Pannon.

6.3 Speciation in response to biotic factors

Pre-Lake Pannon and Lake Pannon Cyprideis exhibit pronounced sexual dimorphism, which, along with their dispersal ability, is closely linked to the evolutionary success of ostracods in long-lived lakes (Martens et al., 1994). Throughout the 7.5-million-year-old history of Lake Pannon, Cyprideis formed approximately 30 species (Kollmann, 1960; Sokač, 1972; Krstič, 1985). Despite being physiologically adapted to brackish waters, they were outnumbered (Sokač, 1972; Krstič, 1985; Cziczer et al., 2009) by primarily freshwater candonins (Meisch, 2000) and marine/brackish leptocytherids (Smith and Horne, 2002), all of which reproduce sexually and have a benthic mode of life. Although Cyprideis were abundant and displayed morphologically spectacular taxa, they were also outnumbered by Candonidae in Lake Tanganyika (Martens, 1994). Once again, their osmoregulatory system did not provide an advantage that would make them the most diversified taxon in this alkaline lake.

Care for eggs and juveniles of the first stage within a brood pouch, as observed in Lake Pannon Cyprideis females (see Van Harten, 1990, p. 195), seems to be less advantageous for the rate of speciation in long-lived lake environments compared to taxa that lack a brood pouch, do not provide care for offspring, and have high fecundity (see Cohen and Johnston, 1987). Gross et al. (2013) suggest that this reproductive mode inherits a reproductive advantage and/or facilitates dispersal and colonization in a patchy structured fluvio-lacustrine environment, whereas Martens (1994) emphasizes its role in interspecies competition. A reduction in competition, linked to limited dispersal ability in lake habitats, has been observed in the brood-pouch-bearing subfamily Timiriaseviinae (Colin and Danielopol, 1979). The extant Timiriaseviin genus Gomphocythere also has a limited number of endemic species in long-lived lakes (Park and Martens, 2001), whereas the Limnocytherinae, a subfamily of the same family as Timiriaseviinae but lacking a brood pouch, have undergone extensive radiation in long-lived lakes (Martens, 1994).

A possible morphological response to predator pressure (Geary et al., 2002) cannot be effectively tested in Cyprideis valves, as they do not exhibit significant ornamental modifications, increased calcification, or clear traces of predation compared to Cyprideis from Lake Tanganyika (Wouters and Martens, 2001).

We suggest that the Cyprideis salinity tolerance and brood care were not the main factors in the speciation of the genus in Lake Pannon.

6.4 Speciation in response to abiotic factors

Lake Pannon, a long-lived lake, was divided by geographical barriers into a system of depocentres, reaching depths of up to 1000 m (Balázs et al., 2018). Habitat heterogeneity increased significantly during the maximum expansion of the lake (∼ 10 Ma), marked by diverse depositional environments, including alluvial and fluvial facies, ephemeral lakes, swamps, and subaquatic delta plains, which gradually transitioned into offshore pelitic facies (Harzhauser and Tempfer, 2004; Šujan et al., 2021). In these environments, bottom colonization was influenced by oxygen availability (Starek et al., 2010). Morphologically stagnant gastropod taxa in Lake Pannon experienced rapid evolutionary changes, primarily driven by shifts in salinity (Geary, 1990; Geary et al., 1989). Gitter et al. (2015) also propose that changes in salinity functioned as a major driver of speciation in Cyprideis, as mid-Pannonian conditions were characterized by oligo- to miohaline salinities (Cziczer et al., 2009), which corresponded to the ecological optimum of Cyprideis (Meisch, 2000). However, despite these seemingly favourable conditions, members of the subfamily Candoninae – primarily freshwater ostracods (Meisch, 2000) – proliferated at the expense of Cyprideis.

Regarding the salinity of the water environment and the degree of morphometric variability, the two most significant radiations of Cyprideis were observed in the alkaline freshwater Lake Tanganyika (Wouters and Martens, 2001) and in the Miocene freshwater or episodically saline-influenced basins of western Amazonia (Whatley et al., 1998; Gross et al., 2013; Gross and Piller, 2020). Numerous endemic species are known from Late Miocene basins in Türkiye, where warm temperate conditions (Akgün et al., 2007) and the isolation of the basins fostered morphologically diverse Cyprideis species (Bassiouni, 1979; Rausch et al., 2020). In contrast, in the modern Ponto-Caspian region – including the Black Sea, the long-lived Caspian Sea, and Aral Lake – where Lake Pannon ostracod descendants found favourable ecological conditions (Pipík, 2007; Boomer, 2012), no new Cyprideis species evolved, and it did not even become a refuge for the Paratethyan Cyprideis phyletic lineage. This region is settled only by the morphologically variable C. torosa (Boomer, 2012; Wouters, 2017; Tkach, 2024).

This suggests that water salinity is not a primary factor driving the radiation of this brackish-water genus in lakes.

In the case of Sarmatian C. pannonica, bigger specimens lived in the shallow stagnant marsh – presumably a warmer environment – while smaller specimens lived in the estuary with flowing water. This pattern corresponds to Heip's (1976) observation of a positive correlation between ontogenetic development and water temperature in C. torosa. The Pannonian Cyprideis were small in various littoral environments and larger in clay/silt sublittoral environments (Fig. 10). At the population level, such changes are typically linked to food supply and temperature (Atkinson and Sibly, 1997; Feniova et al., 2013).

This depth–size relationship evolved in Lake Pannon over 1.5 million years. We believe that the temperature of the aquatic environment played a principal role in the adaptation of Cyprideis. It is known that Lake Pannon was deep, and faunae inhabited the environment even at depths of up to 80 m (Cziczer et al., 2009). The water temperature in the 0–100 m water column could have been relatively stable throughout the year, as in the case of tropical Lake Tanganyika (Plisnier et al., 1999), or it could have fluctuated, as in the case of the Caspian Sea (Jamshidi, 2017), which spans from a warm dry temperate zone to a cool dry temperate zone (Duveillera et al., 2020).

The Central Paratethys region gradually transitioned from a subtropical climate in the Middle Miocene to a warm temperate climate with distinct seasonality in the Late Miocene (Jiménez-Moreno, 2006; Harzhauser et al., 2023). Therefore, the climatic conditions of Lake Pannon are comparable to those of the southern part of the Caspian Sea, where the thermocline is situated approximately 50 m below the water surface (Tuzhilkin and Kosarev, 2005; Jamshidi, 2017). Above the thermocline, summer temperatures vary from 26 to 14 °C, while below the thermocline, temperatures remain below 14 °C (Jamshidi, 2017).

Thus, Cyprideis, adapted to different depths, was larger in the colder sublittoral environment and smaller in the warmer littoral zone, in accordance with Bergmann's rule (Atkinson and Sibly, 1997; Angilletta et al., 2004).

Lake Pannon, a long-lived lake, provides an opportunity to test models of ecologically driven speciation. Morphometric analysis of valve outlines, combined with measurable taxonomic parameters of the hinge, can yield sufficient data on species radiation.

During the Middle Miocene, the polymorphic paleopopulations of Cyprideis pannonica occurred in the lacustrine-brackish to brachyhaline estuary facies of the late Sarmatian Sea. The studied paleopopulations exhibit a relatively high statistical separation (R=0.6) but share an identical hinge composition. The paleogeographical shift between the Middle and Late Miocene led to the formation of a brackish lake, which C. pannonica subsequently colonized. Although the early Pannonian period facilitated speciation, it was too brief (approximately 500 ka), and the lake was ecologically unstable for significant morphometric diversification.

The re-flooding of the basin in the middle Pannonian was associated with greater ecological heterogeneity and lasted approximately 1 million years. This event strongly influenced water depth segregation, ultimately leading to the high morphometric variability of Cyprideis, hinge differentiation, and species diversity. Thus, the multiphase tectonic history of the Central Paratethys played a major role in the diversification of the endemic ostracod fauna of Lake Pannon.

The datasets of the TPS files of all specimens supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Mendeley data repository, under the title “TPS files for calculating shape outline differences in Lake Pannon Cyprideis (Ostracoda)”. Hyperlink to datasets: https://doi.org/10.17632/nvs5xhcr63.2 (Pipík and Gross, 2025).

The material originates from the Vienna, Danube, and Styrian basins (Fig. 1). All examined specimens, along with their digital images, are stored in the personal collection of Radovan Pipík at the ESI SAS in Banská Bystrica, Slovakia. C. mataschensis and C. kapfensteinensis are housed in the collection of the Universalmuseum Joanneum in Graz, Austria.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-45-33-2026-supplement.

RP: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, and writing (original draft, review, editing, and visualization). MG: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing (review and visualization). DS: formal analysis, investigation, resources, and writing (review, editing, and visualization).

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We are grateful that Dan L. Danielopol (Austria), Mathias Harzhauser (Austria), and Imre Magyar (Hungary) shared their knowledge on Ostracoda and outcrops in the Vienna and Danube basins. Special thanks go to Alžbeta Svitáčová (Slovakia), Klaus Minati (Austria), and Josef Knoblechner (Austria) for their technical help. We also thank the reviewers for their constructive comments.

This work was supported by the VEGA project (project no. 2/0085/24) and the European-Union-funded Integrated Infrastructure Initiative grant SYNTHESIS (project nos. GB-TAF-4361 and BE-TAF-4362). Radovan Pipík also benefited from the scientific exchange programme between the Slovak Academy of Sciences and the Austrian Academy of Sciences. This work was funded in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (grant DOI: https://doi.org/10.55776/P21748).

This paper was edited by Francesca Sangiorgi and Moriaki Yasuhara and reviewed by Elsa Gliozzi and Emőke Mohr.

Akgün, F., Kayseri, M. S., and Akkiraz, M. S.: Palaeoclimatic evolution and vegetational changes during the Late Oligocene–Miocene period in Western and Central Anatolia (Turkey), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 253, 56–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.03.034, 2007.

Aladin, N. V. and Potts, W. T. W.: The osmoregulatory capacity of the Ostracoda, J. Comp. Physiol. B, 166, 215–222, 1996.

Altizer, S., Harvell, D., and Friedle, E.: Rapid evolutionary dynamics and disease threats to biodiversity, Trends Ecol. Evol., 18, 589–596, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2003.08.013, 2003.

Angilletta, M. J. Steury, T. D., and Sears, M. W.: Temperature, growth rate, and body size in ectotherms: fitting pieces of a life-history puzzle, Integr. Comp. Biol., 44, 498–509, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.498, 2004.

Atkinson, D. and Sibly, R. M.: Why are organisms usually bigger in colder environments? Making sense of a life history puzzle, Trends Ecol. Evol., 12, 235–239, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01058-6, 1997.

Balázs, A., Magyar, I., Matenco, L., Sztanó, O., Tőkés, L., and Horváth, F.: Morphology of a large paleo-lake: Analysis of compaction in the Miocene-Quaternary Pannonian Basin, Glob. Planet. Change, 171, 134–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2017.10.012, 2018.

Bassiouni, M. E. A. A.: Brackische und marine Ostrakoden (Cytherideinae, Hemicytherinae, Trachyleberidinae) aus dem Oligozän und Neogen der Türkei (Känozoikum und Braunkohlen der Türkei), Geol. Jahrb., Reihe B (Reg. Geol. Ausl.), 31, 3–195, 1979.

Bodergat, A.-M.: Les ostracodes, témoins de leurs environnement: approche chimique et écologie en milieu lagunaire et océanique, Doc. lab. géol. Lyon, 88, 1–246, 1983.

Bodergat, A.-M.: Composition chimique des carapaces d'Ostracodes, Paramètres du milieu de vie, in: Atlas des ostracodes de France (Paléozoique-Actuel), edited by: Oertli, H. J., B. Cent. Rech. Expl., 9, 379–386, 1985.

Boomer, I.: Ostracoda as indicator of climatic and human-influenced changes in the late Quaternary of the Ponto-Caspian Region (Aral, Caspian and Black Seas). Dev. Quat. Sci., 17, 205–215, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53636-5.00012-3, 2012.

Boomer, I., Frenzel, P., and Feike, M.: Salinity-driven size variability in Cyprideis torosa (Ostracoda, Crustacea), J. Micropaleontol., 36, 63–69, https://doi.org/10.1144/jmpaleo2015-043, 2017.

Brauneis, W., Linhart, J., Stracke, A., Danielopol, D. L., Neubauer, W., and Baltanás. A.: Morphomatica (Version 1.6) User Manual/Tutorial, Mondsee, 2006a.

Brauneis, W., Neubauer, W., Linhart, J., and Danielopol, D. L.: Morphomatica approximation of Ostracoda, Computer Programme version 1.6, 2006b.

Cernajsek, T.: Die Ostracodenfaunen der Sarmatischen Schichten in Österreich, in: Chronostratigraphie und Neostratotypen, Miozän der Zentralen Paratethys, Bd. IV, M5, Sarmatien, edited by: Brestenská, E., VEDA, Bratislava, 458–491, 1974.

Clarke, K. R. and Gorley, R. N.: Primer v5: User manual/tutorial, PRIMER-E Ltd, Plymouth, 2001.

Clarke, K. R. and Gorley, R. N.: Primer v6. Computer programme and user manual/tutorial, PRIMER-E Ltd, Plymouth, 2006.

Cohen, A.S.: Extinction in ancient lakes: Biodiversity crises and conservation 40 years after J.L. Brooks, in: Speciation in ancient lakes, edited by: Martens, K., Goddeeris, B., and Coulter, G., Arch. Hydrobiol., Beih. Advan. Limnol., 44, 451–179, 1994.

Cohen, A. S. and Johnston, M. R.: Speciation in brooding and poorly dispersing lacustrine organisms. Palaios, 2, 426–435, https://doi.org/10.2307/3514614, 1987.

Colin, J. P. and Danielopol, D. L.: Why most of the Timiriaseviinae (Ostracoda, Crustacea) became extinct, Geobios, 12, 745–749, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-6995(79)80102-3, 1979.

Cronin, T. M.: Speciation and stasis in marine Ostracoda: climatic modulation of evolution, Science, 277, 60–63, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.227.4682.60, 1985.

Cziczer, I., Magyar, I., Pipík, R., Böhme, M., Ćorić, S., Bakrač, K., Sütő-Szentai, M., Lantos, M., Babinszki, E., and Müller, P.: Life in the sublittoral zone of Lake Pannon: paleontological analysis of the Upper Miocene Szák Formation, Hungary, Int. J. Earth Sci., 98, 1741–1766, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-008-0322-3, 2009.

De Deckker, P. and Lord, A.: Cyprideis torosa: a model organism for the Ostracoda?, J. Micropalaeontol., 36, 3–6, https://doi.org/10.1144/jmpaleo2016-100, 2017.

Duveillera, G., Caporaso, L., Abad-Viñas, R., Perugini, L., Grassi, G., Arneth, A., and Cescatti, A.: Local biophysical effects of land use and land cover change: towards an assessment tool for policy makers, Land Use Policy, 91, 104382, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104382, 2020.

Feniova, I. Y., Palash, A. L., Razlutskij, V. I., and Dzialowski, A. R.: Effects of temperature and resource abundance on small- and large-bodied cladocerans: Community stability and species replacement, Open J. Ecol., 3, 164–171, https://doi.org/10.4236/oje.2013.32020, 2013.

Fordinál, K. and Zlínska, A.: Fauna vrchnej časti holíčskeho súvrstvia (sarmat) v Skalici (viedenská panva) (Fauna of the upper part of the Holíč Formation (Sarmatian) in Skalica (Vienna Basin)), Min. Slovaca, 30, 137–146, 1998.

Frenzel, P.: Die Ostracodenfauna der tiefen Teile der Ostsee-Boddengewässer Vorpommerns. Meyniana, 43, 151–175, 1991.

Gamenick, I., Jahn, A., Vopel, K., and Giere, O.: Hypoxia and sulphide as structuring factors in a macrozoobenthic community on the Baltic Sea shore: colonization studies and tolerance experiments, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 144, 73–85, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps144073, 1996.

Geary, D. H.: Patterns of evolutionary tempo and mode in the radiation of Melanopsis (Gastropoda; Melanopsidae), Paleobiology, 16, 492–511, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0094837300010216, 1990.

Geary, D. H., Rich, J. A., Valey, J. W., and Baker, K.: Stable isotopic evidence of salinity change: Influence on the evolution of melanopsid gastropods in the late Miocene Pannonian basin. Geology, 17, 981–985, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1989)017<0981:SIEOSC>2.3.CO;2, 1989.

Geary, D. H., Staley, A. W., Müller, P., and Magyar, I.: Iterative changes in Lake Pannon Melanopsis reflect a recurrent theme in gastropod morphological evolution, Paleobiology, 28, 208–221, https://doi.org/10.1666/0094-8373(2002)028<0208:ICILPM>2.0.CO;2, 2002.

Geary, D. H., Hunt, G., Magyar, I., and Schreiber, H.: The paradox of gradualism: phyletic evolution in two lineages of lymnocardiid bivalves (Lake Pannon, central Europe), Paleobiology, 36, 592–614, https://doi.org/10.1666/08065.1, 2010.

Gitter, F., Gross, M., and Piller, W. E.: Sub-Decadal resolution in sediments of Late Miocene Lake Pannon reveals speciation of Cyprideis (Crustacea, Ostracoda), PLoS One, 10, e0109360, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109360, 2015.

Gliozzi, E., Rodriguez-Lazaro, J., and Pipík, R.: The Neogene Mediterranean origin of Cyprideis torosa (Jones, 1850), J. Micropalaeontol., 36, 80–93, https://doi.org/10.1144/jmpaleo2016-029, 2017.

Gross, M. and Piller, W. E.: Saline waters in Miocene Western Amazonia – an alternative view, Front. Sci., 8, 116, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.00116, 2020.

Gross, M., Minati, K., Danielopol, D. L., and Piller, W. E.: Environmental changes and diversification of Cyprideis in the Late Miocene of the Styrian Basin (Lake Pannon, Austria), Senckenb Lethaea, 88, 161–181, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03043987, 2008.

Gross, M., Piller, W. E., Schalger, R., and Gitter, F.: Biotic and abiotic response to palaeoenvironmental changes at Lake Pannons' western margin (Central Europe, Late Miocene), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 312, 181–193, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.10.010, 2011.

Gross, M., Ramos, M. I., Caporaletti, M., and Piller, W. E.: Ostracods (Crustacea) and their palaeoenvironmental implication for the Solimões Formation (Late Miocene; Western Amazonia/Brazil), J. South Am. Earth Sci., 42, 216–241, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2012.10.002, 2013.

Gross, M., Ramos, M. I. F., and Piller, W. E.: On the Miocene Cyprideis species flock (Ostracoda; Crustacea) of Western Amazonia (Solimões Formation): refining taxonomy on species level, Zootaxa, 3899, 1–69, https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3899.1.1, 2014.

Harzhauser, M. and Piller, W. E.: The Early Sarmatian – hidden seesaw changes, Cour. Forsch. Senck., 246, 89–112, 2004a.

Harzhauser, M. and Piller, W. E.: Integrated Stratigraphy of the Sarmatian (Upper Middle Miocene) in the western Central Paratethys, Stratigraphy, 1, 65–86, 2004b.

Harzhauser, M. and Piller, W. E.: Benchmark data of a changing sea – Palaeogeography, Palaeobiogeography and events in the Central Paratethys during the Miocene, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 253, 8–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.03.031, 2007.

Harzhauser, M. and Tempfer, P. M.: Late Pannonian Wetland Ecology of the Vienna Basin based on Molluscs and Lower Vertebrate Assemblages (Late Miocene, MN 9, Austria), Cour. Forsch. Senck., 246, 55–68, 2004.

Harzhauser, M., Kowalke, T., and Mandic, O.: Late Miocene (Pannonian) Gastropods of Lake Pannon with Special Emphasis on Early Ontogenetic Development, Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien, 103A, 75–141, 2002.

Harzhauser, M., Kovar-Eder, J., Nehyba, S., Ströbitzer-Hermann, M., Schwarz, J., Wójcicki, J., and Zorn, I.: An Early Pannonian (Late Miocene) Transgression in the Northern Vienna Basin – The Paleoecological Feedback, Geol. Carpath., 54, 41–52, 2003.

Harzhauser, M., Daxner-Höck, G., and Piller, W. E.: An integrated stratigraphy of the Pannonian (Late Miocene) in the Vienna Basin, Aust. J. Earth Sci., 95/96, 6–19, 2004.

Harzhauser, M., Kern, A., Soliman, A., Minati, K., Piller, W. E., Danielopol, D. L., and Zuschin. M.: Centennialto decadal scale environmental shifts in and around Lake Pannon (Vienna Basin) related to a major Late Miocene lake level rise, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 270, 102–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.09.003, 2009.

Harzhauser, M., Latal, C., and Piller, W. E.: The stable isotope archive of Lake Pannon as a mirror of Late Miocene climate change, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 249, 335–350, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.02.006, 2007.

Harzhauser, M., Peresson, M., Benold, C., Mandic, O., Coric, S., and De Lange G. J.: Environmental shifts in and around Lake Pannon during the Tortonian Thermal Maximum based on a multi-proxy record from the Vienna Basin (Austria, Late Miocene, Tortonian), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 610, 111332, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.111332, 2023.

Heip, C.: The Life-Cycle of Cyprideis torosa (Crustacea, Ostracoda), Oecologia, 24, 229–245, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00345475, 1976.

Jamshidi, S.: Assessment of thermal stratification, stability and characteristics of deep water zone of the southern Caspian Sea, J. Ocean Eng. Sci., 2, 203–216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joes.2017.08.005, 2017.

Jiménez-Moreno, G.: Progressive substitution of a subtropical forest for a temperate one during the middle Miocene climate cooling in Central Europe according to palynological data from cores Tengelic-2 and Hidas-53 (Pannonian Basin, Hungary), Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol., 142, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2006.05.004, 2006.

Jones, T. R.: Description of the Entomostraca of the Pleistocene beds of Newbury, Copford, Clacton, and Grays, Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist., London, series 2, 25–28, 1850.

Jiříček, R.: Die Ostracoden des Pannonien, in: Chronostratigraphie und Neostratotypen, Miozän der Zentral Paratethys, Bd. VII, M6 Pannonien (Slavonien und Serbien), edited by: Papp, A., Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 378–425, ISBN 963053942X, 1985.

Kadolsky, D.: Mollusks from the Oligocene of Oberleichtersbach (Rhön Mountains, Germany). Part 1: Overview and preliminary biostratigraphical, palaeoecological and palaeogeographical conclusions, Cour. Forsch. Senck., 260, 89–101, 2008.

Kilenyi, T. I.: Transient and balanced genetic polymorphism as an explanation of variable nodding in the ostracode Cyprideis torosa, Micropaleontol., 18, 47–63, 1972.

Kollmann, K.: Cytherideinae und Schulerideinae n. subffam. (Ostracoda) aus dem Neogen des östl. Oesterreich, Mitt. Geol. Ges. Wien, 51, 89–195, 1960.

Kováč, M., Baráth, I., Kováčová-Slamková, M., Pipík, R., Hlavatý, I., and Hudáčková, N.: Late Miocene paleoenvironments and sequence stratigraphy: northern Vienna Basin, Geol. Carpath., 49, 445–458, 1998.

Krstić, N.: Ostracoden im Pannonien der Umgebung von Belgrad, in: Chronostratigraphie und Neostratotypen, Miozän der Zentral Paratethys, Bd. VII, M6 Pannonien (Slavonien und Serbien), edited by: Papp, A., Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 103–143, ISBN 963053942X, 1985.

Ligios, S. and Gliozzi, E.: The genus Cyprideis Jones, 1857 (Crustacea, Ostracoda) in the Neogene of Italy: a geometric morphometric approach, Rev. Micropaleontol., 55, 171–207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmic.2012.09.002, 2012.

Lin, Z., Strauss, H., Peckmann, J., Roberts, A.P., Lu, Y., Sun, X., Chen, T., and Harzhauser, M.: Seawater sulphate heritage governed early Late Miocene methane consumption in the long-lived Lake Pannon, Commun. Earth Environ., 4, 207, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00879-2, 2023.

Magyar, I., Geary, D. H., and Müller, P.: Paleogeographic evolution of the Late Miocene Lake Pannon in Central Europe, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 147, 151–167, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00155-2, 1999.

Magyar, I., Lantos, M., Ujszaszi, K., and Kordos, L.: Magnetostratigraphic, seismic and biostratigraphic correlations of the Upper Miocene sediments in the northwestern Pannonian Basin System, Geol. Carpath., 58, 277–290, https://doi.org/10.2478/v10096-011-0021-z, 2007.

Magyar, I., Botka, D., Katona, L., Harangi, S., Lukács, R., and Šujan, M.: The Pannonian Stage: stratigraphy and geoenergy source, in: The Miocene Extensional Pannonian Superbasin, Vol. 1: Regional Geology, edited by: Tari, G. C., Kitchka, A., Krézsek, C., Markič, M., Radivojevič, D., Sachsenhofer, R. F., and Šujan, M., Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ., 554, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP554-2024-60, 2025.

Malz, H. and Triebel, E.: Ostracoden aus dem Sannois und jüngeren Schichten des Mainzer Beckens. 2: Hemicyprideis n. g. Senckenb. Lethaea, 51, 1–47, 1970.

Martens, K.: Ostracod speciation in ancient lakes: a review, in: Speciation in ancient lakes, edited by: Martens, K., Goddeeris, B., and Coulter, G., Arch. Hydrobiol., Beih. Advan. Limnol., 44, 203–222, 1994.

Martens, K., Coulter, G., and Goddeeris, B.: Speciation in Ancient lakes – 40 years after Brooks, in: Speciation in ancient lakes, edited by: Martens, K., Goddeeris, B., and Coulter, G., Arch. Hydrobiol., Beih. Advan. Limnol., 44, 75–96, 1994.

Mátyás, J., Burns, S. J, Müller, P., and Magyar, I.: What can stable isotopes say about salinity? An example from the Late Miocene Pannonian Lake, Palaios, 11, 31–39, https://doi.org/10.2307/3515114, 1996.

Meisch, C.: Freshwater Ostracoda of Western and Central Europe, Heidelberg – Berlin: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, 522 pp., ISBN 3-8274-1001-0, 2000.

Minati, K., Cabral, M. C., R. Pipík, D. L. Danielopol, Linhart, J., and Neubauer, W.: Morphological variability among European populations of Vestalenula cylindrica (Straub) (Crustacea, Ostracoda), Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 264, 296–305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.027, 2008.

Müller, P., Geary, D. H., and Magyar, I.: The endemic mollusks of the Late Miocene Lake Pannon: their origin, evolution, and family-level taxonomy. Lethaia, 32, 47–60, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00580.x, 1999.

Neubauer, T. A., Harzhauser, M., Mandic, O., Kroh, A., and Georgopoulou, E.: Evolution, turnovers and spatial variation of the gastropod fauna of the late Miocene biodiversity hotspot Lake Pannon, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 442, 84–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.11.016, 2016.

Papp, A.: Das Pannon des Wiener Beckens, Mitt. Geol. Ges. Wien 1946, 39–41 and 1948, 99–193, 1951.

Park, L. E. and Martens, K.: Four new species of Gomphocythere (Crustacea, Ostracoda) from Lake Tanganyika, East Africa, Hydrobiologia, 450, 129–147, 2001.

Plisnier, P.-D., Chitamwebwa, D., Mwape, L., Tshibangu, K., Langenberg, V., and Coenen, E.: Limnological annual cycle inferred from physical-chemical fluctuations at three stations of Lake Tanganyika, Hydrobiologia, 407, 45–58, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017528407191, 1999.

Pint, A. and Frenzel, P.: Ostracod fauna associated with Cyprideis torosa – an overview, J. Micropalaeontol., 36, 113–119, https://doi.org/10.1144/jmpaleo2016-010, 2017.

Pipík, R.: Salinity changes recorded by ostracoda assemblages found in Pannonian sediments in the western margin of the Danube Basin, B. Cent. Rech. Expl., 20, 167–177, 1998.

Pipík, R.: Phylogeny, palaeoecology, and invasion of non-marine waters by the late Miocene hemicytherid ostracod Tyrrhenocythere from Lake Pannon, Acta Palaeontol. Pol., 52, 351–368, 2007.

Pipik, R. and Gross, M.: TPS files for calculating shape outline differences in Lake Pannon Cyprideis (Ostracoda), V2, Mendeley Data [data set], https://doi.org/10.17632/nvs5xhcr63.2, 2025.

Pipík, R., Fordinál, K., Slamková, M., Starek, D., and Chalupová, B.: Annotated checklist of the Pannonian microflora, evertebrate and vertebrate community from Studienka, Vienna Basin. Scripta Fac. Sci. Nat. Univ. Masaryk. Brunensis, Geology, 31–32, 47–54, 2004.

Pipík, R., Fordinál, K., and Starek, D.: Late Miocene freshwater ostracoda in the Lake Pannon, in: 3rd International Workshop Neogene of Central and South-Eastern Europe, edited by: Filipescu, S., Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 81–82, ISBN 978-973-610-873-0, 2009.

Pokorný, V.: The ostracods of the so-called Basal Horizon of the Subglobosa Beds at Hodonín (Pliocene, Inner Alpine Basin, Czechoslovakia), Sbor. Ústř. Ústavu geol., 19, 229–396 pp., 1952.

Rausch, L., Stoica, M., and Lazarev, S.: A Late Miocene – Early Piocene Paratethyan type ostracod fauna from the Denizli Basin (SW Anatolia) and its palaeogeographic implications, Acta Palaeontol. Roman., 16, 2, 3–56, https://doi.org/10.35463/j.apr.2020.02.01, 2020.

Regan, J. L., Meffert, L. M., and Bryant, E. H.: A direct experimental test of founder-flush effect on the evolutionary potential for assortative mating, J. Evol. Biol., 16, 302–312, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00521.x, 2003.

Rohlf, F. J.: TPS-dig, Computer Programme version 1.4. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 2004.

Schluter, D.: Ecological causes of adaptive radiation, Am. Nat., 148 (Supplement), S40–S64, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2463047 (last access: 25 November 2025), 1996.

Schön, I. and Martens, K.: Adaptive, pre-adaptive and non-adaptive components of radiations in ancient lakes: a review, Org. Divers. Evol., 4, 137–156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ode.2004.03.001, 2004

Schön, I. and Martens, K.: Molecular analyses of ostracod flocks from Lake Baikal and Lake Tanganyika, Hydrobiologia, 682, 91–110, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-011-0935-6, 2012.

Sheldon, P. R.: Plus ça change – a model for stasis and evolution in different environments, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 127, 209–227, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(96)00096-X, 1996.

Smith, A. J. and Horne, D. J.: Ecology of marine, marginal marine and nonmarine ostracodes, in: The Ostracoda: Application in Quaternary Research, edited by: Holmes, J. A. and Chivas, A. R., Geophys. Monogr. Ser., American Geophysical Union, Washington D.C., 37–64, https://doi.org/10.1029/131GM03, 2002.

Sokać, A.: Pannonian and Pontian ostracode fauna of Mt. Medvednica, Palaeontologia Jugoslavica, 11, 9–140, 1972.

Starek, D., Pipík, R., and Hagarová, I.: Meiofauna, trace metals, TOC, sedimentology and oxygen availability in the Upper Miocene sublittoral deposits of the Lake Pannon, Facies, 56, 369–384, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-009-0208-2, 2010.

Šujan, M., Braucher, R., Mandič, O., Fordinál, K., Brixová, B., Pipík, R., Šimo, V., Jamrich, M., Rybár, S., Klučiar, T., Aster Team, Ruman, A., Zvara, I., and Kováč, M.: Lake Pannon transgression on the westernmost tip of the Carpathians constrained by biostratigraphy and authigenic dating (Central Europe), Riv. Ital. Paleontol. S., 127, 627–653, https://doi.org/10.13130/2039-4942/16620, 2021.

Tkach, A.A.: Recent near-shore ostracod fauna of the Caspian Sea, Limnol. Freshw. Biol., 3, 142–156, https://doi.org/10.31951/2658-3518-2024-A-3-142, 2024.

Tuzhilkin, V. S. and Kosarev, A. N.: Thermohaline structure and general circulation of the Caspian Sea waters, Environ. Chem., 5P, 35–57, https://doi.org/10.1007/698_5_003, 2005.

Van Harten, D.: Size and environmental salinity in the modern euryhaline ostracod Cyprideis torosa (Jones, 1850), a biometrical study, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 17, 35–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(75)90028-0, 1975.

Van Harten, D.: The Neogene evolutionary radiation in Cyprideis Jones (Ostracoda: Cytheracea) in the Mediterranean Area and the Paratethys, Cour. Forsch. Senck., 123, 191–198, 1990.

Van Harten, D.: Variable nodding in Cyprideis torosa (Ostracoda, Crustacea): an overview, experimental results and a model from Catastrophe Theory, in: Evolutionary Biology and Ecology of Ostracoda, edited by: Horne, D. J. and Martens, K., Hydrobiologia, 419, 131–139, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003935419364, 2000.

Van Morkhoven, F. P. C. M.: Post-paleozoic Ostracoda, Their Morphology, Taxonomy, and Economic Use, Volume I. Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam-London-New York, 224 pp., 1962.

Von Rintelen, T., Wilson, A. B., Meyer, A., and Glaubrecht, M.: Escalation and trophic specialization of freshwater gastropods in ancient lakes on Sulawesi, Indonesia, Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B, 271, 2541–2549, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.2842, 2004.

Whatley, R. C., Muñoz-Torres, F., and Van Harten, D.: The Ostracoda of an isolated Neogene saline lake in the Western Amazon basin, B. Cent. Rech. Expl., 20, 231–245, 1998.

Wouters, K.: On the distribution of Cyprideis torosa (Jones) (Crustacea, Ostracoda) in Africa, with the discussion of a new record from the Seychelles, Bull. Inst. R. Sci. Nat. Belg., 72, 31–140, 2002.

Wouters, K.: On the modern distribution of the euryhaline species Cyprideis torosa (Jones, 1850) (Crustacea, Ostracoda), J. Micropalaeontol., 36, 21–30, https://doi.org/10.1144/jmpaleo2015-021, 2017, 2017.

Wouters, K. and Martens, K.: On the Cyprideis species flock (Crustacea, Ostracoda) in Lake Tanganyika, with the description of four new species, Hydrobiologia, 450, 111–127, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017547523121, 2001.